Arterial dissection is a frequent cause of stroke in young patients, accounting for 20% of cases.1 It may present without symptoms, with headache or neck pain, or as severe stroke or subarachnoid haemorrhage.1–4 Dissection may occur in any segment of the vertebral artery, with V2 being the most frequent (34%).5 The consequences of dissection may depend on such factors as localisation, the degree of obstruction, and collateral status.

Brachial plexus block is a regional anaesthetic technique that may be performed via a supraclavicular, infraclavicular, or axillary approach; it is used in surgery and for the treatment of postoperative pain in the upper limb.

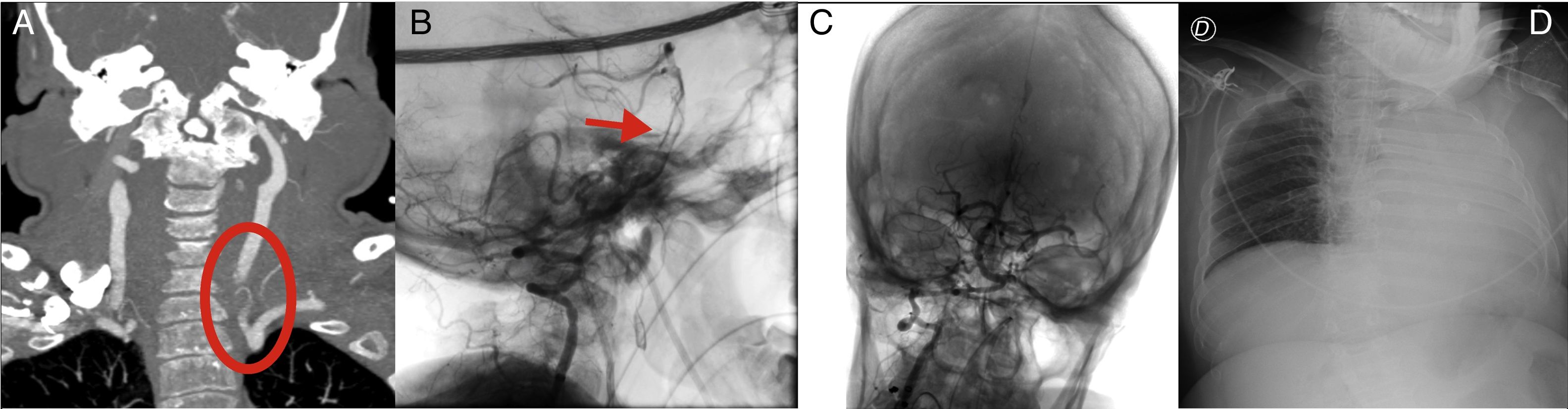

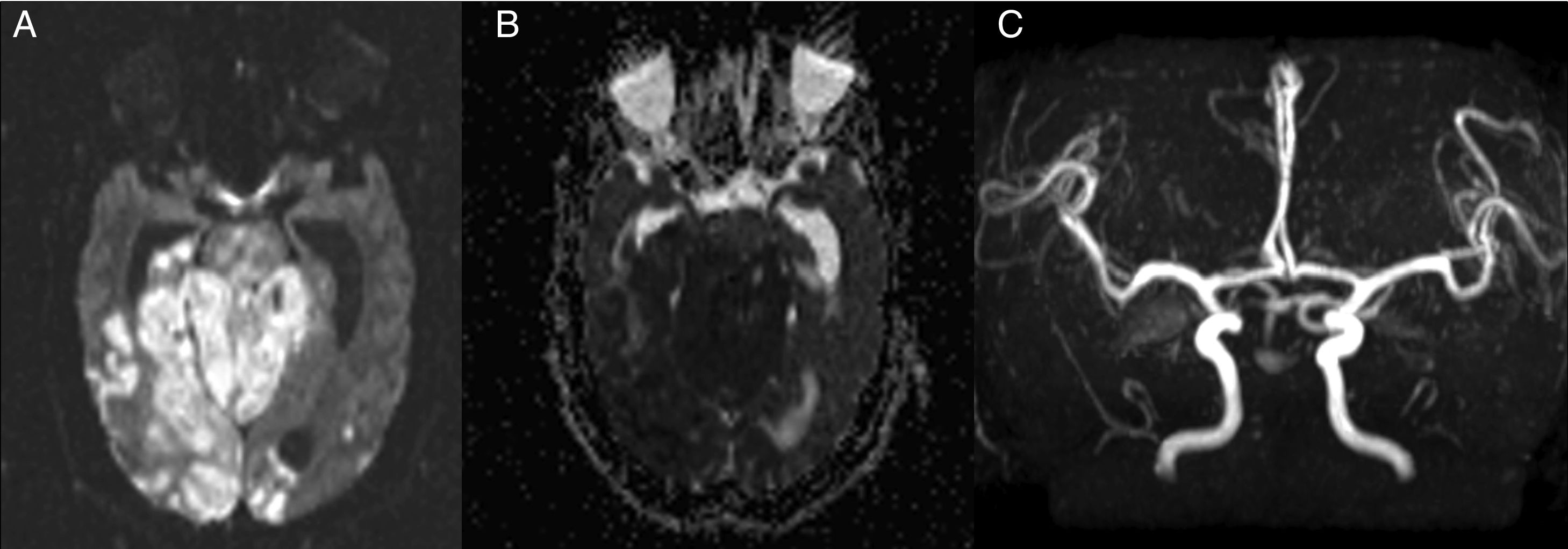

We present the case of a 47-year-old woman with history of achondroplasia and carpal tunnel syndrome, which was treated surgically. The procedure included regional anaesthetic block of the brachial plexus via a supraclavicular approach. Following the procedure, the patient reported supraclavicular and posterior neck pain; 24 hours later, she presented sudden-onset symptoms of dizziness, bilateral tinnitus, hypoacusia, and headache; subsequently, her level of consciousness decreased towards a coma state (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3), requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. A blood analysis revealed respiratory acidosis and the electrocardiography showed sinus rhythm. A chest radiography revealed left hemithorax opacification following one-lung ventilation (Fig. 1D). A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral subarachnoid haemorrhage in the sulci of the frontal convexity and the fourth ventricle, with no acute ischaemic lesions; a CT angiography study confirmed the proximal dissection of the left vertebral artery, with basilar artery thrombosis (Fig. 1A). In the acute phase, we performed endovascular mechanical thrombectomy to treat the basilar artery thrombosis within 2 hours of onset, achieving complete recanalisation (TICI grade 3) (Fig. 1B and C). A follow-up brain MRI scan performed at 24 hours showed an extensive ischaemic lesion in the basilar artery territory, as well as signs of hydrocephalus. MRI angiography confirmed basilar rethrombosis (Fig. 2). At 48 hours of admission, the patient died.

(A) Coronal CT angiography slice showing the origin of the left vertebral artery and its narrowing, which confirms arterial dissection. (B) Angiography with lateral projection confirming thrombosis of the distal third of the basilar artery. (C) Angiography with frontal projection following mechanical thrombectomy, displaying complete recanalisation. (D) Chest radiography with the patient in the supine position, revealing left hemithorax opacification.

MRI and MRI angiography studies. (A and B) Axial DWI and ADC sequences, respectively, revealing extensive acute ischaemic stroke involving the pons, cerebellum, and bilateral occipital region. (C) MRI angiography sequence showing absence of blood flow in the basilar artery, confirming rethrombosis.

Arterial dissection is a known cause of ischaemic stroke, accounting for 2% of cases.2 Eighty percent of arterial dissections affect the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries.6,7 Neck trauma and connective tissue diseases are associated causes. Angiography has traditionally been the technique of choice for diagnosing arterial dissections; however, advances in non-invasive neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI angiography and CT angiography, as well as the increasing use of Doppler ultrasound, enable sensitive, accurate diagnosis of arterial dissections, detecting both intramural haematoma and decreased arterial lumen.8

The posterior triangle of the neck has numerous vascular structures, and multiple anatomical variants should be considered when performing invasive procedures, such as brachial plexus block.9 Knowledge of the anatomical structures and the use of complementary techniques enable us to perform the anaesthetic procedure more accurately, while decreasing the risk of vascular complications.10 In our case, knowledge of anatomy and the individual circumstances of the patient due to the baseline condition, as well as the performance of ultrasound-guided anaesthetic block, may minimise the potentially fatal adverse effects.

Please cite this article as: Montejo C, Vicente M, Sánchez A, Renú A. Trombosis basilar por disección vertebral secundaria a bloqueo del plexo braquial. Neurología. 2020;35:56–58.