The Foix-Chavany-Marie syndrome (FCMS) or anterior opercular syndrome is characterised by loss of voluntary movement of the orofacial and pharyngeal muscles, with preserved automatic and reflex movements,1 secondary to bilateral lesions to the anterior opercular cortex; however, cases of unilateral involvement or bilateral subcortical lesions have also been reported.2 The most frequent aetiology is vascular,3 but the syndrome may also be of infectious, demyelinating, traumatic, neoplastic, epileptic, or neurodegenerative origin.4 We describe a case secondary to herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) encephalitis.

Our patient was a 27-year-old, right-handed woman with history of untreated autoimmune thyroiditis, who presented a 2-month history of progressive bilateral facial weakness predominantly affecting the left side, inability to speak due to anarthria and severe hypophonia, and swallowing difficulties together with severe mixed dysphagia and sialorrhoea. In the previous 24 hours, she had presented 3 episodes suggestive of focal seizures, of 5 min duration each: the first episode consisted of tonic rigidity of the upper limbs preceded by snoring during sleep; in the second episode, she presented jaw rigidity and globus sensation; the third episode consisted of left facial clonic movements.

The general examination revealed no relevant data. The neurological examination revealed a loss of voluntary movement in the muscles of the face, tongue, and pharynx, with preservation of the reflex blink to visual threat, automatic facial mimicry, and gag and coughing reflexes; these findings are compatible with FCMS.

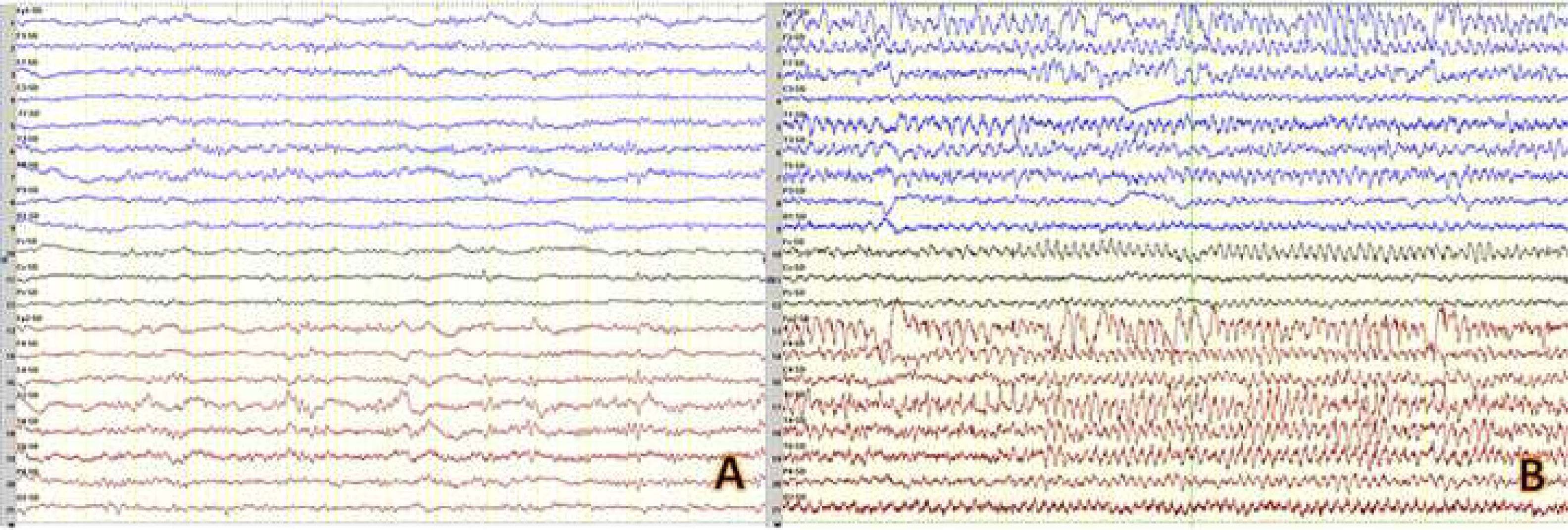

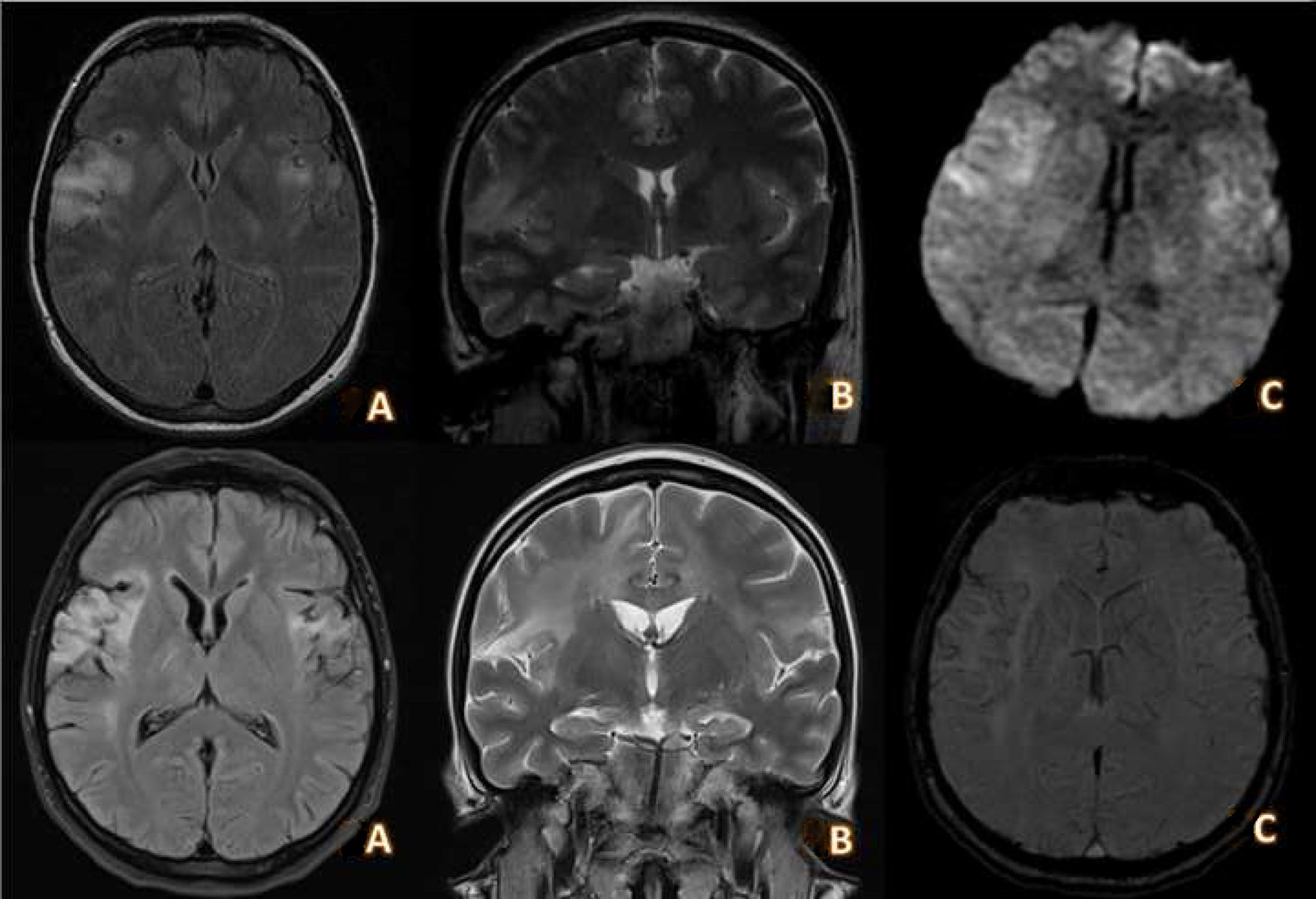

A complete blood analysis, including serology tests for HIV and a lymphocyte population study, yielded normal results. Serial electroencephalography (EEG) studies showed epileptiform activity in right temporal regions, together with signs of focal slowing. During a video EEG study, the patient presented a generalised tonic-clonic seizure with a generalised spike-and-wave pattern preceded by right temporal recruiting rhythm (Fig. 1). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed T2-FLAIR hyperintensities without contrast uptake in both insular cortices, superior temporal gyri, cingulate, and pre- and postcentral gyri (Fig. 2). A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a high protein level (0.81 g/dL), with 121 cells (94% lymphocytes); a PCR test for HSV-2 yielded positive results. Results were negative in the other microbiological studies, including the PCR tests for the remaining viruses of the herpes, cytomegalovirus, human parechovirus, and enterovirus families; PCR test and antigen detection for Cryptococcus; Gram staining and bacterial cultures; and PCR test for Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Listeria monocytogenes; as well as testing for anti-NMDA receptor antibodies.

Video EEG. A) Interictal EEG showing right frontotemporal focal abnormalities consisting of periodic complex waves with a frequency below 1 Hz and variable propagation to other areas. B) Ictal EEG recording showing a generalised spike-and-wave pattern that was preceded by recruiting rhythms in the right temporal region, with fast propagation.

Brain MRI study performed during the acute phase (top) and at 20 days after completion of antiviral treatment (bottom). Top, A and B) Axial and coronal slices from a T2-FLAIR sequence showing hyperintense lesions extending through the insular cortex and superior temporal gyri towards the pre- and postcentral gyri and predominantly right cingulate gyrus. C) DWI sequence showing moderately restricted diffusion in the lesions described. Bottom, A and B) Axial and coronal slices from a T2-FLAIR sequence showing areas of gliosis with cystic necrosis in the insular, opercular, and bilateral frontotemporal regions, predominantly affecting the right side. C) DWI sequence showing haemosiderin deposition predominantly in the right insular area, compatible with superficial siderosis secondary to encephalitis.

We started treatment with intravenous aciclovir for 21 days and antiepileptic treatment with lacosamide; a follow-up CSF analysis returned negative PCR results for HSV-2. A follow-up brain MRI performed at 20 days showed cystic necrosis in bilateral frontal regions (Fig. 2).

The patient showed improvements in facial mobility and was able to perform voluntary movements with the face, mouth, and tongue; however, due to persistent dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia, she required nutrition via nasogastric tube for 3 months, which was subsequently removed. No further epileptic seizures were observed.

Herpesvirus encephalitis is the most frequent cause of sporadic encephalitis worldwide, with HSV-1 infection being more frequent in adults and HSV-2 in newborns.5 HSV-2 encephalitis in adults is exceptional, and has been described in association with ischaemic and/or haemorrhagic stroke,6 or with symptoms similar to those of HSV-1 encephalitis.5

The most frequent cause of FCMS in adults is vascular lesions due to simultaneous or sequential involvement of both opercular cortices or their subcortical connections.2,3 It has rarely been associated with a unilateral opercular lesion.7 HSV-1 encephalitis is an important infectious cause of FCMS,8,9 due to its high prevalence and the predominant involvement of the frontal lobes.5 The most typical presentation consists of encephalitis with fever, impaired level of consciousness, and epileptic seizures (mainly focal motor seizures) whose clinical symptoms include signs of opercular syndrome; however, cases have also been reported of FCMS in isolation or associated with focal motor seizures only.10 In these cases, the appearance of recurrent focal seizures, even in the absence of fever, headache, or other data suggesting meningoencephalitis, should move us to rule out infection of the central nervous system, especially in patients presenting no vascular risk factors. Other microbial causes (cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, toxoplasma, tuberculosis, or JC virus) are extremely rare.11–14

Other causes described include head trauma, demyelinating lesions, brain tumours, neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, neurodegenerative diseases, and status epilepticus.1,15

Our patient’s symptoms initially consisted of focal seizures, with no language impairment or altered level of consciousness between seizures, and without headache, fever, or increased levels of acute-phase reactants. She subsequently developed anarthria, dysphagia, and bilateral facial paresis with preserved automatic and emotional responses (smiling, crying, yawning), which is typical of bilateral anterior opercular involvement. This automatic-voluntary dissociation is explained by preservation of the indirect corticobulbar pathway.1

In short, HSV-2 encephalitis can cause FCMS in immunocompetent adults; this has not previously been described in the literature.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Gascón D, Sancho-Saldaña A, Carilla Sanromán A, Bertol Alegre V. Síndrome de Foix-Chavany-Marie secundario a encefalitis por virus herpes simple tipo 2. Neurología. 2021;36:483–486.