Aortic dissection is an infrequent condition associated with a high mortality rate.1–3 The main risk factor is chronic arterial hypertension, followed by obesity, tobacco use, and connective tissue diseases.1–3 Aortic dissection typically manifests with sudden, intense chest, abdominal, or interscapular pain.1–3 The Stanford classification distinguishes 2 types: type A, more frequent and severe, involves the ascending aorta and requires emergency surgery, whereas type B affects the descending aorta.1,2 Although aortic dissection is a rare cause of ischaemic stroke, it does often present with neurological symptoms.2–4 We present the case of a patient with a type A aortic dissection manifesting as ischaemic stroke, and provide a brief literature review.

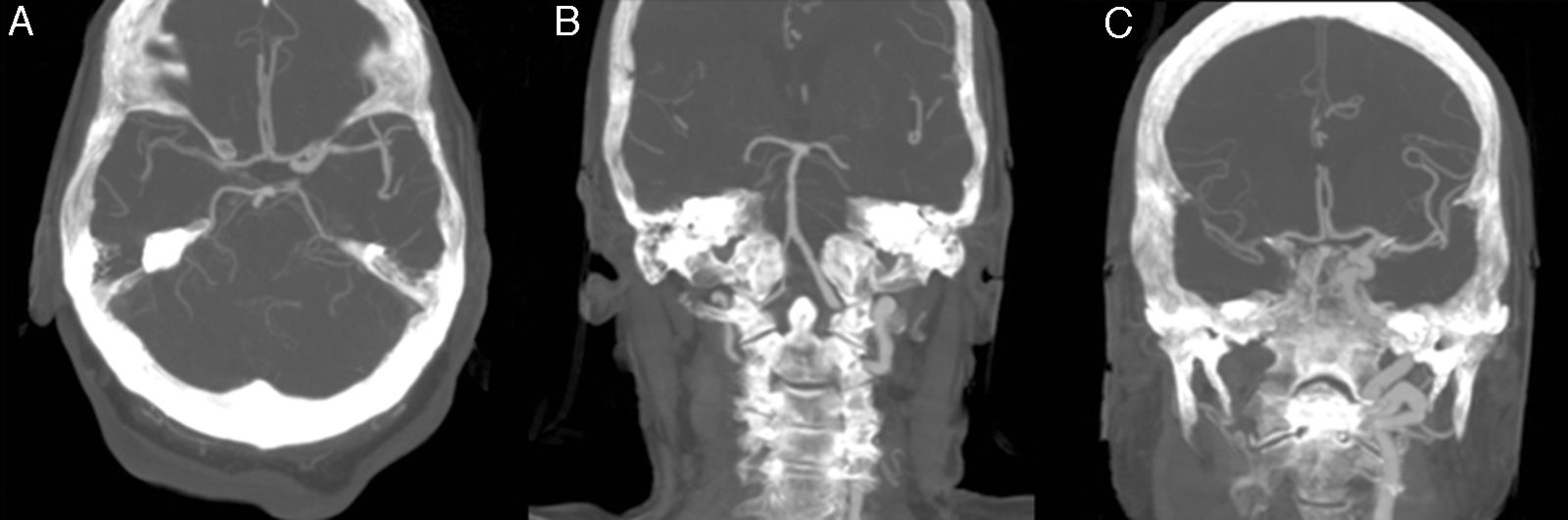

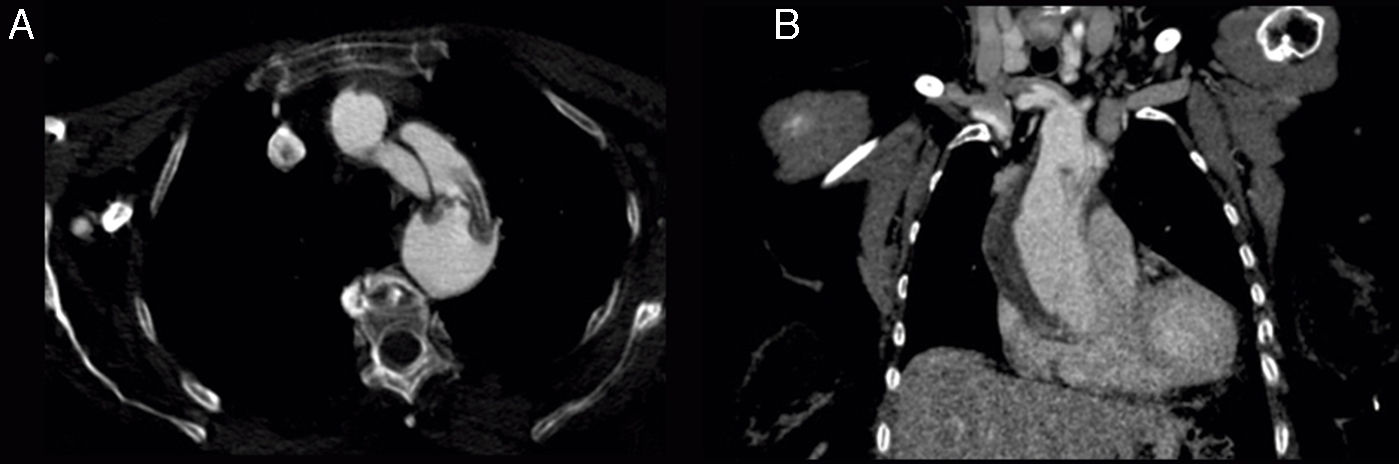

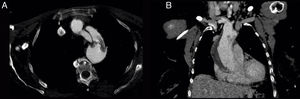

The patient was an 81-year-old woman with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidaemia. She had had a lacunar stroke (incomplete left-sided sensorimotor stroke) 3 weeks previously; a thorough neurosonology study and a transthoracic echocardiogram performed during admission revealed no alterations. The patient started antiplatelet therapy. A week before visiting the emergency department, she underwent hip fracture surgery, receiving low molecular weight heparin. The patient was at her home when she suddenly presented diplopia, followed by dysarthria and a low level of consciousness. She arrived at the emergency department 30minutes later; she was haemodynamically stable and had no fever. Although the electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm, her limbs were cold and her pulse weak. The patient showed no heart murmur or asymmetric pulses. During the initial neurological examination, the patient did not open her eyes either spontaneously or in response to any type of stimulus and did not understand or produce language. She showed anarthria, bilateral absent menace response, normal pupils, roving eye movements, predominantly left-sided flaccid paresis, no plantar response bilaterally, and motor response to painful stimuli in the right limbs only. These findings were suggestive of vertebrobasilar stroke. Following our centre's protocol for managing code stroke patients with suspected large-vessel involvement, we performed baseline CT, CT perfusion, and CT-angiography of the supra-aortic trunks and circle of Willis. An additional neurological examination performed before the imaging study demonstrated the following changes: the patient was conscious and alert, she spoke little but showed no signs of aphasia, she had mild dysarthria, left hemispatial neglect, absent menace response of the left eye, and left-sided hypoaesthesia and faciobrachicrural hemiparesis. Unlike the previous results, these findings were suggestive of ischaemia in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery. The baseline CT scan revealed no signs of hyperacute ischaemia. CT perfusion displayed alterations in the vertebrobasilar territory bilaterally and the territory of the right middle cerebral artery. CT-angiography showed no contrast uptake in the right carotid axis, and partial repletion of the middle cerebral artery with blood flow from the contralateral artery. Only the dural segment of the right vertebral artery was visible (Fig. 1A and C). The left carotid axis, both anterior cerebral arteries, the left middle cerebral artery, and the left vertebral artery appeared to be normal. The basilar artery and both posterior cerebral arteries had filiform stenoses but there was no evidence of dissection (Fig. 1B). No posterior communicating arteries were observed. We identified an intimal flap in the aortic arch (Fig. 2), suggesting aortic arch dissection. A chest and abdomen CT scan confirmed type A aortic dissection with a mural thrombus in the ascending aorta. The dissection reached the brachiocephalic artery, right subclavian artery, and right common carotid artery. The patient died several minutes after the study concluded, 2hours after symptom onset.

CT-angiography of the circle of Willis. (A) Axial plane showing partial repletion of the right middle cerebral artery. (B) In a coronal reconstruction of the posterior circulation, only the distal segment of the right vertebral artery is visible; the basilar and posterior cerebral arteries demonstrate filiform stenoses. (C) A coronal reconstruction of the anterior circulation shows lack of repletion of the right internal carotid artery and partial repletion of the right middle cerebral artery.

Neurological symptoms appear in 17% to 40% of patients with aortic dissection,4,5 especially those with type A aortic dissection.4,6 The most frequent neurological manifestations include ischaemic stroke (6%-32%),3,5,6 especially right hemispheric stroke (69.2%-71%),3–6 and in some cases bilateral stroke.7 The predominance of right hemispheric strokes has been linked to the greater proximity between the right carotid axis and the aortic root, which increases the vulnerability of the carotid artery origins to the advancing dissection.4 There are 2 possible pathogenic mechanisms: (1) the dissection may block blood flow through the supra-aortic trunks or advance towards them, or less frequently, (2) a mural thrombus may cause artery-to-artery embolism if it reaches the true lumen.4,5 Although pain is the main symptom of aortic dissection, one third of patients with associated ischaemic stroke do not experience pain,3,4 compared to only 5% to 15% of all patients with aortic dissection.3 The low level of consciousness and speech and language alterations may hinder or prevent detection of this symptom.3,5 This explains the difficulty of detecting aortic dissections initially manifesting with neurological symptoms and the consequent higher mortality rates (30%) than those seen in other cases of aortic dissection (22.6%).3 Several complementary tests are used to diagnose aortic dissection; however, given that aortic dissection rarely causes ischaemic stroke, patients with ischaemic stroke are rarely screened for the condition.4 Aortic dissection must be ruled out when the condition is suspected (pain characteristic of the condition or typical signs such as low blood pressure; a weak, asymmetric pulse; and murmur of aortic regurgitation2,5): although stroke is not a contraindication for surgery for type A aortic dissection,4,7 aortic dissection does contraindicate intravenous fibrinolysis,4,5,8 with a mortality rate of 71% in patients receiving rTPA.7 Chest radiography shows mediastinal widening or aortic enlargement in 50% of cases.2 While the sensitivity of transthoracic echocardiography is highly variable (35%-80%), transoesophageal echocardiography has a sensitivity of 98%.2 Elevated D-dimer concentrations have a high sensitivity yet low specificity for diagnosing aortic dissection; negative results may therefore rule out the condition.1,5 Aortic dissection is usually diagnosed with MRI-angiography or, even more frequently, with CT-angiography, as this technique is readily available. MRI-angiography has 95% to 100% sensitivity and specificity, whereas CT-angiography has 83% to 94% sensitivity and 87% to 100% specificity.2 Transthoracic echocardiography of the aorta (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma [FAST])7 is a fast, non-invasive technique for ruling out the condition when the patient is eligible for intravenous fibrinolysis.

Our patient had no pain and did not exhibit any of the classic signs of aortic dissection. These cases require a high level of suspicion, since systemic manifestations may be scarce or not predominant.2

We should also point out the fluctuating nature of the patient's symptoms, with 2 different territories being affected almost immediately. This finding should signal possible aortic dissection since few processes are able to trigger such symptoms.

Although neurological symptoms usually appear at the onset of aortic dissection,4 in our case, onset may have occurred 3 weeks previously (chronic dissection2), causing the first stroke; antiplatelet therapy following stroke plus low molecular weight heparin administered after surgery may have led to the fatal outcome. The dissection may have gone undetected by transthoracic echocardiography since the study did not focus on the aortic root. The aortic root and arch should therefore be studied in cases of stroke of unknown cause; this will help to rule out not only aortic dissection but also ateromatosis.

Please cite this article as: Muñiz Castrillo S, Oyanguren Rodeño B, de Antonio Sanz E, González Salaices M. Ictus isquémico secundario a disección aórtica: un reto diagnóstico. Neurología. 2018;33:192–194.