Telephone assistance is a common practice in neurology, although there are only a few studies about this type of healthcare. We have evaluated a Telephone Assistance System (TAS) for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) from 2 points of view: financially and according to the level of satisfaction of the caregiver.

Patients and methods97 patients with a diagnosis of AD according to NINCDS-ADRDA criteria and their 97 informal caregivers were selected. We studied cost differences between on-site assistance and telephone assistance (TAS) for 12 months. We used a self-administered questionnaire to assess the level of satisfaction of caregivers at the end of the study period.

ResultsTAS savings amounted to 80.05±27.07 euros per user. 73.6% of the caregivers consider TAS a better or much better system than on-site assistance, while only 2.6% of the caregivers considered TAS a worse or much worse system than on-site assistance.

ConclusionsTelephone assistance systems are an efficient healthcare resource for monitoring patients with AD in neurology departments. Furthermore, the level of user satisfaction was high. We therefore consider that telephone assistance service should be offered by healthcare services.

La asistencia telefónica a demanda (ATAD) es una práctica habitual en las consultas de Neurología; no obstante, los estudios que valoran dicha modalidad de asistencia sanitaria son escasos. Hemos evaluado la ATAD en cuidadores de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) desde el punto de vista económico y de la satisfacción percibida por el cuidador principal.

Pacientes y métodosSe seleccionó a 97 pacientes con diagnóstico de EA según criterios NINCDS-ADRDA y sus respectivos 97 cuidadores principales. Estudiamos los gastos diferenciales entre las modalidades asistenciales presencial y a demanda a lo largo de 12 meses. A los 12 meses se valoró la satisfacción de los cuidadores principales mediante un cuestionario autoadministrado.

ResultadosEl ahorro que supuso la ATAD frente la asistencia presencial fue de 80,05±27,07 euros por usuario. Al 73,6% de los cuidadores que usaron la ATAD les parece mejor o mucho mejor esta que la asistencia presencial, mientras que al 2,6% de los cuidadores les parece peor o mucho peor.

ConclusionesLa ATAD supone un servicio de salud eficiente en el seguimiento de los usuarios con EA en las consultas de Neurología y la satisfacción de los usuarios fue alta, por lo que consideramos que debería incluirse en la cartera de servicios del sistema sanitario.

The telephone has been used for various purposes in the field of healthcare in general, and in neurology in particular, including for remote medical consultations as an alternative to in-person consultations for patients with difficulties accessing healthcare.1 Experts agree that patients in advanced stages of Alzheimer disease (AD) can be followed up by telephone on demand.2–4 Several studies have shown that telemedicine as a vehicle for information and support, whether on demand or as part of a follow-up schedule, improves carers’ quality of life.5–8

Telephone assistance is an unstructured, informal practice frequently used in neurology departments. This approach provides timely responses to users’ problems, increasing accessibility and helping overcome spatial and temporal barriers. However, it does have several disadvantages: physicians may not have the required clinical data immediately available to give a response; consultations are not recorded or quantified in databases; and telephone calls often interrupt in-person consultations.

Telephone assistance provided to patients with different neurological diseases usually results in a high level of satisfaction9,10 and has objective advantages: it reduces travel times and costs associated with transportation to the healthcare centre.1

Applying new technologies to clinical practice requires rigorous studies following the stipulations of health technology agencies.11,12 The benefits of these new technologies for carers, though small, have been extensively demonstrated. Evidence of their efficiency, however, is more controversial.13

Few studies have addressed the use of the telephone for healthcare provision, especially in our setting, and none of them have evaluated these systems in economic terms.14–16 Our study provides a prospective economic evaluation of telephone assistance (cost minimisation analysis) and assesses user satisfaction with telephone assistance systems (TAS).

Patients and methodsThe TAS project, developed in our dementia unit, provides primary carers of AD patients with the telephone number of the hospital liaison nurse, whom they can contact during working hours. The liaison nurse notifies the neurologist of the telephone calls he or she receives; within 24 hours, the neurologist provides telephone assistance using the patient's digital clinical history and the electronic prescription system.

We conducted a prospective observational study of 97 patients diagnosed with AD plus their carers (n=97), who were identified as primary carers (PC).

Patients were recruited consecutively from the dementia unit of the neurology department at Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria. Patients met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Participants were selected by purposive or convenience sampling from January 2014 to May 2014; all participants were followed up for 12 months. The study ended in May 2015.

Patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: having a diagnosis of AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA diagnostic criteria and displaying mild-to-moderate AD according to the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST; stages 6c or lower). Patients with other types of dementia and those at severe stages of AD (FAST stages 6d or higher) were excluded from the study. All participating patients had visited the neurology department at our hospital on at least 2 occasions and were receiving specific symptomatic treatment for AD. Each patient had a primary carer. Patients living in geriatric residences and those patients or caregivers who may have been unable to undergo follow-up assessments in the following 12 months were excluded.

All PCs signed informed consent forms after receiving oral and written information about the study. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the province of Málaga.

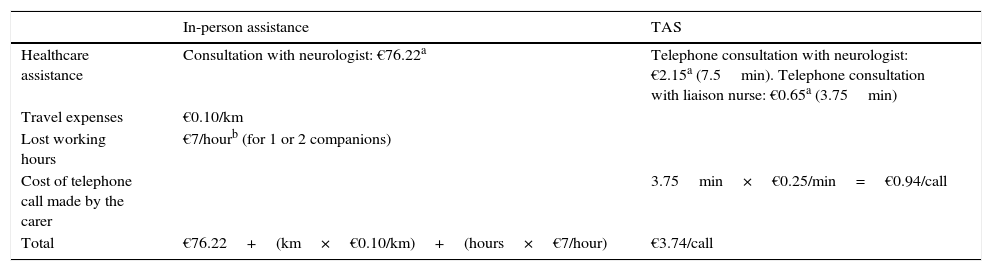

The variables necessary to calculate the costs associated with TAS and in-person consultations were determined at the baseline consultation (Table 1). TAS costs were calculated based on the daily cost of a neurologist and a liaison nurse (€120.70/day and €72.73/day, respectively, according to data from our hospital's accounting analytics system), and the amount of time invested by the neurologist and the liaison nurse in telephone consultations. Telephone consultation time was estimated empirically and based on the recommended times for in-person follow-up consultations. The resulting estimates were 7.5 minutes for consultations with the neurologist and 3.75 minutes for consultations with the liaison nurse. Travel costs were estimated with the Google Maps application, which was used to calculate the driving distance between the user's place of residence and the city of Málaga. The remaining data were gathered from the patient's clinical history or reported by his or her carer; the latter reported whether a companion was necessary.

Costs associated with in-person and telephone assistance.

| In-person assistance | TAS | |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare assistance | Consultation with neurologist: €76.22a | Telephone consultation with neurologist: €2.15a (7.5min). Telephone consultation with liaison nurse: €0.65a (3.75min) |

| Travel expenses | €0.10/km | |

| Lost working hours | €7/hourb (for 1 or 2 companions) | |

| Cost of telephone call made by the carer | 3.75min×€0.25/min=€0.94/call | |

| Total | €76.22+(km×€0.10/km)+(hours×€7/hour) | €3.74/call |

TAS: telephone assistance systems.

We recorded all telephone calls received by the liaison nurse and passed on to the neurologist during the 12 months that the TAS were available to carers. We also recorded the reason for telephone consultations and how they were resolved.

At 12 months, an in-person follow-up consultation was scheduled and communicated by post; carers had to complete a satisfaction survey after the follow-up consultation. The survey included 5 questions: the first 3 concerned the carer's experience with TAS, whereas the last 2 addressed the carer's opinion on TAS and in-person consultations (these 2 questions were also completed by carers not using TAS). Questions were closed-ended and offered several mutually-exclusive response options (Likert-type).

Data were recorded in a notebook with an identifying code. All data were masked. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software version 20.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of patients’ and carers’ sociodemographic, clinical, and caregiving variables. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and continuous variables as means±SD and minimum and maximum values, with a 95% confidence interval.

ResultsWe included 97 patients with their PCs; 11 PCs (11.34%) were lost to follow-up. Losses to follow-up were due to the patient's death in 5 cases, institutionalisation in 3, repeated failure to attend medical appointments and/or answer telephone calls in 2, and the PC's admission to hospital in one case. The satisfaction survey, however, was completed by all PCs but 5 (5.15%), given that the carers lost to follow-up had used the TAS and could therefore rate their experience. All PCs meeting the inclusion criteria owned a telephone (mobile or landline) and agreed to participate in the study.

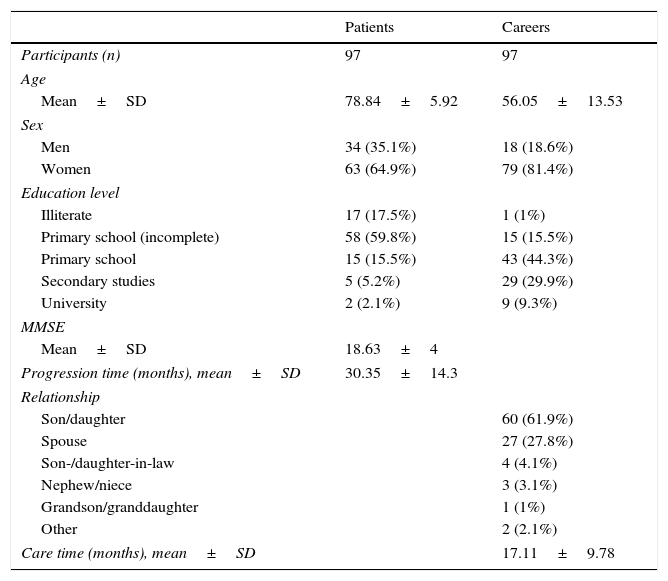

Table 2 summarises sociodemographic, clinical, and caregiving characteristics of our sample. PCs had a mean age of 56.05 years (range, 26-87 years). PCs were classified according to whether or not they were of similar age to their patients; mean age of coetaneous and non-coetaneous PCs was 72.9 years and 48.9, respectively. Of all PCs, 86.7% of those who were patients’ children and 70.4% of those who were spouses were women.

Participants’ sociodemographic, clinical, and caregiving characteristics.

| Patients | Careers | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 97 | 97 |

| Age | ||

| Mean±SD | 78.84±5.92 | 56.05±13.53 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 34 (35.1%) | 18 (18.6%) |

| Women | 63 (64.9%) | 79 (81.4%) |

| Education level | ||

| Illiterate | 17 (17.5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Primary school (incomplete) | 58 (59.8%) | 15 (15.5%) |

| Primary school | 15 (15.5%) | 43 (44.3%) |

| Secondary studies | 5 (5.2%) | 29 (29.9%) |

| University | 2 (2.1%) | 9 (9.3%) |

| MMSE | ||

| Mean±SD | 18.63±4 | |

| Progression time (months), mean±SD | 30.35±14.3 | |

| Relationship | ||

| Son/daughter | 60 (61.9%) | |

| Spouse | 27 (27.8%) | |

| Son-/daughter-in-law | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Nephew/niece | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Grandson/granddaughter | 1 (1%) | |

| Other | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Care time (months), mean±SD | 17.11±9.78 | |

SD: standard deviation; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; n: sample size.

Thirty-eight of the 97 participating PCs (39.2%) used the TAS at least once, resulting in a total of 55 telephone calls (1.45 calls per PC using the TAS). The mean number of telephone calls per PC in the total sample was 0.6. Most PCs called once; calling more than twice was anecdotal.

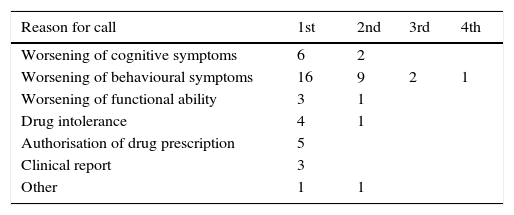

The main reason for telephone consultation was worsening of behavioural symptoms (50.9%); furthermore, this was the only cause leading to more than 2 telephone calls (in 2 cases; 3 and 4 calls). Other reasons for telephone consultations, in decreasing order of frequency, were as follows: worsening of cognitive symptoms, requesting prior authorisation for prescription drugs, drug intolerance, worsening of functional ability, and requesting clinical reports (Table 3).

Reasons for telephone consultation and problem resolution.

| Reason for call | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worsening of cognitive symptoms | 6 | 2 | ||

| Worsening of behavioural symptoms | 16 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| Worsening of functional ability | 3 | 1 | ||

| Drug intolerance | 4 | 1 | ||

| Authorisation of drug prescription | 5 | |||

| Clinical report | 3 | |||

| Other | 1 | 1 |

| Resolution | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advice | 7 | |||

| Dose adjustment | 6 | 6 | 1 | |

| Adding drugs | 9 | 5 | 1 | |

| Discontinuing drugs | 1 | |||

| Changing drugs | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Authorisation of drug prescription | 5 | |||

| Clinical report | 3 | |||

| Scheduling in-person consultation | 5 | 1 |

Telephone consultations were most frequently resolved by prescribing additional drugs (27.27%). The resolution of 61.82% of telephone consultations was linked to drug changes (adjusting the dose; adding, discontinuing, or changing a drug). Eight calls were resolved by issuing clinical reports or authorising drug prescription. Six calls (11%) were resolved by scheduling in-person consultations within a week to assess patients (Table 3).

Travel costs to attend in-person consultations were calculated individually: 1) users travelling to the healthcare centre by their own means (n=89) lived at a mean distance of 25.37km from the city of Málaga; and 2) the remaining 8 users travelling by other means of transportation (bus, metro, taxi) incurred a mean direct cost of €31.02. Lost working hours (for as many companions as necessary) totalled 49, spread between 11 carers.

The cost of TAS during the 12 months of follow-up corresponded to the 55 telephone calls made by PCs and the 6 in-person follow-up consultations derived from those calls. The mean total costs of TAS amounted to €3.74 per consultation (Table 1). The cost of the 6 in-person consultations was calculated based on the mean cost of baseline in-person consultations for the 97 participants (€86.87).

The t test showed a statistically significant difference between means (P<.001), with a mean of €80.50±27.07 (95% CI, 75.05-85.96). We applied sensitivity analysis to the cost of telephone assistance; this parameter was multiplied by 10, since it was likely to be the most underrated parameter in our study. As a result, the cost of each telephone consultation was €6.50 for consultations with the liaison nurse and €21.50 for consultations with the neurologist (these values were obtained by multiplying by 10 the costs of telephone assistance shown in Table 1). After applying these new values to TAS, the cost per telephone call amounts to €28.94 (including €0.94 corresponding to the cost of the telephone call made by the carer). Maintaining the remaining data, the mean cost per patient amounts to €24.60 (instead of €8.35). Considering these values, TAS entails a saving of €62.27 per user compared to in-person assistance.

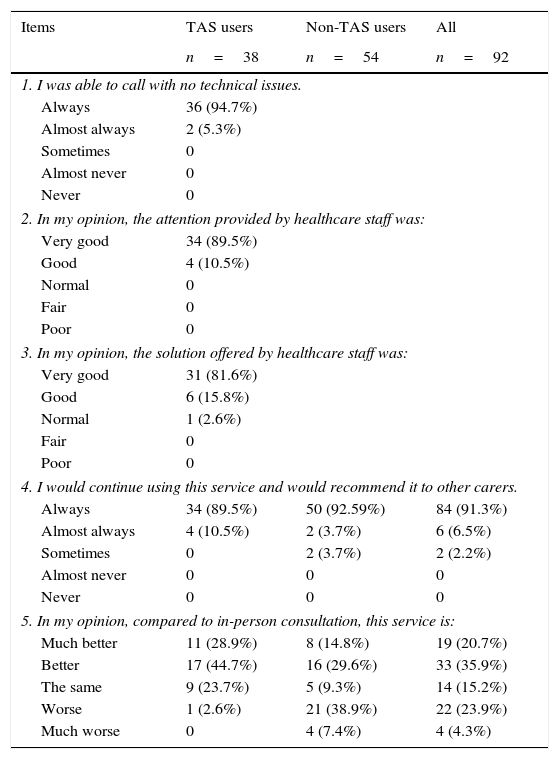

The 38 PCs using TAS had to complete the first 3 items of the satisfaction survey; responses were favourable or very favourable in over 90% of cases. Favourable opinions of TAS were more frequent among non-coetaneous carers (the only carer who rated TAS poorly was coetaneous) (Table 4).

Satisfaction survey for primary carers.

| Items | TAS users | Non-TAS users | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=38 | n=54 | n=92 | |

| 1. I was able to call with no technical issues. | |||

| Always | 36 (94.7%) | ||

| Almost always | 2 (5.3%) | ||

| Sometimes | 0 | ||

| Almost never | 0 | ||

| Never | 0 | ||

| 2. In my opinion, the attention provided by healthcare staff was: | |||

| Very good | 34 (89.5%) | ||

| Good | 4 (10.5%) | ||

| Normal | 0 | ||

| Fair | 0 | ||

| Poor | 0 | ||

| 3. In my opinion, the solution offered by healthcare staff was: | |||

| Very good | 31 (81.6%) | ||

| Good | 6 (15.8%) | ||

| Normal | 1 (2.6%) | ||

| Fair | 0 | ||

| Poor | 0 | ||

| 4. I would continue using this service and would recommend it to other carers. | |||

| Always | 34 (89.5%) | 50 (92.59%) | 84 (91.3%) |

| Almost always | 4 (10.5%) | 2 (3.7%) | 6 (6.5%) |

| Sometimes | 0 | 2 (3.7%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| Almost never | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Never | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. In my opinion, compared to in-person consultation, this service is: | |||

| Much better | 11 (28.9%) | 8 (14.8%) | 19 (20.7%) |

| Better | 17 (44.7%) | 16 (29.6%) | 33 (35.9%) |

| The same | 9 (23.7%) | 5 (9.3%) | 14 (15.2%) |

| Worse | 1 (2.6%) | 21 (38.9%) | 22 (23.9%) |

| Much worse | 0 | 4 (7.4%) | 4 (4.3%) |

TAS: telephone assistance systems; n: sample size.

In the context of our study, TAS were found to be highly valid and reliable for diagnosing and treating patients with AD for 2 main reasons: 1) the participating patients had been assessed clinically at neurology consultations at least twice, had a diagnosis of AD, and received specific treatment; and 2) digital clinical histories for all users and electronic prescriptions were immediately available. Furthermore, other published studies of in-person and ICT-based interventions report similar results.17,18

In our study, use of TAS was limited (0.6 calls per carer). No overuse of TAS was seen, with only 15.22% of carers calling more than once. The carers calling more than once, and especially those calling more than twice, probably care for patients with psychological disorders which are difficult to manage or result in a high caregiving burden. TAS may help physicians detect this subgroup of carers, enabling more personalised, proactive support, rather than providing support only when requested by carers themselves.

Cost savings associated with TAS amounted to €80 per patient, corresponding mainly to the cost of the in-person follow-up consultation. For users, in-person consultations cost nearly €8.00 more than telephone consultations. Applying a sensitivity analysis to the cost of telephone assistance, both for calls with the neurologist and with the liaison nurse, reduced cost savings to €62.27 per patient. Reducing costs may help rationalise in-person follow-up neurology consultations and adapt them to users’ needs, with savings to be invested in more effective interventions.19,20

In our study, the estimated costs associated with in-person follow-up consultations and lost working hours are lower than those in other studies conducted in our setting, which adds consistency to our results.21,22

Carer satisfaction with TAS in terms of the technology, the service received, and the solution offered (first 3 items) was very high; this may be due in part to the widespread use of telephones and the normality of telephone communication among the general population. Most carers, whether TAS users or not, recommended the system (item 4). This may be explained by the fact that TAS provide users with a service. Regarding item 5, 73.6% of users considered TAS to be better or much better than in-person assistance; their opinion is greatly influenced by their own experience, the immediacy of TAS, and resolution of their problems. In the retrospective study by Toribio-Diaz et al.,23 55.3% of users preferred telephone assistance over in-person consultations. We hypothesise that greater levels of satisfaction among non-coetaneous carers may be explained by the fact that these carers are more familiar with telephone communication than coetaneous carers; the same conclusion was also reached by the authors of a study conducted in Alicante.15 One of the main factors explaining the high degree of satisfaction of carers in our study is the fact that the neurologist calling carers had assessed the patient at least once previously, whereas in other studies, physicians providing telephone assistance had never assessed the patients in person.24

TAS provide more personalised assistance and are available on demand; furthermore, they improve follow-up of patients’ clinical alterations and reduce caregiving burden, which frequently develop over the course of the disease. On-demand telephone assistance is less intrusive than “proactive” telephone support.17 Our results may be extrapolated to other populations with similar sociocultural characteristics.25 In the light of these findings, we feel that TAS should be included among the services offered by dementia units. In the future, TAS will probably form part of a multicomponent programme including more frequent “proactive” interventions8 aimed at improving users’ quality of life and reducing healthcare costs.

FundingThe authors have received no funding of any kind for this research study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Garzón-Maldonado FJ, Gutiérrez-Bedmar M, Serrano-Castro V, Requena-Toro MV, Padilla-Romero L, García-Casares N. Evaluación de la asistencia telefónica a demanda en cuidadores de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Neurología. 2017;32:595–601.