Constipation is frequent complaint in patients attending general practitioners and gastroenterologists. Recently, there have been advances related to pathophysiology, which has made possible to develop new drugs that are now available for the treatment of chronic constipation (CC). These drugs target several mechanisms of action including stool wetting, smooth muscle stimulants and receptor-specific mechanism action such as the chloride channel receptors activators, guanylate cyclase receptor activators, opioid receptor antagonist and 5HT4 receptor agonist. In this review, we will focus on treatment of functional constipation by discussing mechanism of action and current indications for each of the available drugs.

El estreñimiento es una queja común en pacientes que son atendidos por los médicos generales y los gastroenterólogos. Recientemente ha habido avances relacionados a la fisiopatología, lo que ha hecho posible desarrollar nuevos medicamentos que ya están disponibles para el tratamiento del estreñimiento crónico. Estos medicamentos se enfocan en diferentes mecanismos de acción, incluyendo ablandadores de heces, estimulantes del músculo liso y receptores específicos de mecanismo de acción, tales como los activadores de los receptores del canal de cloro, activadores de los receptores de la guanilil ciclasa, antagonistas de los receptores de los opioides y los agonistas del receptor 5HT4. En esta revisión nos enfocaremos en el tratamiento del estreñimiento funcional, discutiendo los mecanismos de acción y las actuales indicaciones para cada uno de los medicamentos disponibles.

Introduction

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal disorder. In North America, estimates of its prevalence are between 2-19%.1 Similar trends are reported in Latin-America with prevalences around 5-21%.2 Constipated patients consume more health resources that include prescription and OTC laxatives and other alternative treatments. Also, constipation leads to impaired quality of life.3,4

Constipation is difficult to assess, mainly because of the heterogeneity or patient's symptoms, their perceptions or their ability to communicate them to their physician, but sometimes, the problem is a misinterpretation of their symptoms by the physician. Frequently, constipation is associated with a list of symptoms including infrequent passage of stools, hard or lumpy stools, increase in straining and sense of incomplete evacuation.5 Therefore, understanding constipation-related symptoms in a particular individual is a crucial step before starting any treatment and this is important as excluding organic diseases, metabolic disturbances and drug-related adverse effects as secondary causes of constipation.

Constipation has been classified into three pathophysiologic groups: 1) Normal transit constipation (50%), frequently is a result of environmental, genetic and socio-psychological or dietary factors. Example of this include chronic functional constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation-predominant. 2) Dyssynergic defecation (30%), due to incoordination between abdominal and pelvic muscle contraction, requiring both medical and biofeedback management and 3) slow transit constipation (20%), often a result of colonic myopathy or neuropathy, frequently requiring an aggressive medical treatment and when they fail, a surgical intervention may be required. It is important to recognize that more than one mechanism may be present in a single patient and frequently there is an overlap between these subtypes.6,7

Treatment of constipation should be individualized since success is related to addressing the underlying cause. Acknowledging patient's comorbid conditions, patient's concerns and expectations which are often driven by life style, are important at the time of considering a treatment option. The focus of the present article is to discuss management options for chronic constipation (CC), with particular emphasis on newer treatments and future directions.

Current treatment options for chronic constipation

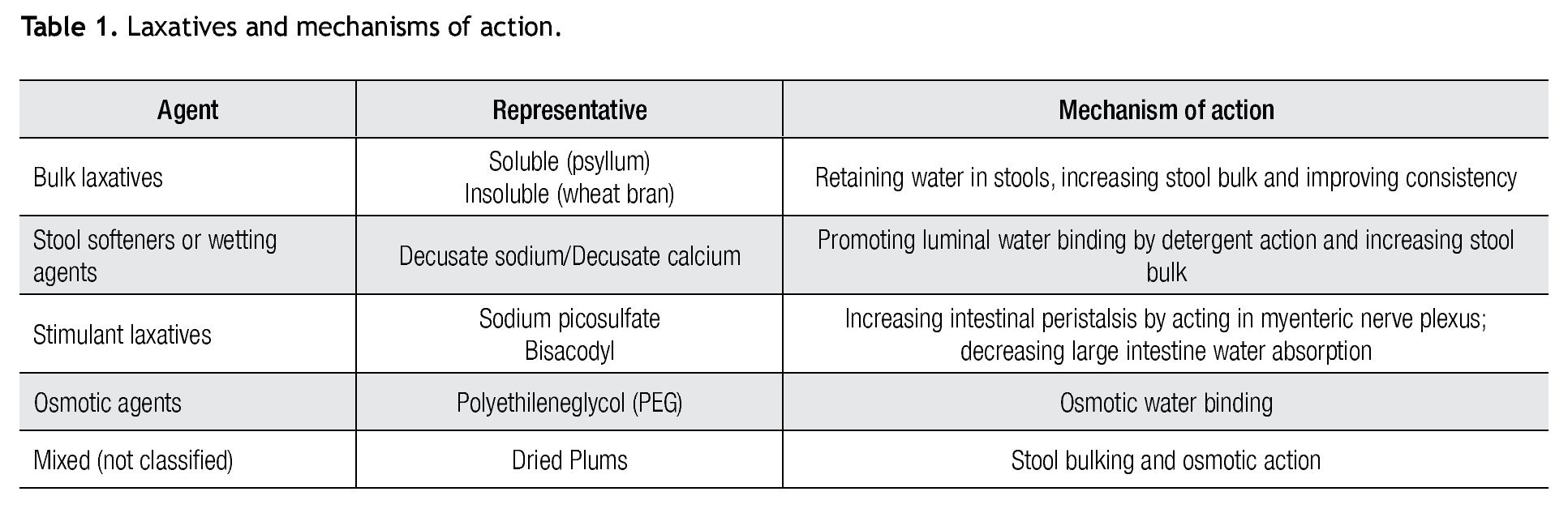

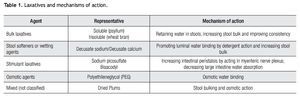

There are several therapeutic interventions in CC. However, there is scarce evidence related the most popular over-the-counter laxative therapies8-11 (Table 1).

Bulk laxatives (fiber)

Fiber has been proposed as first line therapeutic intervention in CC and several gastroenterological organizations have supported this recommendation.12,13 Fiber can be supplemented in two forms: soluble (psyllium) and insoluble (wheat bran). There is no consensus about what class of fiber should be considered as first choice. Some patients are intolerant to some fibers (wheat hypersensitivity) whereas others dislike either consistency and/ or taste of some compounds. It is recommended to start this in small amounts and increase in a step-wise manner to prevent side effects. Whether a particular fiber is tolerated or not, will be essential for deciding maintenance therapy. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that soluble fiber may be beneficial but outcomes regarding insoluble fiber offer conflicting results.14 Other bulk laxatives include calcium, policarbophil and methilcellulose. Table 1 represents a summary of efficacy, mechanism of action and side effects for this class of laxatives.

Stool softeners or wetting agents

These work as surfactants, because of their detergent properties, promote water interaction more effectively with solid stools, thereby leading to stools softening. These include dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate/docusate sodium and docusate calcium. Efficacy and side effects are summarized in Table 1.

Stimulant laxatives

These are pro-drugs, which once in the gut, are converted to their active metabolite bis-(p-hydroxyphenyl)-pyridyl-2-methane, promoting the desired laxative effect, mainly by stimulating myenteric plexus on contact with colonic mucosa and also by inhibiting water absorption. Examples of these agents are bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate. There are limited data supporting their use. A four week trial with sodium picosulfate showed an increase in the number of complete spontaneous bowel movements compared with placebo (0.9 ± 0.1 to 3.4 ± 0.2; placebo: 1.1 ± 0.1 to 1.7 ± 0.1; p<0.0001).15 Another recent trial using bisacodyl, showed similar results with an increase in complete spontaneous bowel movement from 1.1 (CSBM) to 5.2 ± 0.3 in the bisacodyl group and 1.9 ± 0.3 in the placebo group (p<0.0001). Secondary endpoints for both studies were also significant, showing improvement of constipation related symptoms and quality of life.16

Senna derivatives are also stimulants that are widely available even as an OTC medication. There are not randomized controlled studies with senna derivatives and just some comparative studies with other laxatives. Senna derivatives appear to be a good choice for treatment of CC,17 being even more effective when provided with other laxatives (i.e, psyllium, lactulose).18,19 Although there are concerns about safety profile of senna derivatives regarding the development of cathartic colon, toxicity (melanosis coli) and carcinogenesis but until now, there is no evidence to support these concerns.20

Stimulant laxatives have been used as rescue therapy; because they may induce tolerance that leads to an increased dose. Because of this and potential for melanosis coli, some authors have raised concerns about long-term safety of these laxatives. So far, they are considered safe and effective for short duration treatment as well as for rescue therapy.

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives are large molecules that create an osmotic gradient within the intestinal lumen drawing fluid into the intestinal lumen and promoting stool softening and thereby promoting stool propulsion. Polyethyleneglycol (PEG) is a non-absorbable and non-metabolizable agent. In several placebo-controlled trials, PEG showed an increase in stool frequency and diminished stool consistency.9 It has been shown that PEG is more effective and safe when compared to tegaserod.21 PEG also appears to be safe and effective in the treatment of older adults with constipation for a period of up to 12 months.22 Common adverse events are diarrhea, nausea, bloating, cramping and flatulence. Electrolyte imbalance may occur especially and patients with advanced renal disease and in older adults. This particular situation requires a careful dose titration and careful monitoring on this patient population. PEG seems to be more cost-effective than lactulose, as suggested by a study of decision to treat.23 Magnesium salts (magnesium hydroxide and magnesium citrate and sulfate) are also osmotic agents. Extra caution is necessary using when using these salts, especially in patients with impaired renal function.

Dried plums and prune juice have been compared with Psyllium (6 g of fibre at day) in a single-blind randomized, crossover study including 40 patients. CSBM and stool consistency improved significantly with dried plums compared to psyllium. Furthermore, dried plums were rated as being tastier and better tolerated related to psyllium.24

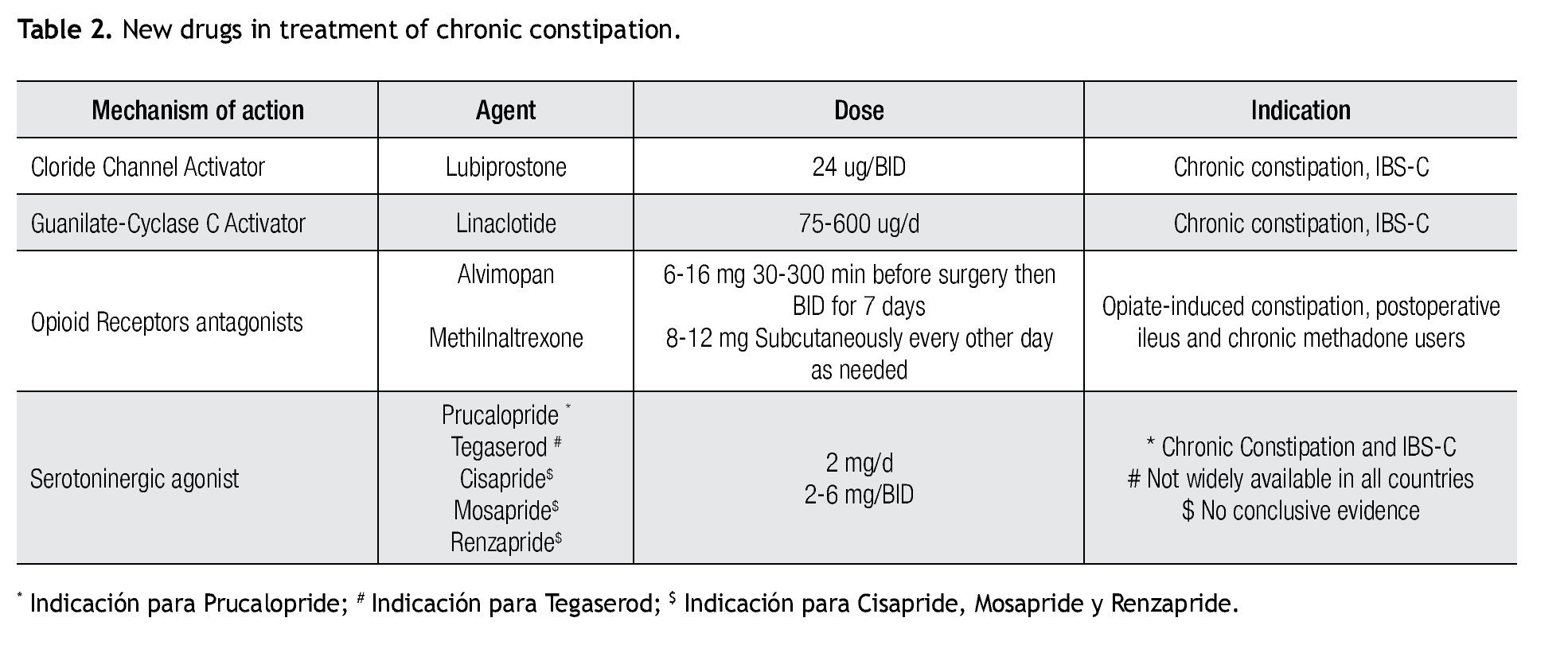

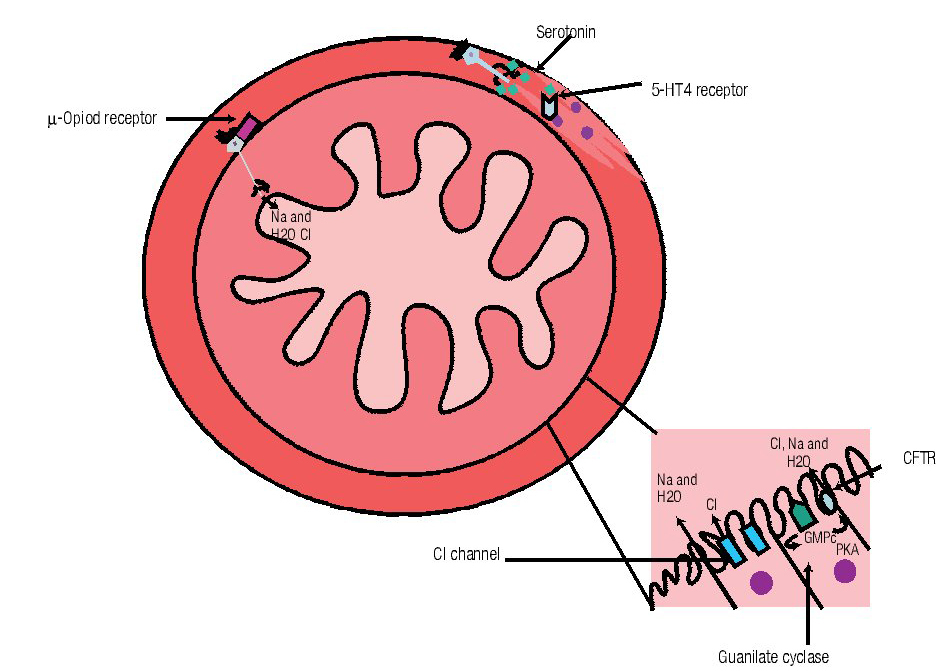

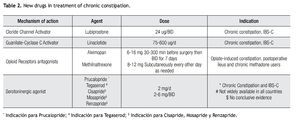

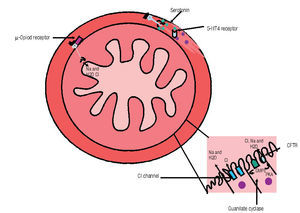

Although all previously mentioned agents are considered first-line treatment choices, recently, newer therapies for constipation are becoming available for the treatment of CC (Table 2). Different classes of medications and their mechanisms of action are described in Figure 1.

Figura 1. Mechanism of action of different drugs for the treatment of constipation. A) Opioids receptor antagonist acts at µ receptors widespread distributed along the gut. B) Serotonin (5HT4) agonists are located in the muscular layer and C) Linaclotide (Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, CFTR) and lubiprostone (Chloride channel, Cl channel) mechanism of action is located at the brush border in the intestinal epithelium. (GMP= Guanilil monophosphate, PKA = protein-kinase A)

Chloride channel activators

Chloride channels are widely distributed throughout the body. These chloride channels are composed of trans-membrane porous proteins that play a key role in maintaining homeostasis of fluid transport through cell membranes.25

Lubiprostone, selectively activates Chloride channel 2 (ClC2) via protein kinase-A as well as through activation the cystic-fibrosis transmembrane conductance receptor (CFTR),26,27 both mechanisms promote intestinal fluid secretion. Lubiprostone secondarily induces peristalsis by promoting fluid secretion and bowel distention but without a direct effect on intestinal smooth muscle. Onset of action is fast and half-life is around three hours.25 Lubiprostone is poorly absorbed. It is metabolized mainly in the stomach and jejunum where it is transformed through microsomal carbonyl-transferases into M3, which is its active metabolite.

Lubiprostone acts in a dose-dependent manner, although most trials have used 24 ug twice daily.28,29 A Japanese study showed that lubiprostone 48 ug/day, induces an increase in the number of spontaneous bowel movement (SBM) compared to 16 and 32 ug/day in patients with or without iBS.30 Additionally, three open label trials have demonstrated an increase in SBM, a decrease in straining and improved stool consistency, leading to a greater global symptomatic improvement and patient satisfaction.31

Common adverse events are nausea (31%), diarrhea (12%) and headache (11%). Abdominal distention, pain and flatulence are reported in less than 5% of treated patients. There are no reports of electrolyte imbalance after 48 weeks of follow-up.25

Guanylate cyclase C activators

Guanylate-cyclase activator belongs to a 3´-guanosine-5´monophosphate (cGMP) family of receptors that also include some heat-stable microbial ST-peptides.26,32 Guanylin receptors (GR) are widely distributed throughout the gut, but are more active in a pH neutral microenvironment.

Linaclotide is a 14-aminoacid peptide with agonist properties over GR; this stimulus leads to an increase in intracellular cGMP and subsequently to activation of Cl-sensitive channel (ClC) and to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR), finally resulting in an increase of water and bicarbonate secretion into the intestinal lumen that consequently, promotes intestinal motility.33 Some reports mention the increase in cGMP could have a beneficial role on visceral hypersensitivity, through a direct action in nerve endings.34 Guanilib is a synthetic analog of uroguanylin with a low rate of systemic absorption; currently this drug is under research on early-phase trials.

Clinical efficacy

in two recent phase-III RCT, that included 1200 patients, linaclotide at 150 and 300 ug/day showed significant beneficial effects including an increase in the number of CSBMs per week, improvement in abdominal bloating and abdominal discomfort, decrease in stool consistency and straining, together with a decrease in constipation severity rates, Also an increase in quality of life indices were seen.33

Adverse events

Diarrhea was the most frequent adverse event and was dose-dependent, usually classified as mild to moderate in severity; the rate of discontinuation due to side effects was 2.4%.33

Opioid Antagonists

Opioids analgesics are frequently used for the treatment of acute and chronic pain in malignant and non-malignant conditions. The pain relief is related to their action as an agonist on k and δ receptors; however opioids also exert an agonist action on µ-receptors leading to their undesirable Gi effects, including constipation. Often, opioid-related constipation represents a cumbersome and challenging condition with regards to treatment.35,36 Recently, two µ-antagonist receptors, methyl-naltrexone and alvimopan have become available for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation without compromising analgesic action.

Methyl-naltrexone

Methylnaltrexone is a quaternary-derivative opioid, m-receptor antagonist. Some N-terminal methylations increases its polarity by reducing its lipid solubility, these structural and chemical properties in turn, explains its inability to cross the blood-brain barrier, preventing central opioid action but keeping its peripheral action on m-receptors. This receptor antagonism induces an increase in intestinal motility and promotes intestinal secretion thereby accelerating gastric and oro-cecal transit time in healthy volunteers.37 Methylnaltrexone when administered subcutaneously reaches peak concentration in 0.5 hr with a half-life of 2.9 hours.37 Recently FDA has approved its use for in-hospital patients with opioid-induced constipation.

Clinical efficacy

Methyl-naltrexone also increases rate of CSBM and has a rapid onset for inducing first bowel movement, as well as improvement in constipation severity scores with a positive impact on quality of life.37,38 Recently, a systematic review showed that methyl-naltrexone reduces gastrointestinal transit time compared to placebo without compromising centrally-mediated opioid analgesic properties.39 Methyl-naltrexone has been shown to be efficacious in both malignant and non-malignant opioid-induced constipation conditions. In one study, cancer patients randomly assigned to receive methyl-naltrexone at different doses (1, 5, 12.5 and 20 mg) administered subcutaneously every other day, showed that ≥ 5 mg dose, induced a laxative effect, with 60% of patients showing passage of stools after 1 hr from administration.40 In methadone chronic users, methyl-naltrexone administered intravenously, showed immediate laxation together with a reduced overall gut transit time.41 A double blind randomized placebo-controlled study conducted on methadone users, showed similar results following intravenous infusion.42 Another study suggested that methyl-naltrexone is cost-effective for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation.43 Methyl-naltrexone has also been used for postoperative ileus, showing a decreased time for first bowel movement compared to placebo (dose 0.3 mg/kg; 1.1 hrs vs 3 hrs, p<0.01) as well as reducing the hospital length of stay (119 vs 149 hours, p< 0.05).37

Adverse events

Commonly reported adverse events are abdominal cramping (28%), flatulence (13%), nausea (11%) and dizziness (7%). Currently, there are no reports on long-term treatment with methyl-naltrexone.

Alvimopan

It has been shown that µ receptors are widely dis- tributed along the gastrointestinal tract. These are seven-transmembrane domains G protein-coupled receptors, located at close proximity of intestinal interneurons, secreto-motor neurons and interstitial cells of Cajal.44 Alvimopan has high affinity to µ receptors and low affinity for k and δ receptors. Alvimopan has poor penetration through the blood-brain barrier due to its large molecular weight, low polarity and its zwitterionic conformation.45,46

Mechanism of action is largely local due to a low systemic absorption (<6% bioavailability) as a result of alvimopan's higher intestinal metabolism mediated by enteric flora via amide-hydrolysis which in turn transforms it into its active metabolite ADl-08-0011.47 Alvimopan is more potent compared with methyl-naltrexone. Main excretion route is through the feces and there is no need for dose-adjustment with regards to renal function. Contrary to methyl-naltrexone, alvimopan is available for oral use.

Clinical efficacy

Several studies have shown that alvimopan, administered once before surgery and then twice a day after surgery decreases median time for first bowel movement, increases mean weekly bowel movements, decreases hard stools and the need for straining without compromising analgesic effects.48 Alvimopan at 6 to 12 mg orally, administered before a hysterectomy followed and then twice daily for 7 days in the postoperative period, reduces time to pass flatus, improves food tolerance and increases bowel movements.49 Alvimopan shortens hospital length of stay by one day and resulted in savings of $879 to $977 per patient in direct hospital costs.50,51

In non-cancer patients receiving chronic opioid treatment, alvimopan 5 mg orally, twice daily induces ≥ 3 spontaneous bowel movements (SBM) (72% vs 48%, p<0.001), decreases laxative rescue usage whereas improves opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (40.4% vs 18.6% placebo, p≤0.001) without increasing pain scores.52 In a study, comparing alvimopan, 5 mg once and twice daily versus placebo, a greater proportion of alvimopan-treated patients showed an improvement in SBMs compared to placebo, although it did not reach statistical significance (63% in both alvimopan groups vs 56% in placebo). However, alvimopan was superior for improving symptoms and overall well-being.53

Adverse events

Common adverse effects are nausea and vomiting.39 There were some concerns about whether alvimopan could increase the cardiovascular risk in patients with established coronary artery disease but to date; no significant adverse events have been reported in this regard. FDA has approved the drug for the treatment of postoperative ileus; however, this approval is restricted for use in hospitalized patients with adequate monitoring. The safety and effectiveness for long-term management of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction needs further research.

NKTR-118 is a new oral opioid antagonist that is being studied on opioid-induced constipation. Early studies show that it improves the number of SBMs per week without reversal of analgesia.54

Serotonergic enterokinetic agents

Serotonin (5-Hydroxitryptamine; 5-HT) is a neurotransmitter with extensive physiological functions in the human body. In the gastrointestinal mucosa, serotonin is produced by enterochromaffin cells which represent 90% of all serotonin.55 To date, fourteen serotonin receptors have been described. Of these compounds that out on 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors have been tested in Gi tract. These are G protein-coupled receptors that are found in smooth muscle cells, enterochromaffin cells, myenteric plexus neurons and primary afferent neurons. This wide distribution, promotes its actions on gut motility. 5HT4 agonist increase peristalsis by increasing proximal smooth muscle contraction and distally it inducing smooth muscle relaxation. This receptor also modulates chloride secretion as well as pain modulation. In the other part of the spectrum, 5HT3 antagonism, decreases postprandial colonic motility and delays colonic transit.56

5-HT4 agonist receptors

Several 5-HT4 agonists have been described for constipation treatment, including benzamines (cisapride, renzapride, mosapride and prucalopride [benzofuran]), indoles (tegaserod) and benzimidazolones (activation of chloride receptors -cystic fibrosis-). There are some individual differences among these subclasses with regards to their degree of activation on serotonine, mainly explained by the make up of their chemical structures.57

Several studies have suggested that cisapride may be useful in CC. Some have showed an increase in frequency of bowel movements, ease of defecation and decrease in laxative consumption when compared to placebo. Cisa-pride has been withdrawn from US and European market due to cardiac toxicity (prolonged QTc) but remains in use in several Latin-American countries. However, evidence is scarce to make a statement regarding its long term use.58 There was some interest with renzapride, however some clinical trials showed an increase the risk of ischemic colitis and subsequently, the drug was withdrawn definitively.59

Mosapride has been recently investigated. In a clinical trial involving diabetic patients with constipation, mosapride at 5 mg/day, significantly increased the number of bowel movements with an additional benefit of improving glycemic control when compared to domperi-done.60 Others have reported an improvement in rectal sensori-motor function and in colonic motility on patients with irritable bowel syndrome-predominant constipation during treatment with mosapride.61

Several RCT studies have shown that tegaserod is effective in the treatment of CC by improving CSBM, decreasing straining, bloating and abdominal distention at doses of 2 and 6 mg twice daily, orally.62 Commonly reported side effects are abdominal pain, transient diarrhea, headache and nasopharyngitis. However, tegaserod was withdrawn on March, 2007 in USA because of concerns related to ischemic cardiovascular adverse events. At present, tegaserod is available in the United States and Europe only under restricted prescription for use in female CC and iBS-c patients less than 55 years old without significant cardiovascular risk.63

Prucalopride is a selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist, which exerts its prokinetic effect through increasing cholinergic and non-cholinergic-non-adrenergic neurotransmission. Prucalopride shows 90% bioavailability after oral intake and has a half-life of up to 20-30 hours. It does not undergo CYP3A4 metabolism, and hence has lower interaction rates. At doses from 0.5-4 mg, pru- calopride accelerates colonic transit in healthy volunteers that is reflected as an increase in stool frequency and improvement in stool consistency compared to placebo.64 Efficacy has been shown in 3 RCTs.64,66 Maximal benefit is seen with 4 mg dose and patient satisfaction re- mains after 12 to 24 months of treatment.64 Common side effects are headache, nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhea. No cardiovascular concerns to date.

Velusetrag (TD-5108) is a highly selective 5-HT4 agonist. An early trial (four weeks) in CC patients showed a dose-dependent increase in orocecal transit as well as in SBM, frequency and at different doses (15, 30 or 50 mg) when orally administered.65,66 Naronapride (ATi-7505), is another 5HT4 agonist which is now under pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic research. Naronapride exerts effects on hERG channels. At doses of 80 mgs administered orally it has showed an increase the number of SBM. Naronapride will be available for phase ii clinical trials in the near future.67

Neurotrophin-3

Neurotrophin-3 belongs to neurotrophins, a grown-factors family related with the development and maintenance of central, peripheral and autonomic neurons that play an important role in the development of enteric nervous system. An open-label study showed that neurotrophin 300 ug/Kg subcutaneously, three times a week, produce increase in stool frequency, improves passage of stools and promotes softening of stools.68 In a phase ii RCT, 107 chronic constipated patients (Rome II) received 3 mg, 9 mg or placebo. Compared to placebo, patients that received 9 mg, showed an increase in number of CSBM as well as a dose-related stool-softening.69 Commonest adverse events were minor injection site reactions in 33%. Importantly, 50% of patients developed anti-neurotrophin antibodies after finishing this trial. Whether anti-neurotrophin antibodies may or may not reduce its efficacy in long term treatment is currently unknown.

Colchicine

Colchicine is a plant alkaloid commonly used in the treatment of gout and Mediterranean fever. Colchicine's mechanism of action is related with its commonest adverse effect, which is diarrhea, providing a therapeutic rationale for constipation through prostaglandin production which in turn, induces intraluminal secretion and intestinal motility.70 In two small RCT, colchicine 0.6 mg three times a day, showed an increase in number of SBM and a reduced colonic transit time as compared to baseline values. Long term therapy has few adverse events, most commonly diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.71 Rarely, neuropathy and myopathy have been described with prolonged use. Further studies are needed to define the role of colchicine in treating CC.

Motilin agonists

Motilin is a 22 aminoacid-peptide secreted by enterochromaffin cells. Motilin stimulates gut motility through activation of a G protein-coupled receptor widely distributed in enteric nervous neurons and intestinal smooth muscle cells.72 Erythromycin represents a classic example of these drugs. The mechanism of action is related to an activation of motilin receptors. Although it is highly effective for short-term, prolonged treatment induces tachyphylaxis, limiting its therapeutic effectiveness. Mitemcimal is a non-antibiotic motilin-agonist that has been tried in two trials in IBS and gastroparetic patients.73 More studies are required with this drug.

Probiotics and prebiotics

Probiotics are live organisms that, once ingested in adequate amounts, exert a health benefit to the host (lactobacillus, non-pathogenic yeast). Prebiotics are non-digestible and fermentable compounds serving as a substrate for gut microflora, stimulating its growth and activity. These effects may promote certain benefits in gastrointestinal motility. Data about their effect on CC are scarce. Bifidobacterium animalis has been shown to accelerate colonic transit in healthy individuals and patients with iBS, suggesting a direct effect on colonic motility. Two RCTs have shown benefit after treatment with Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173,010.6.10

Conclusions

Today, several treatment options are available for the management of CC. However, there is a need for developing clear guidelines for these medications because some appear to work well in patient populations whereas so- me others respond better to drugs with different mechanism of action and some show better results with a combination of these drugs. A thorough clinical assessment together with an adequate diagnostic evaluation will provide important pathophysiologic information that will allow better characterization of the specific subpopulation of constipated patients which in turn, will help to guide the best treatment option.

Received: January 2012. Accepted: March 2012

Corresponding author:

Satish S. C. Rao.

Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology,

Medical College of Georgia/Georgia Health Sciences University.

1120 15th Street, BBR 2538,

Augusta, GA. Z.P. 30912.

Telephone: 706-721-2238. Fax: 706-721-0331.

E-mail: srao@georgiahealth.edu