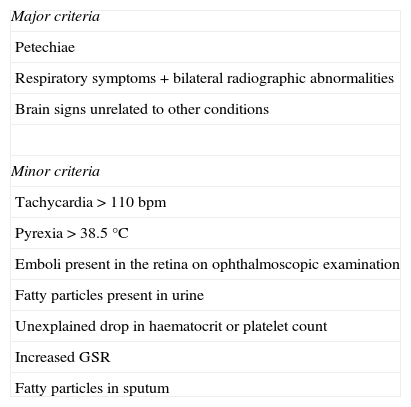

Fatty Embolism Syndrome (FES) is an uncommon yet potentially fatal complication of long bone fractures. Its hallmark is the classic triad consisting of hypoxaemia, neurological alteration, and petechial skin rash. Minor diagnostic criteria include tachycardia, fever, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, abnormal ophthalmoscopic findings, and fatty particles in sputum, or urine. According to Gurd's criteria (Table 1), the diagnosis is made when at least one major and four minor criteria are present.1

Gurd's criteria.

| Major criteria |

| Petechiae |

| Respiratory symptoms+bilateral radiographic abnormalities |

| Brain signs unrelated to other conditions |

| Minor criteria |

| Tachycardia>110bpm |

| Pyrexia>38.5°C |

| Emboli present in the retina on ophthalmoscopic examination |

| Fatty particles present in urine |

| Unexplained drop in haematocrit or platelet count |

| Increased GSR |

| Fatty particles in sputum |

GSR, glomerular sedimentation rate.

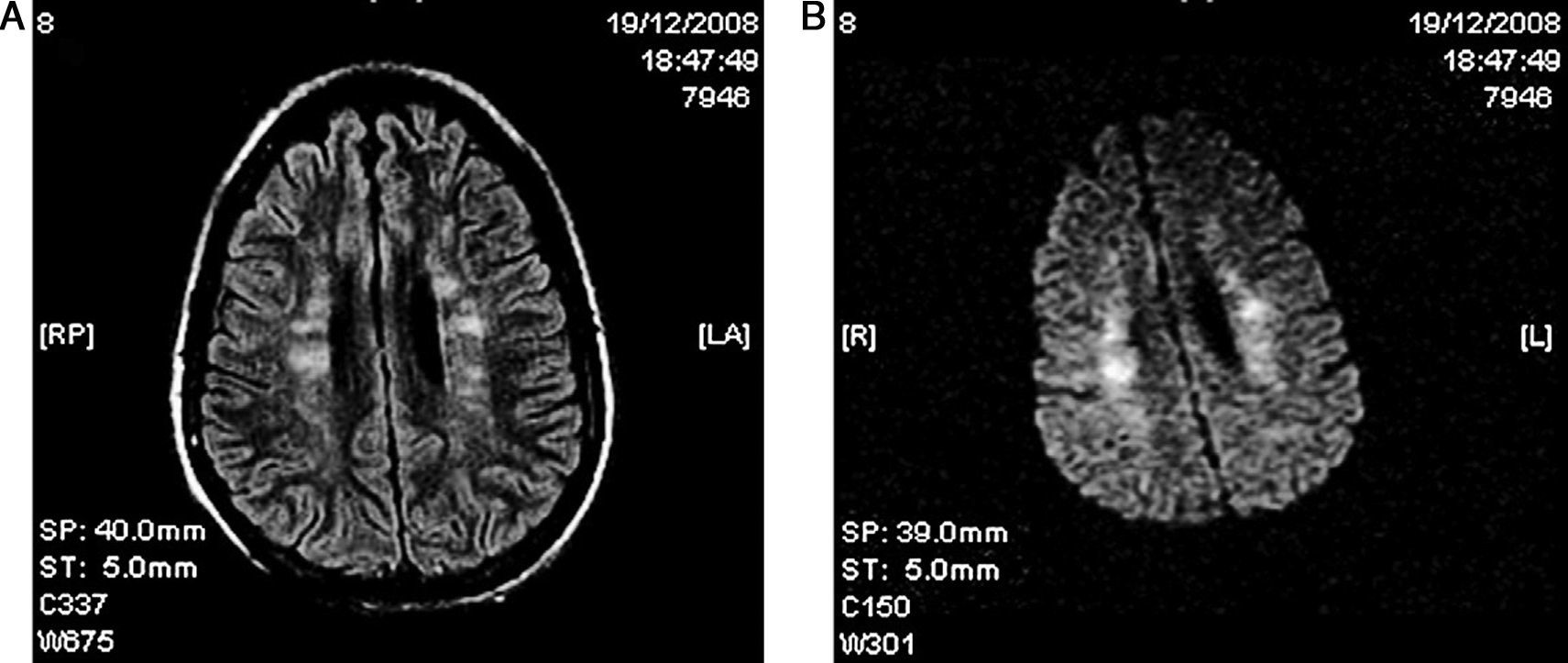

The diagnosis is largely clinical, but cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can reveal characteristic acute lesions in the central nervous system (CNS).

We report a new case of FES with distinctive findings on the MRI and on ophthalmoscopic images.

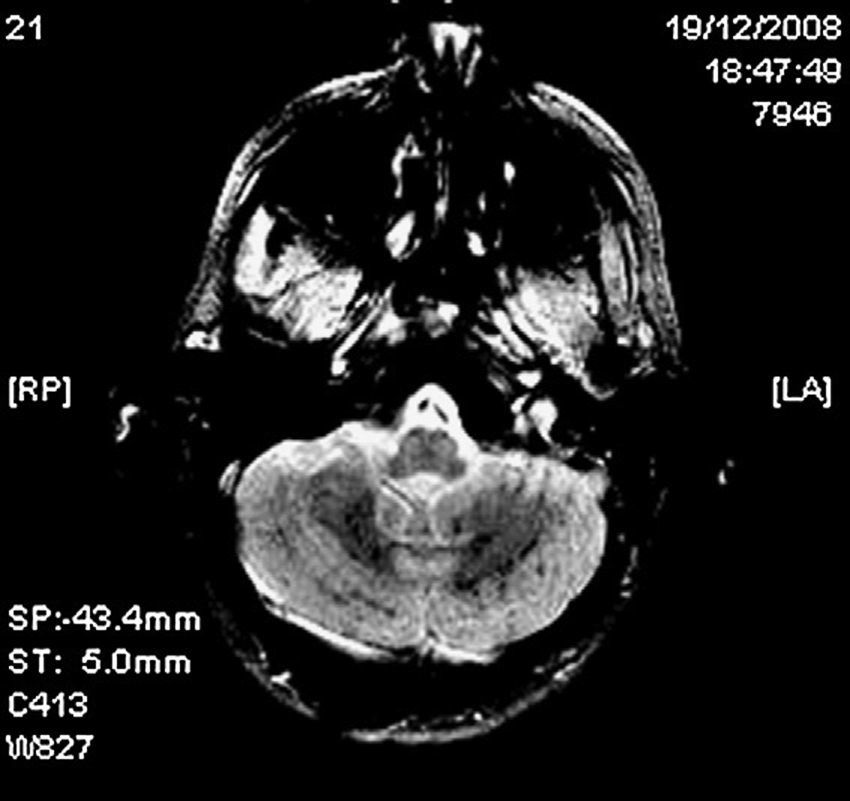

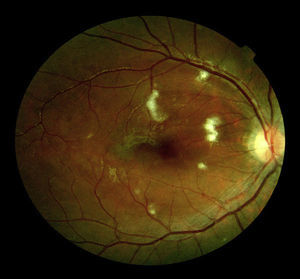

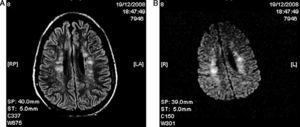

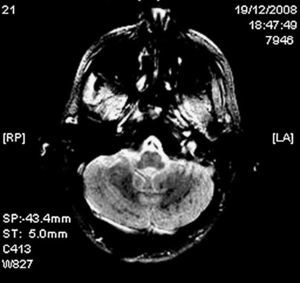

A 25 year old previously healthy male patient presented a bilateral femoral fracture following a cycling accident, without evidence of head trauma. He was admitted to our centre with a score of 15 on the Glasgow scale (GCS) and without any alterations in the neurological examination; bone traction was immediately put into place. Twenty-four hours later, he developed respiratory failure and decreased level of consciousness requiring emergency oro-tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. In view of the severity and vital urgency of the clinical picture, a neurological examination was not performed prior to intubation. A cranial computerized tomography (CT) was normal and a chest CT revealed bilateral alveolar consolidation. The examination of the fundus oculi revealed cotton wool exudate and bilateral macular oedema (Fig. 1). Surgical reduction with internal fixation of the fractures was performed 20 days after admission. On the cerebral MRI, in the T2 and FLAIR sequences, hyperintense foci are seen in the bilateral subcortical and periventricular white matter, with areas of restricted diffusion in the diffusion-weighted images (DWI) (Fig. 2). The gradient echo sequence (GRE) should diffuse spotty hypointensities compatible with localized micro-haemorrhages in the corpus callosum, the subcortical and deep white matter, the internal white capsule, and the cerebellar hemispheres (Fig. 3). The trans-oesophageal echocardiogram rules out the existence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO). It was decided not to perform a right-to-left shunt transcranial Doppler study using micro air bubbles because the patient's status did not allow the test to be properly performed with the Valsalva manoeuvre, and also to avoid the passage of new fatty emboli during the manoeuvre. Continuous HITS (high intensity transient sound) monitoring was also not performed to detect cerebral microemboli. No skin lesions were found.

The patient remained in the intensive care unit for 24 days during which time sedation-analgesia was gradually removed and extubation was performed without incident. The patient was transferred to the neurology ward with slight tetraparesis and difficulty in uttering language, while conserving the ability to understand simple orders. During his stay on the ward, his neurological status gradually improved and at the time of release (2 months after admission) he was: conscious, oriented, with a degree of slowed thinking, and normal language; from a motor perspective, he began physical therapy and recovered mobility in his upper limbs and with slight weakness and hypertrophy in the lower limbs, largely related to the physical trauma he suffered.

Fatty embolism occurs to a greater or lesser extent in almost 100% of all long bone fractures in the legs, but FES is present in only 0.5–3.5% of these cases, with a mortality rate of approximately 10%.2 It mainly affects young males and patients with multiple closed fractures.3 Early surgical correction has been seen to reduce the risk of developing FES significantly in comparison with conservative, traction-based treatment.4

Its pathogenesis is not clear and two possibilities have been proposed. First of all, the mechanical theory establishes that the increased pressure in the bone marrow due to a fracture or surgical manipulation fosters the passage of fatty emboli from the bone marrow to the pulmonary circulation, where the largest fatty emboli obstruct the pulmonary capillaries, while the smallest emboli can pass through and reach the systemic circulation. These fatty particles can also reach the systemic circulation by means of an intrapulmonary shunt or a PFO, thereby causing embolization in the brain, kidney, retina, or the skin.2,5 Secondly, the biochemical theory posits that the fat releases free fatty acids through the action of serum lipases, which alter the permeability of the capillary endothelium, giving rise to oedema and petechial haemorrhage, as in the case presented here.

FES generally manifests between 24 and 72h following trauma. Pulmonary symptoms tend to be the first to appear6 and occur in approximately 95% of patients. Symptoms of neurological dysfunction can be seen in up to 60% of the cases and headache, impaired level of consciousness, focal deficits, seizures, or coma may be present. The intensity of the neurological involvement is quite variable and is frequently reversible. Skin rash is seen in 33% of cases and is mainly observed on the chest, neck, axillae, and on the oral and conjunctival mucosae. These skin lesions usually resolve within one week.

Examination of the fundus oculi will usually reveal multiple cotton-wool exudates, oedema, and retinal bleeding around the optic nerve, all of which is secondary to multiple infarcts of the nerve fibres.6,7

The diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical findings and the most widely used diagnostic criteria are those put forth by Gurd.1 Cerebral MRI is useful to demonstrate typical findings, such as diffuse hyperintense foci in the long TR sequences located in subcortical or periventricular white matter and centrum semiovale. Some of these lesions present restriction on the DWI sequence, corresponding to the ischaemia-related cytotoxic oedema. The GRE sequence may show low signal, spotty foci compatible with micro-haemorrhages in several regions. Furthermore, MRI can help to rule out other trauma processes, such as diffuse axonal lesion, contusion or haematoma.8 It also aids in establishing the prognosis of brain damage, since some studies have shown that the number of lesions on the MRI correlates with the GCS score and that disappearance of the brain lesions is related to the resolution of the neurological symptoms.9

In conclusion, the presence of neurological decline in a patient with multiple fractures, especially 24–72h following trauma, should lead us to suspect FES. Findings on the cerebral MRI and the ophthalmoscopy are useful in making the diagnosis and ruling out other aetiologies. Despite the extensive lesions present on neuroimaging studies, prognosis may be favourable, as was the case of our patient.