Protein glycosylation is essential to the correct functioning of numerous biological processes, such as protein folding and stability, intracellular receptor binding, and intracellular communication, among others.1 Mutations affecting the encoding of certain proteins involved in glycosylation cause defects known as congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG), which are classified into different subtypes, depending on which point of the process is altered. Most CDGs affect multiple organs and systems. Patients with DPAGT1-CDG (MIM 608093) most frequently present psychomotor retardation, neuromuscular disease, hormonal abnormalities, and dysmorphic features.2

Congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMS) are caused by mutations in genes coding for proteins that are essential in maintaining neuromuscular transmission.3–5 These patients present muscle weakness exacerbated by fatigue; age of onset, distribution of muscle weakness, and treatment response are variable.3–5 Mutations in the ALG2, ALG14, GFPT1, GMPPB,5 and DPAGT1 (MIM 614750) genes may cause CMS with predominantly proximal weakness and little facial or eye involvement.6DPAGT1 mutations have traditionally been considered a CDG,7–9 progressing with slow growth, severe hypotonia, microcephaly, refractory epileptic seizures, and intellectual disability. Wurde et al.9 report the cases of 2 patients who died within their first year of life. Severe hypotonia in these patients reveals that neuromuscular function was altered. However, another patient group presents symptoms of congenital myasthenia without the other symptoms of DPAGT1-CDG.9

We present the case of a 10-year-old patient with 2 DPAGT1 mutations (compound heterozygote) who presents encephalopathy with symptoms of autism spectrum disorder and CMS (with proximal muscle involvement, no eye or bulbar symptoms), who has responded satisfactorily to treatment with pyridostigmine.

At the age of 10 months, the patient was referred to our department due to symptoms of dysmorphic syndrome, psychomotor retardation, and hypotonia. He had no family history of interest. Our patient's mother had experienced no complications during pregnancy or delivery, and the patient's neonatal period had been normal: weight at birth was 4150g and Apgar score was 9/10. The newborn blood spot test yielded normal results. The physical examination revealed some dysmorphic features: relative microcephaly, wide forehead, narrow palpebral fissures, widely spaced nipples, and abnormal distribution of fat, predominantly in the trunk and proximal muscles of limbs; limbs were thin in distal regions. He presented significant hypotonia and weakness. Deep tendon reflexes were weak. Psychomotor development was retarded, with the patient achieving head control at 7-8 months and unaided sitting at 2-3 years; however, he was unable to walk unaided. Symptoms have remained stable with no exacerbations over the patient's progression. At the age of 10, he presents severe intellectual disability, with little interest in his environment and a lack of expressive language. He does not present ataxia, dysmetria, ptosis, choking episodes, or dysphagia. The pattern of weakness predominantly affects the upper limbs; when agitated, the patient capably and accurately defends himself using his lower limbs.

Results from complementary testing, including biochemical analysis, brain MRI scan, and a neurometabolic study, were normal. At 3 years, an EMG study revealed a myopathic pattern. Muscle biopsy revealed signs of myopathy with muscle fibre disproportion. Electron microscopy was not performed, which probably delayed diagnosis. Considering the patient's cognitive impairment, we studied serum asialotransferrin (2009), which revealed a type 1 pattern compatible with type 1 glycosylation. Diagnosis of DPAGT1-CDG was confirmed by massive sequencing, which identified 2 mutations: c.329T>C (p.Phe110Ser, which had not previously been described), and c.902G>A (p.Arg301His) in the DPAGT1 gene. He has since been under follow-up by the cardiology, ophthalmology, and endocrinology departments, with no further relevant complications. Tests for anti-acetylcholine receptor and anti-muscle-specific kinase antibodies yielded negative results.

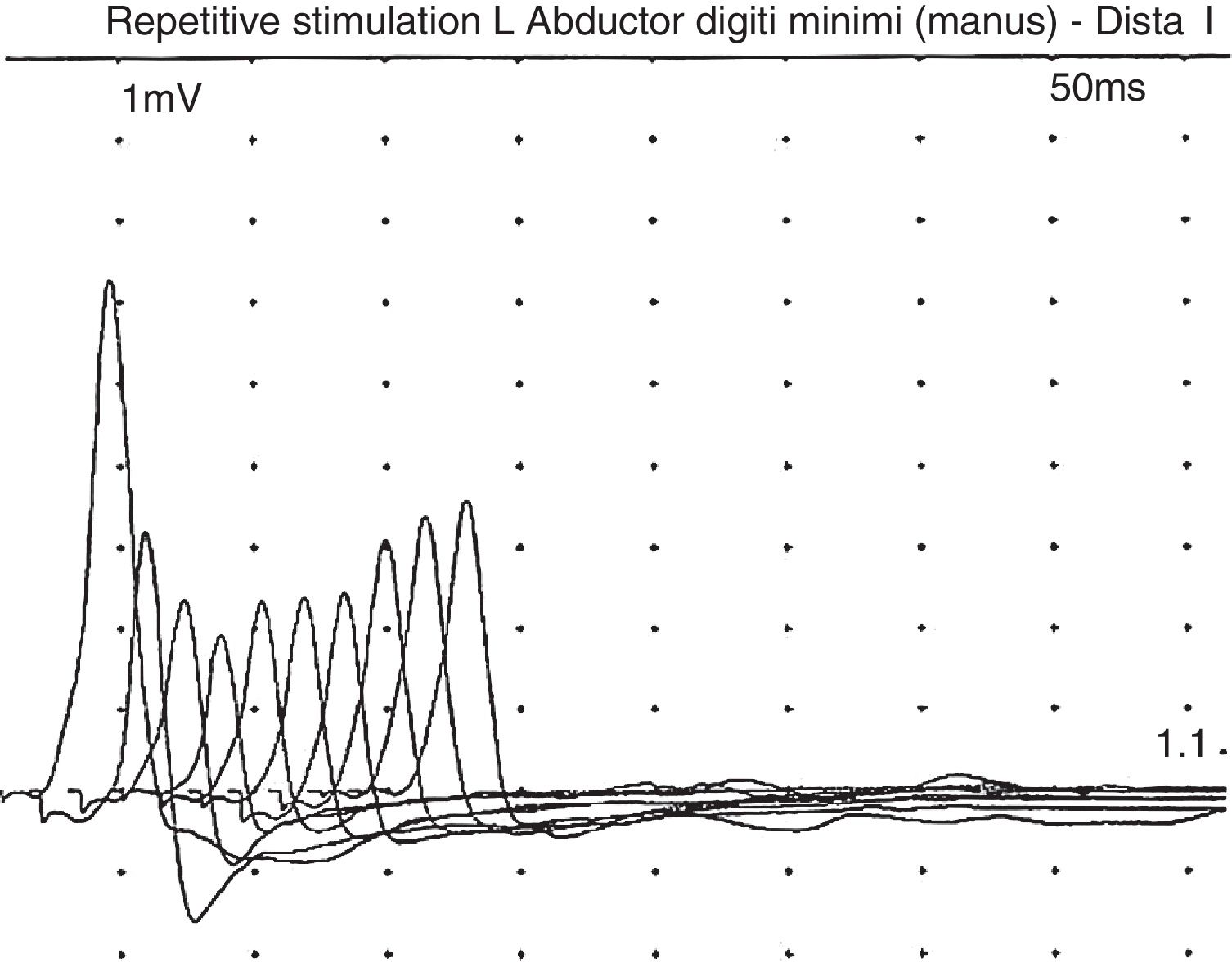

In a recent visit when the patient was 10 years old, his family commented that his muscle weakness had increased (without ptosis or bulbar symptoms) after intensive physical therapy, but he recovered after a rest period. After reviewing the literature, and given the possibility of myasthenic symptoms, the patient underwent another EMG, this time with the focus on that disease; this revealed a clearly decreased response (40%) to repetitive stimulation (Fig. 1). In view of this finding, we decided to administer pyridostigmine, which improved the patient's fatigability and strength, enabling him to walk several metres with assistance, to rise from a chair, and to improve his posture when seated. This was confirmed by the Myasthenia Gravis Composite,10 with the patient scoring 9 before pyridostigmine treatment, presenting moderate weakness in the neck and proximal weakness in the shoulders and hips; after treatment with pyridostigmine at 120mg/8h, he obtained a score of 4 on the Myasthenia Gravis Composite, with mild weakness in the hips and shoulders.

The most striking finding in our patient, unlike in other published cases, is the copresence of mild-to-moderate muscle weakness (which improved progressively) and significant cognitive impairment, despite which the patient has progressed favourably, with no respiratory complications, epilepsy, or feeding difficulties. Considering the positive initial response to pyridostigmine, we expect his quality of life to continue improving.

DPAGT1 dysfunction causes a defect in several components of the neuromuscular junction: acetylcholine receptor subunits, agrin, muscle-specific kinase, and laminin.11 Patients with DPAGT1 mutations also display a reduced amount of acetylcholine receptor in the motor end plate.2 These changes explain the positive response to pyridostigmine usually observed in these patients. The combination of these alterations is sufficient to explain their muscle weakness.

Symptoms are usually severe: of the 28 reported patients, 23 died before the age of 5.12 Most patients presented moderate-to-severe intellectual disability (although some patients have normal intelligence),13 microcephaly, hypotonia, and epilepsy. Other less frequent symptoms were feeding difficulties, apnoeas, respiratory failure, chronic anaemia, cataracts, hypertrichosis, hypertonia of the limbs, arthrogryposis, tremor, inverted nipples, abnormal distribution of fat, papillary atrophy, or neurosensory hypoacusia.12–14 Serum asialotransferrin profile was altered in all cases. Of the 28 reported cases, 13 presented CMS. In some patients, symptom onset may occur later, even as late as the age of 17.12–14 Myasthenia in these patients progresses with predominantly proximal weakness exacerbated by exercise (fatigability), which does not normally affect the eye or facial muscles.12–14 Most patients presented a very satisfactory response to pyridostigmine.12–14 The characteristic EMG pattern consisted of decreased response to repetitive stimulation at 3Hz.11,12 Neuroimaging results were usually normal.

It is yet to be determined why mutations in the same gene can provoke different types of manifestations. The neuromuscular junction seems to be especially sensitive to deficiency of DPAGT1, and the slightest reduction in its activity may therefore be sufficient to cause symptoms.

With regard to our patient, cases with such early onset usually present a poorer progression (dying within the first years of life). In the case of a child with cognitive impairment, microcephaly, and muscle weakness with little or no eye or facial impairment, we should consider that symptoms may be explained by a mutation in DPAGT1, since this may have an effect on prognosis and treatment.

Please cite this article as: Ibáñez-Micó S, Domingo Jiménez R, Pérez-Cerdá C, Ghandour-Fabre D. Miastenia congénita y defecto congénito de la glucosilación por mutaciones en el gen DPAGT1. Neurología. 2019;34:139–141.