Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism (MOPD) is a syndrome characterised by intrauterine growth retardation, impaired postnatal growth, microcephaly, and a phenotype similar to that of Seckel syndrome.1 MOPD type II, the most distinctive type of MOPD, is a rare disorder with a recessive autosomal inheritance pattern. We recently published the case of a Colombian carrier of a new mutation of the PCNT gene with a nucleotide change in exon 10, c.1468C>T, resulting in a premature stop codon at amino acid position 490, p.Q490X, which is predicted to generate a truncated protein.2

When the case was reported, the patient was 5; he was extremely small (below the third percentile for his age), with delayed psychomotor development and microcephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissure, a prominent nose, amelogenesis imperfecta, ulnar deviation, a high narrow pelvis, unusually short arms and legs, coxa vara, a high-pitched voice, and an outgoing personality.2 Complementary tests performed when he was 4 included a simple brain CT scan and an angiography. The CT scan showed no alterations in the fourth ventricle and posterior fossa, closure of the metopic and sagittal sutures, and permeability of the coronal and lambdoid sutures, whereas the angiography revealed no aneurysms or signs of moyamoya disease. We requested a molecular study to confirm the diagnosis.

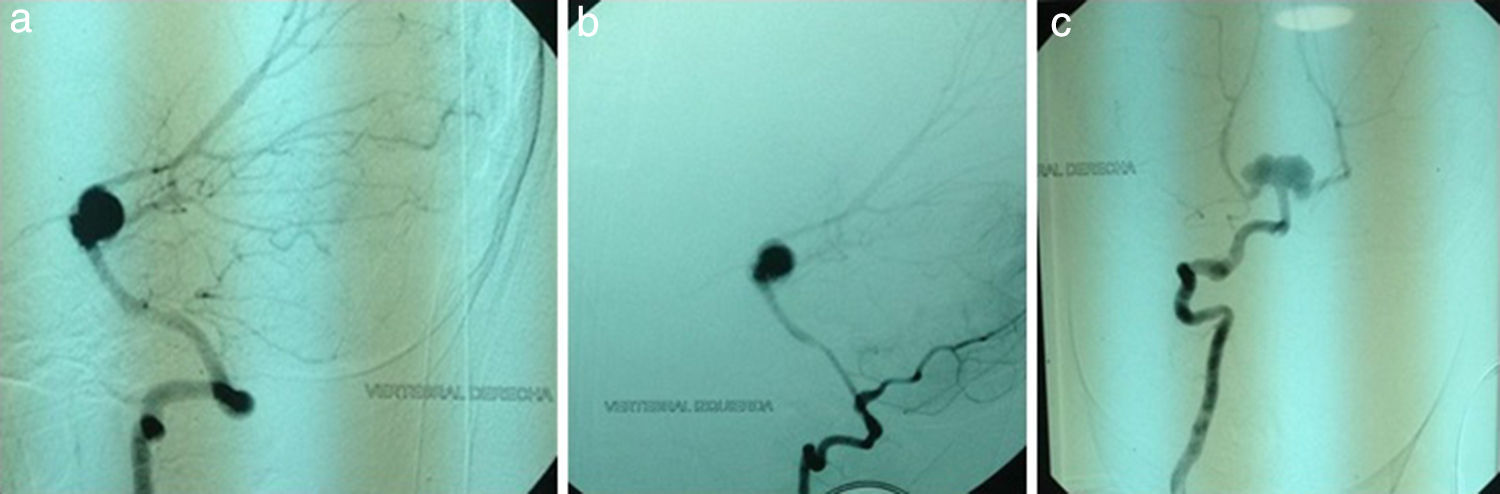

At the age of 7 (present), our patient experienced an episode of sudden headache associated with nausea, vomiting, seizures, loss of consciousness, and motor deficits. A brain CT scan displayed subarachnoid haemorrhage. An angiography study revealed infundibular dilation of the posterior communicating artery at the level of the left internal carotid artery, a transitional aneurysm in the left carotid artery measuring 3mm, an infundibular dilation of the posterior communicating artery at the level of the right internal carotid artery, and an aneurysm measuring 13mm at the apex of the basilar artery with clear signs of trilobular rupture compromising the origin of both posterior cerebral arteries (Fig. 1A–C). Although endovascular treatment achieved mild improvements in the patient's level of consciousness, quadriparesis and severe speech impairment persisted.

Vascular malformations in moyamoya disease and multiple aneurysms have been associated with various genetic disorders, especially MOPD type II. Hall et al.3 found aneurysms or moyamoya disease in 11 patients of a cohort of 58 (19%). Brancati et al.4 documented presence of these abnormalities in 15 of 63 patients (23.8%) and Bober et al.5 in 13 of 25 patients (52%). In these studies, cerebrovascular anomalies were more frequent in males.3–5 However, questions remain as to whether female sex has a protective effect or if instead male sex increases the risk of presenting these alterations.5

Neurological impairment secondary to cerebrovascular alterations results in a wide range of sequelae, from residual dysphasia to sudden death.3–5 In the study by Brancati et al.,4 patients with moyamoya disease were found to have cerebrovascular alterations at younger ages; patients with intracranial aneurysms in the posterior cerebral arteries, on the other hand, had a poorer prognosis due to severe chronic hypertension and dilated myocardiopathy.4

Diagnosis of multiple aneurysms and/or moyamoya disease is especially difficult in patients with MOPD type II due to the associated anatomical alterations, such as an unusually small vascular system and abnormally tortuous arteries.6 Given the close relationship between MOPD type II and cerebrovascular alterations, our case underscores the importance of conducting MRI or angiography screening tests annually in these patients to prevent potentially disabling or fatal events,5 enable early treatment, reduce surgery-related complications, and increase patients’ survival and quality of life. Patients with symptoms suggestive of MOPD or a diagnosis of MOPD confirmed by genetic studies should undergo routine angio-MRI studies to rule out aneurysms or moyamoya disease.

FundingThis study has received funding from the Congenital Anomalies and Rare Diseases Research Centre (CIACER) at Universidad Icesi, Colombia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Botero F, Pachajoa H. Múltiples malformaciones vasculares en un paciente con enanismo primordial osteodisplásico microcefálico tipo ii. Neurología. 2017;32:127–129.