‘Chronic pelvic pain’ refers to pain affecting the area below the navel and lasting at least 6 months; pain is severe enough to cause functional disability or require specialised medical treatment. Perineal pain is frequently caused by a lesion to the anatomical structures passing through the Alcock canal. However, there are many causes of this type of pain apart from pudendal neuropathy or pudendal nerve entrapment; involvement of the endopelvic portion of the pudendal nerve or the sacral nerve roots may also cause perineal or perianal pain. Alcock canal syndrome was first described in 1987 in male cyclists with genital and sphincter dysfunction, associated in some cases with transient genital and perineal paraesthesia/hypoaesthesia secondary to prolonged compression of the pudendal nerve where it passes through the Alcock canal.1

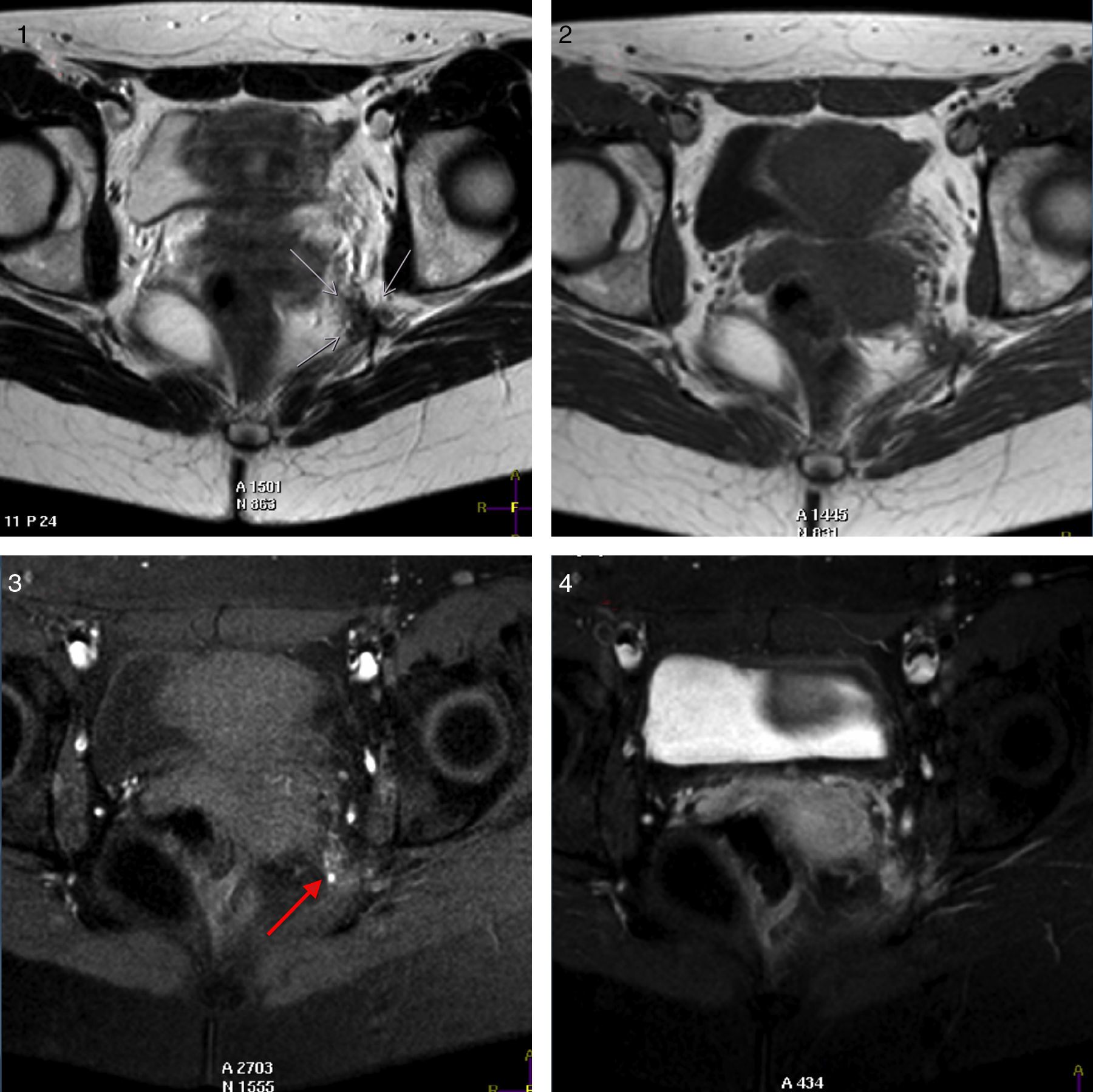

We present the case of a 30-year-old woman with no relevant history of trauma or gynaecological diseases who reported sudden-onset, recurrent pain in the perineal and left-sided internal gluteal regions. Pain was described as stabbing, tingling, and burning; the patient experienced hypersensitivity exacerbated by touch or sitting and ameliorated by standing or lying. Our patient reported no urethral or anal sphincter dysfunction or incontinence. Pain was intense and always affected the same anatomical region; it always reappeared mid-cycle and at onset of menstruation, after which it would persist, with fluctuations, for several days. The patient underwent a physical examination of the genital and perineal area and reported intense pain during a digital rectal exam, which exacerbated upon mobilisation of the cervix. Vaginal examination revealed presence of a band of fibrous tissue in the left ischial spine which was extremely painful on palpation; this structure was not detected in the contralateral area. Cutaneous examination of the left perineal area revealed hyperalgesia and positive Tinel sign; there was no clear hypoaesthesia in the area, and anal and bulbocavernosus reflexes were preserved. In light of our patient's medical history and the findings from the examination, we decided to conduct a complementary neuroimaging study to detect any endometrial lesions able to cause the symptoms reported by the patient. The gynaecological ultrasound study detected no relevant structural alterations. Our patient refused to undergo neurophysiological testing of the affected area. However, in view of her persistent clinical symptoms, she underwent a pelvic MRI scan with and without contrast during the menstrual period which revealed a haemorrhagic lesion in the lower part of the pelvic wall, at the level of the entry site of the left pudendal nerve into the Alcock canal; this finding was compatible with endometriosis (Fig. 1).

T1- and T2-weighted axial sequences (1, 2). T1-weighted fat-saturated images before and after gadolinium injection (3, 4). T2-weighted imaging displays a hypointense spiculated lesion in the pelvic floor (white arrows), in the left pelvic wall, and at the entry site of the pudendal nerve into the Alcock canal. The lesion (white arrows) shows moderate signal intensity in T1-weighted and T1-weighted fat-saturated sequences. Remnants of haemorrhage are hyperintense (red arrow in 3). Gadolinium uptake in the lesion is heterogeneous (4). Colour images are available in the electronic version of this article.

The pudendal nerve originates in the sacral plexus and exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, running below the sacrospinous ligament and through the lesser sciatic foramen to reach the perineum, accompanied by its associated neurovascular structures. Once in the ischioanal fossa, the pudendal nerve, artery, and vein all pass through the Alcock canal.2 At this point, the pudendal nerve divides into 3 terminal branches (inferior rectal nerve, perineal nerve, and dorsal nerve of the penis/clitoris), each with motor, sensory, and autonomic fibres; compression of the pudendal nerve may therefore result in motor, sensory, or autonomic symptoms.3 The most frequent cause of pudendal nerve damage is trauma leading to stretching, compression, or secondary fibrosis of the nerve. Endometriosis, a frequent gynaecological disease affecting millions of women worldwide, has been described as a possible cause of sacral radiculopathy.4 Although the literature includes only a few cases, sacral plexus and pudendal and sciatic nerve involvement secondary to endometriosis may be a frequent cause of anal, genital, and pelvic pain.5,6 Isolated endometriosis of the sciatic nerve and endometriosis of the sacral nerve roots appear to be different entities with distinct clinical and surgical features. Isolated endometriosis of the sciatic nerve is always located at the supra-piriform portion of the sciatic nerve (L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots); associated symptoms include sciatica, gluteal pain, and locomotor disability (foot drop), but no bladder dysfunction or pain in areas innervated by the pudendal nerve. Endometriosis of the sacral nerve roots, on the other hand, results from deep endometriosis infiltrating the parametrium. Given the proximity of other anatomical structures, infiltration of the uterosacral ligaments may involve sacral roots S3 and S4, whereas infiltration of the cardinal and ovarian ligaments is associated with involvement of sacral roots S2 and S3. The most frequent neurological symptom is pain in areas innervated by the pudendal and gluteal nerves (sacral roots S3 and S4); patients with endometriosis of the sacral nerve roots never display locomotor alterations.4

Management of patients with pudendal neuropathy includes medical treatment, pelvic and perineal rehabilitation therapy, and surgery. The most frequently used drugs are antidepressants (amitriptyline), neuromodulators (gabapentin, pregabalin), and local anaesthetics (lidocaine gel). In many cases, perineural injection of corticosteroids and lidocaine/bupivacaine improves symptoms significantly by relaxing hypertonic sphincters and resolving bladder symptoms and sexual dysfunction. In cases of peripheral nervous system dysfunction, dry needling and local lidocaine infiltrations may help deactivate trigger points of the affected pelvic floor muscles and reduce symptoms. Pudendal nerve decompression surgery is only offered to those patients whose symptoms are refractory to medical treatment and physical therapy.7 Regarding treatment for endometriosis, hormone therapy is recommended when the affected areas are small or symptoms are mild, whereas surgery is preferred when the patient does not respond to hormone therapy, lesions are extensive, or symptoms are severe.8 In our patient, treatment with amitriptyline and several neuromodulators reduced symptoms only partially and caused adverse effects which limited the effectiveness of these drugs. Perineural injection of corticosteroids and anaesthetics improved symptoms temporarily, although pain returned with every new menstrual cycle. Our patient started hormone therapy while waiting to undergo decompression surgery; during that period, she became pregnant and remains completely asymptomatic to date.

Please cite this article as: Maestre-Verdú S, Medrano-Martínez V, Pack C, Fernández-Izquierdo S, Francés-Pont I, Mallada-Frechin J, et al. Síndrome del canal de Alcock secundario a infiltración por endometriosis. Neurología. 2017;32:264–266.