The stigmatization and discrimination of non-heterosexual persons is a reality in some institutions of the Health Services, and among health sciences students.

ObjectivesTo describe and predict the level of sexual prejudice in health sciences students, taking into account a set of qualitative and numerical variables on socio-demographic data, sexual life, social life, university (private or public) the student's major (medicine or psychology), and clinical aspects.

MethodologyA socio-demographic and life-history data questionnaire, an 8-item homophobia scale and a 16-item internalized homonegativity scale were applied to a non-probabilistic sample composed of 231 health sciences students. The predictive models were estimated by analyses of multinomial and ordinal regression.

ResultsTwelve percent of participants exhibited an attitude of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons (including 0.9% who exhibited extreme rejection). Non-heterosexual orientation, having non-heterosexual friends and acceptance of one's own homosexual desires were variables associated with lower levels of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons. Only the two latter variables were significant predictive variables; they explained 21% of the variance in the ordinal regression model and 27% in the multinomial regression model. The percentage of the correct classification of cases of acceptance was high but the percentage of the correct classification of cases of rejection was low.

ConclusionThe level of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons is low. An exclusively heterosexual identity, affirming not to share aspects of the sexual sphere and not having personal contact with the stigmatized subject are determinants of open rejection. There exist other variables that were not taken into account in this study, as is deduced by the high percentage of unexplained variance.

Homophobia can be defined as an extreme rejection towards people who have sexual practices and/or an erotica-affective orientation directed towards individuals of the same sex. It involves attitudes ranging from fear and avoidance to reactions of aggression.1 The term “homophobia” has been criticized owing to its psychopathological connotations, for it makes a direct reference to a specific phobia. Most investigators prefer to conceptualize homophobia as an attitudinal phenomenon of rejection, and the term sexual prejudice has been proposed.2

Nowadays, even though open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons has tended to disappear and has been penalized, subtle rejection has still remained in Western society.3,4 This subtle rejection stems from an ideology that has been termed heterosexism by social researchers, a concept that involves a tendency to assume that everybody is, or should be, heterosexual.5 This ideology contends that heterosexuality is the only natural sexual orientation, and that heterosexual persons are superior to non-heterosexual persons. Therefore, all deviations from the hegemonic pattern should kept at bay and without prestige or power.6 Just like homophobia, heterosexism generates a strong rejection towards one's own homosexual desires, as well as strong conflicts when integrating the behaviours motivated by this desire into a positive identity.7

Since the emergence of the HIV epidemic, it has been pointed out that the group of men who have sex with men are the main culprit for the spread of the epidemic, reviving ancient, deep-rooted prejudices against homosexuality.8 The stigmatization and discrimination of persons living with HIV, especially those with a non-heterosexual orientation, still exists in some institutions of the Health Services in Mexico,9 and this is also visible among young students in the process of professional formation.10 This differential treatment, even though it is more disguised and subtle, is negatively perceived by non-heterosexual persons and often reported to the authorities of the health services. Currently, there is a great deal of sensitivity towards this issue in some schools of medicine and health sciences around the world and, as a result, efforts are being made to evaluate the level of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons; likewise, workshops aimed at encouraging a greater level of acceptance of sexual diversity and at promoting a greater level of empathy towards persons living with HIV have been implemented at those schools.11 This is a pending issue in Mexico.12

Campo and Herazo (2008), in a systematic review of studies published from 1998 to 2007, found that the percentage of medical students harbouring an attitude of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons ranged from 10% to 25%.13 Likewise, Campo et al. (2010), in another systematic review, found that from 7% to 16% of nursing students harboured an attitude of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons.14 Similarly, Parker and Bhugra (2000) reported that from 10% to 15% of British medical students expressed a negative attitude towards non-heterosexual persons.15 Furthermore, among American medical students, Skinner et al. (2001) found that 12% of men expressed rejection towards non-heterosexual men.16

In Mexico, Moral and Martinez (2012) found an attitude of rejection in about 6% of psychology students, and extreme rejection was found in approximately 2%.17 Moral and Valle (2011) found an attitude of rejection in approximately 19% of medical students, and extreme rejection was found in about 3%.18 In the research performed by Moral and Martinez (2012),17 the attitudinal scale had more contents on open rejection than the scale used in the study performed by Moral and Valle (2011).18 Other differences were that, in the study performed by Moral and Martinez,17 the students were enrolled at a public university and had been exposed to the influence of programmes on sexuality; in contrast, the participants in the study performed by Moral and Valle (2011)1 were enrolled at a private university and had not been exposed to programmes on sexuality, a fact that could explain the lower level of acceptance among these later students.

The term homonegativity has also been proposed to replace the term homophobia, since it does not imply any stigmatizing connotation.19 The distinction between internalized and externalized homonegativity is done in the specialized literature, and makes references to the evaluated population. The adjective “internalized” is used when the evaluation is carried out in non-heterosexual persons (rejection towards themselves owing to their sexual orientation), and the adjective “externalized” is used when the evaluation is carried out in heterosexual persons (rejection towards the others owing to their sexual orientation).20,21 However, a broader use of the concept of internalized homonegativity has been proposed.19 When one considers that any person, regardless of self-defined sexual orientation, can harbour homosexual fantasies and desires (potential bisexuality) and may experience fear of revealing these feelings and/or displaying deviant behaviours from their expected gender role, then the concept of internalized homonegativity can be applied to any person, because it emphasizes the internal experience of rejection towards oneself and the prejudicial gaze from the other, especially within a society with heterosexist values in which subtle rejection towards non-heterosexual persons still remains.19 In the present study, the concept of internalized homonegativity receives this broader sense.

Determinants of sexual prejudice from a psycho-socio-cultural viewThe extreme rejection towards non-heterosexual persons possesses distinct, although non-exclusive, socio-cultural determinants.22 This rejection becomes internalized during the socialization process in the family of origin, school, and church.20 The individuals who adhere closely to the religions prevailing in the Western world (such as Catholicism or other branches of Christianity), which have held a posture of overt rejection towards homosexuality, tend to exhibit attitudes of stronger rejection towards non-heterosexual persons as compared to individuals who are less religious or who do not have any religious adscription.23 Bearing in mind the influence of environmental factors, these attitudes of rejection could be turned into attitudes of greater acceptance through positive experiences and direct personal contact with individuals who are the victims of social discrimination.24

In this context, it should be noted that the attitude has essentially an expressive function, which facilitates the acceptance, adaptation, and identification with a social group with which the individual interacts daily. As the individual matures, he/she feels more secure of his/her identity and becomes more independent from the group to which he/she belongs; thus, the expressive function of attitude becomes more flexible and the defensive aspect of the attitude might even disappear. Consequently, the attitude towards non-heterosexual persons may be rigid in adolescents and individuals with no sexual experience, since the evolutionary task of demonstrating their own heterosexuality is still unresolved. During the period of time in which individuals are building a heterosexual identity, through a process of maturation and consolidation of sexual orientation, their attitude towards non-heterosexual persons will exhibit a greater level of rejection than the level observed in persons who have already built their identity.23 On the other hand, this attitude may be more flexible in older individuals, for they have acquired more sexual experience and have developed a clearer perception of their own sexual orientation (heterosexual or non-heterosexual).25

The societal attitude towards both non-heterosexual men and women exhibits rejection, although the level of rejection expressed towards non-heterosexual men is greater than the level of rejection towards non-heterosexual women.21 This is evident not only in legal practices, but also in the violent attacks, defamatory gossip, sexual jokes, humiliating pranks, and stigmatizing insults directed towards non-heterosexual persons.4,26 Hence, men probably internalize and reject homosexuality more than women do.7,20 Men and women tend to exhibit greater rejection towards homosexuality in their own gender for they put the attitude at the service of the expression of a heterosexist ideology and the consolidation of a heterosexual identity.4,27

Aims and hypothesesThe aims of this study are: (1) to describe the level of sexual prejudice in students of the Health Sciences, and (2) to predict the rejection towards non-heterosexual persons, considering variables about socio-demographic data, sexual life, social life, university (private or public) in which the participant studies his/her career (medicine or psychology), and the clinical aspects (having been tested for HIV, and having taken clinical care of persons living with HIV).

The level of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons is expected to be low because of the change in attitude that has taken place in contemporary society, where the attitude of blatant rejection has tended to fade away and to give way to an attitude of subtle rejection.28 The variables that are expected to be significant and have a predictive value for identifying non-prejudiced persons are the following: female sex, older age, a self-defined non-heterosexual orientation, not having any religious adscription, acceptance of one's own homosexual desires, having begun an active sex life, having had a greater number of sexual partners, having non-heterosexual friends, having friends living with HIV, and having taken clinical care of persons living with HIV.21,29 It is also expected that the variables related to the age at which participants began their active sex life, the years elapsed after the first sexual relation, and having been tested for HIV, will have a weaker, or a non-significant, association with sexual prejudice because these experiential variables may be determined by very different situations, in which personal control or voluntary intention may vary.21,29 Regarding university (private or public) in which the participant studies his/her career (medicine or psychology), a greater level of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons is expected among the medical students from the private university than among the psychology students from the public university owing to: (1) the presence of a greater proportion of men among medical students than among psychology students, as the expectation is to find a higher level of rejection among men than among women;27 and (2) the presence of more conservative values in the families of students who attend a private university, as the expectation is to find a higher level of rejection among persons or institutions with more conservative values.30

Methods and materialsA non-experimental study with a cross-sectional design was carried out. A non-probability sample of 231 health sciences students from three universities from northeast Mexico was collected. This sample was composed of 100 (43%) participants surveyed at the medical school of Universidad Autonoma de Coahuila; 66 (29%) participants surveyed at the School of Medicine of Tecnologico de Monterrey; and 65 (28%) participants surveyed at the School of Psychology of Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon. The following questionnaire and scales were used as instruments of assessment:

The questionnaire was composed of a set of close-ended questions about socio-demographic data (sex, age, and religious adscription), sexual life (self-defined sexual orientation, having begun an active sex life or not, age at the beginning of active sex life, and number of sexual partners), social life (having non-heterosexual friends or friends living with HIV), and clinical aspects (having been tested for HIV, and having taken clinical care of persons living with HIV).

The Scale of homophobia (HF)29, adapted to the Mexican population, was used31. The scale was designed to assess the level of sexual prejudice in students of health sciences. The original version was composed of 12 Likert-type items with 4 options of answers and a range of 1–7: 1=“completely in disagreement”, 3=“in disagreement”, 5=“in agreement” and 7=“definitely in agreement”. In the Mexican adaptation31, two items were discarded because they were considered as non-applicable: “I feel more negative towards homosexuality since AIDS” and “Homosexuality is a mental disorder”. The first item was excluded because the AIDS epidemics has more than 30 years of history; and the second one because homosexuality has been completely eliminated from medical classifications since the late 1980s. Besides, this latter item was the most skewed one towards disagreement in the original study. Once the internal consistency and factor structure were determined, the authors recommended reducing the scale to one factor (open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons) composed of 8 items (HF-8). The internal consistency of these 8 items was high (α=.84), and this one-factor model showed fit indexes to data that ranged from good to adequate.31

The Scale of Internalized Homonegativity (IHN-16)19 is composed of 16 Likert-type items with 5 options of answers and a range of 1–9. Its internal consistency was high (α=.88), and showed a factor structure composed of 3 factors: rejection towards public manifestations of homosexuality (α=.81); rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity (α=.81); and inability for intimacy by non-heterosexual individuals (α=.69). A model of three factors hierarchized to a general factor showed fit indexes to data that ranged from good to adequate19. In this study, the factor of rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity was the only one used.

The assessment instruments were administered to the participants in the classrooms by the authors. The survey was conducted from January to May, 2012. The participants were requested to provide informed consent for their participation in the study. In this first page the informed consent was made explicit by participants (without signature). Anonymity and confidentiality of the information supplied were guaranteed in accordance with the research ethical norms recommended by the American Psychological Association.32 For this reason, personal identification data were not requested. The authors obtained approval from Institutional Committees for ethical and research issues.

ResultsSample descriptionThe sample was composed of 121 women (54%) and 103 men (46%); these frequencies were statistically equivalent (binomial test: p=.26). The mean age of the participants was 19.13 years (SD=1.68). All participants were college students. 231 out of 166 participants (72%) studied medicine and 65 (28%) psychology, 165 students (71%) were enrolled at public universities and 66 (29%) at a private university. Regarding their religious adscription, 79% (182 out of 231) identified themselves as Catholics; 4% (10) identified themselves as belonging to other branches of Christianity, and 17% (39) identified themselves as followers of other religions or holding personal religious beliefs.

Self-defined sexual orientation was heterosexual in 95% (220 out of 231) of the participants, bisexual in 3% (7), and homosexual in 2% (4). When asked whether or not they had begun their active sex life, 38% (88 out of 230) answered yes and 62% (142) answered no. Among the 88 sexually active participants, the mean number of sexual partners was 3.11 (SD=5.86), and mean age of beginning an active sex life was 17.07 (SD=1.54) within a range from 13 to 25 years old. To the question “Do you have homosexual friends?”, 75.5% (173 out of 229) said yes and 24.5% (56) said no; and when asked if they have friends living with HIV, 2% (5 out of 227) answered yes and 98% (222) answered no. When asked whether or not they had been tested for HIV, 17.5% (40 out of 228) answered yes and 82.5% (188) answered no. When asked whether or not they had taken clinical care of persons living with HIV, 12% (28 of 227) answered yes and 88% (199) answered no.

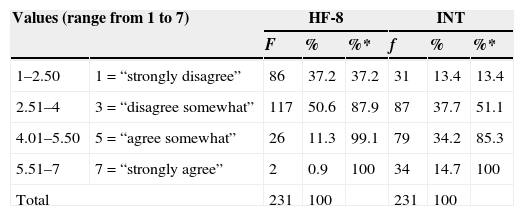

Levels of sexual prejudice (homophobia) and rejection of the homosexual desireIn order to interpret levels of sexual prejudice, the HP-8 total score was transformed into an ordinal variable with 4 levels corresponding to the four response tags of its items. The total score of the HP-8 scale was divided by the number of items to obtain scores in a continuous range from 1 to 7. This continuous range was divided into four constant-amplitude intervals, ([maximum value−minimum value]/number of intervals=[7–1]/4=1.5) to make them correspond to the 4 discrete values of answers of the items: from 1 to 2.50 (discrete value 1=“totally in disagreement” with rejection towards non-heterosexual persons); from 2.51 to 4 (discrete value 3=“in disagreement”); from 4.01 to 5.50 (discrete value 5=“in agreement”); from 5.51 to 7 (discrete value 7=“definitely in agreement”). This way the predicted ordinal variable was obtained, and the levels of sexual prejudice in the sample could be easily interpreted. The range of scores for the factor “rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity” of the IHN-16 scale was also reduced to a continuous range from 1 to 7. Once the scores were divided by their number of items, it was necessary to multiply by a constriction coefficient ([maximum value−minimum value of scale with narrower range]/[maximum value−minimum value of scale with wider range]=[7–1]/[9–1]=0.75) and add a constant (1 – constriction coefficient=0.25). This way, the range was constricted from 1–9 (original range for IHN-16) to 1–7 (range corresponding to HP-8).

Total disagreement with the open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons and with the rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity was found in 37% and 13% of the participants, respectively. The medians of the distributions corresponded to the discrete value 3 (“in disagreement”). The distribution of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons showed a positive skew. The distribution of rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity was symmetric, with about one half (51%) expressing acceptance and one half (49%) expressing rejection (Table 1).

Distribution of HF-8 scores and the HNI-16 factor related with rejection of one's own homosexual feelings, desires and identity (INT).

| Values (range from 1 to 7) | HF-8 | INT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | % | %* | f | % | %* | ||

| 1–2.50 | 1=“strongly disagree” | 86 | 37.2 | 37.2 | 31 | 13.4 | 13.4 |

| 2.51–4 | 3=“disagree somewhat” | 117 | 50.6 | 87.9 | 87 | 37.7 | 51.1 |

| 4.01–5.50 | 5=“agree somewhat” | 26 | 11.3 | 99.1 | 79 | 34.2 | 85.3 |

| 5.51–7 | 7=“strongly agree” | 2 | 0.9 | 100 | 34 | 14.7 | 100 |

| Total | 231 | 100 | 231 | 100 | |||

%*=cumulative percentage.

As a first step, the significantly correlated variables to the score of the HP-8 scale (reduced to a range of four discrete values) were identified. For this purpose, Cramer's V coefficient was used for the qualitative variables, and Spearman's rho correlation coefficient was used for the numerical variables. The numeric variables were 5 (age, age of beginning active sex life, years elapsed after the first sexual relation, number of partners, and rejection of own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity), and the qualitative variables were 10 (sex, being heterosexual/non-heterosexual, having begun/not having begun active sex life, having/not having non-heterosexual friends, having/not having friends living with HIV, having/not having been tested for HIV, having/not having taken clinical care of persons living with HIV, university [private or public], career [medicine or psychology], and religious adscription). One out of the 5 numerical variables (rejection of one's own homosexual desires expressed within a continuous range of 1–7 [rS=.48, p<.01]), and 2 out of the 10 qualitative variables (not having non-heterosexual friends [V=.29, p<.01] and heterosexual orientation [V=.21, p=.02]) correlated to the score of the HP-8 scale.

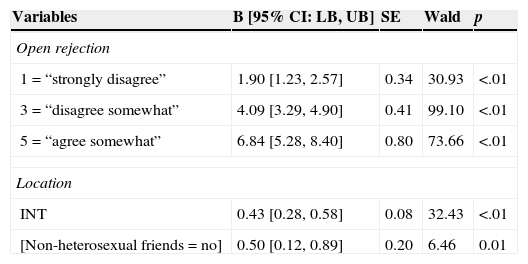

As a second step, a model of ordinal regression was estimated with the three significant correlates. Because of the bias of the predicted ordinal variable towards the low values, the link function was calculated by the negative log–log method.33 One of the variables did not have a significant weight: sexual orientation (B=0.85 [95% IC: −0.59, 2.28], SE=0.73, Wald [1]=1.34, p=.25). As a result, the model was estimated again and the sexual orientation was eliminated.

The model with two predictive variables was significant (χ2[2,N=229]=46.65, p<.01). The two predictive variables had significant weights, as well as the three values of the predicted variable, taking the discrete value 7 as a reference value. The model indicated that individuals with lower levels of sexual prejudice are more likely to have non-heterosexual friends and to accept their own homosexual desires than the individuals with higher levels of sexual prejudice (Table 2). The model explained 21% of the criterion variance using Nagelkerke's pseudo-R2 coefficient. The model showed goodness of fit by the Pearson's test (χ2[121,N=229]=117.86, p=.56). The assumption that the location parameters (slope coefficients) are statistically equivalent throughout the 4 ordinal categories of answers by the parallel-lines test with a bilateral level of significance of .05 was rejected, but it would have been accepted if the significance level had been equal to .01 (χ2[4,N=229]=11.28, p=.02). This model correctly classified 55% of the participants, and had a greater number of correct classifications in the low values than in the high values.

Parameter estimation of the ordinal regression model.

| Variables | B [95% CI: LB, UB] | SE | Wald | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open rejection | ||||

| 1=“strongly disagree” | 1.90 [1.23, 2.57] | 0.34 | 30.93 | <.01 |

| 3=“disagree somewhat” | 4.09 [3.29, 4.90] | 0.41 | 99.10 | <.01 |

| 5=“agree somewhat” | 6.84 [5.28, 8.40] | 0.80 | 73.66 | <.01 |

| Location | ||||

| INT | 0.43 [0.28, 0.58] | 0.08 | 32.43 | <.01 |

| [Non-heterosexual friends=no] | 0.50 [0.12, 0.89] | 0.20 | 6.46 | 0.01 |

Link function calculated by the negative log-log method. INT=rejection of one's own homosexual feelings, desires and identity. Reference value 7=“strongly agree”. B=coefficient of determination. CI=confidence interval. LB=lower bound. UB=upper bound. SE=standard error of the coefficient of determination.

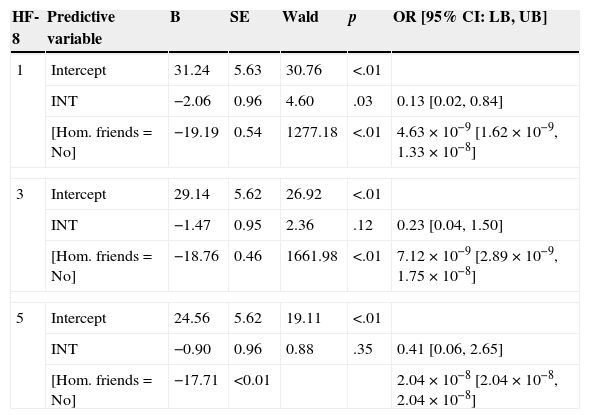

Since the assumption of equivalence among the location parameters (slope coefficients) across four response categories of the predicted ordinal variable was not met (contrasted by the test of parallel lines), it was decided to estimate the model using multinomial regression.33 As in the previous analysis, sexual orientation (χ2[3,N=229]=1.90, p=.58) did not have a significant weight and therefore was eliminated. The model with two predictive variables was significant (χ2[6,N=229]=59.62, p<.01). The factor of rejection towards one's own homosexual desires (χ2[3,N=229]=41.84, p<.01) and having non-heterosexual friends (χ2[3,N=229]=12.23, p<.01) had a significant weight. The model showed goodness of fit by the Pearson's test (χ2[117,N=229]=84.38, p=.99), and explained 27% of the variance of the open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons based on Nagelkerke's pseudo R2 coefficient. The model correctly classified 61% (139 out of 228) of the participants: The percentage of correct classifications in the answers totally in disagreement with the open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons was 53% (45 of 85), in the answers of disagreement 79% (92 of 116), in the answers of agreement 8% (2 of 26), and in the answers of total agreement 0% (0 of 2). The reference category was the ordinal value 7, which corresponds to the answer category “definitively in agreement”. In the model for predicting discrete value 1 (“totally in disagreement”), the two predictive variables were clearly significant when classifying the participants in this group or in the reference group (discrete value 7). In the model for predicting the discrete value 3 (“in disagreement”) and in the model for predicting the discrete value 5 (“in agreement”), the variable related to rejection towards one's own homosexual desires did not have a significant weight (Table 3).

Parameter estimation multinomial regression model.

| HF-8 | Predictive variable | B | SE | Wald | p | OR [95% CI: LB, UB] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intercept | 31.24 | 5.63 | 30.76 | <.01 | |

| INT | −2.06 | 0.96 | 4.60 | .03 | 0.13 [0.02, 0.84] | |

| [Hom. friends=No] | −19.19 | 0.54 | 1277.18 | <.01 | 4.63×10−9 [1.62×10−9, 1.33×10−8] | |

| 3 | Intercept | 29.14 | 5.62 | 26.92 | <.01 | |

| INT | −1.47 | 0.95 | 2.36 | .12 | 0.23 [0.04, 1.50] | |

| [Hom. friends=No] | −18.76 | 0.46 | 1661.98 | <.01 | 7.12×10−9 [2.89×10−9, 1.75×10−8] | |

| 5 | Intercept | 24.56 | 5.62 | 19.11 | <.01 | |

| INT | −0.90 | 0.96 | 0.88 | .35 | 0.41 [0.06, 2.65] | |

| [Hom. friends=No] | −17.71 | <0.01 | 2.04×10−8 [2.04×10−8, 2.04×10−8] | |||

The reference category is the value 7=“strongly disagree”. INT=rejection towards one's own homosexual feelings, desires and identity. B=coefficient of determination. SE=standard error of the coefficient of determination. OR=odds ratio. CI=confidence interval. LB=lower bound. UB=upper bound.

The percentage of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons was low. Less than one eighth of the participants exhibited an attitude of rejection, including extreme rejection which was present in approximately one out of 100 participants. On the other hand, the rejection towards own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity was present in nearly fifty percent of the participants, including extreme rejection in approximately one seventh. These data support the hypothesis that stems from the current heterosexist ideology.2,5 That is, homosexuality is tolerated, but only after making it clear, both before others and one's own conscience, that one is a heterosexual person and does not harbour homoerotic feelings. It should be noted that the percentage of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons that was found in this study is equivalent to the percentage found by Klamen et al. (1999), through the use of the same scale, in a sample of American students (13%).29 Nevertheless, the percentage of open rejection was lower in our sample than in the sample of Klamen et al. (1999), who found extreme rejection in 2.75% of participants. There is a time difference of one and a half decades between the two studies. During this time period acceptance and tolerance towards non-heterosexual persons have been growing in the Western world, which could explain the lower portage of extreme rejection in the present study. Consistent with the criminalization of discrimination and attacks against these people, nowadays the blatant repulse is decreasing.2

The percentage of rejection found in this study was similar to the percentage found in other studies on attitude towards non-heterosexual persons among students of health sciences from Western countries. The mean rejection percentage was 14%, taking into account the studies performed by Campo and Herazo (2008) [10–25%],13 Herazo and Cogollo (2010) [7–16%],14 Parker and Bhugra (2000) [10–15%],15 and Skinner et al. (2001) [12%].16 During the last fifteen years, what appears to be declining is not so much the total rejection, but rather the extreme rejection, which is becoming a subtle non-acceptance.2

Clearly the percentage of rejection in the present study was lower than the percentages obtained in other studies by means of instruments containing factors of subtle rejection, as the scale of subtle and manifest homophobia,34 test of implicit attitude towards homosexuality35 and the scale of internalized homonegativity, in which the percentages of rejection in subtle aspects were higher than 33%.19 These differences are consistent with the above interpretation of the evolution of rejection towards the subtle rejection in detriment of the manifest rejection.

The percentage of rejection reported in this study is located at the midpoint between the percentages that were found in the two Mexican studies previously cited. In this research, as in that performed by Moral and Martinez (2012),17 a scale with more contents on open rejection was used; likewise, as in the study performed by Moral and Valle (2011),18 students had not been exposed to the influence of programmes on sexuality. In this study, the participants were studying either psychology or medicine, but the school in which the participants were studying had no significant effect on the level of rejection. Similarly, the fact of studying at a public or private university had no significant effect. Therefore, the differences or similarities found among the 3 Mexican studies should not be attributed to the fact that the participants were studying medicine or psychology, or at a private or public institution. Differences should be attributed to the influence of sex education programmes; their presence has a significant effect.

The students of medicine at the private university did not show greater rejection towards non-heterosexual persons than the medicine students at the public university, possibly owing to similar sexual values between two institutions. Besides the possible effect of the public or private institution30, the fact that students came from two different cities could have had an impact on attitude,36 but it was not the case. The public university was located in a small city (Saltillo) and the private university in a big city (Monterrey). A greater rejection and more conservative values could be found among persons who live in a town or small city in compared to persons who live in a big city.36 The expectation of finding a greater level of rejection of non-heterosexual persons among medical students than among psychology students was not met either; although there were more women among psychology students and all of these latter students came from the big city (Monterrey), which facilitates acceptance.27,36 Therefore, the distribution of attitude seems fairly homogenous among students regardless of sex and the fact of studying a career of medicine or psychology, belonging to a private or public university, or living in a big city or a small city. This homogeneity might be attributed to their degree of schooling and the fact of studying health sciences, in which bioethical issues are addressed.

As was expected6,25, sexual orientation was associated with lower levels of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons, but this variable did not reach a statistically significant weight in the predicting models. The individuals with a heterosexual orientation are more likely to reject homosexuality than those with a non-heterosexual orientation, but, according to the heterosexist ideology, open rejection is avoided by the majority of the individuals, and that explains why it finally loses predictive power. Nowadays, it seems that the tendency is to opt for subtle rejection.2 Also, it should be taken into account that the percentage of participants with non-heterosexual orientation was low in the sample (5%), which lowers variability or presence of this variable in the four groups of levels of rejection, causing the statistical test to not select sexual orientation as a significant predictive variable. Therefore, it might be more helpful, for predictive aims, to use a numerical variable (frequency of homosexual thoughts, desires, fantasies and behaviours), and statistical tests that employ the full range of scores, such as multiple linear regression analysis or path analysis. In the present study, most of the potential predictive variables, including self-defined sexual orientation, were qualitative variables. The two analyses previously mentioned require using only numerical predictive variables, and for this reason those analyses could not be applied and ordinal regression was used instead.33

Having non-heterosexual friends was a variable related to the potential to predict a low level of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons; therefore, being in friendly contact with people who are victims of stigma and subtle non-acceptance has a strong effect on the attitude and on the rejection of the attacks on homosexual persons, modifying their attitudinal schemes.22,23 In order for this personal contact to modify the stereotype towards a more human and sensitive representation, Overby and Barth (2002) pointed out several conditions that should be present in the interaction: it should be cooperative and non-competitive; it should be supported by institutional authority figures; there should be mutual confidence; there should be some equivalence in socio-economic status and educational level; and there should be shared beliefs and values.37

As was expected, the variable more strongly associated with the rejection towards non-heterosexual persons and with the highest predictive power was the acceptance of one's own homosexual desires. Only if the individuals are able to overcome the prohibition, imposed by heterosexist ideologies, of harbouring homosexual desires, will they be able to develop, regardless of sexual orientation, a greater acceptance of persons who have a sexual orientation towards individuals of their own sex. From a psycho-social perspective, it has been argued that the conflict with one's own homosexual desires is a consequence of internalization of societal attitudes of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons during the individual's socialization process; thus, the individual will live in conflict until he can overcome this internalized homonegativity.6 On the other hand, the expressive function of attitudes emerges in situations in which personal identity or affiliation issues need to be self-affirming. For this reason, the persons who self-define as non-heterosexuals will show a much higher level of acceptance towards members of their own group despite living in a heterosexist society that devalues alternative sexualities.21

It was expected that the highest level of acceptance was among the participants without religion.23,38 In the sample of this research, none of the students declared themselves without religion. One could interpret that the lack of participants without religion reduced the variability of religious adscription and finally hampered this qualitative variable being a statistically significant predictive variable. Among the response options on religious adscription in the questionnaire of this study the option “without religion” was not included, but no one complained during the administration of the questionnaire. The participants who would have chosen the option “without religion” were probably among those who chose the option “other religions” (38 cases). This group represented 16% of the sample. This percentage coincides with the 16% of university students without religion and believers in other religions found by Moral (2010)38. It is also close to the 13% of persons without religion, believers who did not belong to any religious organization and believers in other religions among participants with higher education from the survey ENCUP-2012.39 The sample was collected at a time of exacerbation of apocalyptic themes. This might have motivated people who in other circumstances would have declared themselves as atheists; at that time, they preferred to adopt a more open stance to religious ideas. Considering this, the questionnaire introduced a bias that caused the absence of participants without religion. These cases were not lost, but were in the group of believers in other religions, as cases of believers in personal religious ideas proceeding from dominant religions and the New Age movement. The latter religious movement is characterized by an attitude of greater acceptance towards sexuality40, as it is also seen in persons without religion.38 Consequently, the mean of rejection among believers in other religions was the lowest. Hence the lack of significance of religious adscription on the open rejection cannot be attributed to the absence of participants without religion. This lack of association indicates that blatant condemnation is rejected regardless of religious adscription, and reflects a change in the dominant religions, which are evolving towards tolerance.41

The other 12 variables included in this study did not reach a statistical significance, though they were all potentially relevant in predicting open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons and adjusted to the expectations of (positive or negative) association. This is because there are few cases of open rejection, as opposed to the many cases of acceptance, which generates a strong asymmetry, and would require a very clear association to become statistically significant. On the other hand, the limited sexual experience and limited clinical practice of these students should be taken into account, as most of them are late adolescents; these two aspects affect variables such as the number of sexual partners or having taken clinical care of persons living with HIV.

On the other hand, the regression models explained low percentages of variance (less than one fourth of variance in the ordinal regression model and slightly more than one fourth in the multinomial regression model). They classified the levels of acceptance very well, but showed a very low percentage of correct classification in the cases of rejection. Perhaps there are other important variables that were not taken into account in this study, like the attitude of the family of origin and the genetic factor of the attitude.22,42 Likewise, two of the main causes of the limitations of these models might have been the qualitative nature of the variables and the non-parametric analyses that were employed. Surely, the use of numerical variables and parametric analyses, such as linear regression and path analysis, will help to achieve a higher percentage of explained variance in future research.

This study has several limitations. A non-probability sample of students of the health sciences was recruited from several universities in Northeast Mexico; hence the conclusions derived from these data should be considered as hypothesis for this population and other similar populations. The data correspond to an instrument of self-report; therefore, they might be different from those obtained by means of interviews, projective tests or reaction time tests.

In conclusion, regarding the first aim of this study, it is concluded that extreme open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons is present in a very low percentage of students, less than one percent. The proportion of total rejection (including extreme rejection) is also low, approximately one eighth. Therefore, most students will disapprove of situations in which the expression of blatant rejection is present. Nevertheless, from the evaluated factor of internalized homonegativity (one's own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity), the level of rejection was very high. Thus, in order to avoid drawing a false conclusion of acceptance, it becomes necessary to complement any evaluation of the attitude towards non-heterosexual persons with scales that assess open and subtle rejection.

Regarding the second aim of this study, it is concluded that a low level of open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons among these students is predicted by a higher level of acceptance of their own homosexual feelings, desires, and identity and by having non-heterosexual friends. Although relevant variables for predicting open rejection towards non-heterosexual persons were taken into account, the regression models explained low percentages of variance (less than one quarter of variance in the ordinal regression model and approximately one quarter in the multinomial regression model), accurately identifying the cases of acceptance, but showing low accuracy for the identification of the cases of rejection.

In future studies, evaluating both the open and the subtle aspects of rejection towards non-heterosexual persons is suggested. It is also recommended to consider as potential numerical predictive variables: sexual orientation (evaluated as a continuum through frequency of homosexual thoughts, feelings, desires, fantasies and behaviours), number of non-heterosexual friends, the attitude of the family of origin, religiosity, cognitive rigidity, dogmatism, and personality traits (openness and paranoia). These constructs should be assessed by means of scales in order to obtain numerical variables that will allow the application of parametric statistical analyses which use the full range of variances (linear multiple regression and path analysis). The inclusion of new numerical variables and the use of these parametric analyses will surely increase the percentage of explained variance.

In workshops intended to encourage the acceptance of sexual diversity, it may be useful and positive to deal with the issue of one's own homosexual feelings and the fear of showing non-accepted behaviours within the gender role, and to work with the experience of heterosexual individuals who have non-heterosexual friends. From the characteristics of friendly contact pointed out by Overby and Barth37, institutional authority figures should give support to positive contacts with non-heterosexual persons, including them as guests in the dynamics and discussions within these workshops. All of these activities would allow accepting, as a positive characteristic, any trait or behaviour that society might consider as homosexual. It is recommended that these workshops be carried out by teachers with training in pedagogical sexology and be coordinated by clinical psychologists or psychiatrists that could provide psychological advice and, if necessary, help participants achieve psychological containment.

Authors contributionsThe two authors designed the study and contributed with data collection, data analysis and redaction of this paper.

FundingThe research was funded by the authors.

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interests.

The authors thank Dr. Enrique Martinez for his support in the recruitment of participants, as well as the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of Tecnologico de Monterrey and the Faculty of Psychology of the Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon for their support in the development of this research.