Recent analyses emphasise that The Benchmark Stroke Door-to-Needle Time (DNT) should be 30min. This study aimed to determine if a new in-hospital IVT protocol is effective in reducing door-to-needle time and correcting previously identified factors associated with delays.

Material and methodsIn 2014, we gradually introduced a series of measures aimed to reduce door-to-needle time for patients receiving IVT, and compared it before (2009-2012) and after (2014-2017) the new protocol was introduced.

ResultsThe sample included 239 patients before and 222 after the introduction of the protocol. Median overall door-to-needle time was 27min after the protocol was fully implemented (a 48% reduction on previous door-to-needle time [52min], P<.001)]. Median door-to-needle time was lower when pre-hospital code stroke was activated (22min). We observed a 26-min reduction in the median time from onset to treatment (P<.001). After the protocol was implemented, the “3-hour-effect” did not affect door-to-needle time (P=.98). Computed tomography angiography studies performed before IVT were associated with increased door-to-needle time (P<.001); however, the test was performed after IVT was started in most cases.

ConclusionsHospital reorganisation and multidisciplinary collaboration brought median door-to-needle time below 30min and corrected previously identified delay factors. Furthermore, overall time from onset to treatment was also reduced and more stroke patients were treated within 90min of symptom onset.

El objetivo del tiempo puerta-aguja en el ictus isquémico agudo tratado con trombólisis intravenosa (TIV) tiende a situarse actualmente en los 30min. Determinamos si un nuevo protocolo de actuación intrahospitalario es eficaz para reducir el intervalo puerta-aguja y corregir los factores de demora previamente identificados.

Material y métodosEn 2014 se implantaron gradualmente unas medidas diseñadas para acortar los tiempos de actuación intrahospitalarios en los pacientes tratados con TIV. Se compararon los tiempos de actuación antes (2009-2012) y después (febrero 2014-abril 2017) de la introducción del nuevo protocolo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 239 pacientes antes y 222 después. Cuando todas las medidas fueron introducidas, la mediana global de tiempo puerta-aguja fue de 27min (previa 52min, 48% menos, p<0,001) y de 22min cuando se activó el código ictus extrahospitalario. El tiempo global al tratamiento (inicio-aguja) se redujo en 26min de mediana (p<0,001). En el período postintervención ya no se objetivó el «efecto de fin de ventana» (p=0,98). Aunque la angio-TC antes de la TIV continuó retrasando los tiempos de actuación (p<0,001), tras el nuevo protocolo, esta prueba se realizó después del inicio del tratamiento en la mayoría de los casos.

ConclusionesLa reorganización intrahospitalaria y la colaboración multidisciplinar han situado la mediana de tiempo puerta-aguja por debajo de los 30min y han corregido los factores de demora identificados previamente. Además, se ha reducido el tiempo global al tratamiento y una mayor proporción de pacientes son tratados en los primeros 90min desde el inicio de los síntomas.

According to the most recent meta-analyses of intravenous (IV) thrombolytic treatment for acute ischaemic stroke, time to treatment continues to be the most important prognostic factor, even before age or stroke severity.1,2 Although IV thrombolysis continues to be the first treatment option for acute ischaemic stroke,3 combined treatment with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) and mechanical thrombectomy has recently been shown to be superior.4–6

Given the enormous significance of time in the functional prognosis of stroke patients, proper management of time between symptom onset and treatment is essential.7,8

In recent years, “ultra-rapid” action protocols have reduced door-to-needle times (time elapsed between the patient's arrival at hospital and administration of IV thrombolysis) to a median of 20minutes.9–11 This door-to-needle time is much shorter than the 60-minute period initially recommended by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines, and even the 45-minute period recommended in its latest update.12

However, no comparable in-hospital protocols have been developed in our setting. A recent multi-centre study prospectively analysing door-to-needle times in 8 Spanish stroke units in 2013 reports a median door-to-needle time of 64minutes.13 A 2015 analysis of stroke units in the Spanish region of Madrid revealed a median door-to-needle time of 54minutes.14 A retrospective study conducted in our centre's stroke unit analysed patients treated between January 2009 and December 2012, finding a median door-to-needle time of 52minutes.15

Based on data from that study, the purpose of the present study was to analyse the impact of a new action protocol implemented to reduce door-to-needle times in a tertiary hospital in the region of Madrid, and to correct the factors associated with in-hospital delays in the previous study.

Material and methodsBackground and starting pointThe action protocol presented in this study was designed based on the retrospective analysis of patients receiving IV thrombolysis between 2009 and 2012.15 The study included 239 patients, and reported the following median (Q1-Q3) stroke management times (in minutes): onset-to-door time, 84 (60-120); door-to-CT time, 17 (13-24.75), CT-to-needle time, 34 (26-47); door-to-needle time, 52 (43-70); and onset-to-needle time, 145 (120-180). Furthermore, the multivariate regression analysis identified 2 factors associated with IV thrombolysis treatment delay: advanced neuroimaging studies (CT angiography) before treatment (13.5% increase in door-to-needle time), and the “3-hour effect” (door-to-needle time decreased by 4.7minutes for every 30minutes of onset-to-door time). In contrast, pre-hospital code stroke activation decreased door-to-needle time by 26.3%.

New action protocolThe new measures were introduced in February 2014 and gradually implemented until February 2017. The last measure, implemented in February 2017, was the administration of an rtPA bolus in the radiology room; this was available 7 days a week, between 08:00 and 22:00.

We prospectively gathered data from patients who received IV thrombolysis between February 2014 and April 2017 (3 months after the last measure was implemented). We compared stroke management times between the 2 series (before and after the implementation of the new protocol) and analysed whether the factors associated with in-hospital delays in the first sample had been corrected in the second. We excluded patients presenting in-hospital stroke and those transferred to our centre after undergoing diagnostic tests in another centre.

The impact of these measures on in-hospital times (door-to-CT, CT-to-needle, door-to-needle) has been addressed in a previous study.16

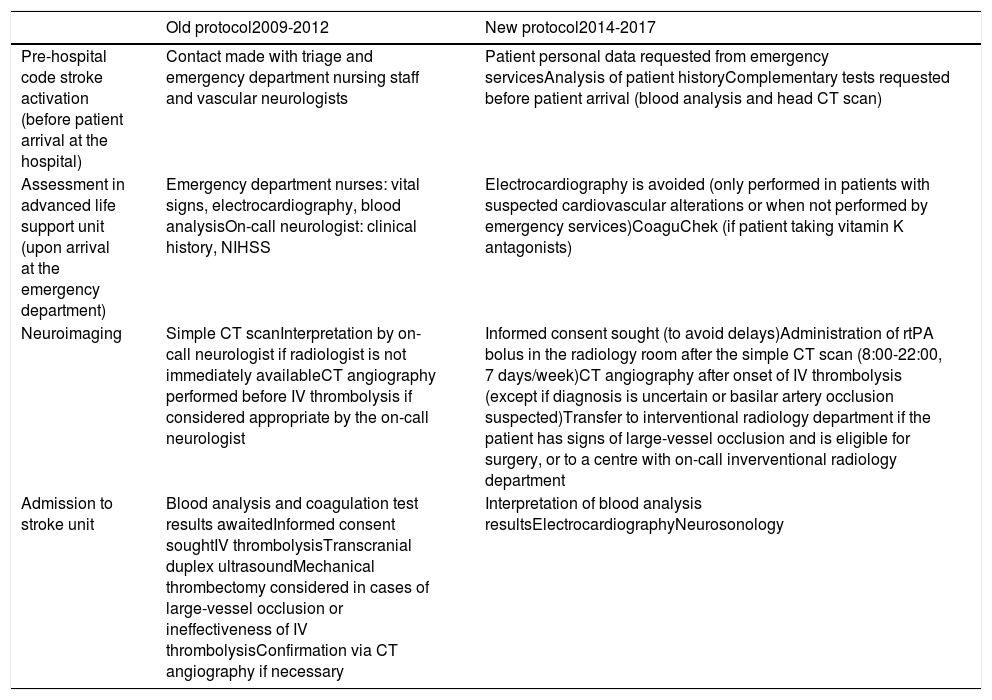

Table 1 summarises the changes introduced to the previous action protocol. In addition to these measures, feedback sessions were held once a month, with vascular neurologists, residents, on-call neurologists, and nurses sharing their ideas on potential issues and improvements with regard to the new protocol. We also named a “stroke team of the month” to acknowledge the consultant neurologist and the neurology resident achieving the shortest door-to-needle time.

In-hospital management of patients with acute ischaemic stroke before (2009-2012) and after (2014-2017) the implementation of the new protocol.

| Old protocol2009-2012 | New protocol2014-2017 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-hospital code stroke activation (before patient arrival at the hospital) | Contact made with triage and emergency department nursing staff and vascular neurologists | Patient personal data requested from emergency servicesAnalysis of patient historyComplementary tests requested before patient arrival (blood analysis and head CT scan) |

| Assessment in advanced life support unit (upon arrival at the emergency department) | Emergency department nurses: vital signs, electrocardiography, blood analysisOn-call neurologist: clinical history, NIHSS | Electrocardiography is avoided (only performed in patients with suspected cardiovascular alterations or when not performed by emergency services)CoaguChek (if patient taking vitamin K antagonists) |

| Neuroimaging | Simple CT scanInterpretation by on-call neurologist if radiologist is not immediately availableCT angiography performed before IV thrombolysis if considered appropriate by the on-call neurologist | Informed consent sought (to avoid delays)Administration of rtPA bolus in the radiology room after the simple CT scan (8:00-22:00, 7 days/week)CT angiography after onset of IV thrombolysis (except if diagnosis is uncertain or basilar artery occlusion suspected)Transfer to interventional radiology department if the patient has signs of large-vessel occlusion and is eligible for surgery, or to a centre with on-call inverventional radiology department |

| Admission to stroke unit | Blood analysis and coagulation test results awaitedInformed consent soughtIV thrombolysisTranscranial duplex ultrasoundMechanical thrombectomy considered in cases of large-vessel occlusion or ineffectiveness of IV thrombolysisConfirmation via CT angiography if necessary | Interpretation of blood analysis resultsElectrocardiographyNeurosonology |

In a sample of prospective patients receiving IV thrombolysis, we gathered data on demographic variables, stroke severity (NIHSS), stroke location (anterior/posterior territory), and whether code stroke was activated. We also gathered data on time from symptom onset to hospital arrival (onset-to-door time), time from hospital arrival to head CT scan (door-to-CT time), time from head CT scan to administration of IV thrombolysis (CT-to-needle time), and time from symptom onset to treatment with rtPA (onset-to-needle time). We determined the number of patients undergoing CT angiography before receiving IV thrombolysis, and stroke management times for each case.

The safety of the new protocol was evaluated according to the number of cases of symptomatic haemorrhagic transformation after treatment (ECASS-II criteria17) and the number of stroke mimics treated.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 20. Quantitative variables are expressed as medians and the first and third quartiles (Q1-Q3), and as means and standard deviation (SD). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare medians between 2 groups. We conducted a simple linear regression analysis to identify the variables affecting door-to-needle time. The factors showing significant results in the univariate analysis were included in the multiple linear regression model. Values of P≤.05 were considered statistically significant.

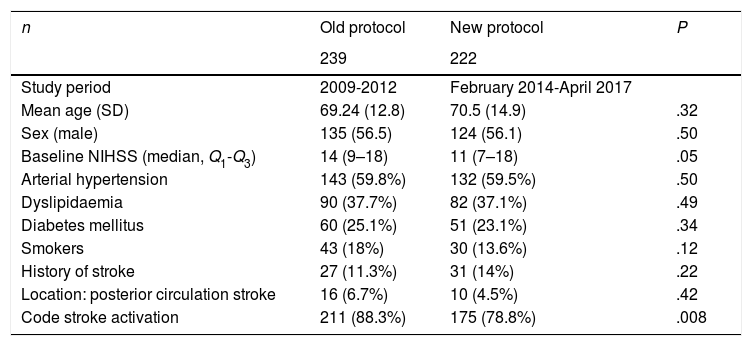

ResultsBaseline characteristicsA total of 222 patients received IV thrombolysis after the introduction of the new protocol. Fifty-nine of these were treated between February 2014 and December 2014, 69 patients were treated in 2015, 70 in 2016, and 24 in the first 4 months of 2017. Mean age (SD) was 70.5 (14.9) years; 56.1% of patients were men. The median (Q1-Q3) NIHSS score at baseline was 11 points (7-18). Code stroke was activated in 78.8% of cases. Table 2 summarises patient baseline characteristics before and after the implementation of the new protocol.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients treated with IV thrombolysis before and after implementation of the new protocol.

| n | Old protocol | New protocol | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 239 | 222 | ||

| Study period | 2009-2012 | February 2014-April 2017 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 69.24 (12.8) | 70.5 (14.9) | .32 |

| Sex (male) | 135 (56.5) | 124 (56.1) | .50 |

| Baseline NIHSS (median, Q1-Q3) | 14 (9–18) | 11 (7–18) | .05 |

| Arterial hypertension | 143 (59.8%) | 132 (59.5%) | .50 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 90 (37.7%) | 82 (37.1%) | .49 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 60 (25.1%) | 51 (23.1%) | .34 |

| Smokers | 43 (18%) | 30 (13.6%) | .12 |

| History of stroke | 27 (11.3%) | 31 (14%) | .22 |

| Location: posterior circulation stroke | 16 (6.7%) | 10 (4.5%) | .42 |

| Code stroke activation | 211 (88.3%) | 175 (78.8%) | .008 |

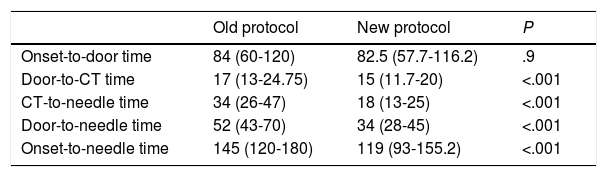

Median stroke management times (in minutes) after the new protocol was implemented were as follows: onset-to-door time, 82.5 (57.7-116.2); door-to-CT time, 15 (11.7-20); CT-to-needle time, 18 (13-25); door-to-needle time, 34 (28-45); and onset-to-needle time, 119 (93-155.2). All management times decreased significantly (P<.001), with the exception of onset-to-door time. Table 3 summarises stroke management times before and after the implementation of the new protocol.

In-hospital stroke management times (median, Q1-Q3) before (2009-2012) and after the implementation of the new protocol (February 2014-April 2017).

| Old protocol | New protocol | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset-to-door time | 84 (60-120) | 82.5 (57.7-116.2) | .9 |

| Door-to-CT time | 17 (13-24.75) | 15 (11.7-20) | <.001 |

| CT-to-needle time | 34 (26-47) | 18 (13-25) | <.001 |

| Door-to-needle time | 52 (43-70) | 34 (28-45) | <.001 |

| Onset-to-needle time | 145 (120-180) | 119 (93-155.2) | <.001 |

Considering the recommendations of the latest AHA/ASA guidelines,12 door-to-CT time was below 20minutes in 62.8% of patients before the implementation of the new protocol, compared to 78.8% of patients after it was implemented (P<.001). Door-to-needle time was below 45minutes in 21.6% and 68.2% of patients before and after the new protocol, respectively (P<.001), and below 30minutes in 5.4% and 37.4% of patients (P<.001).

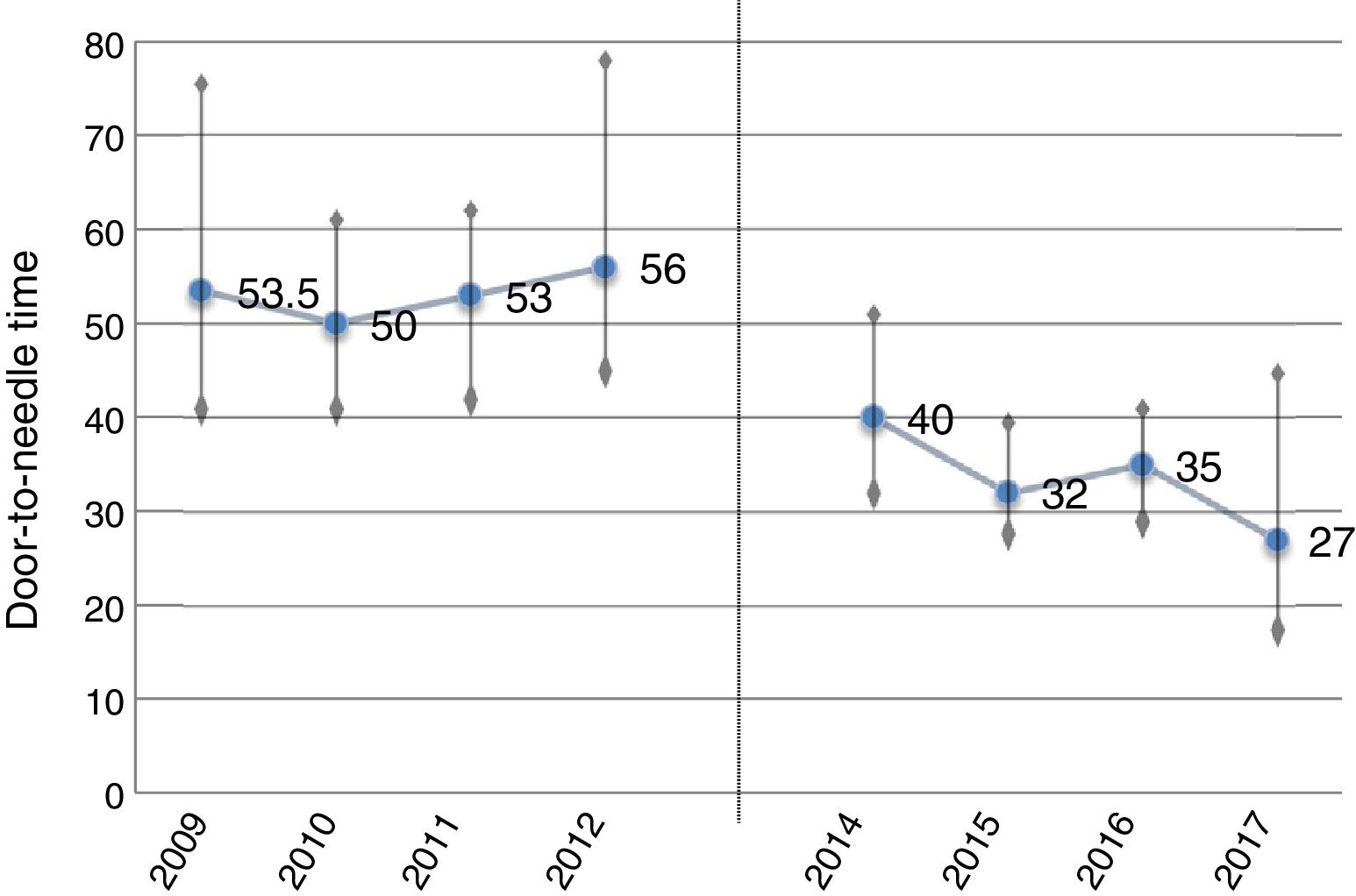

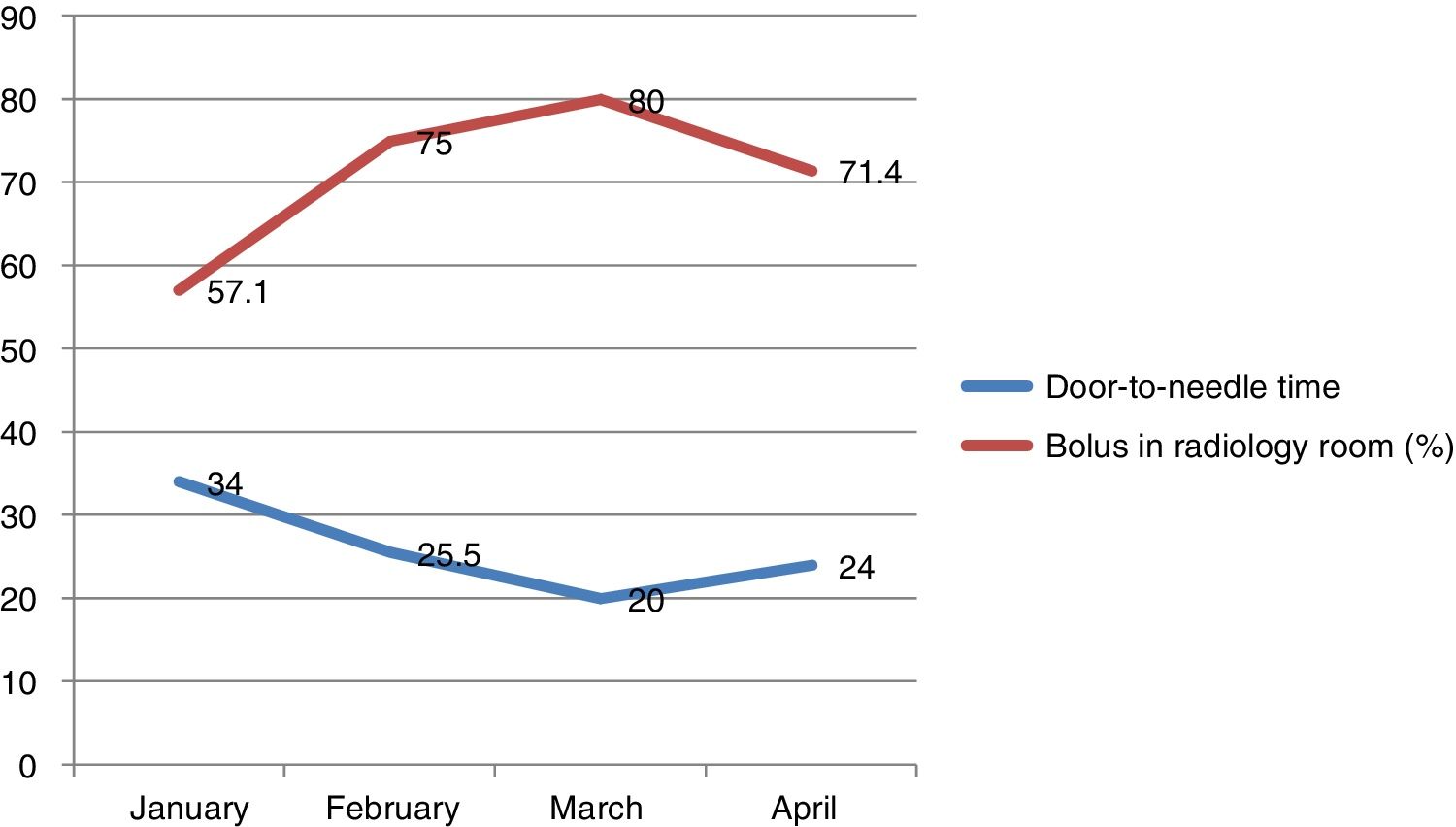

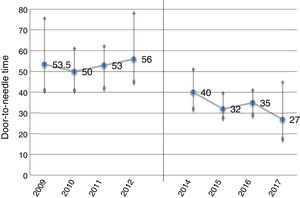

The median door-to-needle time during the first year of the new protocol was 40minutes, gradually decreasing to 27minutes in the last 4 months of the study; this coincided with the consolidation of treatment with rtPA bolus in the radiology room (a 48% decrease compared to the period before implementation of the new protocol; P<.001). Decreases were more marked in cases of pre-hospital code stroke activation, with a median of 22minutes in the last 4 months (Figs. 1 and 2).

Progression of door-to-needle times before (2009-2012) and after (2014-2017) the implementation of the new protocol. Over the last months of the study, with the new protocol fully implemented, door-to-needle time is < 30minutes (median in the last 4 months: 27minutes). In 2013, we analysed management times from the initial period and designed the new protocol.

In the last 3 months of the study period (when all protocol measures had come into force, including administration of rtPA in the radiology room and extension of the schedule for administration [8:00-22:00]), door-to-needle time was < 30minutes. Door-to-needle time decreased as the number of patients starting rtPA treatment in the radiology room increased.

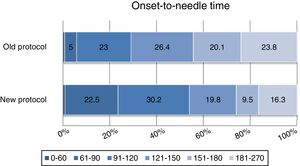

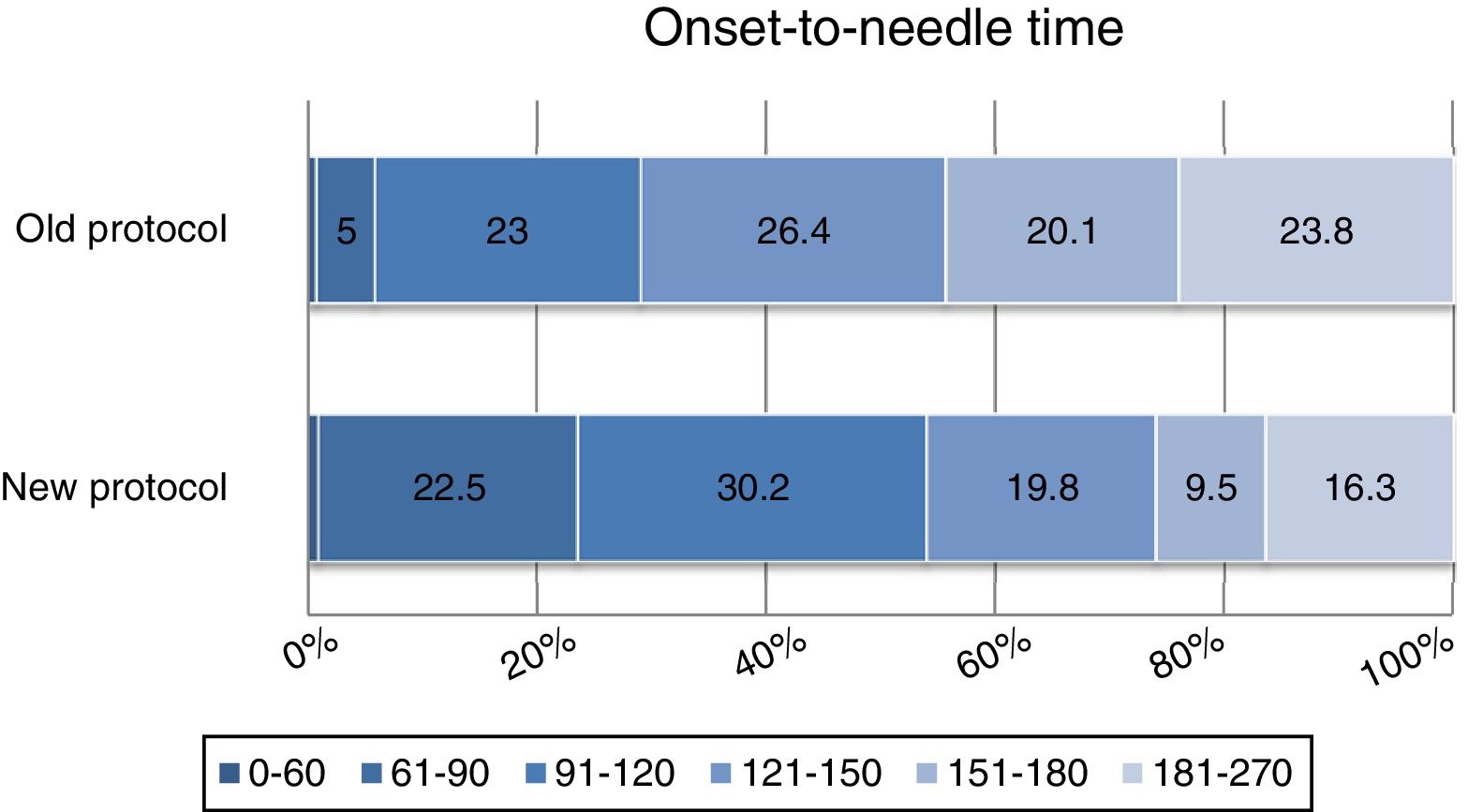

Under the old protocol, 5.8% of patients received treatment within 90minutes of symptom onset, 28.8% within 120minutes, and 75.3% within 180minutes. Under the new protocol, 23.4% of patients were treated within 90minutes of symptom onset (P<.001), 54.1% within 120minutes (P<.001), and 83.4% within 180minutes (P<.03) (Fig. 3).

Percentage of patients in each onset-to-needle time interval before and after implementation of the new protocol: 0-60min (P=.66), 61-90min (P<.001), 91-120min (P=.05), 121-150 (P=.06), 150-180 (P<.001), and 181-270min (P=.027). Treatment was administered within 90minutes of symptom onset in 5.8% of patients in the first period and 23.9% of patients in the second period (P<.001).

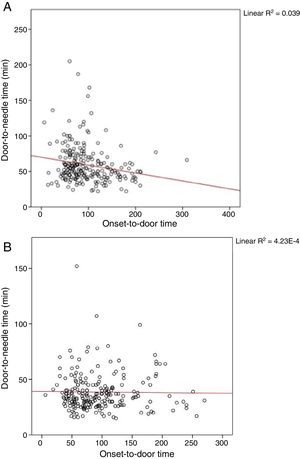

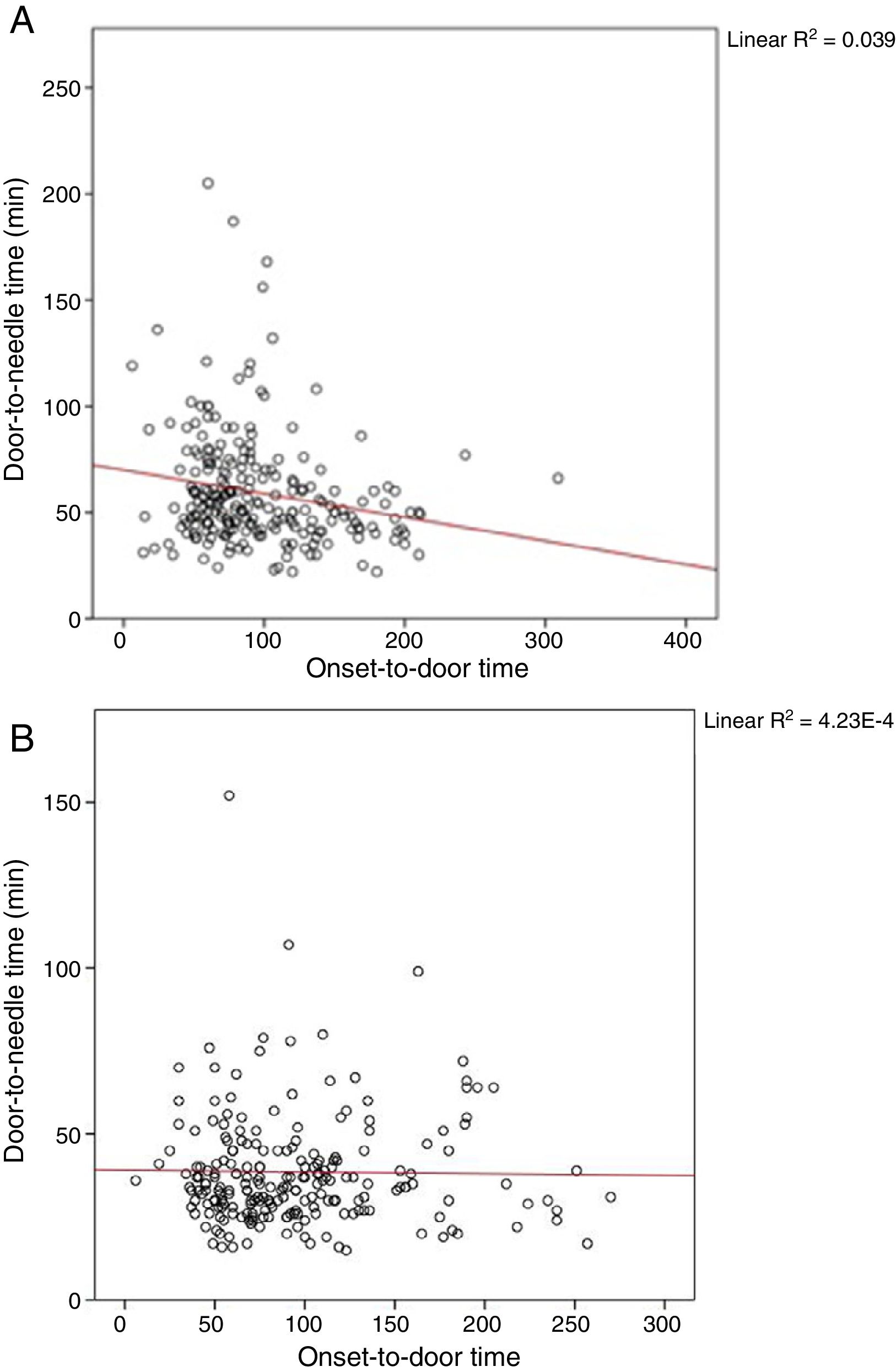

In the univariate regression analysis, neither age (P=.82) nor sex (P=.54) or baseline NIHSS score (P=.25) were found to have a significant impact on door-to-needle times under the old protocol. After the new protocol was implemented, no linear correlation was observed between onset-to-door time and door-to-needle time (B=–0.004; 95% CI, −0.047 to 0.040; P=.98); this correlation was observed under the old protocol, however (“3-hour effect”) (B=−0.125; P<.001) (Fig. 4). Two factors did continue to affect door-to-needle times after the implementation of the new protocol: use of CT angiography (B=17.31; 95% CI, 11.79-21.39; P<.001) and pre-hospital code stroke activation (B=−11.54; 95% CI, −16.75 to −6.32; P<.001).

Correlation between onset-to-door and door-to-needle times before (A) and after implementation of the new protocol (B). The inverse correlation between onset-to-door and door-to-needle times is known as the “3-hour effect”: patients with shorter symptom progression times, and thus more time to receive IV thrombolysis, are treated with less urgency. This effect disappeared with the implementation of the new protocol.

In the multivariate regression analysis, CT angiography studies performed before administration of IV thrombolysis continued to result in significantly longer door-to-needle times after the implementation of the new protocol (B=17.46; 95% CI, 11.36-21.24; P<.001); times were even proportionally longer than in the initial period (B=7.31; P=.03). However, CT angiography was performed before IV thrombolysis in fewer patients after the new protocol was introduced (34% vs 15.3%; P<.001). Pre-hospital code stroke activation continued to result in shorter management times (B=−11.36; 95% CI, −15.52 to −5.38; P<.001).

SafetyA total of 2.3% of patients treated with IV thrombolysis presented stroke mimics, and 2.7% presented symptomatic haemorrhagic transformation (vs 4.2% before the new treatment protocol; P=.63).

DiscussionAccording to our results, the implementation of a simple action protocol can significantly improve in-hospital stroke management times at a tertiary hospital. Although our centre's median door-to-needle times fell within the recommended 60-minute period, we consider this objective to be insufficient.3

The 60-minute window was established in 1995.18 The latest version of the AHA/ASA guidelines has updated this recommendation, advocating a door-to-needle time of < 45minutes for at least 50% of patients.12 The importance of time to treatment in acute stroke has been reaffirmed in successive clinical trials and meta-analyses of IV thrombolysis and endovascular treatment; this has led to an even more ambitious goal, a door-to-needle time of < 30minutes.11,19,20

Some “ultra-rapid” protocols have progressively reduced stroke management times, achieving a median door-to-needle time of 20minutes.9,10 However, no comparable in-hospital protocols have been developed in our setting.

Identifying the factors involved in long door-to-needle times at our centre and describing stroke management times constitute the starting point for our project.15 By gradually introducing a set of new measures, door-to-needle time has decreased to 27minutes (a 48% reduction in the last 4 months of the study vs the initial period) due to the consolidation of treatment with rtPA in the radiology room. Decreases were even more marked in cases of pre-hospital code stroke activation, for which the median door-to-needle time was 22minutes. Although proportionally fewer pre-hospital code stroke activations were recorded in the second period than in the first, onset-to-door times did not change significantly, whereas in-hospital times did decrease overall.

The introduction of the new protocol has also achieved a significant decrease in onset-to-needle time (26minutes), without any change in onset-to-door times. This is the most remarkable finding of our study, as the number needed to treat to obtain an optimal functional outcome (modified Rankin Scale scores of 0 or 1) is reported to increase by 1 for every 20minutes of onset-to-needle time.19 Furthermore, the number of patients treated within 90minutes of symptom onset increased significantly, with over 80% of patients treated within 3hours. This improvement in management times may increase the likelihood of good functional prognosis after treatment.21

According to several studies, performing a CT angiography study before administration of IV thrombolysis leads to in-hospital delays.9,22 In our centre, door-to-needle time was significantly longer in the initial period.15 Since the implementation of the new protocol, neuroimaging studies are performed before IV thrombolysis only in specific cases (Table 1). However, the door-to-needle time remained proportionally longer in the second period. This phenomenon has also been described in a hospital in Helsinki.9 It may be explained by the fact that CT angiography is only used in patients with uncertain diagnosis or more complex cases (e.g., suspected basilar artery occlusion). At present, since the introduction of rtPA bolus administration in the radiology room, CT angiography is performed immediately after onset of IV thrombolysis, with the patient on the examination table. Not only does this approach not delay rtPA treatment onset, it also allows immediate identification of patients eligible for endovascular treatment.9,10,19

Updating in-hospital protocols and decreasing door-to-needle times is also essential for timely endovascular treatment, and should be considered when designing stroke management plans with the mothership or the drip and ship models.23

According to the “3-hour effect,” patients with shorter symptom progression times, who consequently have more time to receive IV thrombolysis, are treated with less urgency. This inverse correlation between onset-to-door and door-to-needle times was identified as a factor involved in in-hospital delays and has disappeared with the new protocol. To this end, special emphasis was placed on promoting motivation and adherence to the protocol among on-call neurologists; this measure has previously been shown to be effective in other Spanish hospitals.24

Regarding the safety of the new protocol, no significant differences were observed in the number of cases of haemorrhagic transformation between the 2 periods, and the number of patients with stroke mimics receiving thrombolysis is similar to those reported in other series.9

The efficacy of each of the measures included in the new protocol has been analysed in a previous article. Requesting complementary tests and reviewing the patient's clinical history before their arrival at the hospital reduced the median door-to-CT time by up to 2minutes in patients with code stroke activation, whereas not performing an additional electrocardiography study reduced it by up to 5minutes. Furthermore, performing CT angiography after IV thrombolysis and not waiting for the results of the coagulation study were independent predictors of shorter CT-to-needle and door-to-needle times. This suggests that performing every step of the protocol in sequential order is essential to achieving optimal results.16

Our study has a number of limitations: it was performed in a single centre; the new measures could not be applied in all cases for various reasons (pre-hospital code stroke was not activated, adherence to the protocol was not optimal during the early phases, protocol measures were not introduced simultaneously, etc.)16; and the complete protocol was applied only in the last 4 months of the study. We expect in-hospital management times to continue decreasing due to training of the stroke team. Although the median door-to-needle time is currently below the 30minutes recommended in the literature, the interquartile range remains large. This may be explained by the fact that our study included patients for whom pre-hospital code stroke had not been activated, as well as more complex cases (e.g., posterior circulation stroke) that are excluded from other series.9 New measures are currently being studied to continue reducing stroke management times; these include direct transfer of the patient to the radiology room upon arrival at the hospital. In 2016, median door-to-needle times increased slightly as compared to the previous year. During that year, feedback sessions were held on a less regular basis. Anecdotally, our experience suggests that the motivation of the healthcare team plays a pivotal role in maintaining improvements in stroke management times. Our initial objective was to reduce door-to-needle times; therefore, we did not analyse door-to-femoral puncture time. However, as the measures included in the new protocol assist in the selection of candidates for endovascular treatment, door-to-femoral puncture time is also likely to have decreased. Future studies should also analyse this parameter.

In conclusion, the measures implemented were found to effectively reduce in-hospital stroke management times and even total time to treatment with IV thrombolytics. Motivation, training, and team work are key factors in the success of our protocol. Updating in-hospital protocols and reducing door-to-needle times is also essential in providing timely endovascular treatment. At present, there remains room for improvement; according to our experience, door-to-needle times of less than 30minutes should be the goal of stroke units.

FundingThe study received funding from the Gregorio Marañón Healthcare Research Institute.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the neurology residents at Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón for their enthusiasm and dedication to this project.

We also wish to thank all healthcare professionals at Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, who, under the motto “time is brain,” have helped in the implementation and daily running of the new protocol.

Please cite this article as: Iglesias Mohedano AM, García Pastor A, Díaz Otero F, Vázquez Alen P, Martín Gómez MA, Simón Campo P, et al. Un nuevo protocolo intrahospitalario reduce el tiempo puerta-aguja en el ictus agudo tratado con trombolisis intravenosa a menos de 30 minutos. Neurología. 2021;36:487–494.

![In the last 3 months of the study period (when all protocol measures had come into force, including administration of rtPA in the radiology room and extension of the schedule for administration [8:00-22:00]), door-to-needle time was < 30minutes. Door-to-needle time decreased as the number of patients starting rtPA treatment in the radiology room increased. In the last 3 months of the study period (when all protocol measures had come into force, including administration of rtPA in the radiology room and extension of the schedule for administration [8:00-22:00]), door-to-needle time was < 30minutes. Door-to-needle time decreased as the number of patients starting rtPA treatment in the radiology room increased.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735808/0000003600000007/v1_202109160551/S2173580820300134/v1_202109160551/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)