Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the gene that encodes α-tocopherol transfer protein (TTPA), located on chromosome 8q12.3.1 These mutations cause low vitamin E levels due to impaired hepatic transport of the vitamin despite adequate intestinal absorption.2 The condition is characterised by a cerebellar syndrome with ataxia, extensor plantar reflex, areflexia, and sensory deficits, resembling Friedreich ataxia.3,4 However, it may present with other neurological (dystonia, tremor, myoclonus) and non-neurological symptoms (retinitis pigmentosa, xanthelasma, tendon xanthomas, or cardiac alterations).5

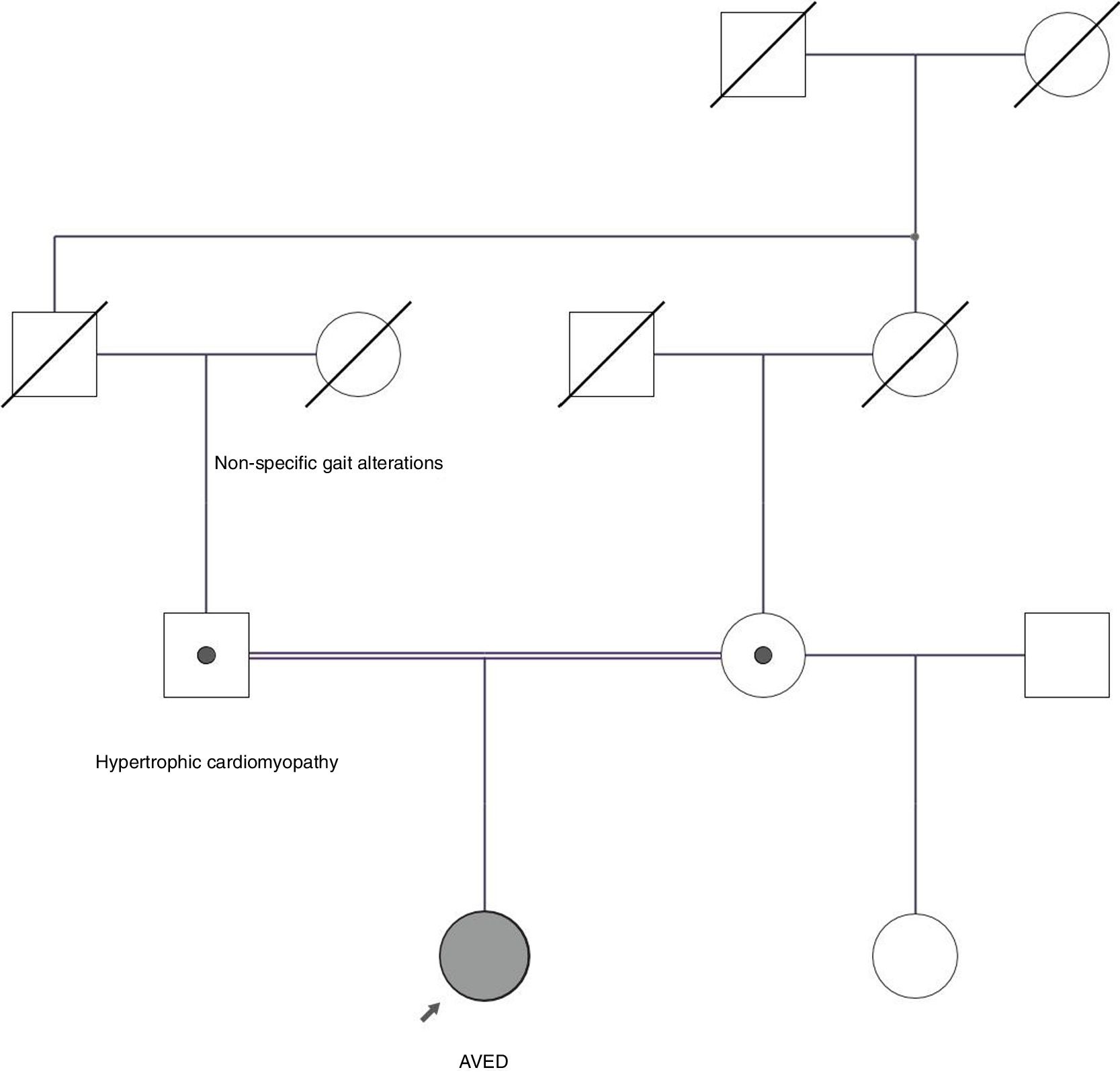

We present the case of a 27-year-old woman who had presented difficulty speaking and walking since the age of 8 years. At a later age she developed cerebellar ataxia with falls. Her paternal grandmother presented gait alterations, and her parents were consanguineous (Fig. 1). Her father presented hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

Pedigree chart of our patient's family. Her parents are consanguineous (first cousins) and both carry a heterozygous pathogenic mutation. The father had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The paternal grandmother presented non-specific gait alterations. No genetic data are available from deceased relatives.

General examination of the patient revealed kyphoscoliosis and pes cavus. The neurological examination revealed scanning speech and transient gaze-evoked nystagmus at bilateral extreme gaze positions, associated with a mild increase in saccadic latency. The patient also presented generalised hypotonia, bilateral dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, truncal ataxia with positive Romberg sign, gait instability, wide-based gait with irregular walking cadence, difficulty in tandem walking, generalised areflexia, bilateral Babinski sign, and reduced vibration sensitivity in both legs. A brain MRI scan revealed platybasia. Electromyography detected marked alterations in the dorsal column and pyramidal tracts for both the upper and the lower limbs. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed no alterations.

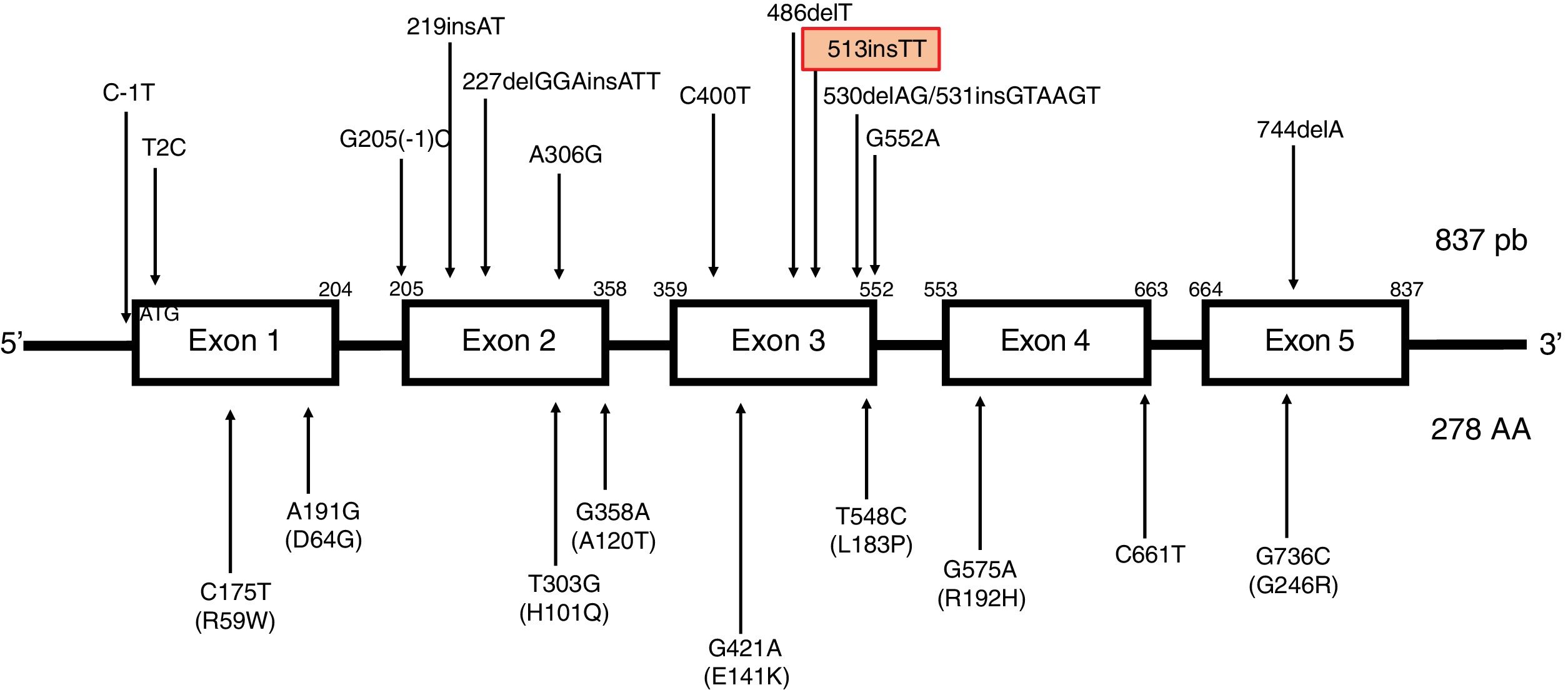

Our first diagnostic hypothesis was Friedreich ataxia, given the symptoms of progressive ataxia with areflexia and presence of bilateral Babinski sign, although a study of the frataxin gene detected no abnormalities. A biochemical analysis confirmed vitamin E deficiency, with an α-tocopherol concentration of 4.72μmol/L (normal range, 18.6–46.2μmol/L). The remaining laboratory parameters yielded normal values. Diagnosis of AVED was confirmed by TTPA gene sequencing: the patient was found to be a homozygous carrier of the pathogenic variant c.513_514insTT. α-Tocopherol levels were normal in the patient's mother and low in her father (11.61μmol/L). Both parents were heterozygous carriers of the c.513_514insTT mutation.6–8 Genetic testing for cardiomyopathy revealed that the father was a heterozygous carrier of MYH6 mutation c.4288T>G. This gene encodes the α heavy chain subunit of cardiac myosin, which is mainly expressed during the development. Mutations in MYH6 have been linked to a wide range of heart diseases, including different types of dilated/hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,9 such as familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 14 (OMIM #613251). The c.4288T>G mutation results in the replacement of leucine with valine at position 1430. According to a bioinformatic study, this is a variant of uncertain significance.

Our patient started treatment with parenteral vitamin E dosed at 800mg/day; however, plasma vitamin E levels remained low and the dose had to be doubled. The patient has remained clinically stable since then.

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble antioxidant molecule that suppresses the release of reactive oxygen species, conferring it protective effects against diseases associated with oxidative stress, including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and neoplastic diseases.10 Vitamin E deficiency causes neurological alterations associated with oxidative stress, leading to neuronal loss and demyelination. It also causes deposition of lipid peroxidation derivatives and lipofuscin aggregation, resulting in impaired axonal transport.11,12 Post mortem studies have found a correlation between ataxia and cerebellar Purkinje cell loss.13

The most frequent mutations are the c.744delA (associated with a founder effect in North African populations) and c.513insTT frameshift mutations. The latter mutation results in the insertion of 2 thymine residues at position 513, causing a shift in the reading frame that results in a premature stop codon. It has been detected in patients from Northern Europe, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Italy,4 mainly in association with cerebellar symptoms (Fig. 2).

Description of the TTPA gene. Located on chromosome 8, the gene is composed of 5 uniformly spliced exons with an open reading frame of 834 base pairs, and encodes a cytosolic protein containing 278 amino acids. TTPA is the only gene to be associated with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency to date. No single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been identified in the protein-coding region of TTPA. The types of variants that cause diseases associated with the TTPA gene are missense mutations; nonsense mutations; splicing site mutations; and small deletions, insertions, and indels. Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency shows nearly complete penetrance in homozygous or compound heterozygous carriers of TTPA mutations. Mutations have been reported in all exons of the gene. The most frequent mutations are 744delA, in exon 5 (predominantly in North African populations), and 513insTT, in exon 3 (more frequent in Northern Europe).

According to some case series, prevalence of cardiomyopathy ranges from 19% to 31%,4,14,15 presenting as left ventricular hypertrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, or electrocardiographic alterations. Furthermore, cases have been reported of patients with AVED and early-onset systemic disorders (atherosclerotic vascular disease, ischaemic heart disease, fatty liver) in the absence of relevant risk factors; this may be explained by the protective effects of α-tocopherol for myocardial function due to its ability to reduce oxidative stress.15,16

However, heart disease had not previously been described in a heterozygous carrier. We may hypothesise that sustained low α-tocopherol levels may be linked to heart disease, since affected individuals (patients with homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations) and heterozygous individuals with low α-tocopherol levels share the main metabolic factor leading to the cardiomyopathy observed in AVED. Furthermore, our patient's mother was also a heterozygous carrier of the same mutation, but showed normal α-tocopherol levels and presented no neurological or cardiac symptoms. This suggests that the genotype-phenotype relationship may involve factors other than low α-tocopherol levels. Furthermore, heterozygous presence of multiple recessive mutations may increase an individual's susceptibility to develop phenotypic traits of the disease. In the case presented here, α-tocopherol deficiency may have favoured the phenotypic expression of the heterozygous mutation in MYH6.

The importance of suspecting this entity lies in the possibility of early diagnosis, which enables early introduction of vitamin E supplementation to prevent the development of disabling signs and symptoms.17 Patients and mutation carriers should undergo cardiology studies.

FundingThis study received no public or private funding.

Please cite this article as: Lucas-Del-Pozo S, Moreno-Martínez D, Tejero-Ambrosio M, Hernández-Vara J. Ataxia por déficit de vitamina E en una familia con posible afectación cardíaca. Neurología. 2021;36:92–94.