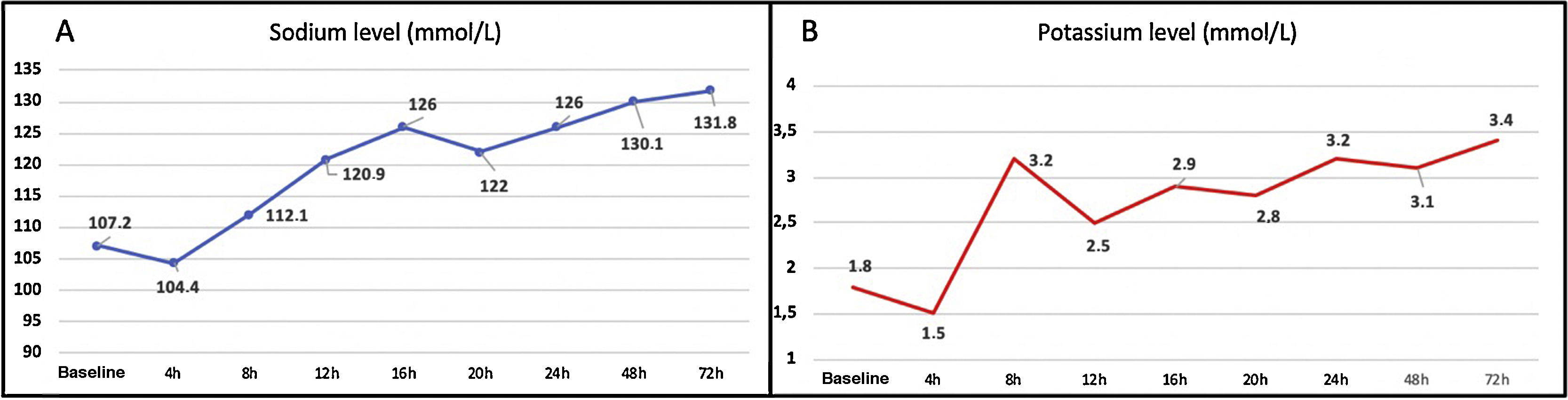

Osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS) is a rare, severe neurological complication of some metabolic disorders. Although rapid correction of severe hyponatraemia (< 120 mmol/L) is the most frequent trigger factor (occurring in nearly 50% of cases1–3), other concomitant factors have also been described, including alcohol abuse or withdrawal, hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, and bulimia nervosa.3–6 ODS mainly presents between days 1 and 14 after onset of hyponatraemia treatment, and its clinical manifestations vary considerably. The syndrome initially presents with encephalopathy, which subsequently improves and is followed by dysarthria, dysphagia, oculomotor alterations, and quadriparesis, and may progress to locked-in syndrome.1,2 We present the case of a 30-year-old woman who was attended at our hospital’s emergency department after collapsing due to loss of consciousness. She had history of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine use; an eating disorder (probably bulimia); and chronic, compulsive use of diuretics to lose weight. During the initial assessment, the patient showed fluctuations in alertness, with alternating episodes of agitation and decreased level of consciousness. A thorough study, including blood analysis, electrocardiography, and head CT, revealed severe hypoosmolar hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia (Na 107 mmol/L; K 1.8 mmol/L; osmolality 215 mOsm/kg), significant prolonged QT interval (660 ms), and epidural haematoma; the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Intravenous administration of hypertonic saline solution increased blood sodium concentration by 17 mmol/L in less than 24 hours (Fig. 1A and B). A week after symptom onset, the patient was discharged with no neurological symptoms or any other alterations (Na 138 mmol/L and K 3.8 mmol/L at discharge).

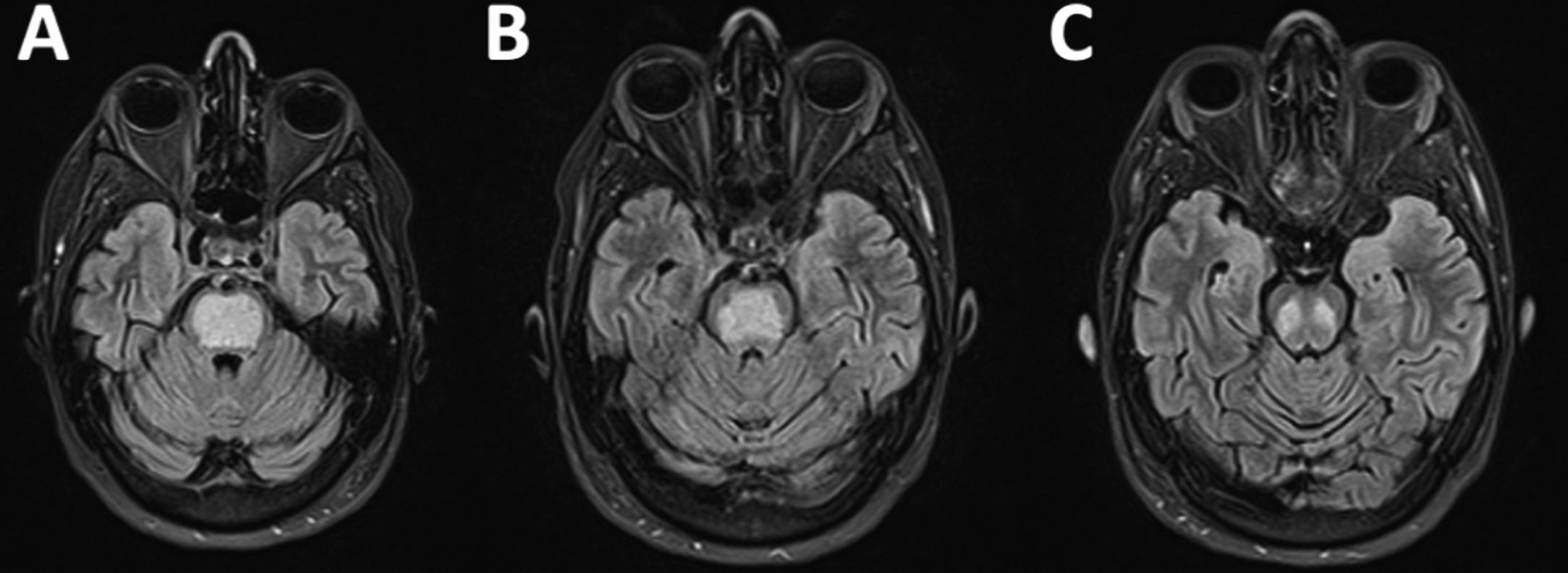

Eleven days after discharge (21 days after the episode of loss of consciousness), the patient visited the emergency department due to right limb weakness, which had progressively worsened over the previous 48 hours. The neurological examination revealed mixed consistency dysphagia, dysarthria, and absent gag reflex bilaterally, with severe right-sided faciobrachiocrural paralysis, mild left-sided crural paresis, and bilateral pyramidal signs. Blood electrolyte levels were normal. She was admitted to the neurology department for assessment. A brain MRI scan revealed a well-delimited area occupying the central part of the pons, which was hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences (Fig. 2A-C). This finding is highly suggestive of pontine osmotic demyelination. The patient started intensive physical therapy during hospitalisation, and continued with the treatment on an outpatient basis. At 3 months of follow-up, she was able to walk unaided, although mild ataxia persisted.

Although the pathophysiological mechanism of ODS is not well understood, hyponatraemia is known to cause a loss of osmotically active substances in astrocytes; when ion imbalances are corrected, if tonicity increases faster than osmole synthesis, mobilisation of water from the intracellular to the extracellular space results in decreased cerebral volume.7–14

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of late-onset ODS (occurring more than 14 days after the precipitating event). We hypothesise that, in addition to the electrolyte imbalances described, presence of multiple risk factors for ODS (consumption of alcohol and other drugs, bulimia, and excessive diuretic use possibly leading to chronic dyselectrolytaemia11–14) may have had a protective effect, since the patient may have experienced fluctuations in electrolyte levels. Although no data were available on our patient’s sodium levels prior to the initial consultation, hyponatraemia may have been chronic, delaying the effects of acute osmotic lesions to the pons. Another hypothesis is that the patient underestimated the initial symptoms or that osmotic demyelination progressed slowly, beginning days before symptom onset (however, upon questioning, the patient reported no previous symptoms).

Our case is interesting in that it shows that the temporal window for late-onset ODS is wider than previously thought. The condition should therefore be included in the differential diagnosis of acute neurological deficits of unknown aetiology.

Please cite this article as: Puig I, Alvarez M, Lozano M, Lucente G. Un caso de síndrome de desmielinización osmótica de inicio tardío. Neurología. 2021;36:640–641.