Most cases of secondary intracranial hypertension are due to intracranial processes.1 Spinal tumours are a well-known yet infrequent cause of intracranial hypertension, and are usually associated with hydrocephalus.2 These tumours rarely manifest with intracranial hypertension and without hydrocephalus. We present the case of a young man who developed intracranial hypertension without hydrocephalus and was subsequently diagnosed with a spinal tumour. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain a high level of suspicion in atypical cases of intracranial hypertension combined with normal neuroimaging results, in order to detect other, less frequent causes of intracranial hypertension.

The patient was a 19-year-old man with no relevant medical history. A year prior to admission, he began to experience lower back pain radiating to the lower limbs, and was initially diagnosed with bilateral sacroiliitis. Pain worsened progressively despite anti-inflammatory treatment. A month prior to admission, the patient began to experience oppressive holocranial headache, which worsened with Valsalva manoeuvres and was associated with blurred vision and horizontal diplopia. He also reported tinnitus and transient bilateral vision loss.

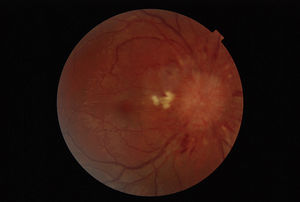

The neurological examination revealed bilateral papilloedema (Fig. 1), decreased visual acuity bilaterally, and paresis of both lateral rectus muscles. The pain had caused decreased muscle strength in the lower limbs and was more intense during the straight leg raise test. Stretch reflexes were absent in the lower limbs and normal in the upper limbs; sensitivity was preserved.

The results of a cranial CT scan were normal. An MRI scan of the dorsal and lumbar region showed a space-occupying mass in the conus medullaris, which was hypointense in T1 and highly heterogeneous in T2. The mass displayed contrast uptake and was partially intramedullary and partially intradural extramedullary (Fig. 2). These findings are compatible with ependymoma.

The tumour was resected; a biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. The patient remains asymptomatic after one year of follow-up.

Differential diagnosis of intracranial hypertension usually focuses on ruling out intracranial processes. The diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension include absence of ventriculomegaly, masses, or intracranial structural or vascular lesions, but do not specifically mention extracranial processes. Though infrequent, intracranial hypertension secondary to spinal disorders is well documented in the literature. It is widely accepted that secondary intracranial hypertension can be caused by alterations in cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, which leads to secondary hydrocephalus.2 Furthermore, spinal tumours may reduce the elasticity of the central canal of the spinal cord, increasing intracranial pressure.3 Although several hypotheses have been proposed, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying intracranial hypertension in patients with spinal tumours are yet to be determined.4 Intracranial hypertension without hydrocephalus, as in our case, is even less frequent. In these cases, the extracranial process may go undetected. Therefore, a high level of suspicion and a thorough evaluation are necessary to detect other less frequent causes of intracranial hypertension in these patients.

It is difficult to determine which patients should undergo a complete diagnostic study to rule out less frequent secondary causes of intracranial hypertension. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension mainly affects young women with obesity.5 In patients not meeting this profile, the condition may have different features and be associated with a higher incidence of the less frequent causes of intracranial hypertension.6 Based on the above, a possible approach would be to differentiate patients by phenotype. In patients with the classic profile (young women of childbearing age), additional emphasis should be placed on detecting less frequent causes of secondary intracranial hypertension. The condition is diagnosed when the patient shows no focal neurological signs other than those associated with intracranial hypertension. As a result, atypical neurological findings suggest presence of other less frequent causes of intracranial hypertension.

In the case of spinal tumours, we should pay attention to presence of lower back pain, lower limb weakness, sphincter dysfunction, or abnormal myotatic reflexes. Our patient, who experienced intracranial hypertension associated with normal neuroimaging findings, was a young man with a normal body mass index. He did not meet the classic patient profile. Furthermore, he had a one-year history of lower back pain and displayed abolished myotatic reflexes in the lower limbs. In the light of the above, we decided to study the spinal region, detecting an ependymoma.

Intracranial hypertension has been associated with a wide range of tumours,2,7 including ependymomas,8 primitive neuroectodermal tumours,9,10 astrocytomas,11,12 neurinomas,13,14 and paragangliomas.15

In this case, the anatomical pathology study confirmed that the mass was an ependymoma. Tumour resection led to complete symptom resolution. It has been suggested that tumour resection restores central canal elasticity, leading to rapid resolution of intracranial hypertension.3

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Miranda Bacallado Y, González Hernández A, Curutchet Mesner L, Rúa-Figueroa Fernández de Larrinoa I. Papiledema bilateral como forma de debut de un ependimoma espinal. Neurología. 2018;33:194–196.

This study was presented in poster format at the 64th Annual Meeting of the SEN.