Intravascular lymphoma (IVL) is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma characterized by occlusion of small vessels of organs by malignant cells with special tropism for the nervous system. Our purpose has been to describe a series of IVL diagnosed in our center and to compare the results with those of the literature.

MethodsA retrospective review of the clinical, imaging, and pathological data of consecutive patients with IVL in the last 20 years was performed. Pathology department database was the source of patient identification.

ResultsWe identified six cases (three males and three females), with a median age at diagnosis of 54.64 (interquartile range (IR) 51.93–59.67). Five of them (83.3%) debuted with neurological manifestations. The median time to diagnosis was 3.77 months. On cranial magnetic resonance imaging, the findings consisted of multiple white matter and corpus callosum lesions (some of them with enhancement or hemorrhagic foci) and multifocal infarcts with hemorrhagic transformation. One patient displayed leptomeningeal branch aneurysms. A proton emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (PET-FDG) was performed in five patients showing areas of elevated metabolism in all of them. Four patients underwent targeted biopsy, which allowed the diagnosis of IVL to be established in three. Four of the five patients who received treatment remained in complete remission with a median progression-free survival of 69.62 months (IR 49.11–162.82).

ConclusionsIVL begins frequently with neurological manifestations, which must alert the neurologist to be aware of this entity. PET-FDG helps to identify biopsy-accessible lesions and facilitate early diagnosis of IVL.

El linfoma intravascular (LIV) es un linfoma B difuso de células grandes caracterizado por la oclusión de los pequeños vasos de los órganos por las células malignas, y tiene un especial tropismo por el sistema nervioso. Nuestro objetivo ha sido describir una serie de LIV diagnosticados en nuestro centro y compararlos con los de la literatura.

MétodosSe realizó una revisión retrospectiva de los datos clínicos, de imagen y patológicos de una serie consecutiva de pacientes con LIV de los últimos 20 años. La identificación de los casos se obtuvo de las bases de datos del servicio de anatomía patológica.

ResultadosSe identificaron 6 pacientes (3 hombres y 3 mujeres) con una mediana de edad en el momento del diagnóstico de 54,64 años (rango intercuartílico [IR]: 51,93-59,67). Cinco (83,3%) comenzaron con manifestaciones neurológicas. La mediana de tiempo para establecer el diagnóstico de LIV fue de 3,77 meses. En la resonancia magnética craneal los hallazgos consistieron en múltiples lesiones de la sustancia blanca y del cuerpo calloso (algunas de ellas con captación de contraste y focos hemorrágicos), así como infartos multifocales con transformación hemorrágica. En un paciente se encontraron aneurismas en ramas leptomeníngeas. Se realizó tomografía por emisión de protones con fluorodeoxiglucosa (PET-FDG) a 5 pacientes, y en todos se encontraron áreas de elevada captación. Se realizó biopsia dirigida a dichas áreas a 4 pacientes que permitió establecer el diagnóstico en 3 de ellos. Cuatro de los 5 pacientes que recibieron tratamiento permanecen en remisión completa, con una mediana de tiempo libre de progresión de 69,62 meses (RI: 49,11-162,82).

ConclusionesEl LIV comienza con frecuencia con manifestaciones neurológicas, lo que debe alertar al neurólogo a tener presente esta entidad. La PET-FDG ayuda a identificar las lesiones accesibles para biopsia, y así facilitar su diagnóstico precoz.

Intravascular lymphoma (IVL) is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma characterized by occlusion of the small vessels of the affected organs by malignant cells.1 Its incidence is around one case per million inhabitants.2 Three variants of IVL are distinguished: the classic variant, which presents with fever and involvement of the central nervous system and skin; the cutaneous variant, which affects only the skin and has a better prognosis; and the hemophagocytic variant, which usually presents with hepatosplenic involvement and cytopenia. Neurological symptoms related to the involvement of the central nervous system have been commonly seen at diagnosis, occurring more frequently in European and American series of patients than in those coming from Asian countries.3

IVL represents a diagnostic challenge because its clinical presentation is very heterogeneous.1 The prognosis is poor, with a survival rate of less than 50% in the first three years, probably due to diagnostic delay.4,5 In fact, in the past, IVL was often diagnosed by autopsy, but the introduction of proton emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (PET-FDG) helps to identify regions with hypermetabolism, the biopsy of which allows the diagnosis to be established.6

Our purpose has been to describe the clinical, radiological, pathological manifestations and outcome of IVL in a series of patients diagnosed in our center in the last 20 years, to identify the factors influencing diagnostic delay and to compare the results of our series with those of the literature.

MethodsA retrospective review of the clinical, imaging, and pathological data of 6 consecutive patients with IVL over the last 20 years was performed in the University Hospital of Navarra (HUN). Patient identification was obtained from the Pathology department database. The following variables were recorded: age, sex, personal history, onset symptoms, neuroimaging and analytical findings, time from first symptoms to diagnosis, method of diagnosis, pathological findings, molecular characteristics of lymphoma, type of treatment and survival time. This information was obtained from review of the patients’ medical records and biopsy material. The Stata program version 16 was used to describe the variables in the sample and to analyze the factors influencing the time to diagnosis. Approval for the study was obtained from the medical research ethics committee of our center. The data from our series were compared with IVL series published in the literature, restricting the search to articles published in the last 20 years.

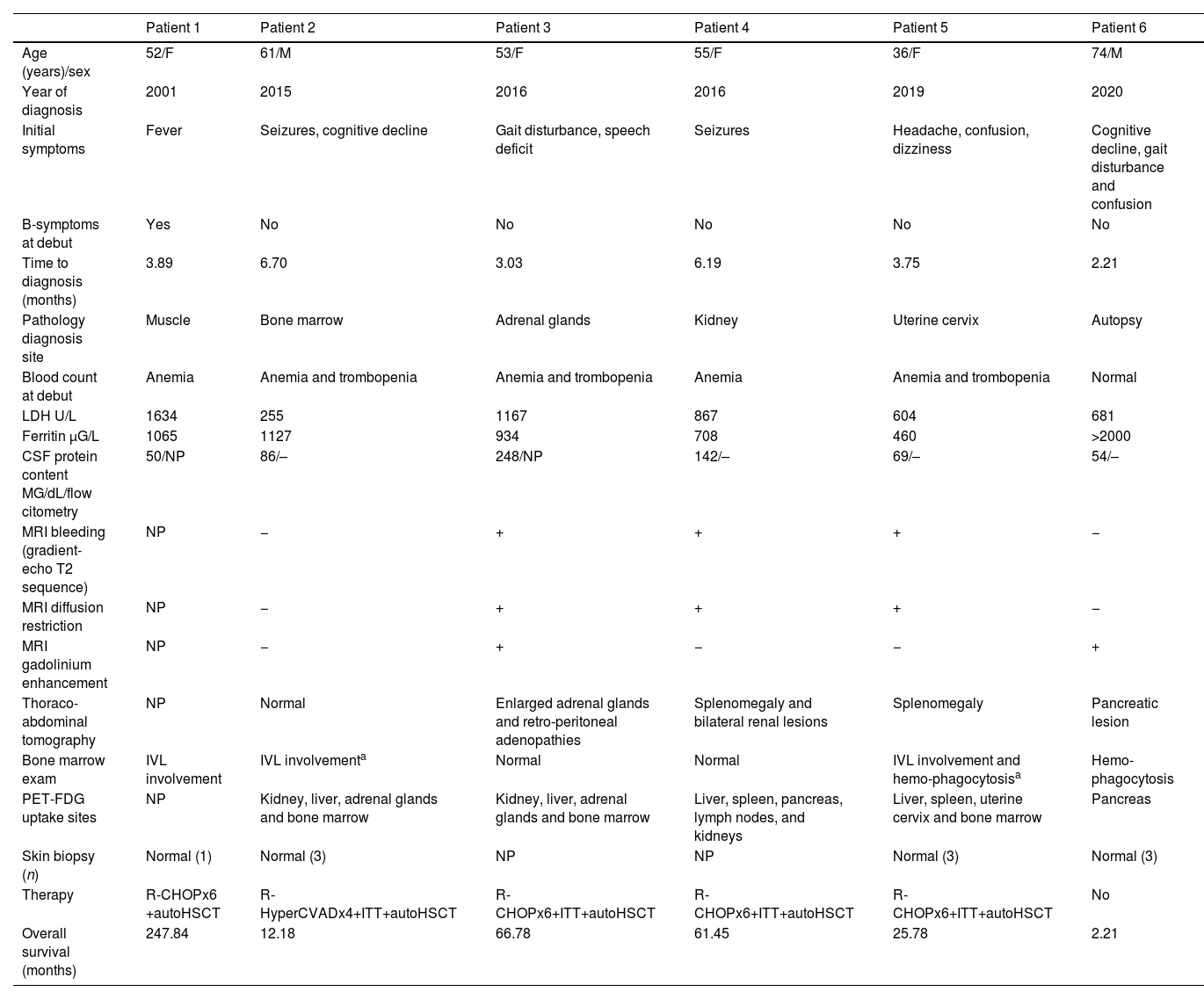

ResultsPatients and clinical manifestationsSix cases of IVL were found from 2000 to 2020, three males and three females, with a median age at diagnosis of 54.64 (interquartile range (IR) 51.93–59.67). Five of them (83.3%) debuted with neurological manifestations (Table 1) that were not accompanied by B symptoms, although at the time of diagnosis, three of them already had fever and sweating. Patients 2 and 4 had epileptic seizures. Patient 2 developed subsequently a mild and progressive cognitive decline. Patient 3 consulted for language impairment and gait disturbance, patient 5 presented headache, dizziness, and confusion, and patient 6 consulted for cognitive impairment. Patient 1 presented with fever of unknown origin and developed a cauda equina syndrome 3 months later. The neurophysiological study showed findings of axonal polyradiculoneuropathy.

Clinical and demographic data and results of complementary explorations.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)/sex | 52/F | 61/M | 53/F | 55/F | 36/F | 74/M |

| Year of diagnosis | 2001 | 2015 | 2016 | 2016 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Initial symptoms | Fever | Seizures, cognitive decline | Gait disturbance, speech deficit | Seizures | Headache, confusion, dizziness | Cognitive decline, gait disturbance and confusion |

| B-symptoms at debut | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Time to diagnosis (months) | 3.89 | 6.70 | 3.03 | 6.19 | 3.75 | 2.21 |

| Pathology diagnosis site | Muscle | Bone marrow | Adrenal glands | Kidney | Uterine cervix | Autopsy |

| Blood count at debut | Anemia | Anemia and trombopenia | Anemia and trombopenia | Anemia | Anemia and trombopenia | Normal |

| LDH U/L | 1634 | 255 | 1167 | 867 | 604 | 681 |

| Ferritin μG/L | 1065 | 1127 | 934 | 708 | 460 | >2000 |

| CSF protein content MG/dL/flow citometry | 50/NP | 86/– | 248/NP | 142/– | 69/– | 54/– |

| MRI bleeding (gradient-echo T2 sequence) | NP | − | + | + | + | − |

| MRI diffusion restriction | NP | − | + | + | + | − |

| MRI gadolinium enhancement | NP | − | + | − | − | + |

| Thoraco-abdominal tomography | NP | Normal | Enlarged adrenal glands and retro-peritoneal adenopathies | Splenomegaly and bilateral renal lesions | Splenomegaly | Pancreatic lesion |

| Bone marrow exam | IVL involvement | IVL involvementa | Normal | Normal | IVL involvement and hemo-phagocytosisa | Hemo-phagocytosis |

| PET-FDG uptake sites | NP | Kidney, liver, adrenal glands and bone marrow | Kidney, liver, adrenal glands and bone marrow | Liver, spleen, pancreas, lymph nodes, and kidneys | Liver, spleen, uterine cervix and bone marrow | Pancreas |

| Skin biopsy (n) | Normal (1) | Normal (3) | NP | NP | Normal (3) | Normal (3) |

| Therapy | R-CHOPx6 +autoHSCT | R-HyperCVADx4+ITT+autoHSCT | R-CHOPx6+ITT+autoHSCT | R-CHOPx6+ITT+autoHSCT | R-CHOPx6+ITT+autoHSCT | No |

| Overall survival (months) | 247.84 | 12.18 | 66.78 | 61.45 | 25.78 | 2.21 |

Auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; F, female; HyperCVAD, hyper fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; ITT, intratecal therapy; IVL, intravascular lymphoma; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; n, number of skin biopsies; NA, not available; NP, not performed; PET-FDG, proton emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone.

Findings of complementary explorations are summarized in Table 1. At the onset of symptoms, five patients had anemia, three of them had also thrombocytopenia; and none had leukopenia. At the time of diagnosis, patients 2, 4, and 5 had also leukopenia and hepatosplenic IVL infiltration demonstrated by PET-FDG uptake, patients 2 and 5 had also IVL infiltration in the coxal biopsy, patient 5 with hemophagocytosis. Patient 6 had marked hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, without IVL infiltration. All patients had elevated LDH and ferritin levels at the time of diagnosis as well as β2-microglobulin. Angiotensin-converting enzyme was elevated in patients 2 and 4. High interleukin 2 soluble receptor levels were found in the only patient (number 6) in whom it was determined. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed normal cell counts in all cases, with varying degrees of hyperproteinorrachia and the CSF flow cytometry was normal in the 4 patients that it was performed. Thoracoabdominal tomography was normal in one patient and showed varied visceral involvement in four. Bone marrow exam demonstrated the presence of IVL in 3 patients, 2 of whom had a previous normal exam performed one month earlier.

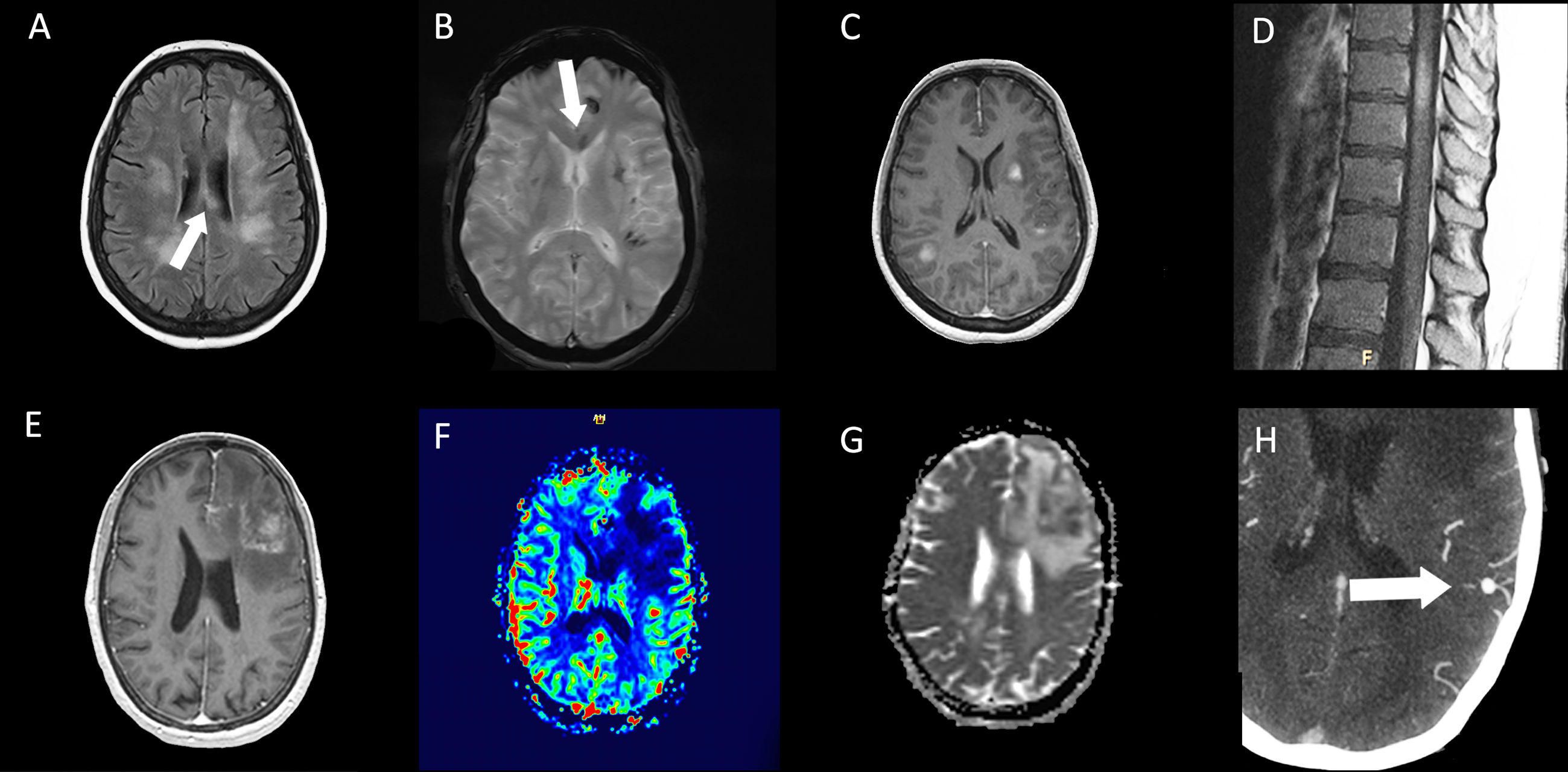

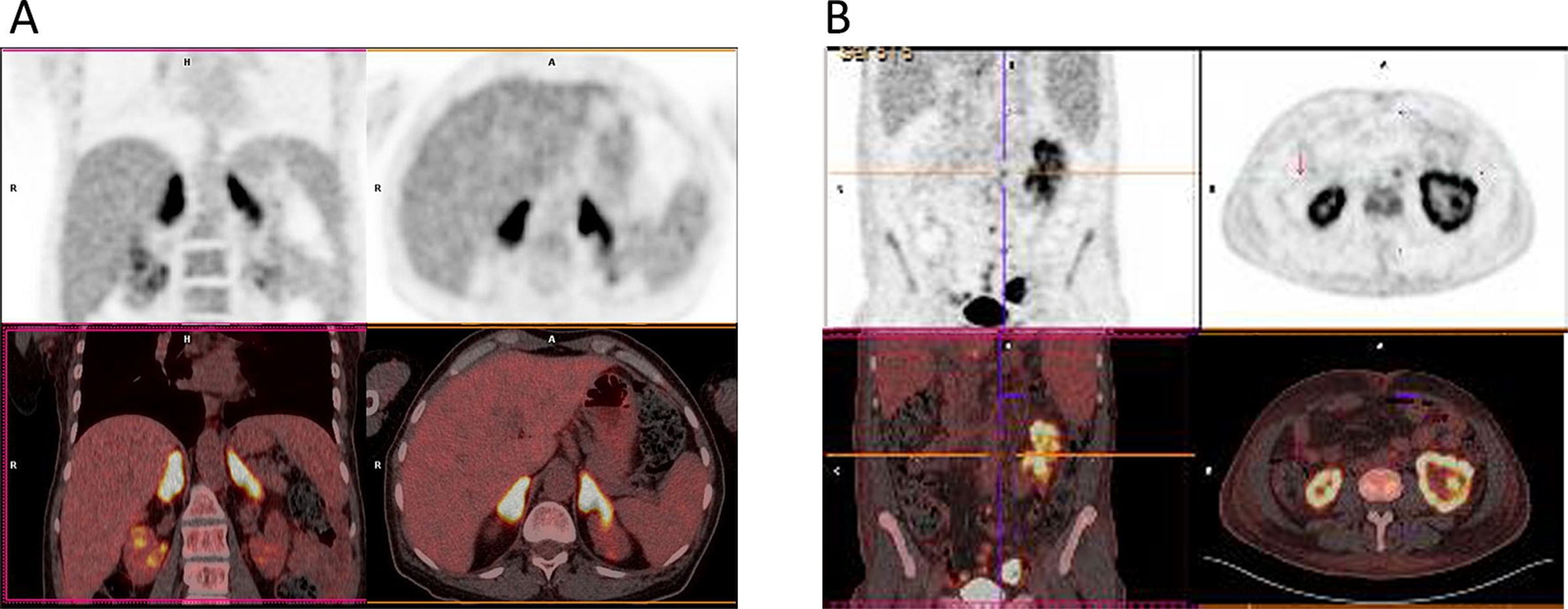

On cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1), the findings were (Table 1): multiple lesions in white matter and corpus callosum (some of them with enhancement and others with hemorrhagic foci) and multifocal infarcts with hemorrhagic transformation. Leptomeningeal branch aneurysms were found in patient 3. In two patients with spinal cord syndrome, the spinal cord MRI showed lesions with enhancement. A PET-FDG was performed in five patients showing various areas of elevated uptake in all of them (Fig. 2). Three patients underwent random skin biopsies, which were normal. In patient 1, the diagnosis was made by muscle biopsy. Targeted biopsy after PET-FDG findings was performed in four patients, which allowed the diagnosis of IVL to be established in three. One patient with pathological PET-FDG could not undergo solid organ biopsy because of severe thrombopenia and the diagnosis was established by coxal biopsy. One patient was diagnosed postmortem. In this last patient, a diagnosis was not reached despite pancreatic biopsy due to the fibrohematic content not suitable for analysis, although the suspicion of IVL had already been established during his lifetime.

Resonance imaging findings of two different patients. Patient 5 (top row): multiple hyperintense white matter lesions are shown in FLAIR image (A), with involvement of corpus callosum (arrows). Signs of hemorrhage on the gradient echo sequence (B) and enhancement after gadolinium injection in T1-weighted image (C) are present in some lesions. In dorsal spinal cord, an enhanced lesion is seen in a sagital T1-weighted image (D). Patient 3 (bottom row): A left frontal lesion with mass effect shows heterogeneous contrast enhancement in T1-weighted image (E). Lesion is hipovascular in perfusion sequence (F) and shows diffusion restriction in ADC map (G). Angio-CT image shows a left parietal leptomeningeal aneurism (thick arrow) (H).

Proton emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (PET-FDG) of two different patients. Patient 3 (A) PET-FDG (top row) and PET/computed tomography (CT) fusion (bottom row) showing focal increased uptake within adrenal glands. Patient 4 (B) PET-FDG (top row) and PET/CT fusion (bottom row) showing focal increased uptake within both kidneys, predominantly in the left.

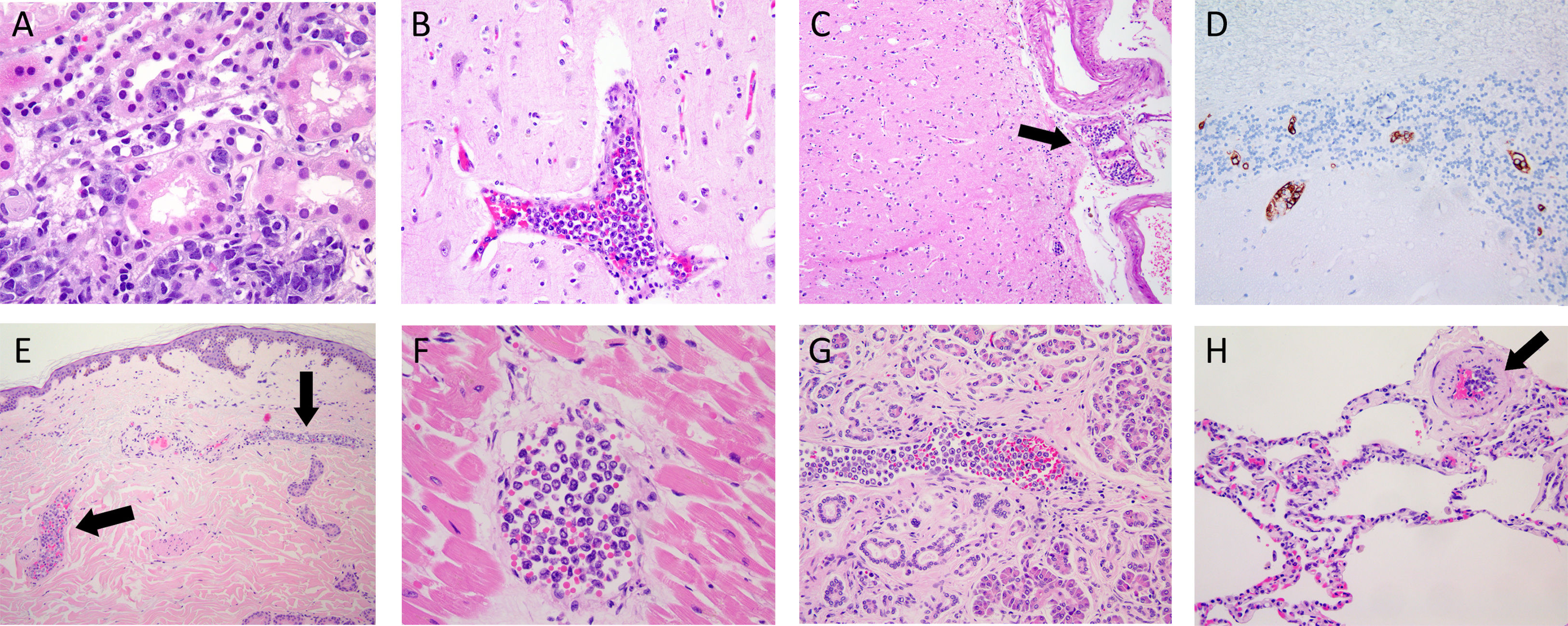

With respect to the pathological findings (Fig. 3), immunohistochemistry was performed in patients 2, 3, 4, and 5. The atypical cells had the following phenotype: CD20+, MUM1+, BCL2+, BCL6+ and C-MYC+. There were differences in CD-10; being positive just in patients 4 and 5. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of IVL B cell lymphoma.

Photomicrographs of different organs from two patients. (A) Kidney photomicrograph from biopsy of patient 4, showing atypical intravascular cells in blood vessels (H&E). (B-H) Photomicrographs of autopsy from patient 6. Cerebral tissue with occlusion of a cortex blood vessel (B) and a leptomeningeal arteriole (C, black arrow) (H&E). Cerebellar tissue showing positive staining with the CD20 antibody of intravascular cells (D). Intraluminal atypical lymphocytes within blood vessels of the dermis (E, black arrow), myocardium (F), pancreas (G) and lung (H, black arrow) (H&E).

The median time to diagnosis was 3.77 months (RI 2.99–5.076). According to the clinical classification made by the World Health Organization (WHO), four patients had the classical variant, and two patients were associated with hemophagocytosis phenomenon, all of them in stage IV-B.

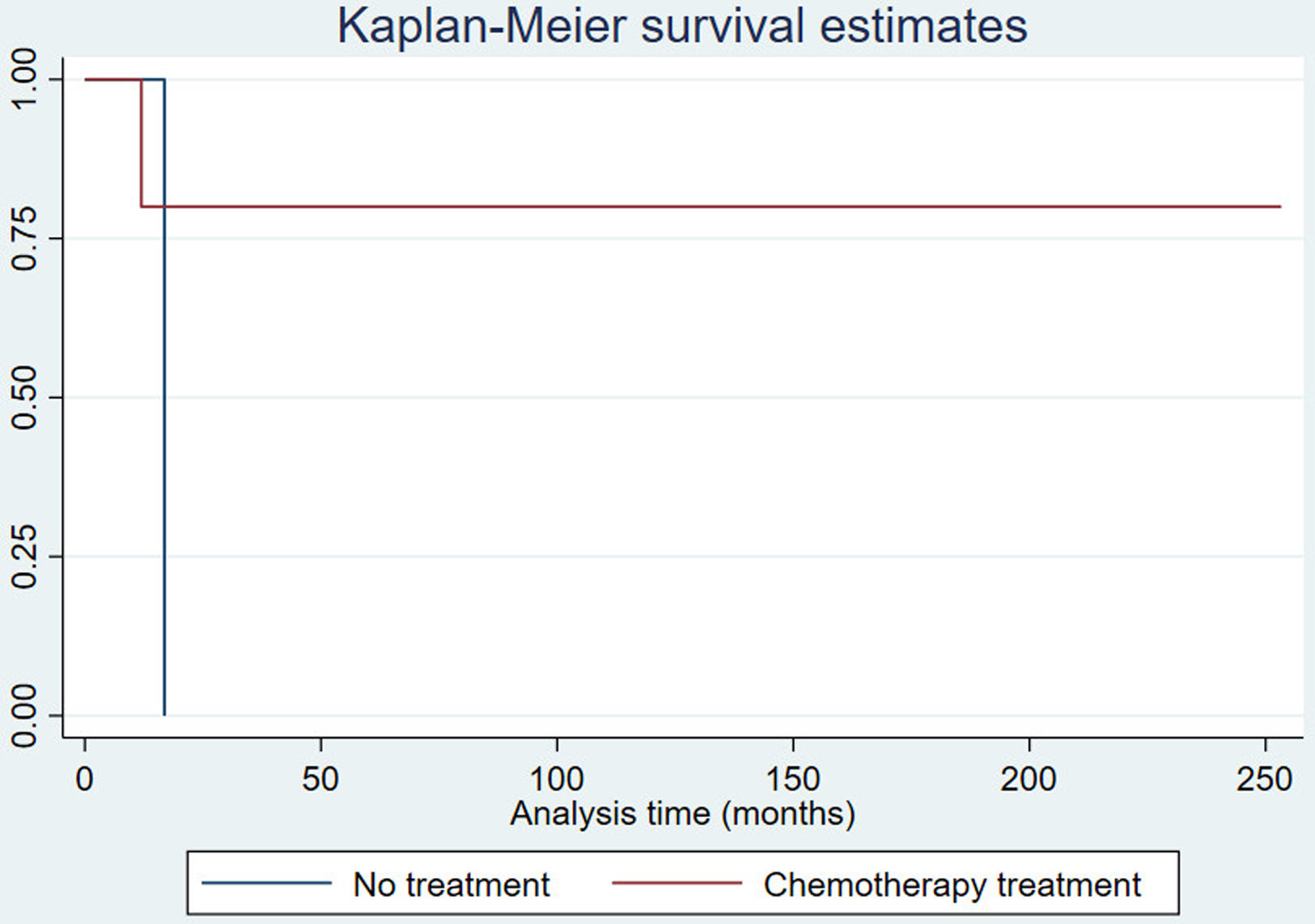

Treatment and evolutionChemotherapy treatment was administered in 4 patients with R-CHOP scheme (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and subsequent autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) and triple intrathecal therapy (TIT) (methotrexate, cytarabine, hydrocortisone) (except in patient 1). All remain in complete remission with a median progression-free survival of 69.62 months (RI 49.11–162.82) (Fig. 4). One patient was given four cycles of R-HyperCVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) with TIT and auto-HSCT; this patient died 12.18 months after the onset of symptoms owing to renal and hepatic failure. One patient received no treatment because the diagnosis was post mortem.

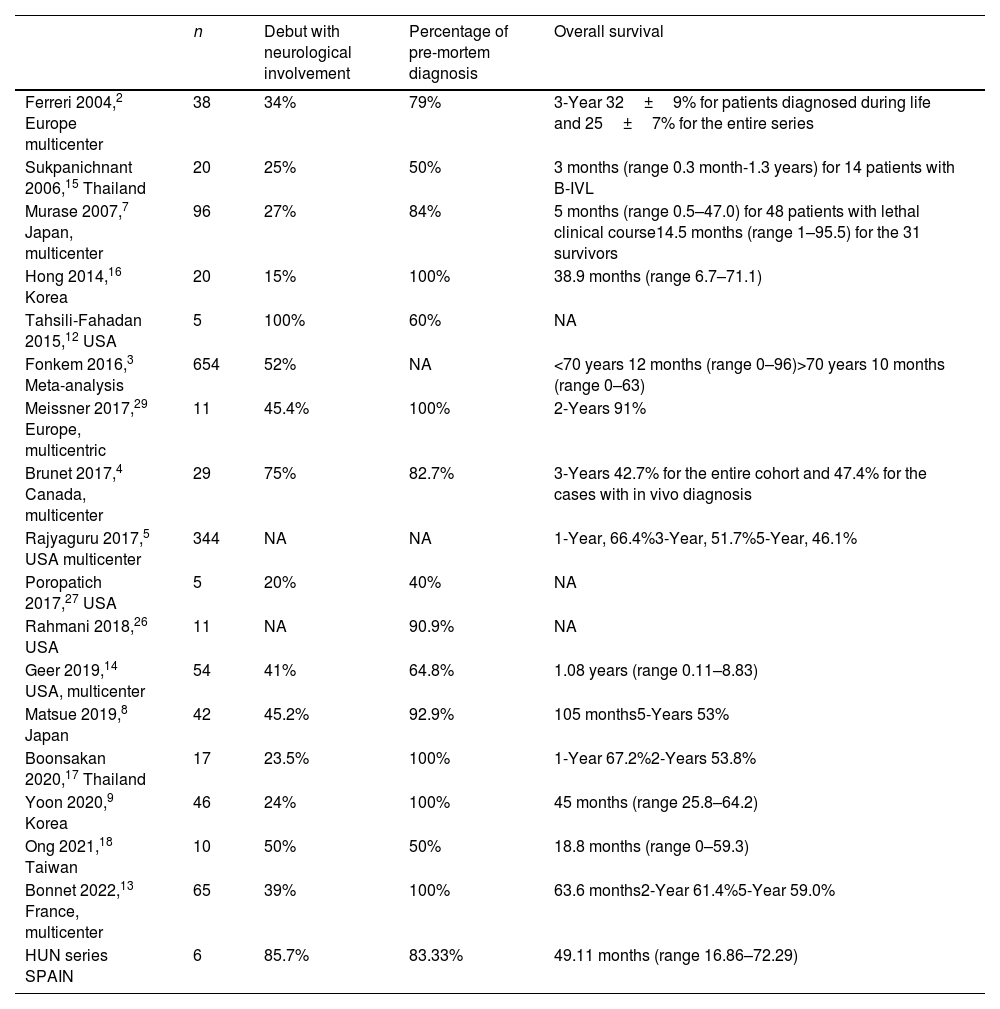

DiscussionWe describe here the clinical manifestations, neuroimaging findings, and outcomes of 6 patients with IVL from a single center. The largest published series of IVL are from Asian countries.7–9 In the prospective epidemiological registry on lymphomas conducted in Spain between 2014 and 2018, out of 9682 patients, only 8 cases with IVL have been included10 and to our knowledge, there is no published any Spanish hospital series of IVL.

The tropism of IVL for the nervous system implies that it often presents with neurological manifestations.3,11,12 The percentage of neurological involvement in our series (83.3% at presentation and 100% including all clinical courses) is higher than in those of the eastern series and resembles that of a Canadian multicenter study4 (Table 2). It has been recently published a French multicenter series of 65 patients in which neurological involvement was present in 39% of patients.13 CNS involvement by IVL in Western countries4,14 is superior to that described in Asian countries where multiorgan failure, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia and hemophagocytosis are the predominant manifestations.7,9,11,15–18 Five patients of our series debuted with heterogeneous neurological symptoms comprising epileptic seizures, cognitive impairment, headache, gait and speech disorders. One of the patients that debuted with fever developed subsequently a cauda equina syndrome. Mononeuropathy multiplex is the expected presentation when the peripheral nervous system is involved in IVL, but ascending cauda equina syndrome has also been reported in isolated case reports.19,20 Two patients of the present series presented spinal cord syndrome during the disease. Myelopathy caused by IVL is not exceptional and cases of longitudinally extensive myelopathy and spinal cord infarcts have been described.21,22

Summary of intravascular lymphoma series.

| n | Debut with neurological involvement | Percentage of pre-mortem diagnosis | Overall survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferreri 2004,2 Europe multicenter | 38 | 34% | 79% | 3-Year 32±9% for patients diagnosed during life and 25±7% for the entire series |

| Sukpanichnant 2006,15 Thailand | 20 | 25% | 50% | 3 months (range 0.3 month-1.3 years) for 14 patients with B-IVL |

| Murase 2007,7 Japan, multicenter | 96 | 27% | 84% | 5 months (range 0.5–47.0) for 48 patients with lethal clinical course14.5 months (range 1–95.5) for the 31 survivors |

| Hong 2014,16 Korea | 20 | 15% | 100% | 38.9 months (range 6.7–71.1) |

| Tahsili-Fahadan 2015,12 USA | 5 | 100% | 60% | NA |

| Fonkem 2016,3 Meta-analysis | 654 | 52% | NA | <70 years 12 months (range 0–96)>70 years 10 months (range 0–63) |

| Meissner 2017,29 Europe, multicentric | 11 | 45.4% | 100% | 2-Years 91% |

| Brunet 2017,4 Canada, multicenter | 29 | 75% | 82.7% | 3-Years 42.7% for the entire cohort and 47.4% for the cases with in vivo diagnosis |

| Rajyaguru 2017,5 USA multicenter | 344 | NA | NA | 1-Year, 66.4%3-Year, 51.7%5-Year, 46.1% |

| Poropatich 2017,27 USA | 5 | 20% | 40% | NA |

| Rahmani 2018,26 USA | 11 | NA | 90.9% | NA |

| Geer 2019,14 USA, multicenter | 54 | 41% | 64.8% | 1.08 years (range 0.11–8.83) |

| Matsue 2019,8 Japan | 42 | 45.2% | 92.9% | 105 months5-Years 53% |

| Boonsakan 2020,17 Thailand | 17 | 23.5% | 100% | 1-Year 67.2%2-Years 53.8% |

| Yoon 2020,9 Korea | 46 | 24% | 100% | 45 months (range 25.8–64.2) |

| Ong 2021,18 Taiwan | 10 | 50% | 50% | 18.8 months (range 0–59.3) |

| Bonnet 2022,13 France, multicenter | 65 | 39% | 100% | 63.6 months2-Year 61.4%5-Year 59.0% |

| HUN series SPAIN | 6 | 85.7% | 83.33% | 49.11 months (range 16.86–72.29) |

B-IVL, B intravascular lymphoma; NA, not available.

The heterogeneity of clinical manifestations and nonspecific laboratory and imaging findings make the diagnosis of IVL challenging. The difficulty in confirming the diagnosis in our series was due to these factors: B symptoms have often been absent at the debut of the disease, CSF showed only varying degrees of hyperproteinorrachy with normal flow cytometry, and brain MRI has shown alterations in the form of multiple corticosubcortical and white matter lesions, but not specific of a lymphoproliferative process.23 We have hardly found descriptions of cases with leptomeningeal aneurysms in relation to IVL as those found in one patient.24 It is important to note that all patients who underwent cranial MRI showed changes in the white matter and most of them in the corpus callosum. The finding of lesions with bleeding and enhancement has been frequent. Patients with IVL may show patterns of microhemorrhage and intravascular thrombosis on susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) sequences,25 which is a more sensible technique than gradient-echo T2 sequence, that was used in our series.

The appearance of cytopenia or splenomegaly alerted to the search for a hematologic disease, but it may happen that the first bone marrow exam does not show alterations and it may be necessary to repeat it, as has happened in two of the patients in our series.

The absence of a characteristic radiological pattern of systemic involvement, because by definition lymphomatous cells are confined to intravascular spaces, often without parenchymal involvement, adenopathy or space-occupying lesions, makes the diagnosis difficult. The PET-FDG allows the identification of areas with increased glucose metabolism, which helps to direct the biopsy to these organs.6 In our series, among the five cases in which PET-FDG was performed, a targeted biopsy allowed the diagnosis of IVL in three of them. It is not frequent to establish the diagnosis by muscle biopsy, as was the case in one patient of our series. In other western series2 the diagnosis was reached from skin biopsies of skin lesions, and in the eastern series7 from bone marrow biopsies and random skin biopsies. Skin biopsies in patients with the cutaneous variant have a very high diagnostic yield, but are less sensitive in patients with the classic variant and the one associated with hemophagocytosis, as has been the case in our series, in which random skin biopsy have not allowed to establish the diagnosis.

Of the 20 years analyzed in our study, 5 cases have been diagnosed in the last 10 years, suggesting that this entity has been underdiagnosed in the past.26 PET-FDG, a tool that has aided diagnosis, was not so widely available in the years prior to 2010. The median diagnostic delay in our series was 3.77 months and the percentage of diagnosis during life was 83.34%, higher than other recent series.18,27 Only one patient was diagnosed postmortem, being IVL a diagnostic suspicion in life, although the pancreatic biopsy did not provide useful material for analysis. This patient was an elderly man who suffered a rapid and progressive multiorgan deterioration that prevented the completion of the diagnostic study and therefore the treatment.

The median survival rate in our series was 49.11 months (RI 16.86–72.29), which increases to 69.62 months if we only consider patients who received treatment after diagnosis. This survival is similar to that reported in other studies (Table 2).

The patients in our series were mostly treated with the R-CHOP scheme and TIT followed by auto-HSCT as consolidation treatment. The addition of rituximab, an anti-CD-20 antibody, to conventional CHOP chemotherapy schedules has improved the survival of IVL, due to the presence of lymphomatous cells in the lumen of small vessels, where rituximab shows high bioavailability.28 Moreover, a retrospective multicenter study conducted by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, demonstrates that the results obtained with chemotherapy improve if auto-HSCT is used as consolidation treatment.29

Although our series is small and has the limitations of a retrospective study, it allows us to draw the following two conclusions: IVL begins frequently with neurological manifestations, which must alert the neurologist to be aware of this entity. In addition, PET-FDG helps to identify biopsy-accessible lesions, facilitating the early diagnosis of IVL, which in turn allows the initiation of appropriate treatment avoiding a fatal outcome.

Funding sources for studyThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities. MEE received a grant “Programa de intensificación” founded by “Departamento de Salud del gobierno de Navarra”.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.