Survival rates among patients with cancer have increased in recent years. However, the prognosis of lung cancer continues to be poor, especially at advanced stages of the disease1; brain metastases require radiation therapy in most cases.2 This has led to an increase in the incidence of late adverse effects of brain radiation, such as leukoencephalopathy and radiation necrosis.3 Since the first case of stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome was described by Shuper et al.4 in 1995, nearly one hundred cases have been reported worldwide.5 Although SMART syndrome is extremely rare, improvements in cancer survival rates are very likely to result in an increase in the frequency of this entity. We describe the case of a patient who presented SMART syndrome.

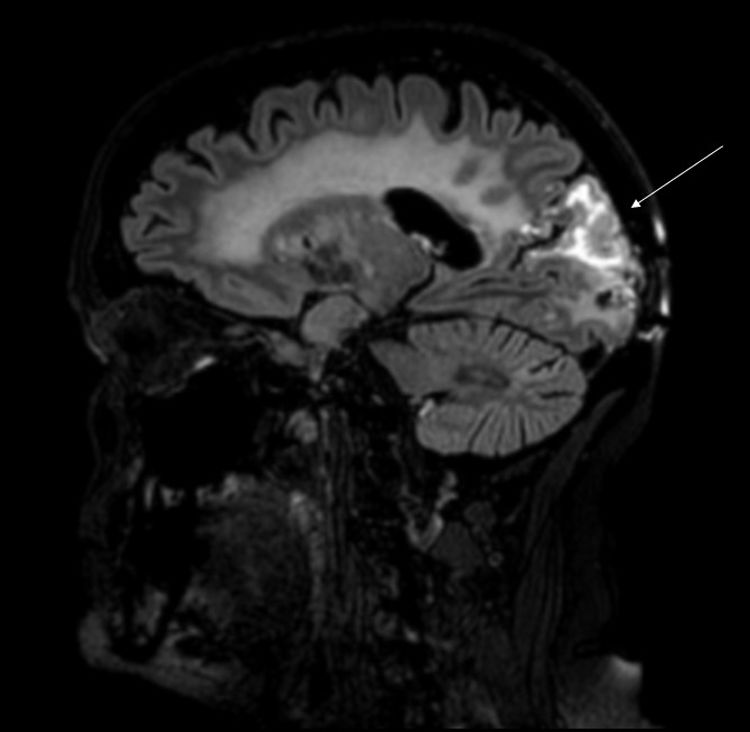

Our patient was a 62-year-old woman, a smoker of 40packs/year, with history of stage IIA papillary adenocarcinoma of the lung (pT2bN0M0) diagnosed in 2013. She underwent pulmonary lobectomy and received chemotherapy (4 sessions of cisplatin and docetaxel). She presented tumour progression in 2015, and 3 brain metastases were detected. She underwent surgical removal of the right occipital lesion and received whole-brain radiation therapy (30Gy over 10 sessions). Three years later, she consulted due to visual alterations and weekly episodes of 4-12 hours’ duration of holocranial pulsating headache of 7-8/10 intensity on the verbal analogue scale, associated with photophobia (but not phonophobia or osmophobia), clinophilia, and increased sensitivity to mechanical stimulation. The patient reported painless vision loss and progressive, sustained weakness of the left arm and leg. The physical examination revealed no fever, normal blood pressure, left homonymous hemianopsia, visual agnosia, and hemiparesis affecting the left arm and leg. A complete blood count, biochemical analysis, and autoimmunity study all yielded normal results. An electroencephalography revealed no abnormalities. A brain MRI scan revealed postsurgical changes in the right occipital pole and above this location, involving the right parietal and occipital lobes. The affected region displayed cortical thickening and hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences, associated with subcortical oedema and marked gyral enhancement (Fig. 1). Treatment with intravenous dexamethasone (4mg/6h) improved visual and motor symptoms.

The pathophysiology of SMART syndrome is poorly understood. In all the cases reported, patients had previously received brain radiation therapy. Although the syndrome was initially associated with high doses (>50Gy), cases have also been reported in patients receiving lower doses6,7; all cases occurred after doses ranging from 15 to 64Gy.8 Neurotoxicity disrupts the blood-brain barrier, damages endothelial cells, and causes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and vascular fibrinoid necrosis, ultimately leading to vascular occlusion. This explains why the pathogenesis of SMART syndrome was attributed to these factors. However, in the series published by Black et al.,9 brain biopsy studies did not identify vascular alterations, but rather nonspecific gliosis. Proposed causes of SMART syndrome include disruption of the trigeminovascular system and radiation-induced neuronal dysfunction, which suggests that the syndrome may bear a greater resemblance to migraine or epilepsy than to cerebrovascular disease.7

Mean time from brain radiation therapy to diagnosis of SMART syndrome was 10 years (range, 1-35).5

SMART syndrome is characterised by subacute onset of neurological symptoms (aphasia, hemianopsia or complete vision loss, hemiparesis, hemiparaesthesia, hearing loss), seizures, migraine-like headache, and encephalopathy of varying severity, ranging from mild psychomotor retardation to severely impaired consciousness.10 In the largest series published to date,5 the most frequent symptoms were neurological deficits and headache. SMART syndrome completely resolved in most cases, but some patients were left with sequelae or even experienced relapses. The course of the syndrome seems to be relapsing-remitting.

MRI typically shows unilateral cortical hyperintensities on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, with gyriform enhancement, predominantly in the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Diagnosis of SMART syndrome is clinical and radiological and must be based on a compatible medical history. In 2015, Zheng et al.10 reviewed the criteria established by Black et al.11 and proposed a new set of diagnostic criteria (Table 1). Alternative diagnoses include brain radiation necrosis. Although brain radiation necrosis may occur at any time, it has been reported to present at 10 to 16 months post-treatment in several series.11–15 Although no pathognomonic radiological signs of brain radiation necrosis have been described, MRI typically reveals necrotic lesions, usually with surrounding oedema and mass effect. These findings are described as having a “Swiss cheese” or “soap bubble” appearance.13,16,17 No targeted treatment is available; management of these patients focuses on symptom control. While corticosteroids may improve neurological deficits, their use continues to be controversial.7,11,18–21

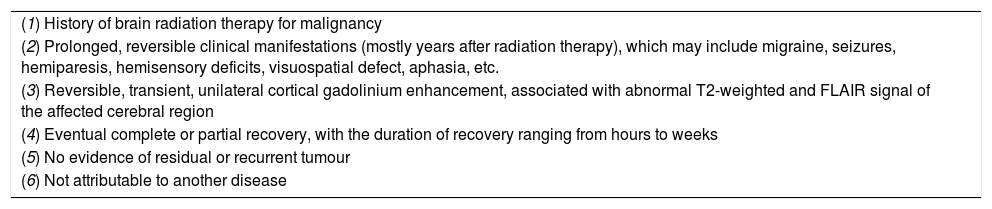

Diagnostic criteria for stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy syndrome.

| (1) History of brain radiation therapy for malignancy |

| (2) Prolonged, reversible clinical manifestations (mostly years after radiation therapy), which may include migraine, seizures, hemiparesis, hemisensory deficits, visuospatial defect, aphasia, etc. |

| (3) Reversible, transient, unilateral cortical gadolinium enhancement, associated with abnormal T2-weighted and FLAIR signal of the affected cerebral region |

| (4) Eventual complete or partial recovery, with the duration of recovery ranging from hours to weeks |

| (5) No evidence of residual or recurrent tumour |

| (6) Not attributable to another disease |

SMART syndrome should be considered in all patients with history of radiation therapy who present neurological deficits and parieto-occipital MRI alterations.

Please cite this article as: Martín Guerra JM, López Castro R, Martín Asenjo M, García Azorin D. Síndrome de SMART. Neurología. 2021;36:90–92.