Prognosis in epilepsy refers to the probability of either achieving seizure remission (SR), whether spontaneously or using antiepileptic drugs (AED), or failing to achieve control of epileptic seizures (ES) despite appropriate treatment.

Use of AED is recommended after a second unprovoked ES. For a first episode, the decision of whether or not to start drug treatment depends on the risk of recurrence and the advantages or disadvantages of the antiepileptic drug. The main goal of treatment is achieving absence of ES without adverse effects (AE). AED is selected according to epilepsy type and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient.

DevelopmentA PubMed search located articles and recommendations by the most relevant scientific societies and clinical practice guidelines concerning epilepsy prognosis and treatment. Evidence and recommendations are classified according to the prognostic criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2001) and the European Federation of Neurological Societies (2004) for therapeutic actions.

ConclusionsMost newly diagnosed epileptic patients achieve good control over their ES. The majority of the AEDs available at present provide effective control over all types of ES, and choice therefore depends on the patient's individual characteristics. Treatment should be initiated as monotherapy at the lowest effective dose, which in half of all patients provides ES control and is well tolerated. In cases in which the first AED is not effective, alternative therapy should be started, and monotherapy should be employed before combination therapy where possible. The probability of achieving good control over ES decreases with each successive treatment failure.

El pronóstico en la epilepsia implica la probabilidad de alcanzar la remisión de las crisis epilépticas (CE) de forma espontánea o bajo tratamiento con fármacos antiepilépticos (FAE), o no conseguirla a pesar de un tratamiento oportuno.

El tratamiento con FAE es recomendable después de una segunda CE no provocada. Tras una primera CE la decisión de iniciar o no el tratamiento con FAE depende de los riesgos de recurrencia y las ventajas o inconvenientes del tratamiento con FAE. El objetivo del tratamiento es alcanzar la ausencia de CE sin efectos adversos (EA). La selección de los FAE se realiza según tipo de epilepsia y las características demográficas y clínicas del paciente.

DesarrolloBúsqueda de artículos en Pubmed y recomendaciones de las Guías de Práctica Clínica (GPC) y Sociedades Científicas más relevantes referentes a pronóstico de la epilepsia y su tratamiento. Se clasifican las evidencias y recomendaciones según los criterios pronósticos del Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2001) y de la European Federation of Neurological Societies (2004) para las actuaciones terapéuticas.

ConclusionesLa mayoría de pacientes que inician una epilepsia consigue el control de sus CE. La mayoría de los FAE disponibles son útiles para el control de cualquier tipo de CE, su elección depende de las características del paciente. Se debe iniciar el tratamiento en monoterapia y a la menor dosis eficaz del FAE elegido, que suele controlar las CE en la mitad de los pacientes y con buena tolerancia. Ante la falta de eficacia del primer FAE, debe intentarse otra terapia alternativa, a ser posible en monoterapia, antes de instaurar una politerapia. Las posibilidades de control de las CE disminuyen con sucesivos fracasos terapéuticos.

In epilepsy, prognosis depends on multiple probabilities: the likelihood of achieving remission of epileptic seizures (ES), whether spontaneously or by using antiepileptic drugs (AED); the likelihood of sustaining remission over time, even after discontinuing AEDs; and the likelihood of not achieving seizure control, despite providing appropriate treatment.

This article includes a review of the natural history of epilepsy, the efficacy of AEDs for preventing recurrence of a first ES, and the long-term drug treatments used to manage epilepsy.

Natural history of epilepsyThe natural history of untreated epilepsy can be deduced from door-to-door population studies, but their diagnostic certainty is low. Based exclusively on semiological data, these studies are carried out in less-developed countries with poor access to pharmacological treatment. The probability of long-term seizure remission without treatment in some of these countries has been calculated at 41% to 46%.1,2 A Finnish cohort study over a long follow-up time and including a few untreated patients found remission rates of 42% at 10 years and of 52% at 20 years after onset of epilepsy. Population studies have reported spontaneous remission rates ranging between 30% and 50% among patients not receiving treatment (LE I).1–3

Observational epidemiology studies, whether prospective or retrospective, have been carried out in developed countries in patients of all ages, most of whom receive antiepileptic treatment. These studies report sustained remission rates of between 60% and 76% (LE I).2,4–6 Half of the patients who are not treated with AEDs after a first generalised tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) never experience another (LE I).6

Hospital-based studies have also found sustained remission among patients with childhood-onset epilepsy, with rates of 68% to 93%, depending on the duration of the remission time examined (LE I).7,8

Efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in reducing risk of recurrence of a first or subsequent seizureTreatment with AEDs is recommended for both children and adults who experience a second unprovoked ES. At this point, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) considers the patient to have epilepsy.9 After the first ES, however, the decision of whether or not to start AED treatment is more complex. Doctors must consider risk of recurrence, any prognostic factors favouring recurrence, and the advantages and disadvantages of long-term AED treatment. In this situation, the decision must be made with the participation of the patient and/or the family and caregivers.

A meta-analysis of observational studies found that the risk of recurrence of a first ES in 2 years was 36% according to prospective studies and 47% in retrospective studies (LE I and II).10

Multicentre Trial for Early Epilepsy and Single Seizure (MESS), the prospective randomised European study of patients who had experienced a first ES of any type, measured risk of recurrence in the untreated adult and paediatric populations: 39% at 2 years and 51% at 5 years (LE I).11

The First Seizure Trial Group, a prospective randomised Italian multicentre study, found that risk of recurrence of a first unprovoked GTCS was higher among untreated patients (51%) than among those who received treatment (25%) in the first 2 years of the follow-up period (LE I).6

Immediate risk of recurrence in the first few years after an initial ES is higher among untreated patients. Observational studies in general estimate a 2-year recurrence rate of 40% among untreated patients. Between 80% and 90% of the patients who experience recurrence do so within 2 years of the first ES. Nevertheless, the likelihood of developing epilepsy cannot be changed by administering treatment immediately after a first ES (LE I).6,11,12

Overall risk after more than one ES increases with the number of seizures; observational studies report a risk of as much as 70% among untreated patients (LE I).13

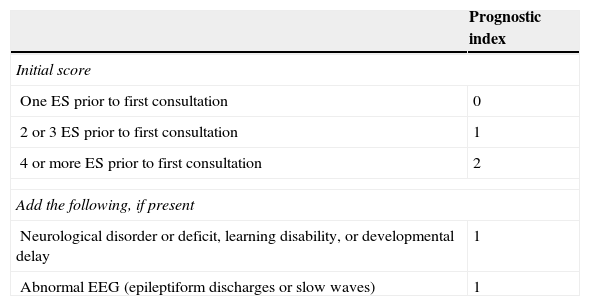

Factors associated with a high risk of recurrence include the type and number of ES, symptom aetiology, anomalies detected in the neurological examination, partial seizures (PS), epileptiform anomalies on the electroencephalogram (EEG), and structural changes in neuroimaging studies (LE II).11,12Table 1 lists the grades on the prognostic index of recurrence given by the MESS study.

Scores on the prognostic index for recurrence from the MESS trial

| Prognostic index | |

|---|---|

| Initial score | |

| One ES prior to first consultation | 0 |

| 2 or 3 ES prior to first consultation | 1 |

| 4 or more ES prior to first consultation | 2 |

| Add the following, if present | |

| Neurological disorder or deficit, learning disability, or developmental delay | 1 |

| Abnormal EEG (epileptiform discharges or slow waves) | 1 |

| Groupings by risk of ES recurrence | Final score |

|---|---|

| Low risk | 0 |

| Moderate risk | 1 |

| High risk | 2-4 |

The following risks should be taken into account when contemplating treatment for a first ES14:

- -

Treatment does not prevent future development of epilepsy

- -

The psychological, social, and legal effects on the patient

- -

Potential adverse effects of the AED, whether neurotoxic, idiosyncratic, teratogenic, or chronic

Risks must be weighed against the following benefits of treatment:

- -

Decreased risk of recurrence

- -

Legal capacity to drive vehicles and engage in certain professional activities

- -

Psychosocial benefits

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) states that treatment with AED is not indicated for preventing the development of epilepsy, and that prescribing AED treatment after the first ES requires weighing the benefits of reduced risk of a second ES against the pharmacological and psychosocial risks of treatment (LE IV).10

Most authors and Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) recommend starting treatment in the following clinical situations (LE III-IV)9,12,15–17:

- -

After 2 or more ES with significant clinical symptoms occurring within a period of 6 to 12 months.

- -

After the first ES, if the patient is at moderate to high risk of recurrence and wishes to begin treatment.

- -

After 2 or more ES with minor symptoms occurring within a longer time period if the patient is at moderate to high risk of recurrence and wishes to begin treatment.

- -

After experiencing status epilepticus (SE), a first GTCS during pregnancy, or unprovoked ES in elderly, disabled, or HIV-positive patients.

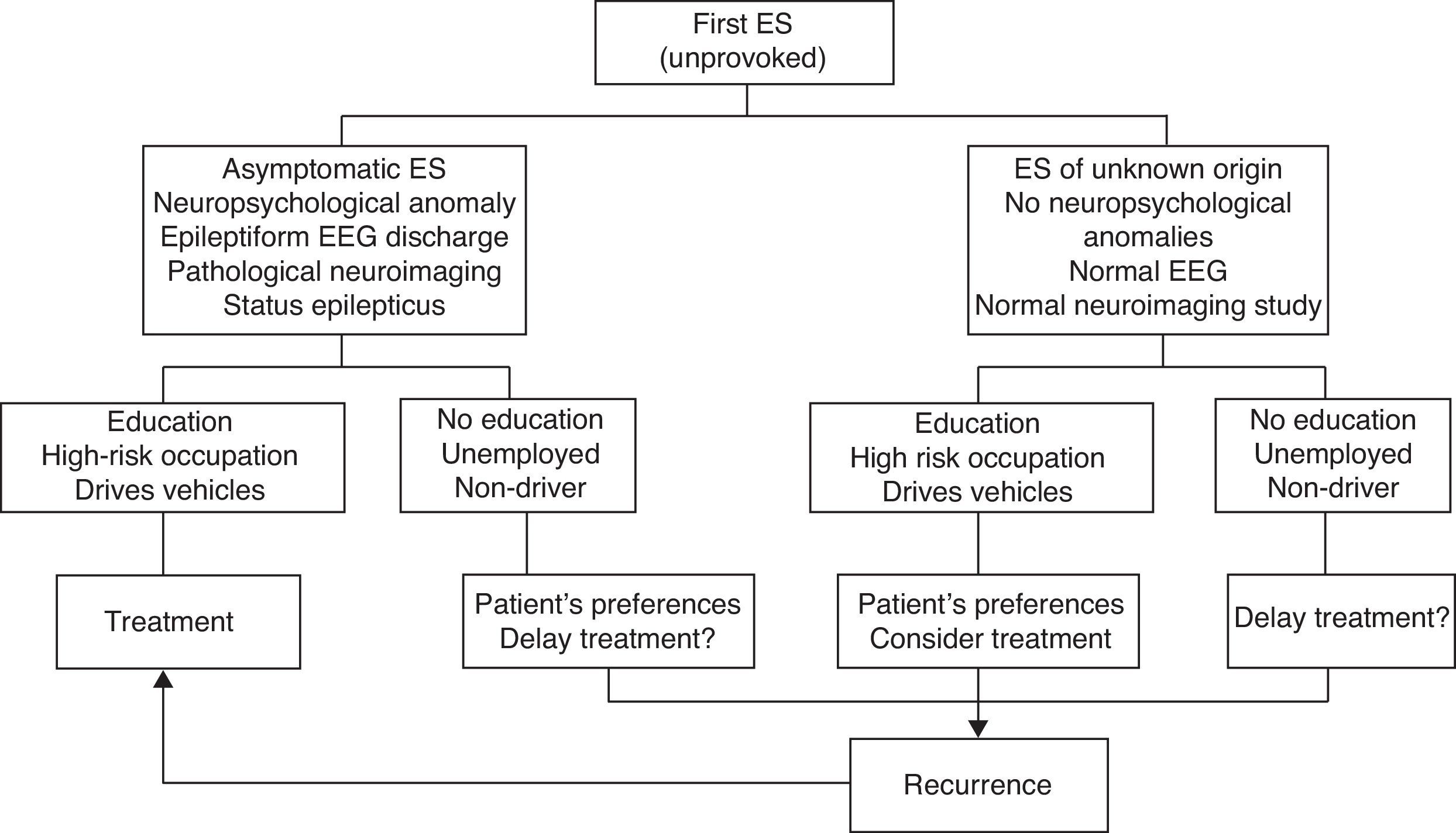

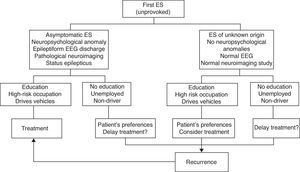

Fig. 1 indicates the therapeutic actions after a first ES as recommended by consensus of the authors of the SEN epilepsy group guidelines (GE-SEN).

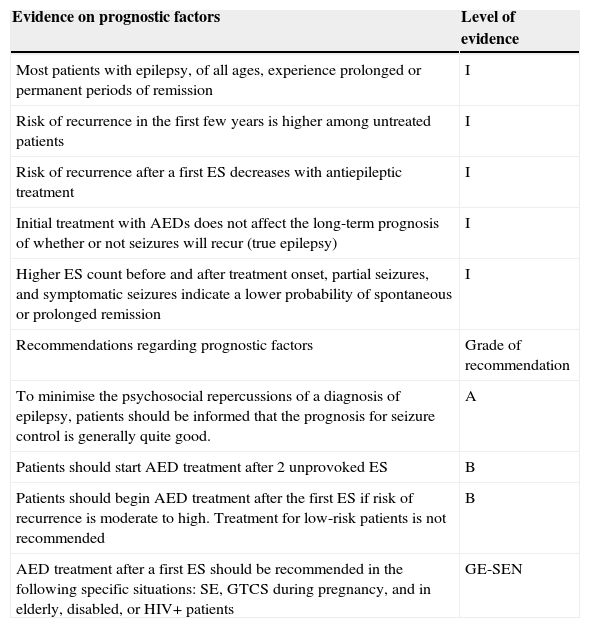

General summary of evidence and recommendations regarding prognostic factors in epilepsy

| Evidence on prognostic factors | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| Most patients with epilepsy, of all ages, experience prolonged or permanent periods of remission | I |

| Risk of recurrence in the first few years is higher among untreated patients | I |

| Risk of recurrence after a first ES decreases with antiepileptic treatment | I |

| Initial treatment with AEDs does not affect the long-term prognosis of whether or not seizures will recur (true epilepsy) | I |

| Higher ES count before and after treatment onset, partial seizures, and symptomatic seizures indicate a lower probability of spontaneous or prolonged remission | I |

| Recommendations regarding prognostic factors | Grade of recommendation |

| To minimise the psychosocial repercussions of a diagnosis of epilepsy, patients should be informed that the prognosis for seizure control is generally quite good. | A |

| Patients should start AED treatment after 2 unprovoked ES | B |

| Patients should begin AED treatment after the first ES if risk of recurrence is moderate to high. Treatment for low-risk patients is not recommended | B |

| AED treatment after a first ES should be recommended in the following specific situations: SE, GTCS during pregnancy, and in elderly, disabled, or HIV+ patients | GE-SEN |

The purpose of AED treatment is to achieve absence of ES without adverse events. Doctors must select the most appropriate type of AED according to type of epilepsy and the patient's characteristics (age, sex, weight, comorbidities, etc.). Although very few studies have compared monotherapy to polytherapy approaches, clinical experience shows that treatment with a single AED provides effective seizure control in most patients, while also promoting compliance and decreasing the likelihood of adverse effects.18–25

Evidence regarding epileptic seizure treatment in adultsWe have reviewed LE-based recommendations from the listed medical societies and/or findings from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews.

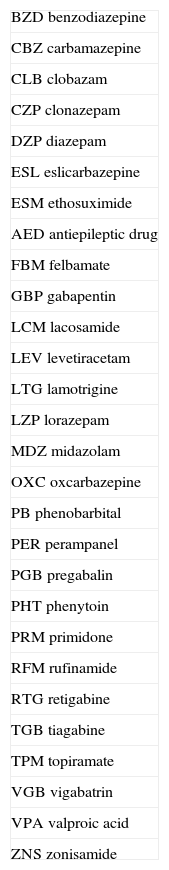

Abbreviations of AEDs are listed in Table 2.

- -

Veterans Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Study. 1985-1992 (PHT, CBZ, VPA, PB, PRM).18,19

- -

ILAE. 2006. Systematic review of initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes (CBZ, PHT, PB, PRM, VPA, VGB, CZP, GBP, LTG, OXC, TPM)20.

- -

American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Epilepsy Society. 2004. Initial systematic review of monotherapy (GBP, LTG, TPM, OXC) and treatment of refractory epilepsy (GBP, LTG, TPM, TGB, OXC, LEV, ZNS).21,22

- -

SANAD: Standard and New Antiepileptic Drugs. 2007. Non-blinded RCT (CBZ, VPA, GBP, LTG, OXC, TPM).23,24

- -

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2012. CPGs for management of the epilepsies in adults and children.16

- -

Andalusian Epilepsy Society. Guía Andaluza de Epilepsia 2009.17

- -

ILAE. 2013. Updated systematic review of initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes.25 LEV and ZNS added to study.

Abbreviations of antiepileptic drugs

| BZD benzodiazepine |

| CBZ carbamazepine |

| CLB clobazam |

| CZP clonazepam |

| DZP diazepam |

| ESL eslicarbazepine |

| ESM ethosuximide |

| AED antiepileptic drug |

| FBM felbamate |

| GBP gabapentin |

| LCM lacosamide |

| LEV levetiracetam |

| LTG lamotrigine |

| LZP lorazepam |

| MDZ midazolam |

| OXC oxcarbazepine |

| PB phenobarbital |

| PER perampanel |

| PGB pregabalin |

| PHT phenytoin |

| PRM primidone |

| RFM rufinamide |

| RTG retigabine |

| TGB tiagabine |

| TPM topiramate |

| VGB vigabatrin |

| VPA valproic acid |

| ZNS zonisamide |

AEDs are primarily authorised for a specific type of ES for which they have been proved effective by RCTs. On rare occasions, they are authorised for epileptic syndromes based on studies with poor methodological quality.

All classic AEDs have been demonstrated effective for secondarily generalised partial seizures and primary GTCS (LE I).18,19 CBZ, PHT, and VPA are better tolerated than are barbiturates (PB, PRM) (LE I).18,19

RCTs have shown that all of the new AEDs are effective as adjunct therapy for partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation. Some drugs (GBP, LEV, LTG, OXC, TPM, ZNS) have also been validated as monotherapy (LE I).16,17,22,25

Some of the new AEDs (TPM, OXC, LTG) are also effective against primary GCTS (LE III),20,24 and LTG is effective for absence seizures (LE III).

Clinical practice has shown that CBZ, GBP, OXC, PGB, TGB, VGB, PHT, and LTG can provoke or exacerbate generalised absence and/or myoclonic seizures (LE IV).16,17

Trials with new RTG treatments were recently suspended due to severe idiosyncratic adverse effects impacting the skin and eyes.

A new ADE, perampanel (PER), was approved as adjunct therapy for refractory partial seizures.26

Variables considered when selecting an AED for patients recently diagnosed with epilepsy should include such drug characteristics as specificity for the type of seizure, efficacy spectrum, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, interactions, types of presentation, titration rate, and number of doses per day. Patient-related variables should include genetic studies, age, comorbidities, and any other treatments.

The first-choice drug is the one with the greatest probability of being effective and the lowest probability of adverse effects; the correct dose is the lowest to achieve ES control without adverse effects.

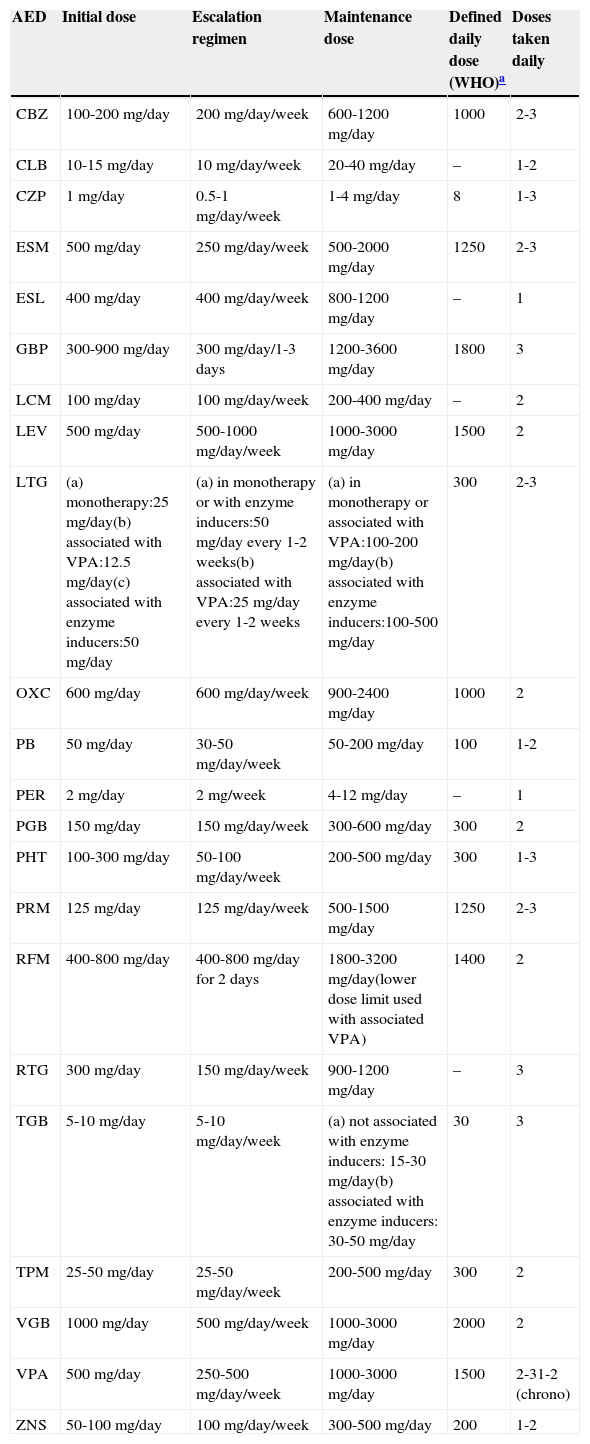

Table 3 shows the initial doses, temporary dose scaling recommendations, and normal AED maintenance doses.

Standard oral doses of AEDs in adults

| AED | Initial dose | Escalation regimen | Maintenance dose | Defined daily dose (WHO)a | Doses taken daily |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBZ | 100-200mg/day | 200mg/day/week | 600-1200mg/day | 1000 | 2-3 |

| CLB | 10-15mg/day | 10mg/day/week | 20-40mg/day | – | 1-2 |

| CZP | 1mg/day | 0.5-1mg/day/week | 1-4mg/day | 8 | 1-3 |

| ESM | 500mg/day | 250mg/day/week | 500-2000mg/day | 1250 | 2-3 |

| ESL | 400mg/day | 400mg/day/week | 800-1200mg/day | – | 1 |

| GBP | 300-900mg/day | 300mg/day/1-3 days | 1200-3600mg/day | 1800 | 3 |

| LCM | 100mg/day | 100mg/day/week | 200-400mg/day | – | 2 |

| LEV | 500mg/day | 500-1000mg/day/week | 1000-3000mg/day | 1500 | 2 |

| LTG | (a) monotherapy:25mg/day(b) associated with VPA:12.5mg/day(c) associated with enzyme inducers:50mg/day | (a) in monotherapy or with enzyme inducers:50mg/day every 1-2 weeks(b) associated with VPA:25mg/day every 1-2 weeks | (a) in monotherapy or associated with VPA:100-200mg/day(b) associated with enzyme inducers:100-500mg/day | 300 | 2-3 |

| OXC | 600mg/day | 600mg/day/week | 900-2400mg/day | 1000 | 2 |

| PB | 50mg/day | 30-50mg/day/week | 50-200mg/day | 100 | 1-2 |

| PER | 2mg/day | 2mg/week | 4-12mg/day | – | 1 |

| PGB | 150mg/day | 150mg/day/week | 300-600mg/day | 300 | 2 |

| PHT | 100-300mg/day | 50-100mg/day/week | 200-500mg/day | 300 | 1-3 |

| PRM | 125mg/day | 125mg/day/week | 500-1500mg/day | 1250 | 2-3 |

| RFM | 400-800mg/day | 400-800mg/day for 2 days | 1800-3200mg/day(lower dose limit used with associated VPA) | 1400 | 2 |

| RTG | 300mg/day | 150mg/day/week | 900-1200mg/day | – | 3 |

| TGB | 5-10mg/day | 5-10mg/day/week | (a) not associated with enzyme inducers: 15-30mg/day(b) associated with enzyme inducers: 30-50mg/day | 30 | 3 |

| TPM | 25-50mg/day | 25-50mg/day/week | 200-500mg/day | 300 | 2 |

| VGB | 1000mg/day | 500mg/day/week | 1000-3000mg/day | 2000 | 2 |

| VPA | 500mg/day | 250-500mg/day/week | 1000-3000mg/day | 1500 | 2-31-2 (chrono) |

| ZNS | 50-100mg/day | 100mg/day/week | 300-500mg/day | 200 | 1-2 |

Patients should first be treated with a single AED (initial monotherapy) at the lowest effective dose to minimise the risk of adverse effects and facilitate treatment compliance. In one prospective observational study, almost half of all patients recently diagnosed with epilepsy at any age, with any type of ES or aetiology, remained seizure-free as a result of the first AED administered; in this group, more than 90% remained seizure-free while on low doses. Among patients who did not respond to the first AED without adverse effects, the probability of seizure control decreased with each successive attempt at treatment (LE II).27

Another prospective observational study of a newly diagnosed patient cohort and their treatment response patterns found that at the time of their most recent outpatient visit, 68% had been seizure-free for more than a year and 62% were being treated with a single AED. Treatment responses were divided into 4 groups: early and sustained seizure freedom (37%); delayed but sustained seizure freedom (22%); fluctuation between periods of seizure freedom and relapse (16%); and seizure freedom never attained (25%) (LE II).28

The initially selected AED should be discontinued if unacceptable adverse effects appear, ES continues, or new ES are provoked by the treatment. In any of these cases, patients should be switched to a different AED with better prospects for a good response.

Nevertheless, one RCT in a randomised sample of patients with cryptogenic or symptomatic partial epilepsy treated in monotherapy with an alternative AED, or in bitherapy with a second AED, found no differences between the two groups regarding either ES control or adverse effects during one year of follow-up.29 If the initial monotherapy is not effective, most authors and CPGs recommend trying an alternative drug in monotherapy prior to starting bitherapy.

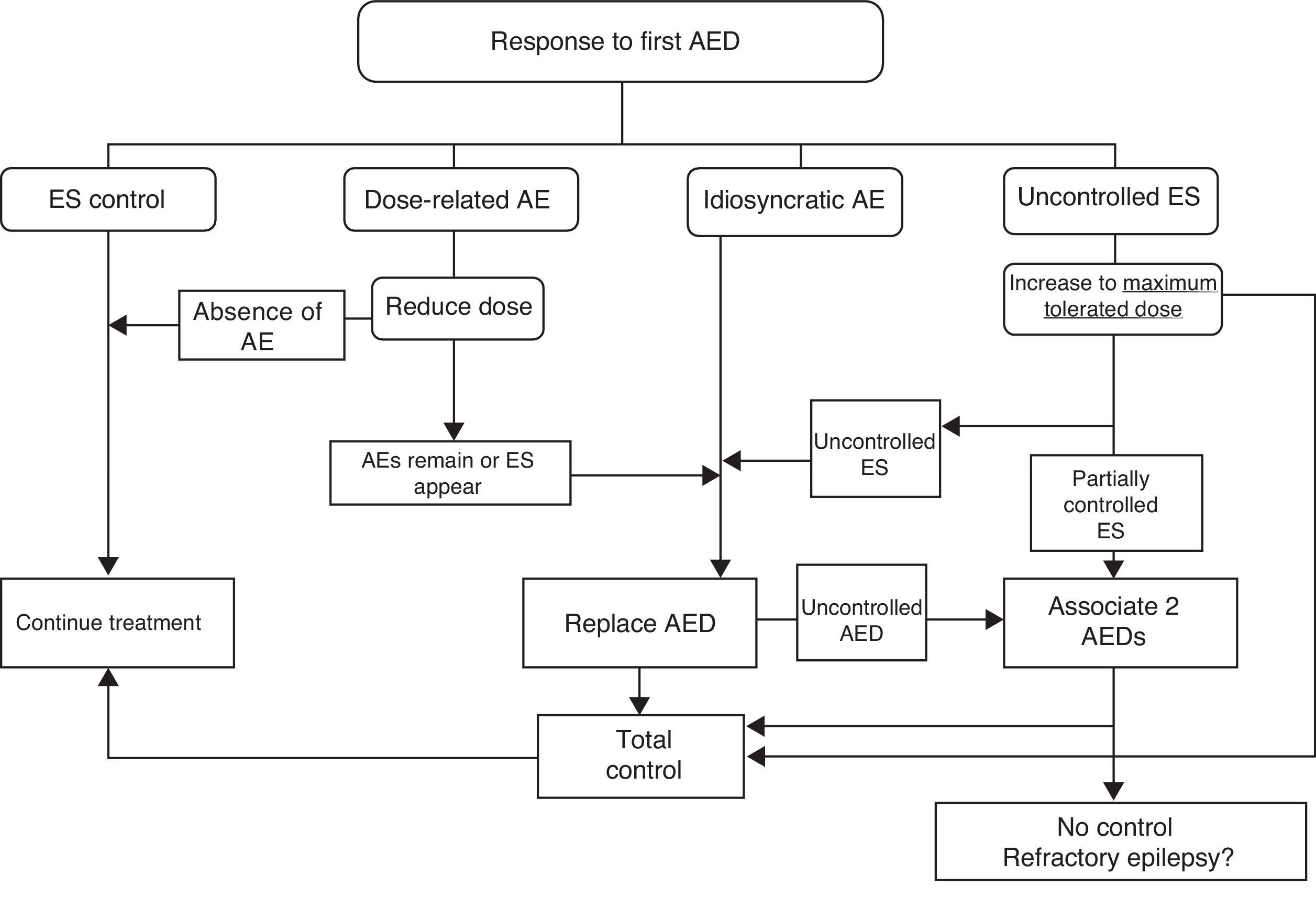

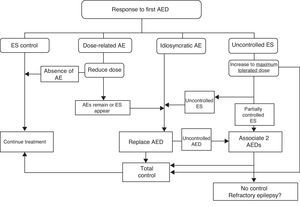

If ES remain uncontrolled after trying two drugs in monotherapy, authors recommend trying combinations of FAEs with proved efficacy for the type of ES and which are unlikely to cause adverse effects. Fig. 2 lists therapeutic actions for possible responses to initial drug treatment according to consensus among authors of the GE-SEN guidelines.

Adjusting treatment to the patient's individual characteristics, whether or not that treatment follows published recommendations, is a prerogative that doctors should not sacrifice.30

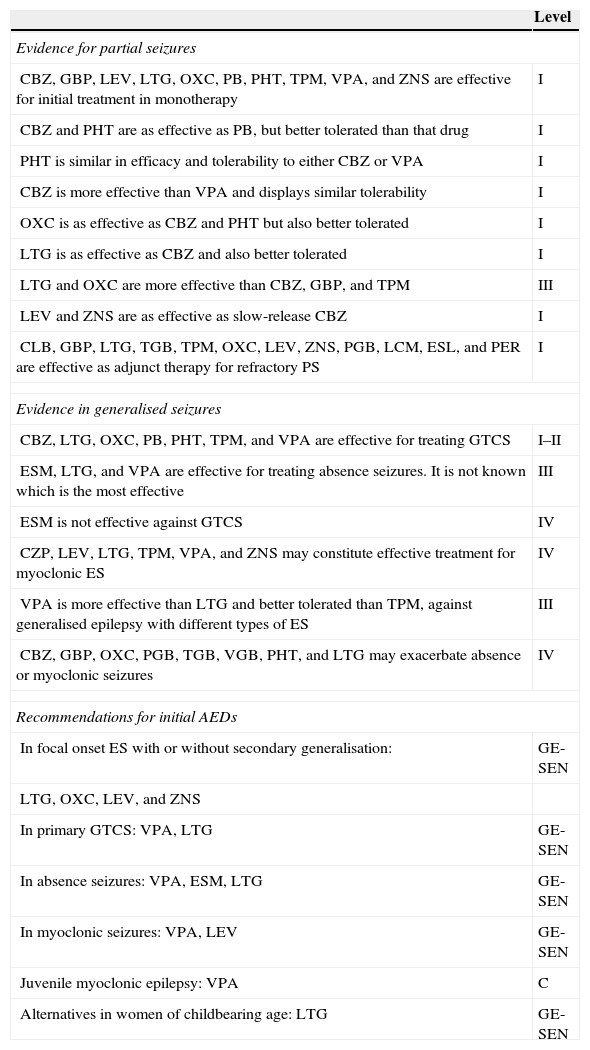

General list of evidence and recommendations on long-term pharmacological treatment of epilepsy in adults

| Level | |

|---|---|

| Evidence for partial seizures | |

| CBZ, GBP, LEV, LTG, OXC, PB, PHT, TPM, VPA, and ZNS are effective for initial treatment in monotherapy | I |

| CBZ and PHT are as effective as PB, but better tolerated than that drug | I |

| PHT is similar in efficacy and tolerability to either CBZ or VPA | I |

| CBZ is more effective than VPA and displays similar tolerability | I |

| OXC is as effective as CBZ and PHT but also better tolerated | I |

| LTG is as effective as CBZ and also better tolerated | I |

| LTG and OXC are more effective than CBZ, GBP, and TPM | III |

| LEV and ZNS are as effective as slow-release CBZ | I |

| CLB, GBP, LTG, TGB, TPM, OXC, LEV, ZNS, PGB, LCM, ESL, and PER are effective as adjunct therapy for refractory PS | I |

| Evidence in generalised seizures | |

| CBZ, LTG, OXC, PB, PHT, TPM, and VPA are effective for treating GTCS | I–II |

| ESM, LTG, and VPA are effective for treating absence seizures. It is not known which is the most effective | III |

| ESM is not effective against GTCS | IV |

| CZP, LEV, LTG, TPM, VPA, and ZNS may constitute effective treatment for myoclonic ES | IV |

| VPA is more effective than LTG and better tolerated than TPM, against generalised epilepsy with different types of ES | III |

| CBZ, GBP, OXC, PGB, TGB, VGB, PHT, and LTG may exacerbate absence or myoclonic seizures | IV |

| Recommendations for initial AEDs | |

| In focal onset ES with or without secondary generalisation: | GE-SEN |

| LTG, OXC, LEV, and ZNS | |

| In primary GTCS: VPA, LTG | GE-SEN |

| In absence seizures: VPA, ESM, LTG | GE-SEN |

| In myoclonic seizures: VPA, LEV | GE-SEN |

| Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: VPA | C |

| Alternatives in women of childbearing age: LTG | GE-SEN |

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mercadé Cerdá JM, Mauri Llerda JA, Becerra Cuñat JL, Parra Gomez J, Molins Albanell A, Viteri Torres C, et al. Pronóstico de la epilepsia. Inicio del tratamiento crónico farmacológico. Neurología. 2015;30:367–374.