Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is the most common prion disease in humans. It is caused by accumulation of abnormally folded prion proteins in the central nervous system. By aetiology, it is classified as sporadic, acquired, or genetic.1 Between 10% and 15% of cases are caused by mutations in the prion protein gene (PRNP), with E200K being the most common mutation. The disease manifests with rapidly progressive cognitive impairment, cerebellar signs, and myoclonus, and presents a progressive fatal course. Seizures are reported in less than 15% of sporadic cases of CJD.2,3

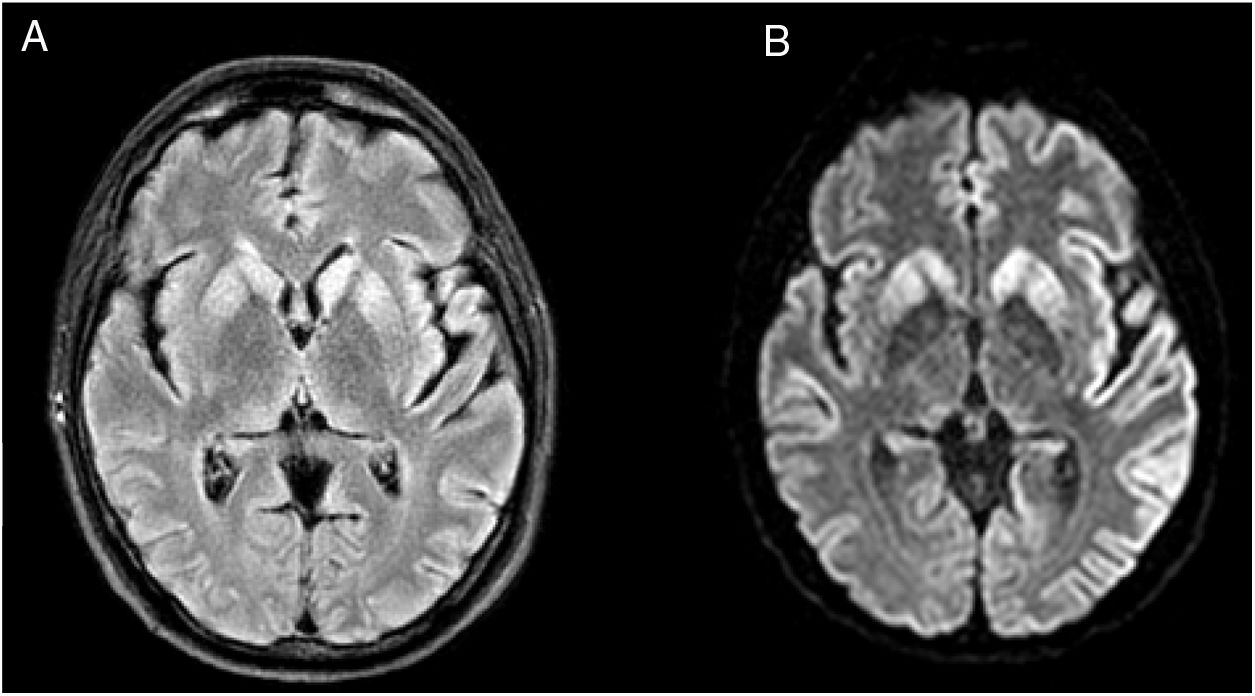

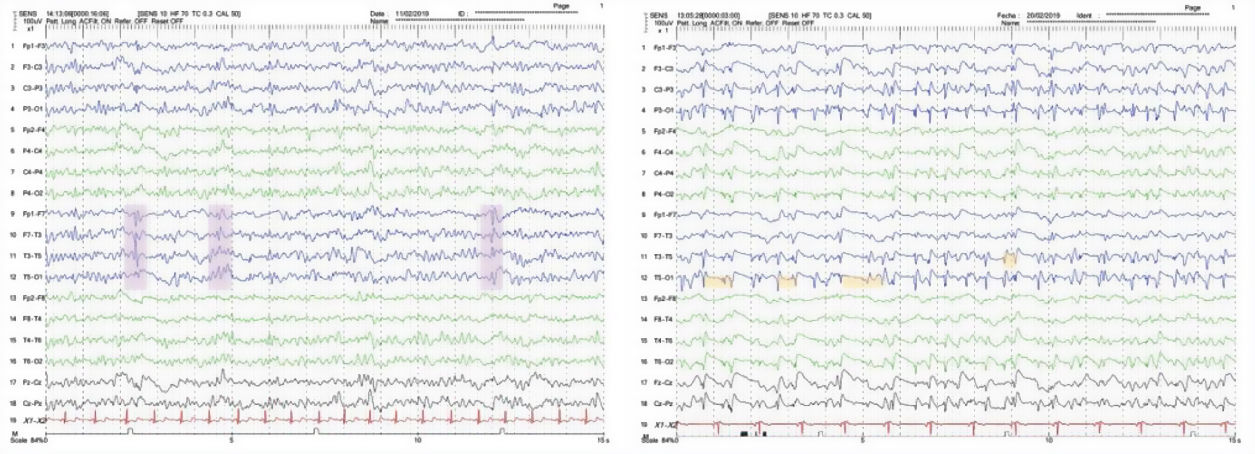

We present the case of a 48-year-old white man with personal history of arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and chronic tobacco and cannabis use. He had no relevant family history or prior treatments. The patient was admitted due to speech and gait alterations of 2 months’ progression. At admission, he presented predominantly motor aphasia and gait ataxia. Physical examination identified dysphasia, disinhibited behaviour with psychomotor agitation and unprovoked laughter, bilateral grasping reflex, dystonia in the left hand, dysmetria in the upper limbs, stimulus-induced multifocal myoclonus, and cerebellar ataxia. A complete blood analysis including serology and autoimmunity studies revealed no pathological findings. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was acellular with slightly elevated protein levels; microbiological findings were negative and a 14-3-3 assay was positive. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed FLAIR hyperintensity in both caudate nuclei and diffusion restriction in the putamina, both caudate nuclei, frontal and temporal parasagittal areas, and both cingulate gyri, with left predominance (Fig. 1). On the third day after admission the patient presented an episode of tonic ocular deviation to the right and altered level of consciousness, of 2-3 minutes’ duration, which suggested a secondarily generalised focal seizure. During the first 2 weeks after admission, 6 electroencephalography (EEG) studies were performed, revealing pseudoperiodic discharges of generalised, predominantly left biphasic and triphasic sharp waves with spikes/polyspikes (Fig. 2). Despite antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam at 2000 mg/24 hours, on day 11 he presented secondarily generalised status epilepticus with EEG correlate, which was responsive to clonazepam. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, and progressed poorly despite treatment with multiple antiepileptics (levetiracetam, lacosamide, phenytoin, clonazepam, midazolam, and propofol) and immunomodulation with corticosteroids and immunoglobulins. Genetic testing for CJD confirmed homozygous presence of the E200K mutation of the PRNP gene, with methionine at codon 129 (MM genotype). The patient died 3 weeks after admission. The neuropathological examination showed widespread vacuolisation and transcortical astrocytosis, which were particularly intense in limbic regions and the temporal neocortex; these findings are compatible with diagnosis of CJD.

The clinical presentation, with rapidly progressive cognitive impairment and ataxia, multifocal myoclonus, and focal dystonia, led us to suspect a prion encephalopathy as the most likely diagnosis. Differential diagnosis included autoimmune encephalitis, infectious encephalitis, toxic/deficiency and metabolic encephalopathies, vasculitis, and leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Due to the episode of status epilepticus, we considered the possibility of autoimmune encephalitis, after ruling out herpes simplex encephalitis, and started empirical treatment with corticosteroids and immunoglobulins. In addition to the characteristic clinical presentation and rapid progression, one of the key clinical findings prompting suspicion of CJD was the presence of myoclonus.

CJD is a rare neurodegenerative disease; diagnosis of probable CJD is based on clinical, EEG, neuroimaging, and laboratory findings. The genetic form follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. However, as in our patient’s case, more than 60% of patients with genetic CJD do not have family history of the condition.4,5 For this reason, diagnosis of genetic CJD can be challenging.

In early stages of the disease, EEG findings may be normal or pathological, with non-specific diffuse theta or delta rhythm, frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA), or periodic lateralised epileptiform discharges (PLED). The characteristic periodic sharp-wave complexes (PSWC) appear in 66% of patients with sporadic CJD and in 10% of patients with genetic CJD, usually in advanced stages.6 PSWCs correlate with cortical involvement observed in MRI studies, which is more common in sporadic forms.7 Status epilepticus has been reported in few cases of sporadic CJD8 and in only 2 cases of familial CJD.9,10

Our patient had genetic CJD in the absence of family history, and presented an episode of status epilepticus, which is unusual in sporadic CJD, and even rarer in the genetic form. Although the typical PSWCs did not appear on the EEG, the performance of multiple EEGs enabled us to identify pseudoperiodic biphasic and triphasic sharp-wave complexes, which are highly suggestive of CJD, despite not being considered a diagnostic criterion. The significant temporal cortex involvement observed in the MRI study and confirmed in the neuropathological examination may explain the seizures and therefore the rapid progression.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the phenotypic variability of CJD: it is one of the few reported cases of refractory focal status epilepticus in a patient with genetic CJD. Finally, we should stress the importance of performing serial EEG and genetic studies when a prion disease is suspected.

Presentations at congressesThis study was presented at the 71st Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.

FundingThis study has received no public or private funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Roldós A, Esteban de Antonio E, Pérez-Chirinos Rodríguez M, Pérez Sánchez JR. Status epiléptico refractario en enfermedad de Creutzfeldt-Jakob genética por mutación E200K. Neurología. 2020;35:712–714.