Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS) is a rare neurological disorder involving symptoms related to alteration in visuotemporal perception that may include dysmorphopsia (vertical lines appearing wavy), porropsia (stationary objects receding), time distortions, derealization, and depersonalization, among others.1 First noticed as visual migraine symptoms, these perceptual distortions were finally grouped by John Todd, who coined the term AIWS in 1955.2 The symptoms may last minutes to several days and resolve ad integrum.1

Many underlying etiologies have been suggested, such as migraine, epilepsy, substance abuse, central nervous system lesions, and infections (including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease).1–3 Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and by excluding other primary causes, usually corroborated through ancillary tests.1–3 However, our knowledge of the numerous causes, manifestations, and pathophysiology of AIWS is still in its infancy.3

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) may present with diverse clinical symptoms, including visual disturbance, headache, seizures, and impaired consciousness.4 The pathogenesis behind PRES is not clearly understood, but hypertensive crises, renal failure, eclampsia, cytotoxic drugs, neoplasms, and autoimmune conditions have been implied.4 PRES in patients with multiple myeloma has rarely been described.5–9 The triggering factors in this type of patient could be neurotoxicity, chemotherapy, or the disease itself.5–9 Recently, metamorphopsia and macropsia have been reported with the recovery of PRES in a suspected case of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.10 However, AIWS in the backdrop of multiple myeloma and PRES, has not been published.

The authors herein report the chronicle of a patient who was initially diagnosed as a case of AIWS, in whom further relevant workups and neuroimaging revealed PRES in the presence of multiple myeloma.

A 60-year-old woman was brought to the emergency department by family members for intermittent abnormal behavior and persistent holocranial headache for the last 2 days. Her past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The patient complained of episodic distorted perceptions of visualized objects and people in size, depth, motion, color, and distance (i.e., sudden visualization of known persons receding or increasing to an unnatural extent; seeing objects placed at a known distance, either far away or too close; perceiving moving cars on roads as abruptly accelerating, decelerating, or coming to a standstill; perceiving straight roads appeared curvy; colorful objects appearing either colorless or extremely bright) and distorted perception of sounds. These symptoms were present for the last week, persistent for 10-12 minutes, resolved independently, and were not frightening. Apart from headaches, these episodes had no other accompanying symptoms. According to her family members, she had been suffering from persistent low back pain for the last six months, for which few consultations were taken without definite improvement.

Except for pallor, no other significant abnormality was found in the general and ophthalmological examinations. A complete neurological analysis revealed no significant abnormality except higher-order visual processing disorder (micropsia/macropsia, dysmorphopsia/metamorphopsia, akinetopsia/hyperkinetopsia, dyschromatopsia, and teleopsia/pelopsia).

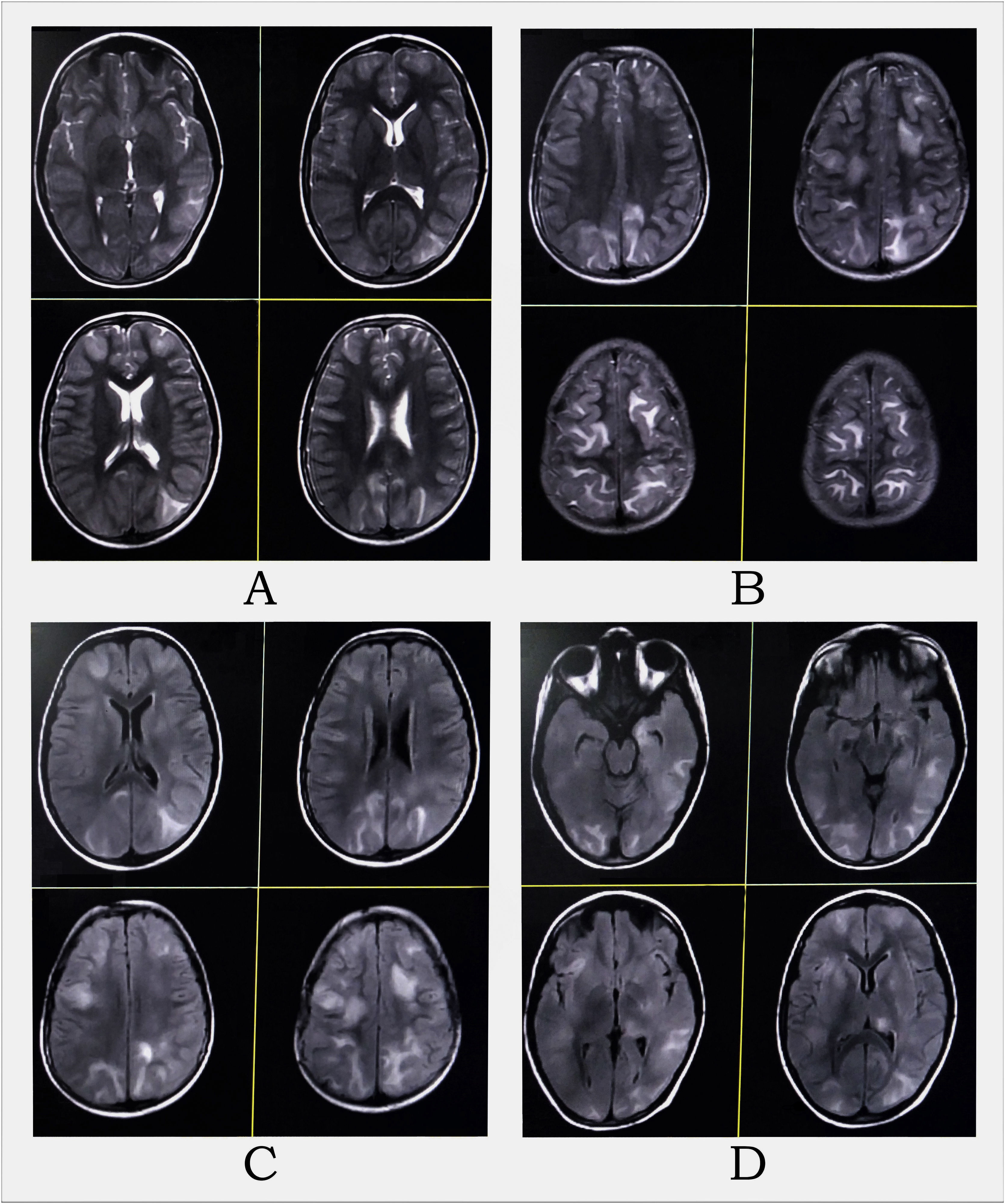

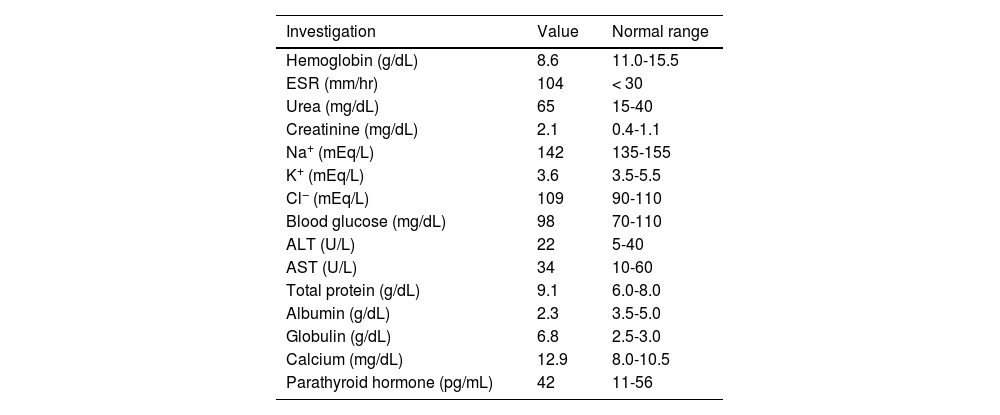

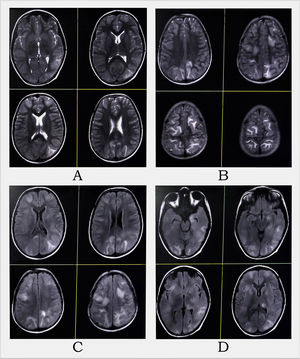

Complete hemogram and metabolic panel results are listed in Table 1, and revealed anemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, remarkably high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, azotemia, and hypercalcemia. Arterial blood pressure ranged from 114/70 to 134/80 mmHg throughout the admission. The electrocardiogram showed a short QT interval. An awake and sleep electroencephalogram was otherwise normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain suggested PRES (Fig. 1). Hypercalcemia-induced PRES was the likely possibility as the patient had no other traditional risk factors. Besides, the involvement of the bilateral posterior parietal and occipital cortex due to PRES might have given rise to episodic higher-order visual processing difficulties.

Blood investigations.

| Investigation | Value | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.6 | 11.0-15.5 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 104 | < 30 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 65 | 15-40 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.1 | 0.4-1.1 |

| Na+ (mEq/L) | 142 | 135-155 |

| K+ (mEq/L) | 3.6 | 3.5-5.5 |

| Cl− (mEq/L) | 109 | 90-110 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 98 | 70-110 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22 | 5-40 |

| AST (U/L) | 34 | 10-60 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 9.1 | 6.0-8.0 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.3 | 3.5-5.0 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 6.8 | 2.5-3.0 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 12.9 | 8.0-10.5 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | 42 | 11-56 |

MRI of the brain revealed multifocal altered intensity lesions, hyperintense on T2-WI (A and B) and T2-FLAIR (C and D) at regions of both frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes; left temporal lobe, and left thalamus, mostly involving cortical and subcortical U-fibers with mass effect over adjoining sulci.

Low back pain for such duration, anemia, hypercalcemia, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and renal impairment pointed towards the possibility of plasma cell disorders. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed an M-spike in the beta region. MRI of the spine revealed infiltrative marrow disease. A bone marrow biopsy showed a high percentage of plasma cells, confirming the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. She was put on intravenous normal saline, torsemide, and zolendronic acid. On day seven, after normalization of hercalcium level, she was put on bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone.

This case is unique because the patient initially presented with recent-onset metamorphopsias and headache. Still, from her history of chronic back pain and targeted laboratory investigations, it was finally diagnosed as a case of PRES in the backdrop of multiple myeloma.

AIWS differs from other perceptual disorders in that the waking individual experiences distortions based on an appropriate stimulus from the outside world, in which “a particular aspect is altered consistently”.11 AIWS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Recently, Shammas12 proposed a classification system of AIWS based on the subtypes of the distortions, namely 1) visual, 2) temporal, 3) intrapersonal or body-image changes, and 4) miscellaneous. From a pathophysiological viewpoint, lesions (structural or functional) in different parts of the perceptual network can cause perceptual distortions, e.g., area V4 (hyperchromatopsia) and area V5 (akinetopsia).13 The diverse potential etiologies warrant an extensive workup.2

PRES is mainly observed in patients with hypertensive crises. The increased blood pressure causes cerebral hyper-perfusion, leading to vascular leakage and edema. The susceptibility of the posterior regions of the brain to vasomotor dysregulation may be due to the lack of sympathetic innervation.14 White matter is less densely packed than cortical regions, and hence the changes are usually observed there. However, this mechanism does not explain the PRES in normotensive patients (like ours). A second mechanism is that a sudden change in pressure leads to cerebral vasoconstriction, ischemia, and cytotoxic edema. Nevertheless, PRES has also been observed in malignancies, renal disorders, cytotoxicity, and chemotherapy because of endothelial dysfunction. Recently, COVID-19, scrub typhus, and snakebite envenomation have also been discussed as etiologies of PRES.15–17 PRES is potentially reversible with prompt management; however, some cases convey substantial morbidity and mortality.14

Unlike previous cases,5–9 the current case is the first where PRES occurred in the presence of multiple myeloma before receiving any treatment. Although extremely rare, the possibility of PRES and multiple myeloma must be considered in AIWS in the presence of telltale signs and a suggestive laboratory workup. AIWS is benign in most cases and resolves spontaneously, but proper diagnostic workup must be carried out before coming to definitive conclusions.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled criterion as established by the ICMJE.

Study fundingNil.

Ethics statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and any accompanying images.

DisclosuresDr. Ritwik Ghosh: reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Moisés León-Ruiz: reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Dipayan Roy: reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Kunal Bole: reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Julián Benito-León: reports no relevant disclosures.

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD—platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451).