Osteoclastoma or giant cell tumour of bone is an osteolytic neoplasm which accounts for only 5% of all bone tumours. It usually arises in the epiphysis of long bones and may very rarely be found on the spinal column above the sacrum, with an incidence of about 2.5% in a large series of cases.1 Only anecdotal cases of osteoclastomas originating in the ribs have been described.2 This tumour is slightly predominant in women and the most frequent age of tumour onset is between 20 and 40 years. Despite being benign, they can be very aggressive locally; tumours may recur if complete resection is not achieved, and there have even been published cases of metastasis.3

The histology of this tumour is characterised by multinucleated giant cells in a background of mononuclear and spindle-shaped cells.

Clinical presentation of osteoclastoma in the spinal column consists of pain4; there may also be radicular symptoms and, more rarely, varying degrees of paraplegia due to spinal cord compression.3–5

We present the case of a 16-year-old boy with no relevant personal or family history. Over a period of 2 months, he had experienced progressive symptoms of weakness in the legs with a dull, mild ache in the medial spinal column. Over the last 2 weeks, weakness had increased, which had caused the patient to fall on several occasions. Weakness was associated with urinary urgency with decreased sensation in the legs extending to the lower thorax. Neurological examination showed cortical functions and cranial nerve pairs to be normal. Assessment of motor functions revealed mild lower limb spasticity, global and symmetrical muscle strength of 4/5 in lower extremities, hyperreflexia, ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski signs. Hypoesthesia was present up to the D8 level. Gait showed mild paraparesis and ataxia due to sensory deficit in posterior funiculi.

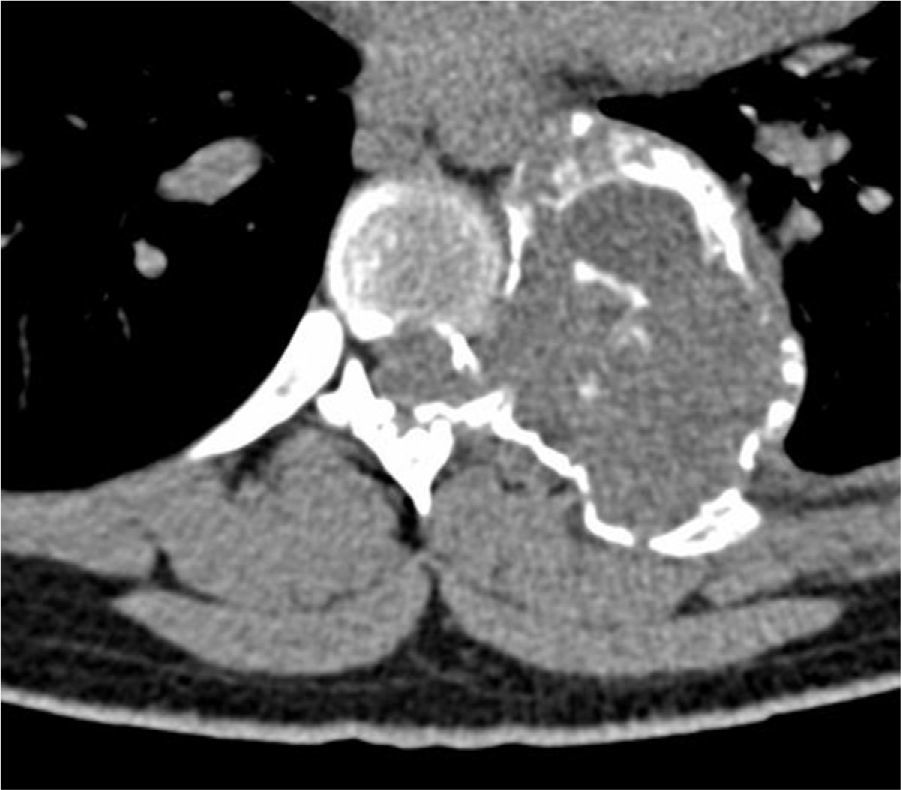

On the spine CT (Fig. 1), we observed an osteolytic tumour lesion seated on the posterior arch of the left seventh rib. The lesion was destroying the pedicle and the posterior part of the D7 vertebral body. MRI scan (Fig. 2) revealed a homogeneous, multicystic lesion with no contrast uptake extending from the posterior arch of the left seventh rib towards the chest and spinal canal, thereby compressing the spine at that level.

The patient underwent surgery under general anaesthesia and with support from vascular surgeons. The left sixth, seventh, and eighth ribs were resected and D7 vertebral body was partially resected, including the lamina and pedicle. The entire extra- and intrathecal tumour mass was removed. Surgeons then performed interbody arthrodesis with vertebral body replacement using a plate and screws (D6-D8). Anatomical pathology study of the lesion showed nodular tissue adhering to a rib fragment and measuring 6cm in diameter at its widest point. Serial slices showed the tissue to be multicystic. Analysis of the tumour revealed a biphasic pattern with multinucleated giant cells and spindle-shaped stromal cells lacking atypical features, consistent with osteoclastoma.

Clinical outcome has been positive and neurological symptoms disappeared with no relapses in 4 years of follow-up.

Radiological appearance of osteoclastomas is relatively non-specific and differential diagnosis must rule out aneurysmal bone cyst, osteosarcoma, brown tumour of hyperparathyroidism, and carcinoma metastasis.4 From the histological viewpoint, osteoclastoma can resemble Paget disease of bone.6

Surgical treatment for osteoclastoma is commonly aggressive, given that tumours are locally invasive and their course is unpredictable. The global risk of recurrence for this type of spinal tumour is between 25% and 45%.1,7 Partial resection, location in the cervical spine, male sex, age younger than 25 years, and local radiation are considered risk factors for tumour recurrence.3 Use of adjuvant radiotherapy in osteoclastomas is controversial due to the risk of malignant transformation into sarcoma.1,6,8

Resection of a tumour is generally associated with obvious remission of neurological symptoms of spinal cord compression given that this tumour exerts pressure but does not infiltrate.9 Incomplete resection has sometimes caused major sequelae.10

Our case, in addition to providing exceptional findings, highlights the differential diagnosis necessary in cases of osteolytic bone lesions. It also shows how benign lesions, such as osteoclastoma, can cause important neurological symptoms that can elicit significant sequelae if doctors do not indicate an appropriate diagnosis and aggressive treatment.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez Caballero PE. Paraparesia progresiva como forma de presentación de un osteoclastoma del arco posterior de una costilla. Neurología. 2014;29:316–318.