Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is a chronic, painful skin disorder affecting the distal segment of the lower limbs. From a histopathological viewpoint, it is characterised by thrombosis of the dermal arteries, with no leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Patients typically present purple-coloured macules, which may progress to ulcers and leave white scars after healing (atrophie blanche).1,2 In some cases, LV has been associated with mononeuritis multiplex (MM) secondary to thrombosis of the vasa nervorum. We present the first reported case of vasculitic MM associated with LV.

Our patient was a 58-year-old man with no relevant medical history, who presented 2 months’ progression of pain and progressive loss of strength and sensitivity in both feet, associated with erythematous lesions on the tops of the feet. He also reported loss of sensitivity in the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand. He presented no constitutional symptoms and had no history of systemic disease.

The examination detected confluent erythematous macules in both feet, compatible with livedo racemosa, and no ulcers or atrophie blanche. Muscle strength was 3/5 in plantar flexion and 2/5 in dorsiflexion. Patellar and Achilles reflexes were absent in the left limb and hypoactive in the right. The patient also displayed reduced tactile and pain sensitivity below the knees and in the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand. The remaining results of the neurological examination were normal.

Laboratory analyses yielded normal results, including normal levels of homocysteine, cryoglobulins, lupus anticoagulant, and rheumatoid factor. Tests for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-®2 microglobulin, anticardiolipin, antiganglioside, and antineuronal antibodies returned negative results; results from serology tests for syphilis, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV were also negative. CSF analysis yielded normal results, with no oligoclonal bands. Screening tests for hereditary thrombophilia and occult cancer yielded negative results.

A neurophysiological study detected increased distal latencies and low-amplitude motor evoked potentials in the peroneal and tibial nerves. Somatosensory evoked potentials were not detected in the sural nerves. Low-amplitude motor evoked potentials were detected in the right ulnar nerve. Electrical activity was normal in both median nerves and the left ulnar nerve.

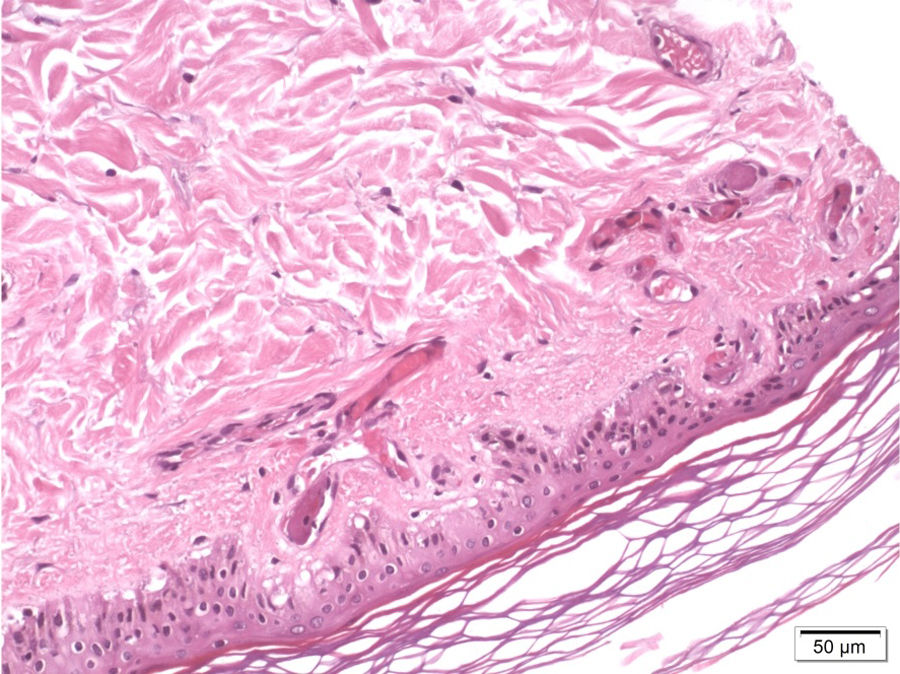

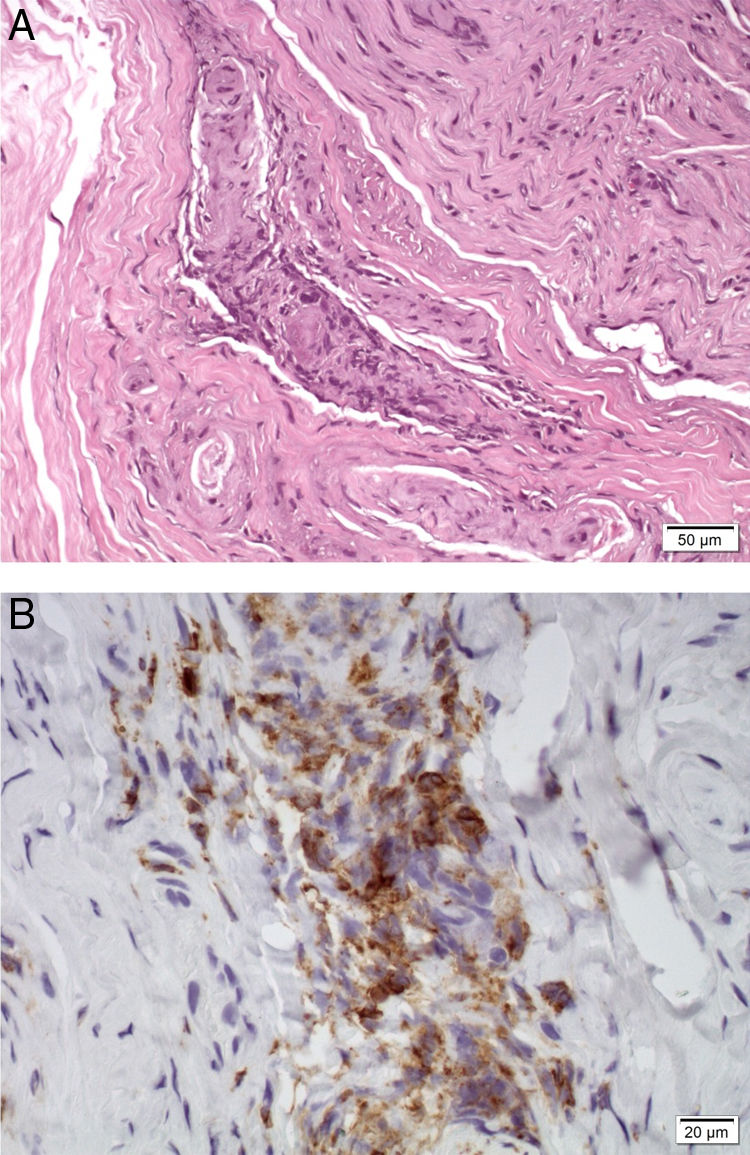

A skin biopsy revealed occlusive vasculopathy in the superficial and deep dermal arteries, with areas of mural hyalinisation, no inflammatory infiltrate, and preserved epidermis; these findings are consistent with LV (Fig. 1). A sural nerve biopsy revealed intense loss of myelinated fibres. An epineurial artery showed CD45+ inflammatory infiltrate, with arterial wall infiltration and destruction (Fig. 2). No thrombosis was observed in other arteries.

The patient was treated with acetylsalicylic acid at 100 mg/day, prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day, and amitriptyline and tramadol as rescue medications; treatment relieved pain and strength and sensitivity progressively improved. Skin lesions improved progressively, leaving no atrophie blanche. A year after the first consultation, the patient presented deep vein thrombosis in the right leg, which was attributed to immobilisation and treated with acenocoumarol for 6 months. Again, tests for thrombophilia and occult cancer yielded negative results. The dose of prednisone was gradually reduced, and the drug was suspended at 19 months. The patient remains asymptomatic after 6 years of follow-up.

LV was diagnosed based on the characteristic skin biopsy findings.1 The condition is not always associated with atrophie blanche.1,2 The pathogenesis of LV is unclear. In many cases, the condition is associated with acquired or hereditary thrombophilia, neoplasia, or systemic diseases.1,2 However, it may also appear in isolation, as in our patient; in this case, coagulopathy and systemic disease could not be confirmed, despite extensive testing and a long follow-up period.

The literature includes cases of peripheral neuropathy as an extracutaneous manifestation of LV, usually with a clinical and electrophysiological pattern of mononeuritis multiplex.3–9 In a retrospective series of 70 patients with LV, 9% presented peripheral neuropathy.10 In some patients, biopsy studies reveal ischaemic neuropathy secondary to thrombosis of the vasa nervorum, with no signs of vasculitis.4,6,7,9 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of vasculitic MM associated with LV. We should consider this diagnostic possibility and perform a nerve biopsy in these patients, as immunosuppressive treatment may resolve the symptoms.

Our patient met the diagnostic criteria for non-systemic vasculitic neuropathy (NSVN), as the nerve biopsy revealed inflammatory infiltrate in the vessel wall and signs of vascular damage, with no evidence of systemic vasculitis.11 Copresence of NSVN and LV, and the simultaneous improvement of both conditions after initiation of corticosteroid treatment, suggest a pathogenic association between the 2, although the nature of this association is unclear. LV may be associated with other inflammatory diseases, such as connective tissue disorders, and may therefore be associated with NSVN.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Please cite this article as: Corral Í, Kawiorski MM, Moreno C, Pian H. Mononeuritis múltiple vasculítica asociada a vasculopatía livedoide. Neurología. 2020;35:616–617.