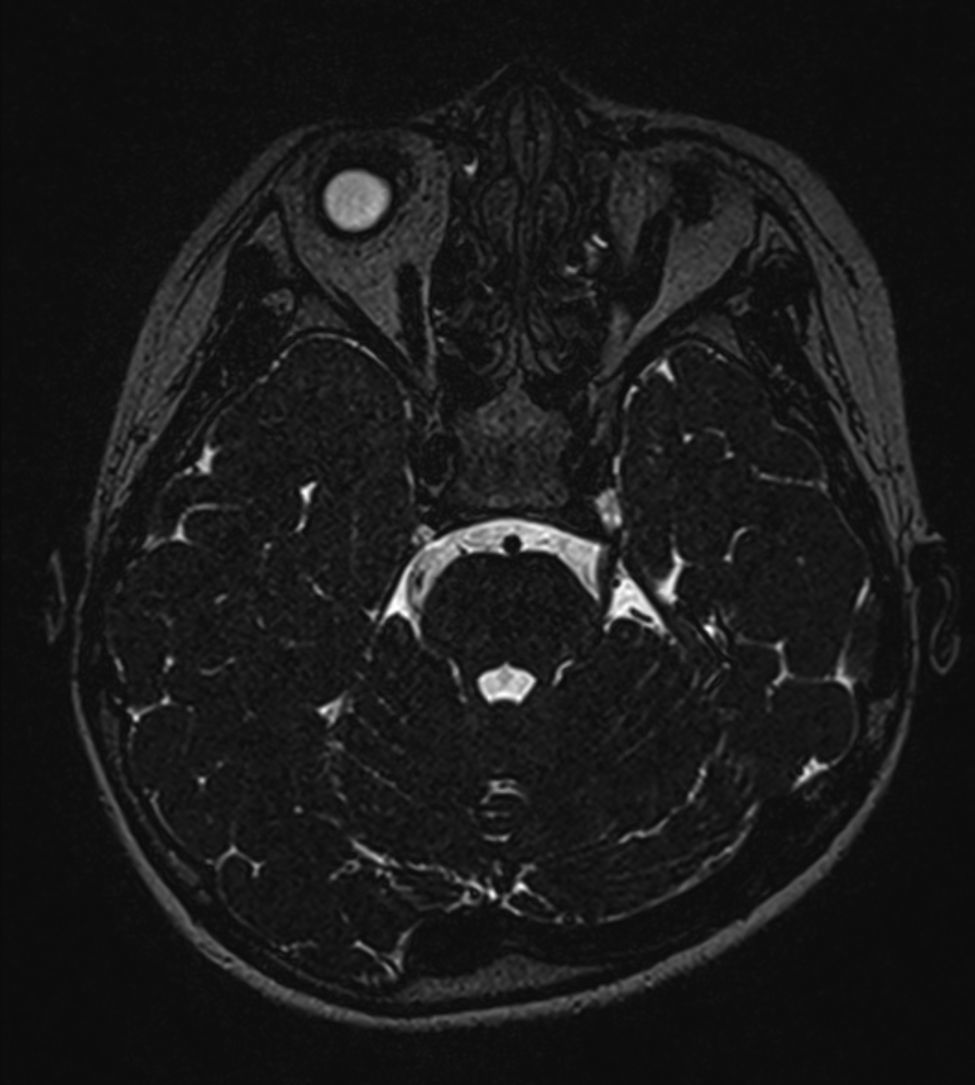

Neurotrophic keratitis is a degenerative disease of the cornea resulting from impaired trigeminal innervation. Prevalence is estimated at fewer than 5 cases per 10000 population. Any noxa affecting the trigeminal nerve at any of its segments (from the nerve nucleus to its branches) may cause the disease. We present the case of a 7-year-old girl with a year-and-a-half long history of chronic right-eye keratitis. Local treatment with ocular lubricants yielded no improvement. A brain MRI performed at another hospital revealed no abnormalities. The ophthalmology department at our hospital detected complete corneal anaesthesia; the patient also reported increased sweating as well as discomfort when combing the hair on the right side of her head. Our patient, a Chinese-born girl, was adopted when she was 10 months old. Her year at school corresponds to her age. The physical examination revealed normal cranial nerve function except for mild right-sided asymmetrical wrinkling. The patient reported asymmetrical superficial tactile perception in her face; tactile perception was normal for the rest of the body. Tests for viral or bacterial infection yielded negative results. We requested a brain MRI scan with sequences centred on the posterior fossa; this revealed right trigeminal nerve and ipsilateral Meckel cave hypoplasia (Fig. 1).

Neurotrophic keratitis is a degenerative disease of the cornea resulting from trigeminal nerve alterations. The resulting lesions range from superficial punctate keratopathy to corneal ulcers or persistent epithelial defects which may lead to stromal melting and corneal perforation.1,2 Any noxa affecting the trigeminal nerve may cause the disease. The most frequent causes of neurotrophic keratitis are herpes simplex virus infection, intracranial lesions, and surgery damaging the trigeminal nerve. Other causes include burns, wounds, corneal dystrophy, long-term use of local anaesthetics, or surgery of the anterior segment of the trigeminal nerve. A number of systemic disorders may also cause alterations in corneal sensitivity (multiple sclerosis, leprosy, etc.), familial dysautonomia, Goldenhar syndrome, Möbius syndrome, familial corneal hypoaesthesia, or congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis.1,3

Physical examination may help locate the lesion. Presence of lagophthalmos suggests involvement of the sixth cranial nerve, whereas ptosis points to a lesion to the second cranial nerve. When the cause of the disease cannot be established clearly, an MRI scan centred on the posterior fossa should be performed to detect brainstem malformations.2–4

There is no specific treatment for neurotrophic keratitis. Current treatment approaches focus on preventing corneal trauma and improving quality and transparency of the cornea. Different treatments can be used depending on lesion progression: local antibiotics, autologous serum, thymosin beta-4 eye drops, topical application of substance P, use of nerve growth factor, etc. Surgery is indicated only in severe cases. Amniotic membrane grafts seem to improve epithelialisation and reduce inflammation.5–9 In conclusion, neurotrophic keratitis is an unusual condition with no specific treatment. It is rarely caused by anatomic lesions; however, brain malformations should be ruled out with neuroimaging studies of the brainstem.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Villena A, Dorronzoro Ramírez E, González García B, Jiménez Martínez J. Queratitis neurotrófica secundaria a malformación cerebral. Neurología. 2017;32:62–63.