Aerial, arterial or venous embolisms are usually a complication derived from invasive medical procedures.1,2 One of the most common causes of aerial venous embolism is the insertion, maintenance or removal of a central venous catheter (CVC).3,4 The entry of air may occur if central venous pressure is less than atmospheric pressure, a condition that occurs in the superior vena cava when patients have an elevated chest position or during Valsalva manoeuvres.5 The neurological symptoms due to air embolism are non-specific and include altered level of consciousness, comitial seizures and stroke.6

We describe the case and neuroimaging of a patient with ischaemic stroke due to air embolism during manipulation of a CVC.

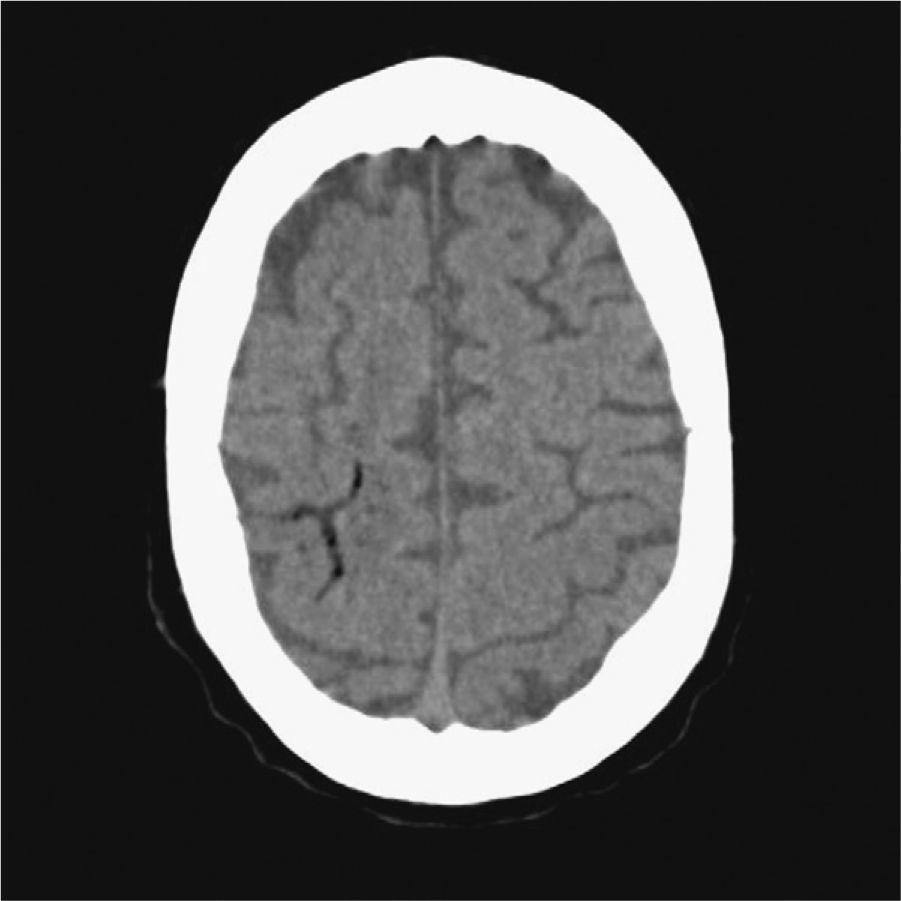

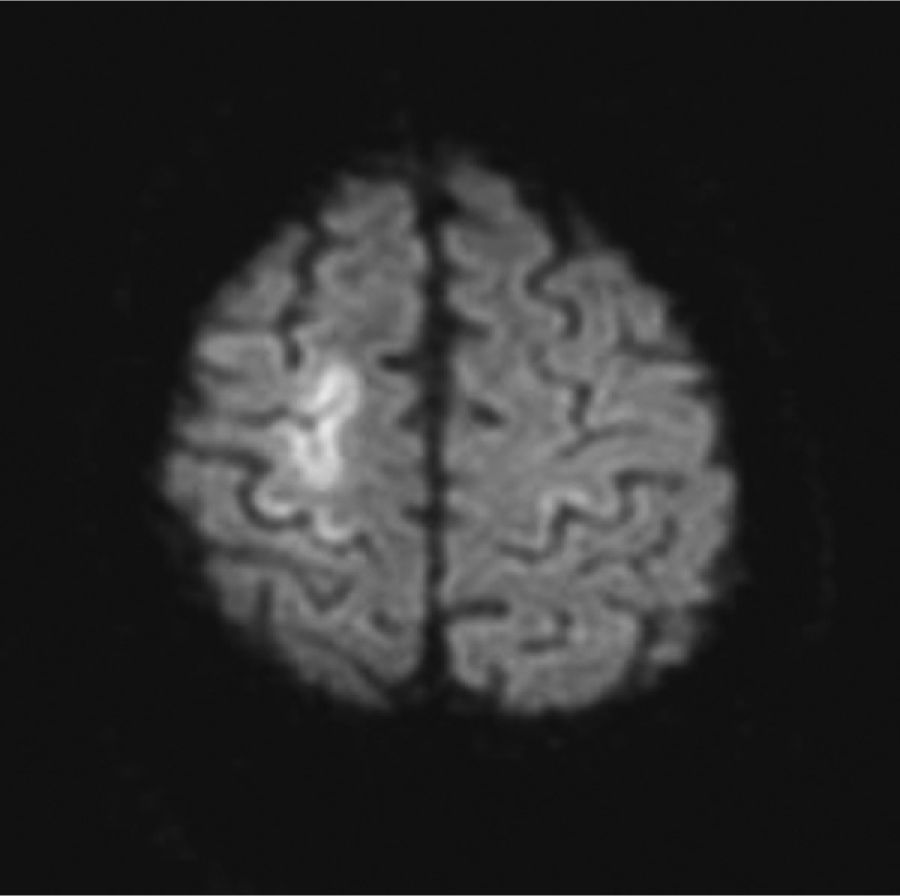

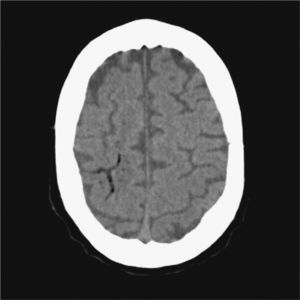

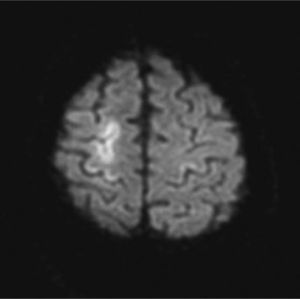

The patient was a 76-year-old male admitted due to acute renal failure in the context of an anaphylactic reaction which required the placement of a right, central, venous jugular catheter to perform haemodialysis. Immediately after removal of the catheter, which was performed in a sitting position, the patient suffered a sudden loss of consciousness with conjugate gaze deviation to the right side and tetraparesis. Neither hypotension nor hypoxia was detected. An urgent cranial CT scan (Fig. 1), obtained 1h after onset of symptoms, revealed areas of hypodensity in the right superficial cortical veins and extensive collections of gas in the right jugular vein, in both cavernous sinuses (Fig. 2) and in subcutaneous structures. No images of acute ischaemia were found in the diffusion sequences of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed 30min later. The patient presented gradual clinical improvement with persistence of paresis of the left upper limb. A cranial MRI at 72h (Fig. 3) revealed restriction areas in diffusion sequences and hyperintense areas in T2 sequences located in the cortical sulci where gas bubbles had previously been observed, suggestive of venous stroke. A transesophageal echocardiogram and a transcranial Doppler with air-saline contrast did not show the presence of right-to-left shunt.

At the systemic level, the haemodynamic manifestations of a venous embolism are attributed to the massive inflow of air at the level of the right ventricle and the pulmonary circulation, leading to hypoxia with pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular failure, arrhythmias and cardiac failure.1,2 Cerebral ischaemic lesions due to venous air embolism may be secondary to paradoxical embolism by air with entry to the venous circuit and passage to the arterial circuit through a cardiac or pulmonary right-to-left shunt, or through massive venous air embolism overflowing the pulmonary filter. Exceptional cases with a retrograde venous mechanism have also been described.7,8 Recent research has shown that an air embolism through a standard venous catheter has a high possibility of ascending through a retrograde pathway by the venous circulation, depending on the size of the bubbles, the diameter of the catheter and the ejection fraction.9,10 Air embolism ischaemia is caused by several mechanisms: obstruction of blood flow, vasospasm and thrombus formation by platelet activation. The temporal relationship between the procedure and the stroke facilitates its diagnostic suspicion. Neuroimaging tests must be carried out immediately to detect the presence of gas; there is a predilection for frontal cortical involvement and especially for the border areas of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries.11 Upon suspicion of retrograde air embolism, patients must be placed in the Trendelenburg position and in the left lateral decubitus position, with the aim of promoting the return of the bubbles to the central venous circulation. Oxygen should be administered both to treat hypoxia and to eliminate the gas by establishing a diffusion gradient. There have been various reports with good prognosis after receiving hyperbaric oxygen, and it has been proposed as the treatment of choice.12,13

This case illustrates the pathophysiological mechanism of a retrograde venous pathway due to the presence of air in cervical and cranial venous structures, the absence of proven left–right shunt and the onset of cerebral venous stroke in the cortical folds in whose veins there was air detected in the early neuroimaging scans.

Air embolism must be suspected in patients with unexplained cardiovascular or neurological symptoms and CVC. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential. The retrograde venous mechanism should be considered in patients without right-to-left shunt.