The diagnostic paradigm of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is changing; there is a trend toward diagnosing the disease in its early stages, even before the complete syndrome of dementia is apparent. The clinical stage at which AD is usually diagnosed in our area is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to describe the clinical stages of AD patients at time of diagnosis.

MethodsMulticentre, observational and cross-sectional study. Patients with probable AD according to NINCDS-ARDRA criteria, attended in specialist clinics in Spain, were included in the study. We recorded the symptom onset to evaluation and symptom onset to diagnosis intervals and clinical status of AD (based on MMSE, NPI questionnaire, and CDR scale).

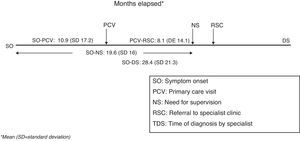

ResultsParticipants in this study included 437 specialists representing all of Spain's autonomous communities and a total of 1707 patients, of whom 1694 were included in the analysis. Mean MMSE score was 17.6±4.8 (95% CI: 17.4–17.9). Moderate cognitive impairment (MMSE between 10 and 20) was detected in 64% of the patients, and severe cognitive impairment (MMSE <10) in 6%. The mean interval between symptom onset and the initial primary care visit was 10.9±17.2 months (95% CI: 9.9–11.8), and the interval between symptom onset and diagnosis with AD was 28.4±21.3 months.

ConclusionsResults from the EACE show that most AD patients in our area have reached a moderate clinical stage by the time they are evaluated in a specialist clinic.

Estamos asistiendo a un cambio en el paradigma del diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA), de modo que tiende a realizarse en fases más precoces de la evolución, incluso antes de la aparición del síndrome completo de demencia. En nuestro entorno no se conoce en qué situación clínica se está realizando el diagnóstico de la EA. Por ese motivo, se ha llevado a cabo este estudio, para describir el estadio evolutivo de los pacientes con EA en el momento del diagnóstico.

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico, observacional y transversal. Se incluyeron pacientes que cumplían criterios NINCDS-ARDRA de EA probable, atendidos en consultas de Atención Especializada en España. Se recogieron los datos sobre los tiempos asistenciales y de evolución de la EA según el MMSE, el cuestionario NPI y la escala CDR.

ResultadosParticiparon 437 especialistas de todas las Comunidades Autónomas, que incluyeron un total de 1.707 pacientes, de los cuales 1.694 fueron incluidos en el análisis. La puntuación media del MMSE fue de 17,6±4,8 (IC 95%: 17,4-17,9). El 64% de los pacientes presentaban deterioro cognitivo moderado (MMSE entre 10 y 20) y el 6% grave (MMSE<10). El tiempo medio desde los primeros síntomas hasta la primera consulta a Atención Primaria fue de 10,9±17,2 meses (IC 95%: 9,9-11,8), y hasta el diagnóstico de la EA fue de 28,4±21,3 meses.

ConclusionesLos resultados del EACE ponen de manifiesto que en nuestro entorno la mayor parte de los pacientes con EA acuden a Atención especializada en un estado evolutivo moderado.

The Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN) defines dementia as an acquired, persistent alteration in brain function that affects at least 2 cognitive spheres (memory, language, visuospatial function, executive functions, behaviour) to such an extent as to interfere with a person's daily activities without there being a change in his level of consciousness.1 This condition affects 4% of the population aged 60 and over worldwide, with few regional differences, although overall prevalence is higher in developed countries. Generally speaking, more than two-thirds of all subjects with dementia will be diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease (AD).2

Current treatments for AD have shown statistically significant levels of efficacy for improving cognitive function and almost all clinical manifestations of this condition. They are also cost-effective and improve patient and carer quality of life. Available guidelines therefore recommend beginning drug treatments as soon as AD is diagnosed.1,3,4 Nonetheless, this type of disorder often has insidious initial manifestations that make it difficult to distinguish from other entities. As a result, diagnosing AD in its earliest stages may be challenging.5 Late diagnosis of AD is accompanied by a late start for the specific drug treatment. However, mounting evidence shows that early treatment may optimise therapeutic benefits and delay cognitive decline.6 Doctors have therefore proposed initiatives for identifying the disease in its initial stages.7,8 In fact, in the area of AD studies, proposals to change AD diagnostic criteria in order to achieve early diagnosis have had considerable impact.9–14 Although it is commonly believed that cases are diagnosed in relatively advanced stages in clinical practice, we should stress that there is no reliable information about when AD is diagnosed in Spain. We proposed conducting EACE, a study of AD in specialist clinics, in order to collect this information. Its purpose was to describe patients’ stage of AD at the time of diagnosis in Spain, in specialist clinics able to indicate specific treatment for AD.

Patients and methodsEACE is a multi-centre, observational cross-sectional study performed in Spanish specialist care clinics. The main purpose of the study is to describe the developmental stage at which patients with AD are referred to a specialist care centre for diagnosis. We also measure the time to provide care. Since the study is observational, it includes no clinical interventions.

The study was carried out by specialists in each of Spain's autonomous communities in which doctors consented to participate. Each specialist was asked to include the first 4 patients seen in the office or clinic between May and November 2009, with the following selection criteria: meeting NINCDS-ARDRA criteria for probable AD15 at that time and with no prior diagnosis of the disease; being able to take neuropsychological tests; and having a reliable informant who would be able to answer the study questions. It was assumed that patients who had previously been treated with specific drugs had already been diagnosed. They were excluded from the study, as were patients whose dementia stemmed from other causes (Parkinson's disease, hydrocephalus, stroke). Patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study according to good medical practice framework and the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at Hospital General Universitario, Elche.

Data were recorded in a single visit by the appropriate professional. The following variables were recorded for each case.

- 1.

Sociodemographic variables: age, sex, education (years and level, classifying subjects as illiterate, functionally illiterate, primary studies, secondary studies, and higher education), household composition at symptom onset, and relationship with primary carer.

- 2.

Family history, comorbidities, and concomitant treatments.

- 3.

Clinic data: specialty referring the patient, specialty treating the patient, clinic location, clinic organisational level (general outpatient clinic, general or specific hospital department, dementia unit, other) and geographical data/demographics (location and city size, broken down as more than 500000, 100000 to 500000, and fewer than 100000 inhabitants.

- 4.

Initial symptom of disease (impaired memory, language, behaviour, recognition, other).

- 5.

Retrospective data for disease progression:

- •

Estimated date of symptom onset.

- •

Date of first visit.

- •

Date patient was referred to specialist.

- •

Estimated date of when patient started needing supervision.

- •

Date the specialist completed evaluation (diagnosis and inclusion in the study).

- •

Reasons for any delays in referral.

- •

- 6.

Description of the patient's cognitive, behavioural, and overall status, using:

We estimated a sample size of 1600 cases in order to obtain valid estimates for scores on the scales listed above. We assumed a precision error at or below 25% and a 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) in a conservative scenario with a loss to follow-up of 5%. We analysed all patients who were included and met selection criteria. The sample was described with measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables, with their corresponding CI 95%. We also completed bivariate analyses to explore certain subgroups. Quantitative variables were evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; variables not meeting criteria for a normal distribution were measured using non-parametric methods. Statistical tests were bilateral and they employed a 5% significance level. SAS® software version 8.2 was used to complete all statistical analyses.

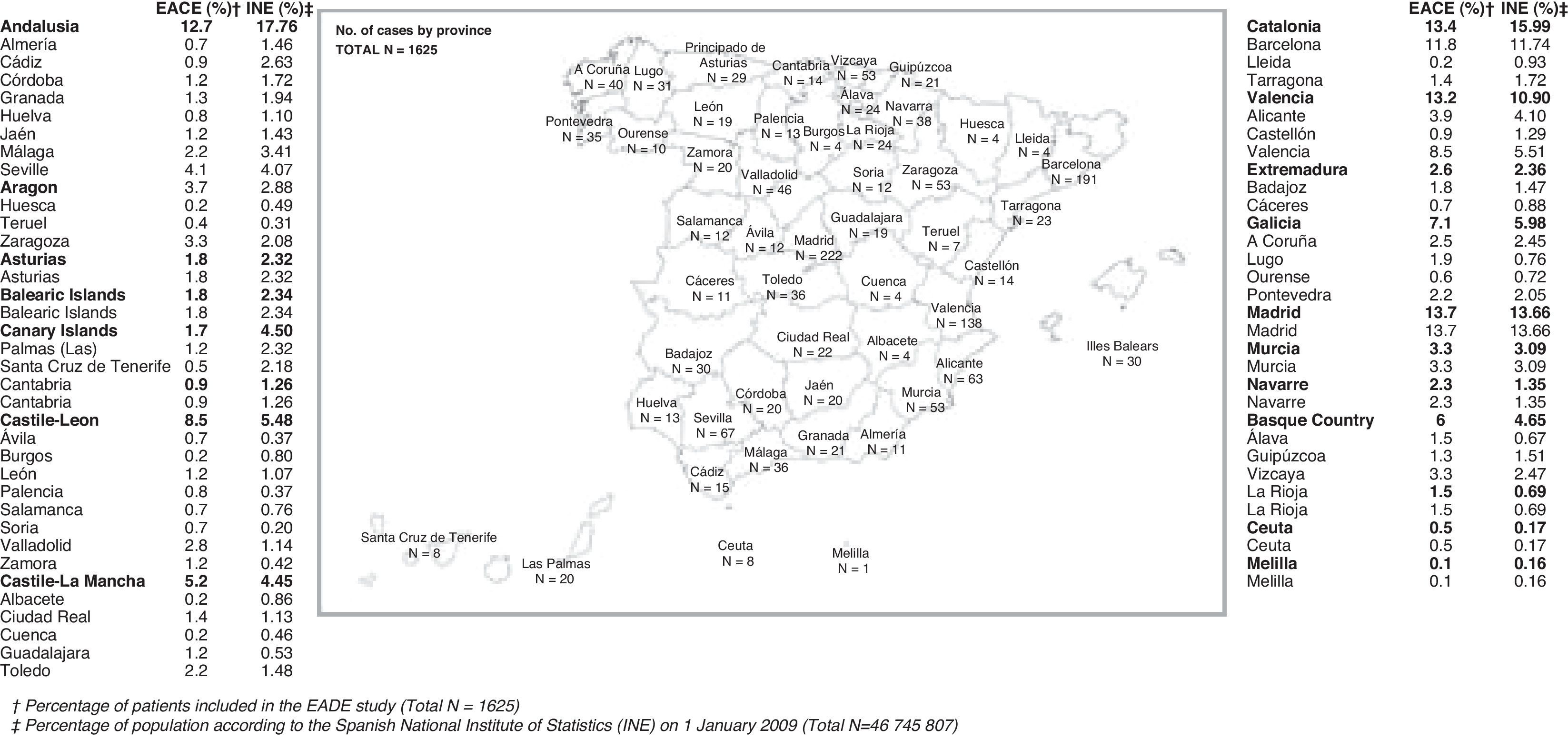

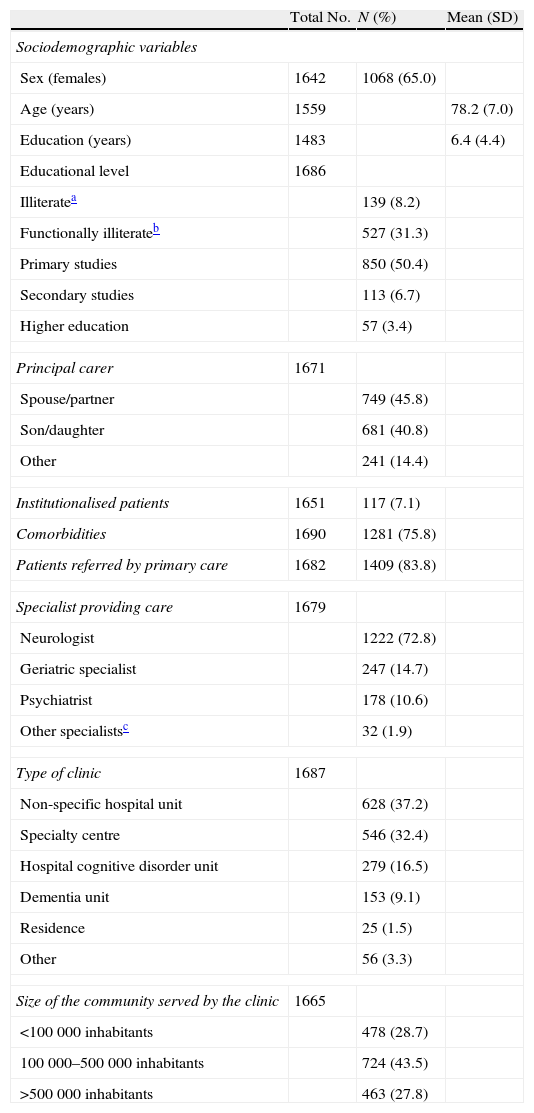

ResultsGeneral characteristicsOf the 1707 patients included in the study, we evaluated the 1694 who met eligibility criteria. Patients’ data were gathered by 437 professionals representing all of Spain's autonomous communities, as shown in Fig. 1. This study is approximately representative of the general population, with certain deviations; for example, Andalusia and the Canary Islands are somewhat under-represented.

The general characteristics of the sample are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. Noteworthy characteristics in this sample include that nearly 40% of subjects were categorised as illiterate or functionally illiterate; care being mostly provided by neurologists; and the discrete representation of specialist clinics and dementia units.

Sample characteristics.

| Total No. | N (%) | Mean (SD) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Sex (females) | 1642 | 1068 (65.0) | |

| Age (years) | 1559 | 78.2 (7.0) | |

| Education (years) | 1483 | 6.4 (4.4) | |

| Educational level | 1686 | ||

| Illiteratea | 139 (8.2) | ||

| Functionally illiterateb | 527 (31.3) | ||

| Primary studies | 850 (50.4) | ||

| Secondary studies | 113 (6.7) | ||

| Higher education | 57 (3.4) | ||

| Principal carer | 1671 | ||

| Spouse/partner | 749 (45.8) | ||

| Son/daughter | 681 (40.8) | ||

| Other | 241 (14.4) | ||

| Institutionalised patients | 1651 | 117 (7.1) | |

| Comorbidities | 1690 | 1281 (75.8) | |

| Patients referred by primary care | 1682 | 1409 (83.8) | |

| Specialist providing care | 1679 | ||

| Neurologist | 1222 (72.8) | ||

| Geriatric specialist | 247 (14.7) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 178 (10.6) | ||

| Other specialistsc | 32 (1.9) | ||

| Type of clinic | 1687 | ||

| Non-specific hospital unit | 628 (37.2) | ||

| Specialty centre | 546 (32.4) | ||

| Hospital cognitive disorder unit | 279 (16.5) | ||

| Dementia unit | 153 (9.1) | ||

| Residence | 25 (1.5) | ||

| Other | 56 (3.3) | ||

| Size of the community served by the clinic | 1665 | ||

| <100000 inhabitants | 478 (28.7) | ||

| 100000–500000 inhabitants | 724 (43.5) | ||

| >500000 inhabitants | 463 (27.8) | ||

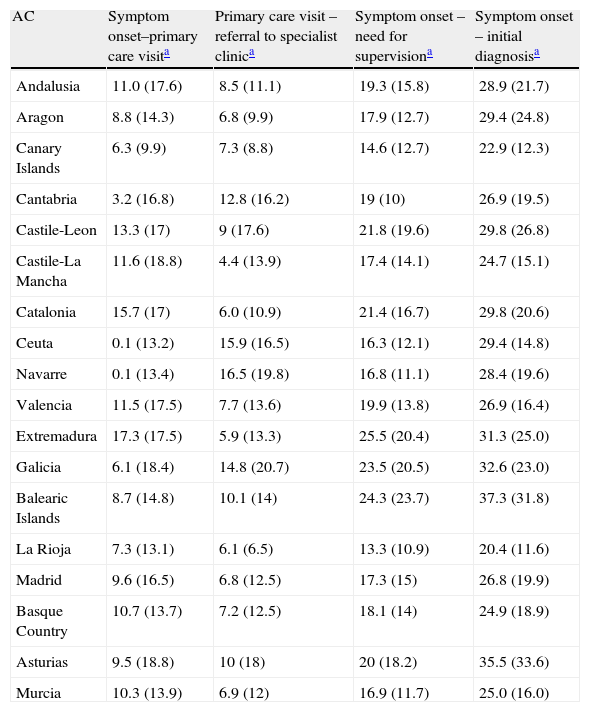

Time to provide care: breakdown by Spanish autonomous community (AC).

| AC | Symptom onset–primary care visita | Primary care visit – referral to specialist clinica | Symptom onset – need for supervisiona | Symptom onset – initial diagnosisa |

| Andalusia | 11.0 (17.6) | 8.5 (11.1) | 19.3 (15.8) | 28.9 (21.7) |

| Aragon | 8.8 (14.3) | 6.8 (9.9) | 17.9 (12.7) | 29.4 (24.8) |

| Canary Islands | 6.3 (9.9) | 7.3 (8.8) | 14.6 (12.7) | 22.9 (12.3) |

| Cantabria | 3.2 (16.8) | 12.8 (16.2) | 19 (10) | 26.9 (19.5) |

| Castile-Leon | 13.3 (17) | 9 (17.6) | 21.8 (19.6) | 29.8 (26.8) |

| Castile-La Mancha | 11.6 (18.8) | 4.4 (13.9) | 17.4 (14.1) | 24.7 (15.1) |

| Catalonia | 15.7 (17) | 6.0 (10.9) | 21.4 (16.7) | 29.8 (20.6) |

| Ceuta | 0.1 (13.2) | 15.9 (16.5) | 16.3 (12.1) | 29.4 (14.8) |

| Navarre | 0.1 (13.4) | 16.5 (19.8) | 16.8 (11.1) | 28.4 (19.6) |

| Valencia | 11.5 (17.5) | 7.7 (13.6) | 19.9 (13.8) | 26.9 (16.4) |

| Extremadura | 17.3 (17.5) | 5.9 (13.3) | 25.5 (20.4) | 31.3 (25.0) |

| Galicia | 6.1 (18.4) | 14.8 (20.7) | 23.5 (20.5) | 32.6 (23.0) |

| Balearic Islands | 8.7 (14.8) | 10.1 (14) | 24.3 (23.7) | 37.3 (31.8) |

| La Rioja | 7.3 (13.1) | 6.1 (6.5) | 13.3 (10.9) | 20.4 (11.6) |

| Madrid | 9.6 (16.5) | 6.8 (12.5) | 17.3 (15) | 26.8 (19.9) |

| Basque Country | 10.7 (13.7) | 7.2 (12.5) | 18.1 (14) | 24.9 (18.9) |

| Asturias | 9.5 (18.8) | 10 (18) | 20 (18.2) | 35.5 (33.6) |

| Murcia | 10.3 (13.9) | 6.9 (12) | 16.9 (11.7) | 25.0 (16.0) |

The mean MMSE score for the sample was 17.6±4.8 (95% CI: 17.4–17.9), with the following distribution: mild (score >20) 30%, moderate (score 10–20) 64%, and severe (score <10) 6%. The mean value of the test version adjusted by age and education was 19.1±4.7 (CI 95%: 18.8–19.3).

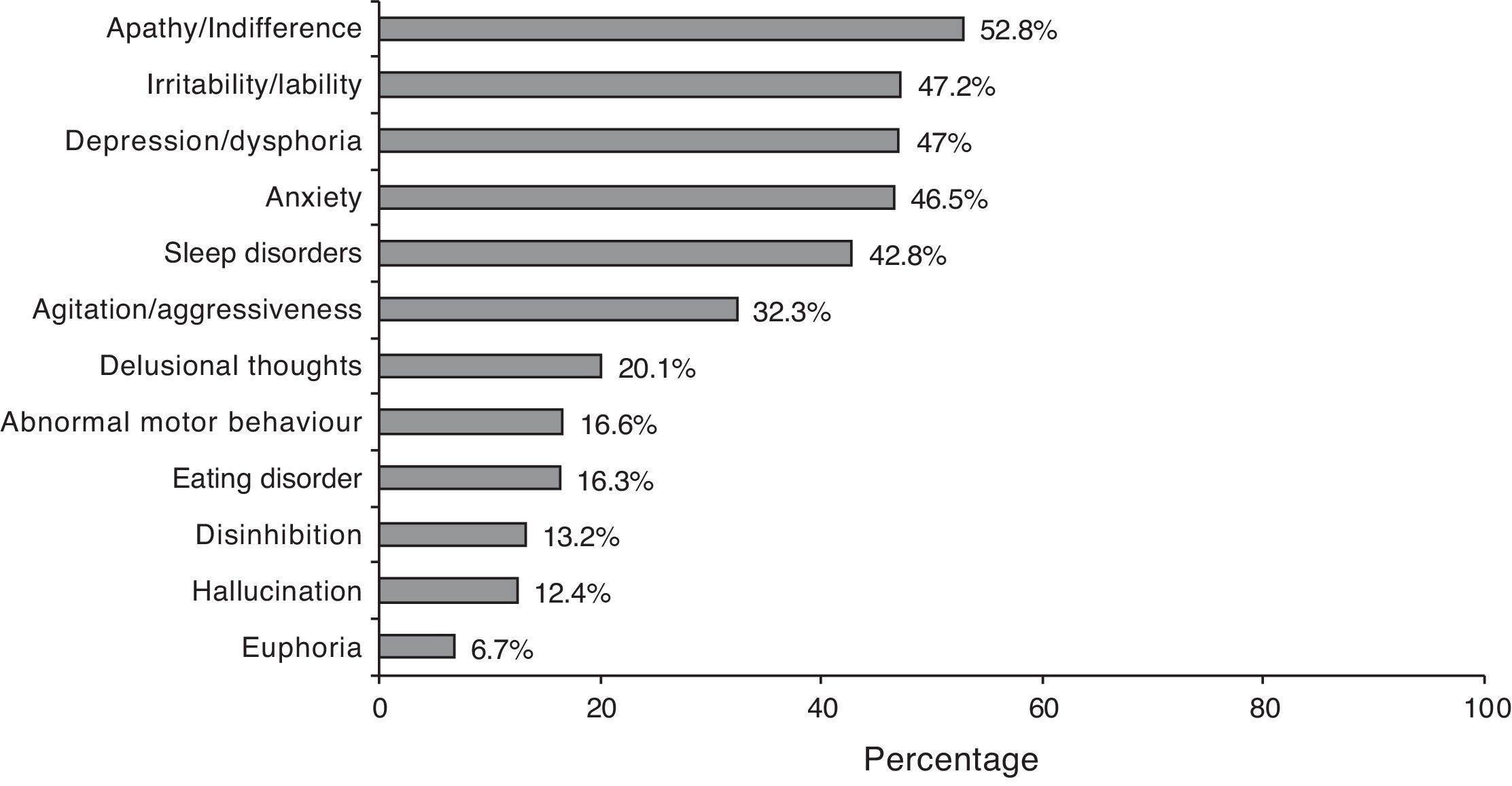

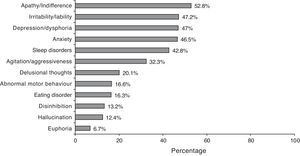

According to the NPI description, 87.5% of the cases presented a neuropsychiatric symptom. Symptom frequencies are shown in Fig. 2. The mean total score on the NPI scale was 12.3±13.2, which shows considerable dispersion (CI 95%: 11.6–13.0).

The CDR scale was used to assess the degree of dementia with the following results: possible dementia in 18%, mild dementia in 52%, moderate dementia in 25%, and severe dementia in 4.

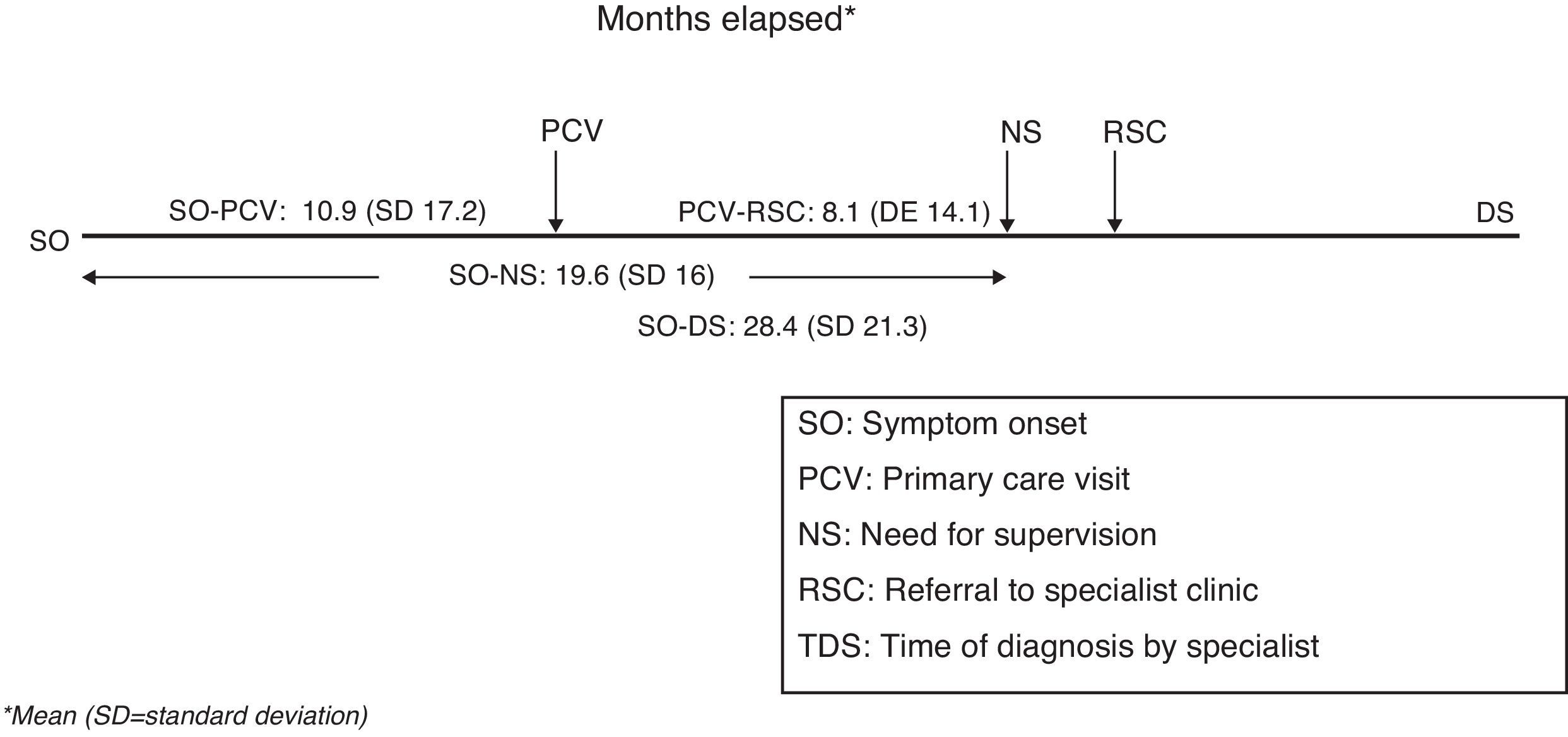

The mean time elapsed between initial symptoms and the first primary care visit (symptom onset – PC visit) was estimated at 10.9±17.2 months (CI 95%: 9.9–11.8). Mean time between the first primary care visit and receiving a referral to specialist care (PC visit – referral specialist) was 8.1±14.1 months (CI 95%: 7.3–8.8). The time between initial symptoms and time of diagnosis (symptom onset – specialist diagnosis), which did not necessarily coincide with the first visit to the specialist, was 28.4±21.3 months. Progression time prior to needing supervision (symptom onset – need for supervision) was 19.6±16 months (CI 95%: 18.8–20.4). All time variables are shown in Fig. 3. The different time-to-care measurements expressed with standard deviations demonstrate sizeable dispersion both within and between autonomous communities (Table 2). Time-to-care measurements were taken from the data collected according to the study protocol: date of inclusion, date of first PC visit, date of referral to specialist, and an estimated date of symptom duration based on the medical history.

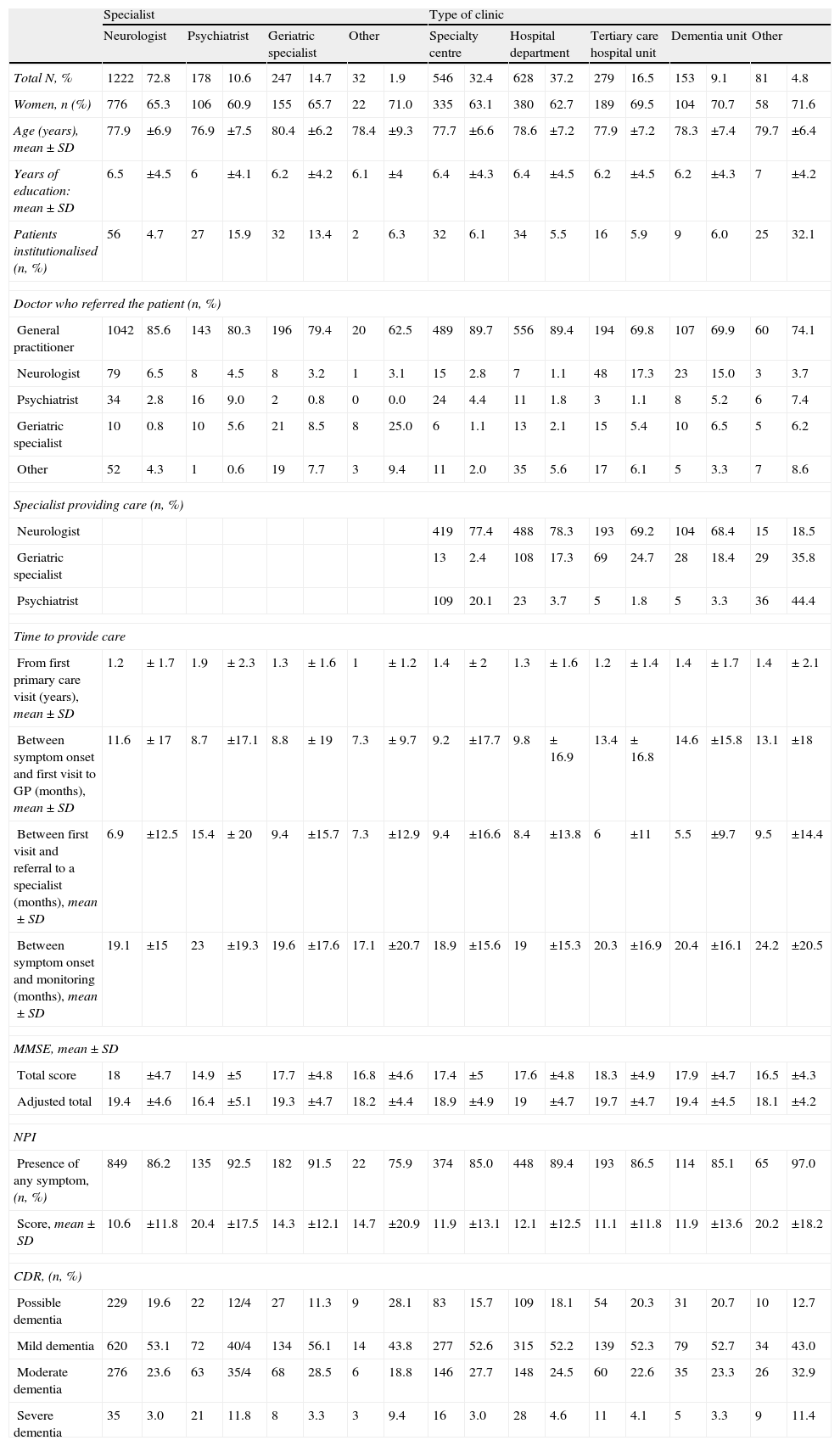

Secondary analysesThe results from comparisons of general patient characteristics and their condition at the time of diagnosis, based on pre-established variables, are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Table 3 presents comparisons of social characteristics, such as presence/absence of institutionalisation, patient's relationship with carer, and the size of the town in which care was provided. Table 4 presents comparisons of care characteristics, such as type of specialist and type of clinic providing care.

Comparison of subgroups broken down by social characteristics.

| Institutionalised | With carer | Municipality (No. inhabitants) | ||||||||||||

| No | Yes | Spouse/partner | Daughter/son | <100000 | 100000–500000 | >500000 | ||||||||

| Total N, % | 1534 | 92.9 | 117 | 7.1 | 749 | 52.4 | 681 | 47.6 | 478 | 28.7 | 724 | 43.5 | 463 | 27.8 |

| Women, n (%) | 966 | 64.8 | 81 | 72.3 | 346 | 47.1 | 527 | 80.0 | 288 | 62.6 | 467 | 66.4 | 296 | 65.5 |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 77.9 | ±6.9 | 82 | ±6.5 | 75.6 | ±7.0 | 80.1 | ±6.1 | 78.8 | ±6.9 | 78 | ±7.1 | 77.9 | ±7 |

| Years of education: mean±SD | 6.3 | ±4.4 | 6.8 | ±4.2 | 7.1 | ±4.4 | 5.6 | ±4.2 | 6 | ±3.9 | 6.2 | ±4.5 | 7.1 | ±4.6 |

| Institutionalised (n, %) | 13 | 1.8 | 25 | 3.8 | 52 | 11.2 | 49 | 7 | 14 | 3.1 | ||||

| Doctor who referred the patient (n, %) | ||||||||||||||

| General practitioner | 1293 | 84.9 | 77 | 65.8 | 624 | 84.0 | 585 | 86.4 | 413 | 86.9 | 601 | 83.6 | 370 | 80.4 |

| Neurologist | 90 | 5.9 | 5 | 4.3 | 54 | 7.3 | 35 | 5.2 | 11 | 2.3 | 32 | 4.5 | 51 | 11.1 |

| Psychiatrist | 43 | 2.8 | 9 | 7.7 | 26 | 3.5 | 14 | 2.1 | 20 | 4.2 | 25 | 3.5 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Geriatric specialist | 36 | 2.4 | 13 | 11.1 | 17 | 2.3 | 15 | 2.2 | 17 | 3.6 | 18 | 2.5 | 13 | 2.8 |

| Other | 60 | 3.9 | 13 | 11.1 | 22 | 3.0 | 27 | 4.0 | 14 | 2.9 | 43 | 6.0 | 18 | 3.9 |

| Specialist providing care (n, %) | ||||||||||||||

| Neurologist | 1141 | 75.1 | 56 | 47.9 | 568 | 76.7 | 480 | 71.1 | 280 | 58.7 | 527 | 73.8 | 390 | 84.8 |

| Geriatric specialist | 206 | 13.6 | 32 | 27.4 | 81 | 10.9 | 118 | 17.5 | 83 | 17.4 | 106 | 14.8 | 55 | 12.0 |

| Psychiatrist | 143 | 9.4 | 27 | 23.1 | 78 | 10.5 | 64 | 9.5 | 109 | 22.9 | 58 | 8.1 | 11 | 2.4 |

| Time to provide care | ||||||||||||||

| From first primary care visit, mean±SD | 1.3 | ±1.7 | 1.5 | ±2.2 | 1.3 | ±1.6 | 1.3 | ±1.9 | 1.3 | ±1.9 | 1.2 | ±1.8 | 1.4 | ±1.6 |

| Between symptom onset and first PC visit (months), mean±SD | 10.8 | ±17.0 | 11.5 | ±19.1 | 11.4 | ±16.3 | 10.5 | ±18.2 | 9.2 | ±17.5 | 11 | ±17.2 | 12 | ±16.8 |

| Between first visit and referral to a specialist (months), mean±SD | 7.9 | ±13.8 | 8.5 | ±16.1 | 7.1 | ±12.2 | 9 | ±15.1 | 9.5 | ±18 | 7.6 | ±12.5 | 7.5 | ±12 |

| Between symptom onset and monitoring (months), mean±SD | 19.5 | ±16.2 | 19.8 | ±13.6 | 18.8 | ±15.2 | 20.5 | ±17.0 | 19.8 | ±17.3 | 18.9 | ±15.8 | 20.2 | ±15.1 |

| MMSE, mean±SD | ||||||||||||||

| Total score | 17.8 | ±4.8 | 15.1 | ±4.8 | 18.5 | ±4.8 | 16.9 | ±4.7 | 16.8 | ±5 | 17.6 | ±4.8 | 18.6 | ±4.5 |

| Adjusted total | 19.3 | ±4.7 | 16.7 | ±4.8 | 19.7 | ±4.7 | 18.5 | ±4.7 | 18.3 | ±4.9 | 19 | ±4.7 | 20 | ±4.5 |

| NPI | ||||||||||||||

| Presence of any symptom, (n, %) | 1077 | 87.0 | 95 | 95.0 | 540 | 86.5 | 459 | 87.6 | 348 | 90.4 | 509 | 86.6 | 328 | 87 |

| Score, mean±SD | 11.7 | ±12.4 | 19.3 | ±19.0 | 10.8 | ±11.5 | 13 | ±13.6 | 14.2 | ±14.2 | 11.9 | ±12.5 | 11.1 | ±12.8 |

| CDR, (n, %) | ||||||||||||||

| Possible dementia | 278 | 18.8 | 3 | 2.6 | 166 | 23.1 | 88 | 13.4 | 80 | 17.3 | 118 | 17.1 | 85 | 18.8 |

| Mild dementia | 793 | 53.6 | 44 | 38.6 | 388 | 53.9 | 327 | 49.8 | 235 | 50.8 | 340 | 49.3 | 257 | 56.7 |

| Moderate dementia | 348 | 23.5 | 52 | 45.6 | 143 | 19.9 | 203 | 30.9 | 124 | 26.8 | 195 | 28.3 | 93 | 20.5 |

| Severe dementia | 52 | 3.5 | 15 | 13.2 | 18 | 2.5 | 35 | 5.3 | 22 | 4.8 | 33 | 4.8 | 13 | 2.9 |

Tests of statistical significance employed: for comparisons between 2 groups, the t-test was used for independent samples and quantitative variables; Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. For comparisons of more than 2 groups, we used analysis of variance for quantitative variables and Fisher's exact test, the chi-square test, or the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test as appropriate for each categorical variable. Statistically significant results (P<.05) are displayed in bold.

PC=primary care; CDR=clinical dementia rating; SD=standard deviation; MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination; NPI=neuropsychiatric inventory.

Comparison of subgroups broken down by care level.

| Specialist | Type of clinic | |||||||||||||||||

| Neurologist | Psychiatrist | Geriatric specialist | Other | Specialty centre | Hospital department | Tertiary care hospital unit | Dementia unit | Other | ||||||||||

| Total N, % | 1222 | 72.8 | 178 | 10.6 | 247 | 14.7 | 32 | 1.9 | 546 | 32.4 | 628 | 37.2 | 279 | 16.5 | 153 | 9.1 | 81 | 4.8 |

| Women, n (%) | 776 | 65.3 | 106 | 60.9 | 155 | 65.7 | 22 | 71.0 | 335 | 63.1 | 380 | 62.7 | 189 | 69.5 | 104 | 70.7 | 58 | 71.6 |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 77.9 | ±6.9 | 76.9 | ±7.5 | 80.4 | ±6.2 | 78.4 | ±9.3 | 77.7 | ±6.6 | 78.6 | ±7.2 | 77.9 | ±7.2 | 78.3 | ±7.4 | 79.7 | ±6.4 |

| Years of education: mean±SD | 6.5 | ±4.5 | 6 | ±4.1 | 6.2 | ±4.2 | 6.1 | ±4 | 6.4 | ±4.3 | 6.4 | ±4.5 | 6.2 | ±4.5 | 6.2 | ±4.3 | 7 | ±4.2 |

| Patients institutionalised (n, %) | 56 | 4.7 | 27 | 15.9 | 32 | 13.4 | 2 | 6.3 | 32 | 6.1 | 34 | 5.5 | 16 | 5.9 | 9 | 6.0 | 25 | 32.1 |

| Doctor who referred the patient (n, %) | ||||||||||||||||||

| General practitioner | 1042 | 85.6 | 143 | 80.3 | 196 | 79.4 | 20 | 62.5 | 489 | 89.7 | 556 | 89.4 | 194 | 69.8 | 107 | 69.9 | 60 | 74.1 |

| Neurologist | 79 | 6.5 | 8 | 4.5 | 8 | 3.2 | 1 | 3.1 | 15 | 2.8 | 7 | 1.1 | 48 | 17.3 | 23 | 15.0 | 3 | 3.7 |

| Psychiatrist | 34 | 2.8 | 16 | 9.0 | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 4.4 | 11 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.1 | 8 | 5.2 | 6 | 7.4 |

| Geriatric specialist | 10 | 0.8 | 10 | 5.6 | 21 | 8.5 | 8 | 25.0 | 6 | 1.1 | 13 | 2.1 | 15 | 5.4 | 10 | 6.5 | 5 | 6.2 |

| Other | 52 | 4.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 19 | 7.7 | 3 | 9.4 | 11 | 2.0 | 35 | 5.6 | 17 | 6.1 | 5 | 3.3 | 7 | 8.6 |

| Specialist providing care (n, %) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neurologist | 419 | 77.4 | 488 | 78.3 | 193 | 69.2 | 104 | 68.4 | 15 | 18.5 | ||||||||

| Geriatric specialist | 13 | 2.4 | 108 | 17.3 | 69 | 24.7 | 28 | 18.4 | 29 | 35.8 | ||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 109 | 20.1 | 23 | 3.7 | 5 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.3 | 36 | 44.4 | ||||||||

| Time to provide care | ||||||||||||||||||

| From first primary care visit (years), mean±SD | 1.2 | ±1.7 | 1.9 | ±2.3 | 1.3 | ±1.6 | 1 | ±1.2 | 1.4 | ±2 | 1.3 | ±1.6 | 1.2 | ±1.4 | 1.4 | ±1.7 | 1.4 | ±2.1 |

| Between symptom onset and first visit to GP (months), mean±SD | 11.6 | ±17 | 8.7 | ±17.1 | 8.8 | ±19 | 7.3 | ±9.7 | 9.2 | ±17.7 | 9.8 | ±16.9 | 13.4 | ±16.8 | 14.6 | ±15.8 | 13.1 | ±18 |

| Between first visit and referral to a specialist (months), mean±SD | 6.9 | ±12.5 | 15.4 | ± 20 | 9.4 | ±15.7 | 7.3 | ±12.9 | 9.4 | ±16.6 | 8.4 | ±13.8 | 6 | ±11 | 5.5 | ±9.7 | 9.5 | ±14.4 |

| Between symptom onset and monitoring (months), mean±SD | 19.1 | ±15 | 23 | ±19.3 | 19.6 | ±17.6 | 17.1 | ±20.7 | 18.9 | ±15.6 | 19 | ±15.3 | 20.3 | ±16.9 | 20.4 | ±16.1 | 24.2 | ±20.5 |

| MMSE, mean±SD | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total score | 18 | ±4.7 | 14.9 | ±5 | 17.7 | ±4.8 | 16.8 | ±4.6 | 17.4 | ±5 | 17.6 | ±4.8 | 18.3 | ±4.9 | 17.9 | ±4.7 | 16.5 | ±4.3 |

| Adjusted total | 19.4 | ±4.6 | 16.4 | ±5.1 | 19.3 | ±4.7 | 18.2 | ±4.4 | 18.9 | ±4.9 | 19 | ±4.7 | 19.7 | ±4.7 | 19.4 | ±4.5 | 18.1 | ±4.2 |

| NPI | ||||||||||||||||||

| Presence of any symptom, (n, %) | 849 | 86.2 | 135 | 92.5 | 182 | 91.5 | 22 | 75.9 | 374 | 85.0 | 448 | 89.4 | 193 | 86.5 | 114 | 85.1 | 65 | 97.0 |

| Score, mean±SD | 10.6 | ±11.8 | 20.4 | ±17.5 | 14.3 | ±12.1 | 14.7 | ±20.9 | 11.9 | ±13.1 | 12.1 | ±12.5 | 11.1 | ±11.8 | 11.9 | ±13.6 | 20.2 | ±18.2 |

| CDR, (n, %) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Possible dementia | 229 | 19.6 | 22 | 12/4 | 27 | 11.3 | 9 | 28.1 | 83 | 15.7 | 109 | 18.1 | 54 | 20.3 | 31 | 20.7 | 10 | 12.7 |

| Mild dementia | 620 | 53.1 | 72 | 40/4 | 134 | 56.1 | 14 | 43.8 | 277 | 52.6 | 315 | 52.2 | 139 | 52.3 | 79 | 52.7 | 34 | 43.0 |

| Moderate dementia | 276 | 23.6 | 63 | 35/4 | 68 | 28.5 | 6 | 18.8 | 146 | 27.7 | 148 | 24.5 | 60 | 22.6 | 35 | 23.3 | 26 | 32.9 |

| Severe dementia | 35 | 3.0 | 21 | 11.8 | 8 | 3.3 | 3 | 9.4 | 16 | 3.0 | 28 | 4.6 | 11 | 4.1 | 5 | 3.3 | 9 | 11.4 |

Tests of statistical significance employed: in comparisons between 2 groups, the t-test was used for independent samples and quantitative variables; Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. For comparisons of more than 2 groups, we used analysis of variance for quantitative variables and Fisher's exact test, the chi-square test, or the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test as appropriate depending on the categorical variables. Statistically significant results (P<.05) are displayed in bold.

PC=primary care; CDR=clinical dementia rating; SD=standard deviation; MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination; NPI=neuropsychiatric inventory.

These data reveal, for example, that if carers are sons or daughters rather than spouses, the patient is more likely to be an older woman with a lower educational level and a more severe condition. To cite further examples, mean ages are older in patients who are institutionalised or cared for by geriatric specialists, and patients in large cities are more likely than rural patients to be attended by a neurologist and diagnosed at an earlier stage of the disease (according to MME and NPI scores).

DiscussionResults from the EACE study suggest that most patients with AD in Spain are diagnosed by a specialist when the disease is in a moderate stage. This is shown by both the mean raw MMSE score of 17.6 and by the fact that more than 70% of the cases have an MMSE score of less than 20 points. Early diagnosis is possible, and it has even occurred in our population in a low percentage of cases of patients with an MMSE of 24 or less, but such cases are far from common. Most cases show disease progression, given that they are more frequently diagnosed in moderate than in mild stages. A sizeable percentage is also diagnosed in severe stages in which the chances of altering the course of the disease are much lower.

In our sample, the overall profile with regard to neuropsychiatric symptoms is similar to that described in the literature for the AD stage of disease. This situation also confirms that patients’ disease has progressed considerably by the time of diagnosis, since these symptoms are less common in initial stages of AD.22 If our patients generally begin receiving treatment in moderate stages of the disease, it seems clear that there is considerable room for improvement in this area. AD patients should have access to a treatment plan that would be able to provide some degree of improvement in order to affect the course of the disease at all levels. Since a diagnosis is typically not reached until more advanced stages, we are missing many treatment opportunities and failing to take advantage of options that would improve the clinical status of numerous patients. Reaching a diagnosis at a relatively early stage of the disease is the key to making good use of treatment options.3,4,8,23–25 It seems there is no longer any debate regarding early diagnosis and the distinction between AD and mild cognitive impairment.26,27 As a result, much of the effort in current research is directed at achieving reliable diagnosis of AD in phases of cognitive impairment that are not too advanced.11,13

The time elapsed between estimated onset of symptoms and obtaining a specialist's diagnosis is more than 2 years (mean of 28.4 months). Although this figure is similar to those cited in other studies,28 it is probably less than the true time elapsed because it was estimated retrospectively by informants in every case. This total time to diagnosis includes different stages; the duration of each stage may be due fundamentally to different factors which may be affected specifically. To cite an example, the average time of nearly 11 months between symptom onset and the first visit to a primary care doctor is clearly due in part to poor recognition and awareness of those symptoms by carers and the general population. Awareness-raising campaigns may have a positive effect on this time factor. On the other hand, the average of 8.1 months that it takes for a case to be referred from primary care to a specialist may be reduced by implementing the right mechanisms for identifying patients and referring them to specialist care. We should also point out the disparity among time-to-care measurements in the sample (Table 2), reflecting healthcare variability throughout Spain. The specialist care level shows room for improvement, although this study did not measure how much improvement is needed. Changes should be applied to the management of complementary diagnostic tests (analyses and neuroimaging) if these tests are not available from the first visit to the specialist.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, it is important to stress the high percentage of functionally illiterate patients. This finding resembles results from other series completed in the same geographical area.29 On the other hand, it comes as no surprise that geriatric specialists care for older patients, or that institutionalised patients would also be older than the non-institutionalised. The fact that institutionalised patients are less frequently seen by neurologists than by geriatric specialists and psychiatrists probably reflects the fact that neurologists do not typically work in institutional homes.

It is also logical that patients seen by psychiatrists would have more neuropsychiatric symptoms, a somewhat poorer clinical condition, and be more likely to require antipsychotic drugs (data not shown), even though their mean age is no older than the rest of the population's. The differences between groups of patients cared for by different specialists do not reflect different care approaches. Instead, they can be explained by logical referral biases according to each specialty and the location where the care is provided.

There is a statistically significant difference between patient stages according to the size of the city in which they are treated. In smaller cities, impairment will be more pronounced. This is true on both the cognitive level (a lower average MMSE) and a behavioural level (higher NPI score). This tendency may be due to a number of causes. It may in fact correspond to the variable ‘demand for attention’, such that there may be more demand for care in urban settings, which could be due to better awareness of the disease. At the same time, demand corresponding to mild cases may be lower in more rural settings in which the patient may receive more support from those in his or her environment. Organisational phenomena may also be involved; there may be a difference in specialist availability in these areas, or one may simply find different referral or clinical practices among professionals in different areas.

The EACE study has some obvious limitations. First of all, there is a selection bias inherent to the study design. Because of its design, the study will underestimate care provided by specialist units and clinics, since these units provided only 4 cases, just as the general clinics did. It may also underestimate care in large cities. While the study represents the entire geographical territory, representation is not exactly population-based. This bias may be less important than it seems, however. Results are fairly homogeneous when they are considered by different subgroups, and the overall level of dispersion for the sample is similar to the level of dispersion of its subgroups. Because of study characteristics, the data for each section are occasionally incomplete. Some disease progression data are retrospective estimates, but they are supported by data obtained objectively: time of referral, and first primary care visit due to AD symptoms. Using MMSE as a tool to classify dementia severity may overestimate that severity in patients with a low educational level. However, we find it much more reliable than CDR, an instrument that is much less widely used in Spain. We also believe that many researchers lack training and familiarity with the CDR. The study has many obvious strengths as well: its large sample size and ample representation of healthcare professionals. In addition, the fact that the study's results are similar to those from other series lends it credibility, despite the biases listed above.

Regardless of the study's limitations, we feel that the healthcare situation it describes demonstrates that AD is not normally diagnosed in patients in mild stages of the disease. If we are to diagnose patients in less-evolved stages, we should re-examine awareness campaigns according to what we know now. A greater effort should also be made to coordinate between care levels and create care circuits and referral protocols that will help us achieve this goal. Furthermore, this goal is desirable for society at large, not only from a humanitarian viewpoint, but also in terms of cost-effectiveness. Providing care, support, and treatment to a group of patients that is seriously affected by a treatable disease is more than a social and ethical requirement; it will actually lower the costs generated by that disease.

Conflicts of interestThe EACE study was financed by Pfizer España. Margarita González-Adalid is employed by Pfizer España. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank the 437 researchers who participated in EACE.

Please cite this article as: Alom Poveda J, Baquero M, González-Adalid Guerreiro M. Estadio evolutivo de los pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer que acuden a la consulta especializada en España. Estudio EACE. Neurología. 2013;28:477–487.

Results from this study were featured as an oral presentation at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the SEN, held in Barcelona in 2010.