The Spanish Health System's stroke care strategy (EISNS) is a consensus statement that was drawn up by various government bodies and scientific societies with the aim of improving quality throughout the care process and ensuring equality among regions. Our objective is to analyse existing healthcare resources and establish whether they have met EISNS targets.

Material and methodsThe survey on available resources was conducted by a committee of neurologists representing each of Spain's regions; the same committee also conducted the survey of 2008. The items included were the number of stroke units (SU), their resources (monitoring, neurologists on call 24 hours/7 days, nurse ratio, protocols), SU bed ratio/100000 inhabitants, diagnostic resources (cardiac and cerebral arterial ultrasound, advanced neuroimaging), performing intravenous thrombolysis, neurovascular interventional radiology (neuro VIR), surgery for malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarctions and telemedicine availability.

ResultsWe included data from 136 hospitals and found 45 Stroke Units distributed unequally among regions. The ratio of SU beds to residents ranged from 1/74000 to 1/1037000 inhabitants; only the regions of Cantabria and Navarre met the target. Neurologists performed 3237 intravenous thrombolysis procedures in 83 hospitals; thrombolysis procedures compared to the total of ischaemic strokes yielded percentages ranging from 0.3% to 33.7%. Hospitals without SUs showed varying levels of available resources. Neuro VIR is performed in every region except La Rioja, and VIR is only available on a 24 hours/7 days basis in 17 cities. Surgery for malignant MCA infarction is performed in 46 hospitals, and 5 have telemedicine.

ConclusionStroke care has improved in terms of numbers of participating hospitals, the increased use of intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular procedures, and surgery for malignant MCA infarction. Implementation of SUs and telemedicine remain insufficient. The availability of diagnostic resources is good in most SUs and irregular in other hospitals. Regional governments should strive to ensure better care and territorial equality, which would achieve the EISNS objectives.

La Estrategia del Ictus del Sistema Nacional de Salud (EISNS) fue un documento de consenso entre las distintas administraciones y sociedades científicas que se desarrolló con el objetivo de mejorar la calidad del proceso asistencial y garantizar la equidad territorial. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar los recursos asistenciales existentes y si se había cumplido el objetivo de la EISNS.

Material y métodosLa encuesta sobre los recursos disponibles se realizó por un comité de neurólogos de cada una de las comunidades autónomas (CC.AA), los cuales también realizaron la encuesta de 2008. Los ítems incluidos fueron el número de Unidades de Ictus (UI), su dotación (monitorización, neurólogo 24h/7 días, ratio enfermería, protocolos), ratio cama UI/100.000 habitantes, recursos diagnósticos (ecografía cardíaca y arterial cerebral, neuroimagen avanzada), realización de trombolisis intravenosa, intervencionismo neurovascular (INV), cirugía del infarto maligno de la arteria cerebral media (ACM) y disponibilidad de la telemedicina.

ResultadosSe incluyeron datos de 136 hospitales. Existen 45 UI distribuidas de un modo desigual. La relación cama de UI por habitantes y comunidad autónoma osciló entre 1/74.000 a 1/1.037.000 habitantes, cumpliendo el objetivo solo Cantabria y Navarra. Se realizaron por neurólogos 3.237 trombolisis intravenosas en 83 hospitales, con un porcentaje respecto del total de ictus isquémico entre el 0,3 y el 33,7%. Los hospitales sin UI tenían una disponibilidad variable de recursos. Se realiza INV en todas las CC.AA salvo La Rioja, la disponibilidad del INV 24h/7 días solo existe en 17 ciudades. Hay 46 centros con cirugía del infarto maligno de la ACM y 5 con telemedicina.

ConclusiónLa asistencia al ictus ha mejorado en cuanto al incremento de hospitales participantes, la mayor aplicación de trombolisis intravenosa y procedimientos endovasculares, también en la cirugía del infarto maligno de la ACM, pero con insuficiente implantación de UI y de la telemedicina. La disponibilidad de recursos diagnósticos es buena en la mayoría de las UI, e irregular en el resto de hospitales. Las distintas CC.AA deben avanzar para garantizar el mejor tratamiento y equidad territorial, y así conseguir el objetivo de la EISNS.

Stroke is a complex and heterogeneous entity that includes both ischaemic and haemorrhagic cerebrovascular disease. From an aetiological point of view, stroke is mainly associated with traditional vascular risk factors. It is also often associated with other manifestations of atherosclerotic vascular disease, such as ischaemic heart disease or peripheral artery disease. Stroke is currently an important cause of dependency and death1,2 and it also generates considerable costs for patients, families, and societies.3

The quality of stroke care has improved greatly following the establishment of stroke units (SU). Stroke units act as intermediate care units during the acute phase and constitute a cost-effective measure since they reduce mortality, neurological sequelae, and the need for institutional care.4,5 This beneficial effect of SUs is independent from such factors as age, sex, aetiological subtype, or stroke severity.4 Intravenous thrombolysis is the second treatment measure shown to be effective in improving functional outcome of patients.6–8 This technique requires neurologists trained in acute stroke care if it is to be employed safely and prescribed correctly.9–11 In those patients who have not undergone intravenous thrombolysis or those for whom the technique is contraindicated, endovascular techniques (neurovascular interventions [Neuro VIR]) such as intra-arterial thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy can be applied.12

Advanced neuroimaging studies with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allow doctors to assess the brain tissue at risk. This is useful when deciding whether to apply thrombolytic treatment in cases of wake-up stroke, or whether to extend the therapeutic window.8,13 Telemedicine is a resource that lets doctors remotely evaluate patients, thereby promoting access to thrombolysis for patients whose treatment options are geographically limited.14,15 Telemedicine can be used to evaluate not only the patient's clinical examination, but also findings from radiology studies performed in hospital facilities. Another intervention which has proved to be effective in stroke management is the use of decompressive craniectomy for treating malignant infarct of the medial cerebral artery. The surgical procedure decreases the high mortality and disability rates associated with this entity.16

The Spanish Society of Neurology's Study Group for Cerebrovascular Diseases (GEECV) has issued a series of recommendations for a coordinated care system for acute stroke.17–19 The stroke healthcare plan (PASI) and its revised version also established care levels for stroke according to available care resources, dividing hospitals into 3 levels.19 The classification includes hospitals with stroke teams, hospitals with SUs, and stroke centres of reference.19,20

In 2008, the Inter-regional Council of the Ministry of Health and Social Policy approved the Spanish Health System's stroke care strategy (EISNS).21 The EISNS was a consensus statement by scientific and professional societies on stroke and representatives from the 17 Spanish regions and the National Institute of Healthcare Management (INGESA). This statement addresses many stroke-related topics, such as prevention, care during the acute phase, rehabilitation, and research. It establishes that every Spanish region must draft a regional stroke plan that will list the resources needed to meet the plan's objectives.

Across Europe, few patients with stroke are admitted to stroke units despite the available evidence attesting to the positive effects of SU care. This situation is contrary to the Helsingborg Declaration recommendations. The EISNS has tried to increase the number of stroke units by redirecting the appropriate care resources.21–23 Our study is aimed at assessing the resources available for acute stroke care in 2012 and comparing them with the results of the survey carried out in 2008 in locations in which EISNS had been implemented.24

Material and methodsA national survey was conducted between January and June 2012 in every region of Spain with the exception of the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla. The survey was coordinated by 2 representatives from each region, all of whom were GEECV members who had not participated in drafting the EISNS. These representatives transmitted the questionnaire to the coordinators of the SU or neurology department at each hospital. The questionnaire included the same items that had been analysed in the survey on available resources in 2008. Data were collected from 136 Spanish public hospitals listed in the National Catalogue of Spanish Hospitals. Private hospitals providing care to patients not registered with the National Healthcare Service were not included.

Researchers gathered data on SU availability in each hospital and the total number of beds per SU. We also calculated the SU-to-population and SU bed-to-population ratios based on the number of inhabitants of each region. The number of SUs per region and the provinces with no available SUs were also recorded. In order to determine whether SUs had the minimum equipment necessary to provide adequate stroke care, we checked if they included an on-site neurologist 24 hours a day 7 days a week, non-invasive multi-parameter monitoring (MPM), trained nursing staff with a nurse/SU bed ratio of 1:4 to 1:6, and their own diagnostic and therapeutic protocols.

Another item assessed was the number of hospitals with intravenous thrombolysis performed by neurologists, and the number of patients treated in each centre and in each community during 2011. We also assessed the percentage of patients treated compared with the total patients admitted due to ischaemic stroke. We recorded the number of centres with experience performing Neuro VIR and the schedule during which endovascular treatment was available. Data on the availability of advanced neuroimaging techniques during the acute phase of stroke were also gathered. We recorded whether CT, MRI or both techniques were available. Additionally, we recorded the number of hospitals with protocols for decompressive craniectomy for treating malignant infarct of the middle cerebral artery territory. Lastly, we documented any telemedicine programmes for treating acute stroke and measured the populations without access to this service and residing in an area without an SU.

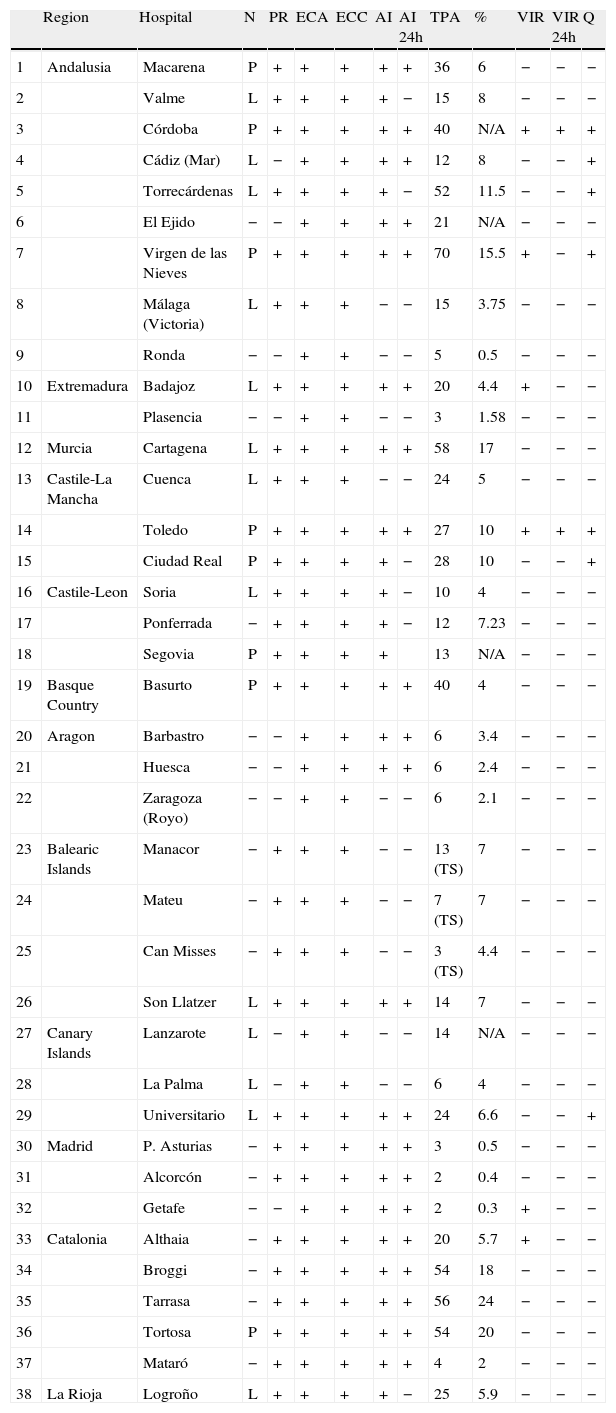

ResultsWe collected data from 136 Spanish hospitals; 45 hospitals in Spain have SUs. With only 3 exceptions, all SUs have a neurologist working 24 hours a day and 365 days a year, which is an essential resource. The requirement of having nursing staff trained in stroke care present at a ratio of one nurse per 4 to 6 beds is met by all SUs except for 4 (in these cases, staff is shared with the rest of the ward). The other 2 requirements (protocols and MPM) were met by 44 SUs. Having care protocols is also important for hospitals with no SUs, as is the case of 28 out of the 38 hospitals (Table 1). Of the 38 hospitals in which neurologists administer thrombolysis, 8 have an on-site neurologist and 13 have a neurologist on call.

Diagnostic procedures and treatments in hospitals with no SUs providing treatment with rt-PA in 2011.

| Region | Hospital | N | PR | ECA | ECC | AI | AI 24h | TPA | % | VIR | VIR 24h | Q | |

| 1 | Andalusia | Macarena | P | + | + | + | + | + | 36 | 6 | − | − | − |

| 2 | Valme | L | + | + | + | + | − | 15 | 8 | − | − | − | |

| 3 | Córdoba | P | + | + | + | + | + | 40 | N/A | + | + | + | |

| 4 | Cádiz (Mar) | L | − | + | + | + | + | 12 | 8 | − | − | + | |

| 5 | Torrecárdenas | L | + | + | + | + | − | 52 | 11.5 | − | − | + | |

| 6 | El Ejido | − | − | + | + | + | + | 21 | N/A | − | − | − | |

| 7 | Virgen de las Nieves | P | + | + | + | + | + | 70 | 15.5 | + | − | + | |

| 8 | Málaga (Victoria) | L | + | + | + | − | − | 15 | 3.75 | − | − | − | |

| 9 | Ronda | − | − | + | + | − | − | 5 | 0.5 | − | − | − | |

| 10 | Extremadura | Badajoz | L | + | + | + | + | + | 20 | 4.4 | + | − | − |

| 11 | Plasencia | − | − | + | + | − | − | 3 | 1.58 | − | − | − | |

| 12 | Murcia | Cartagena | L | + | + | + | + | + | 58 | 17 | − | − | − |

| 13 | Castile-La Mancha | Cuenca | L | + | + | + | − | − | 24 | 5 | − | − | − |

| 14 | Toledo | P | + | + | + | + | + | 27 | 10 | + | + | + | |

| 15 | Ciudad Real | P | + | + | + | + | − | 28 | 10 | − | − | + | |

| 16 | Castile-Leon | Soria | L | + | + | + | + | − | 10 | 4 | − | − | − |

| 17 | Ponferrada | − | + | + | + | + | − | 12 | 7.23 | − | − | − | |

| 18 | Segovia | P | + | + | + | + | 13 | N/A | − | − | − | ||

| 19 | Basque Country | Basurto | P | + | + | + | + | + | 40 | 4 | − | − | − |

| 20 | Aragon | Barbastro | − | − | + | + | + | + | 6 | 3.4 | − | − | − |

| 21 | Huesca | − | − | + | + | + | + | 6 | 2.4 | − | − | − | |

| 22 | Zaragoza (Royo) | − | − | + | + | − | − | 6 | 2.1 | − | − | − | |

| 23 | Balearic Islands | Manacor | − | + | + | + | − | − | 13 (TS) | 7 | − | − | − |

| 24 | Mateu | − | + | + | + | − | − | 7 (TS) | 7 | − | − | − | |

| 25 | Can Misses | − | + | + | + | − | − | 3 (TS) | 4.4 | − | − | − | |

| 26 | Son Llatzer | L | + | + | + | + | + | 14 | 7 | − | − | − | |

| 27 | Canary Islands | Lanzarote | L | − | + | + | − | − | 14 | N/A | − | − | − |

| 28 | La Palma | L | − | + | + | − | − | 6 | 4 | − | − | − | |

| 29 | Universitario | L | + | + | + | + | + | 24 | 6.6 | − | − | + | |

| 30 | Madrid | P. Asturias | − | + | + | + | + | + | 3 | 0.5 | − | − | − |

| 31 | Alcorcón | − | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | 0.4 | − | − | − | |

| 32 | Getafe | − | − | + | + | + | + | 2 | 0.3 | + | − | − | |

| 33 | Catalonia | Althaia | − | + | + | + | + | + | 20 | 5.7 | + | − | − |

| 34 | Broggi | − | + | + | + | + | + | 54 | 18 | − | − | − | |

| 35 | Tarrasa | − | + | + | + | + | + | 56 | 24 | − | − | − | |

| 36 | Tortosa | P | + | + | + | + | + | 54 | 20 | − | − | − | |

| 37 | Mataró | − | + | + | + | + | + | 4 | 2 | − | − | − | |

| 38 | La Rioja | Logroño | L | + | + | + | + | − | 25 | 5.9 | − | − | − |

DCT: transcranial duplex and carotid ultrasound; ECC: transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiogram; AI: advanced imaging study; AI 24: advanced imaging study at 24 hours; L: localised; N: on-call neurology department; N/A: not available; P: full time; PR: protocols; Q: surgery for malignant infarct of the medial cerebral artery; VIR: neurointerventional radiology; VIR 24: neurointerventional radiology at 24 hours; TS: telestroke; TPA: no. of intravenous thrombolysis treatments; %: percent treated out of total admissions.

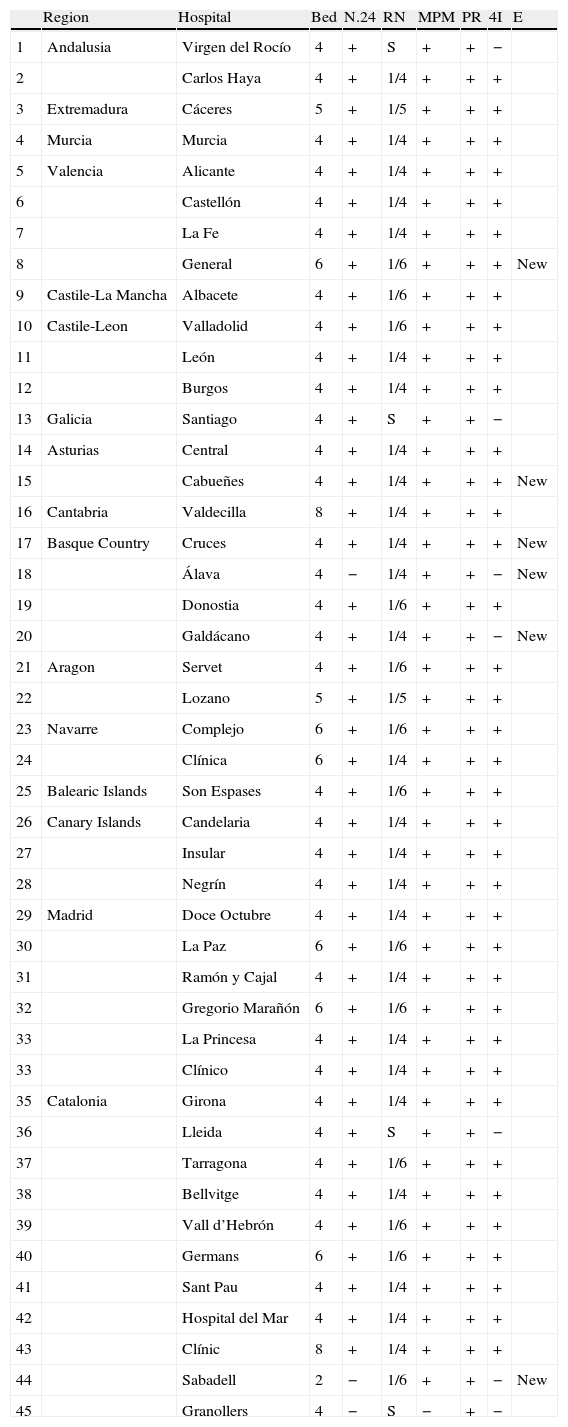

The SUs that have been implemented in Spain are unevenly distributed. They are present in most regions (94%) but only 48% of Spain's capital cities have these units (Table 2). There are no SUs in 22 provinces, of which 16 have a population of more than 300000 inhabitants, which would call for at least 3 SU beds in each one. However, a significant number of centres with no SUs do have all the recommended diagnostic and therapeutic resources (Table 1). The lack of SUs is especially striking in Andalusia, with only one SU in 2 of its 8 provinces; Galicia with only one, and La Rioja with no SUs. Analysis of the SU bed-to-inhabitant ratio in each region shows that only Cantabria and Navarra meet the target of having at least 1 SU bed per 100000 inhabitants. As reported by the previous survey, the least equipped regions are Andalusia (1 SU bed per million inhabitants), and La Rioja (no SU beds).

List of SUs and available resources in 2011.

| Region | Hospital | Bed | N.24 | RN | MPM | PR | 4I | E | |

| 1 | Andalusia | Virgen del Rocío | 4 | + | S | + | + | − | |

| 2 | Carlos Haya | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 3 | Extremadura | Cáceres | 5 | + | 1/5 | + | + | + | |

| 4 | Murcia | Murcia | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 5 | Valencia | Alicante | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 6 | Castellón | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 7 | La Fe | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 8 | General | 6 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | New | |

| 9 | Castile-La Mancha | Albacete | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | |

| 10 | Castile-Leon | Valladolid | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | |

| 11 | León | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 12 | Burgos | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 13 | Galicia | Santiago | 4 | + | S | + | + | − | |

| 14 | Asturias | Central | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 15 | Cabueñes | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | New | |

| 16 | Cantabria | Valdecilla | 8 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 17 | Basque Country | Cruces | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | New |

| 18 | Álava | 4 | − | 1/4 | + | + | − | New | |

| 19 | Donostia | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 20 | Galdácano | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | − | New | |

| 21 | Aragon | Servet | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | |

| 22 | Lozano | 5 | + | 1/5 | + | + | + | ||

| 23 | Navarre | Complejo | 6 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | |

| 24 | Clínica | 6 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 25 | Balearic Islands | Son Espases | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | |

| 26 | Canary Islands | Candelaria | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 27 | Insular | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 28 | Negrín | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 29 | Madrid | Doce Octubre | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 30 | La Paz | 6 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 31 | Ramón y Cajal | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 32 | Gregorio Marañón | 6 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 33 | La Princesa | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 33 | Clínico | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 35 | Catalonia | Girona | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | |

| 36 | Lleida | 4 | + | S | + | + | − | ||

| 37 | Tarragona | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 38 | Bellvitge | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 39 | Vall d’Hebrón | 4 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 40 | Germans | 6 | + | 1/6 | + | + | + | ||

| 41 | Sant Pau | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 42 | Hospital del Mar | 4 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 43 | Clínic | 8 | + | 1/4 | + | + | + | ||

| 44 | Sabadell | 2 | − | 1/6 | + | + | − | New | |

| 45 | Granollers | 4 | − | S | − | + | − |

S: shared; A: advancement; MPM: monitoring; N.24: neurologist working 24 hours; PR: protocol; RN: ratio nurse/bed; NC: no changes; 4 I: presents 4 items.

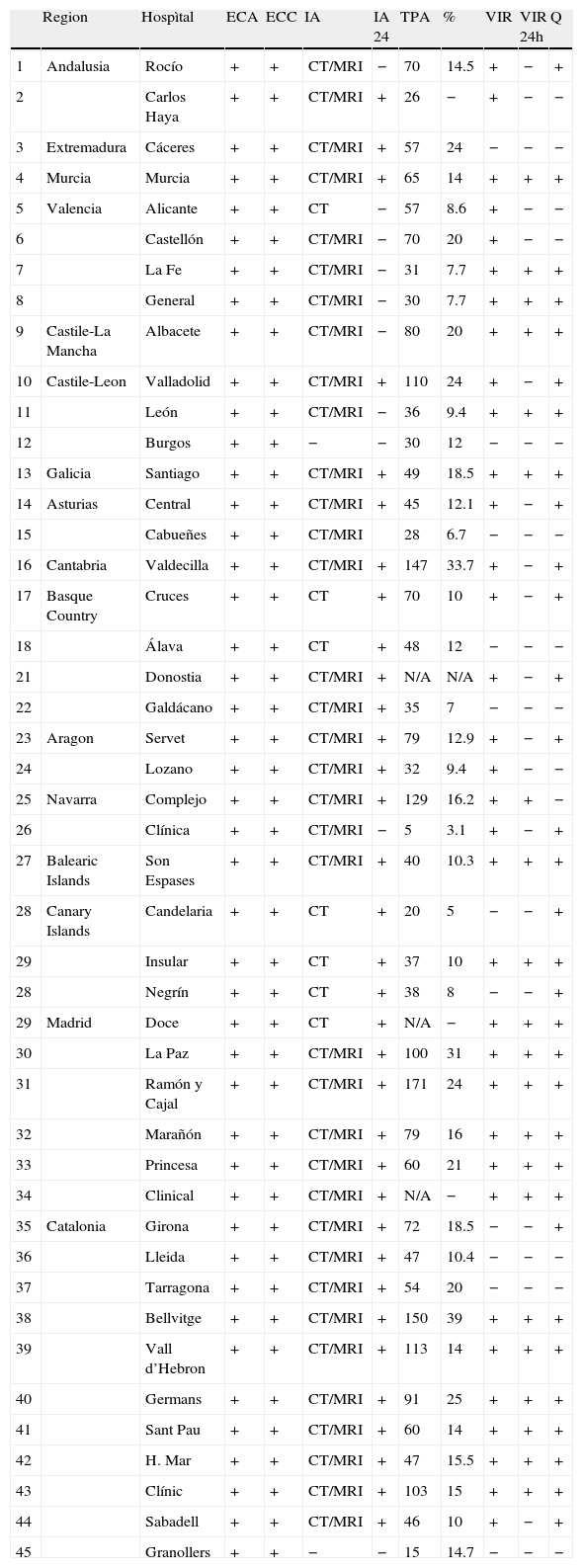

SUs are equipped with the necessary diagnostic resources for studying stroke. All of them are able to perform intra- and extracranial artery studies as well as ultrasonography and angiography studies using conventional arteriography, CT, or MRI. All hospitals with SUs have access to advanced neuroimaging techniques for artery evaluation and ischaemic penumbra imaging, whereas all hospitals providing stroke treatment have access to one of the above techniques and 29 of them have access to both (Table 3). However, 24 centres that perform thrombolysis during the acute phase only have access to CT techniques. All hospitals with SUs are equipped to carry out cardiac studies, including transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography. These resources are also available in the remaining hospitals in which intravenous thrombolysis is performed, and 27 of these hospitals also make use of advanced neuroimaging techniques (Table 1).

Diagnostic procedures and treatments available in SUs in 2011.

| Region | Hospìtal | ECA | ECC | IA | IA 24 | TPA | % | VIR | VIR 24h | Q | |

| 1 | Andalusia | Rocío | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 70 | 14.5 | + | − | + |

| 2 | Carlos Haya | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 26 | − | + | − | − | |

| 3 | Extremadura | Cáceres | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 57 | 24 | − | − | − |

| 4 | Murcia | Murcia | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 65 | 14 | + | + | + |

| 5 | Valencia | Alicante | + | + | CT | − | 57 | 8.6 | + | − | − |

| 6 | Castellón | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 70 | 20 | + | − | − | |

| 7 | La Fe | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 31 | 7.7 | + | + | + | |

| 8 | General | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 30 | 7.7 | + | + | + | |

| 9 | Castile-La Mancha | Albacete | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 80 | 20 | + | + | + |

| 10 | Castile-Leon | Valladolid | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 110 | 24 | + | − | + |

| 11 | León | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 36 | 9.4 | + | + | + | |

| 12 | Burgos | + | + | − | − | 30 | 12 | − | − | − | |

| 13 | Galicia | Santiago | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 49 | 18.5 | + | + | + |

| 14 | Asturias | Central | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 45 | 12.1 | + | − | + |

| 15 | Cabueñes | + | + | CT/MRI | 28 | 6.7 | − | − | − | ||

| 16 | Cantabria | Valdecilla | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 147 | 33.7 | + | − | + |

| 17 | Basque Country | Cruces | + | + | CT | + | 70 | 10 | + | − | + |

| 18 | Álava | + | + | CT | + | 48 | 12 | − | − | − | |

| 21 | Donostia | + | + | CT/MRI | + | N/A | N/A | + | − | + | |

| 22 | Galdácano | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 35 | 7 | − | − | − | |

| 23 | Aragon | Servet | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 79 | 12.9 | + | − | + |

| 24 | Lozano | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 32 | 9.4 | + | − | − | |

| 25 | Navarra | Complejo | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 129 | 16.2 | + | + | − |

| 26 | Clínica | + | + | CT/MRI | − | 5 | 3.1 | + | − | + | |

| 27 | Balearic Islands | Son Espases | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 40 | 10.3 | + | + | + |

| 28 | Canary Islands | Candelaria | + | + | CT | + | 20 | 5 | − | − | + |

| 29 | Insular | + | + | CT | + | 37 | 10 | + | + | + | |

| 28 | Negrín | + | + | CT | + | 38 | 8 | − | − | + | |

| 29 | Madrid | Doce | + | + | CT | + | N/A | − | + | + | + |

| 30 | La Paz | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 100 | 31 | + | + | + | |

| 31 | Ramón y Cajal | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 171 | 24 | + | + | + | |

| 32 | Marañón | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 79 | 16 | + | + | + | |

| 33 | Princesa | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 60 | 21 | + | + | + | |

| 34 | Clinical | + | + | CT/MRI | + | N/A | − | + | + | + | |

| 35 | Catalonia | Girona | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 72 | 18.5 | − | − | + |

| 36 | Lleida | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 47 | 10.4 | − | − | − | |

| 37 | Tarragona | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 54 | 20 | − | − | − | |

| 38 | Bellvitge | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 150 | 39 | + | + | + | |

| 39 | Vall d’Hebron | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 113 | 14 | + | + | + | |

| 40 | Germans | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 91 | 25 | + | + | + | |

| 41 | Sant Pau | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 60 | 14 | + | + | + | |

| 42 | H. Mar | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 47 | 15.5 | + | + | + | |

| 43 | Clínic | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 103 | 15 | + | + | + | |

| 44 | Sabadell | + | + | CT/MRI | + | 46 | 10 | + | − | + | |

| 45 | Granollers | + | + | − | − | 15 | 14.7 | − | − | − |

TDC: transcranial Doppler and carotid ultrasound; ECC: transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiogram; N/A: not available; Q: surgery for malignant infarct of the medial cerebral artery; VIR: neurointerventional radiology; VIR 24: neurointerventional radiology 24 hours; TS: telestroke; TPA: no. intravenous thrombolysis treatments; %: percent treated out of total admissions.

Intravenous thrombolysis programmes coordinated by neurologists have been implemented in 83 hospitals distributed among all regions. On-site neurologists are available 24 hours a day in 61 hospitals. Seven of these hospitals treat fewer than 5 patients per year, which is an improvement on results from the previous survey showing that 12.5% of the 80 hospitals treated fewer than 5 stroke patients yearly. Although figures for intravenous thrombolysis depend on the centre administering the treatment, we have observed a significant increase in the number of treated patients, who now account for 39% of the total patients admitted due to ischaemic stroke. The total number of cases treated with thrombolysis in Spain comes to 2345. Hospitals without SUs treat fewer cases, and 20 SUs and 15 centres with no SUs treat more than 5% of all stroke cases (Tables 1 and 3). The increase in the number of treatments has been homogeneous across the country and has even affected hospitals lacking an SU. These hospitals administer treatment to a percentage that ranges from 0.3% to 24% of the patient total (Table 1). The highest percentages of patients treated with thrombolysis can be found in large hospitals in Madrid and Barcelona.

Interventional radiology for treating acute stroke is available in all autonomous communities except for La Rioja. Nevertheless, only 42 hospitals have access to this resource; 33 of them are hospitals with an SU that provide care to a total of 27 provinces (Tables 1 and 3). This also amounts to an increase compared to the previous situation, as interventional radiology is now available 24 hours a day and 365 days a year in 17 different healthcare areas. It should be noted that care demand is satisfied by a node network system in Catalonia and Madrid. Surgery for treating malignant infarct of the middle cerebral artery is available in 37 of the 45 centres that have an SU (Table 3) and in 9 centres that do not have an SU (Table 1).

In 2009, telemedicine was only available in the Balearic Islands but we observe that the situation has improved since then, and that telemedicine is now available in 5 geographical areas.

DiscussionEISNS was promoted by the Ministry of Health and Social Policy and created by the consensus of all scientific societies involved in stroke care. All of Spain's regional governments then ratified the strategy.21 By this process, each of Spain's different autonomous communities was entrusted with drafting its own regional plan and determining what resources would be necessary to meet EISNS targets within a time frame of 2 years. The aim was to introduce improvements that would optimise the care process according to scientific evidence, thereby guaranteeing equal access to care throughout Spain. Data from the time when the EISNS was ratified showed unequal access to healthcare, meaning that available infrastructure was optimal in some regions and deficient in others. The purpose of the GEECV's first survey on stroke care resources in Spain was to ascertain the true situation of neurological care for acute stroke at the end of 2008. Data collection was to be repeated 2 years later to evaluate whether acute stroke care had improved once the EISNS had already been implemented.24 The scope of this survey did not include an analysis of other wider-reaching goals of EISNS. These goals included such important points as primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease, rehabilitation therapy, and social integration, as well as improving research and training in the field of cerebrovascular disease.

Stroke units represent the best treatment option for stroke and offer the most benefits to the stroke patient population.25–27 Stroke units reduce probability of death or disability in all patient subgroups, except in patients with reduced level of consciousness. This benefit remains evident over the long term.25,26 Early neurological monitoring and evaluation, together with multidisciplinary management, are associated with lower mortality and dependency rates after stroke.28,29 A 2009 survey found that SU resources were sufficient based on an analysis of the nursing staff ratio, monitoring, continuous care, and use of action protocols.24 However, these resources were unevenly distributed and largely concentrated in such major cities as Madrid and Barcelona. The target of having at least one SU bed per 100000 inhabitants was not met.24 Territorial inequalities were apparent and resources were clearly insufficient in Andalusia, Galicia, Castile-La Mancha and La Rioja. However, a significant number of hospitals that lack SUs do have access to key resources for stroke diagnosis and treatment. In this area, Spain is no different from other countries in the European Union that display the same gaps in SU availability.30 We should highlight the significance of this initiative by the Ministry of Health and Social Policy which aims to increase the array of available resources. No similar initiatives have been launched in our neighbouring countries.

Current data show an increase in the total number of SUs, but Spain's SUs remain insufficient to satisfy care demands at an optimal level. Three SUs have been set up in Catalonia and the Basque Country, one in Asturias, and another in the Region of Valencia. We can therefore state that the territorial inequalities documented by the previous survey persist, given that there have been no improvements in regions with reduced resources. The regions with the least resources are Andalusia and La Rioja, but Castile-La Mancha and Galicia are also poorly equipped. There were no increases in the ratio of SU beds to inhabitants, and the target of one SU bed per 100000 inhabitants has only been met in Cantabria. There are no SUs in 22 provinces, a situation which limits ten million people's access to specialised stroke care. Sixteen Spanish provinces have populations of more than 300000 inhabitants, which indicates that each one needs at least 3 SU beds.

All SUs meet targets having to do with multi-parameter monitoring, following diagnostic and therapeutic protocols, and implementing a multidisciplinary work scheme. Forty-one of the 44 SUs are staffed with on-site neurologists 24 hours a day, a resource that we consider essential. The presence of a neurologist providing continuous care to stroke patients has been associated with improved quality of stroke care due to better early evaluation and treatment access, which improves patient prognosis.31,32 Nursing staff numbers are sufficient according to the recommendations. The ratio of 1 nurse per 4 to 6 beds is not met in only 5 SUs, a situation which should be remedied immediately.

Availability of diagnostic resources in stroke care systems is crucial for determining the aetiological diagnosis and also for acute phase management that makes use of advanced neuroimaging techniques.19,33,34 These techniques improve the patient selection procedure and have led to improvements in the implementation of new treatments and indications.8 SUs are equipped with the necessary diagnostic resources for studying stroke. All of them are able to perform intra- and extracranial artery studies and they can also conduct ultrasonography and angiography studies using conventional arteriography, CT, or MRI. All hospitals with SUs have access to advanced neuroimaging techniques for artery evaluation and ischaemic penumbra imaging, all hospitals providing stroke treatment have access to one of these techniques, and 29 of these centres have access to both. However, 24 hospitals that perform thrombolysis during the acute phase only have access to CT techniques. Furthermore, all SUs have transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography equipment that lets doctors perform cardiac studies.

Intravenous thrombolysis has proved to be the most effective treatment for acute cerebral infarct.6,7 Implementation of ‘code stroke’ was necessary in order to promote intravenous thrombolysis, which was one of the objectives of the EISNS. SUs provide benefits to the vast majority of stroke patients. In contrast, the narrow therapeutic window combined with the multiple complications of stroke result in intravenous thrombolysis being used in 10% to 15% of all cases of cerebral infarct in a best-case scenario; the usual rates are 3% to 5%.10,35,36 In our survey, we gathered data from 82 centres in which this treatment is administered by neurologists. There are only 45 SUs in Spain and this small number means that Spanish neurologists have implemented thrombolysis programmes in many centres that lack an SU. This treatment is safe when performed by trained neurologists according to an established protocol, even when the hospital has no SU.37,38 It is a known fact that the percentage of thrombolysis-related complications is higher in centres performing fewer than 5 treatments yearly.10 This is the case in only 7 of the 82 centres in which neurologists administer this treatment. We identified a surprisingly large increase (39%) in thrombolysis treatments compared to total patients admitted with ischaemic stroke. This could be partly due to doctors’ growing experience with the technique and to having extended the therapeutic window to 4.5 hours after stroke onset. Additionally, increased experience with this technique means that it can be safely used for certain restricted indications that were not contemplated by initial clinical studies or listed in the drug leaflet for tissue plasminogen activator.39,40 Higher treatment rates are mainly to be found in Madrid and Barcelona, although the rate also exceeded 30% in Cantabria. The number of treatments provided varies considerably between different regions and we have even observed anecdotal cases of hospitals with rates as low as 0.5%. This situation can be explained in part by the number of SU beds in each region, although this is not the only cause. We all should increase our efforts to maximise the number of patients treated with t-PA. This goal is beginning to be achieved as we can see from the marked increase in the percentage of patients receiving treatment. Hospitals and stroke units with lower numbers of treatments per year should identify the problematic link in the healthcare chain (recognition of stroke symptoms by the population, extrahospital or in-hospital code stroke, or response times and decision-making by the on-call neurology team).

Neuro VIR was not included among the EISNS targets since it was in early stages of development at the time and little scientific evidence on its use in acute stroke was available. However, it has been included among the objectives of the updated version of PASI. Neuro VIR is a feasible alternative to intravenous thrombolysis when the latter is not indicated or has not been effective. Different techniques (mechanical thrombectomy, intra-arterial thrombolysis, and angioplasty), each of which has its corresponding indications and therapeutic window, have proved their benefit in treating acute-phase stroke.41–45 The analysis of this survey shows that VIR is available in all regions except for La Rioja. Centres have the technical ability and experience necessary to perform the procedure. Although patients can only be treated during morning shifts at many centres, this situation has improved substantially since 2009. Previously, only 2 hospitals were able to perform VIR 24 hours a day, but treatment is now available in 17 geographic areas. In Madrid and Catalonia, the system is structured around central nodes in order to ensure the most efficient use of resources while also making management sustainable over time. It is not acceptable for our patients’ access to treatment to be determined by the time of day during which they suffer strokes, and therefore we must redouble our efforts to offer treatment to the entire Spanish population. To this end, we must find management solutions that will allow us to adjust the technical resources available in every geographical area.

The possibility of recanalisation is limited for patients who live far from specialised centres and only have access to local hospitals staffed by doctors who are not neurologists and lack experience with this procedure. Furthermore, not all hospitals should provide care to stroke patients, as has been observed by studies carried out in different countries.10 Telemedicine is an alternative that facilitates early access to thrombolysis. It doubles the number of stroke patients receiving specialised emergency neurological care, in addition to the number of fibrinolytic treatments; it also significantly reduces time elapsed until starting thrombolysis to 50 minutes. It can also increase the number of patients treated in the 0 to 3-hour window and reduces the number of inter-hospital transfers by more than a third.46,47 Spanish telemedicine resources are insufficiently developed, even though Spain includes many islands and other locations more than 60 minutes away from the centre of reference; 60 minutes is the maximum recommended time for patient transport.13 Telemedicine was initially implemented in the Balearic Islands, and subsequently in Barcelona and Seville. Results were good in terms of safety and efficacy.48 By 2011, one centre in Madrid and another in Galicia had joined the 3 centres mentioned above. A total of 5 reference hospitals were thus able to overcome the geographical barriers to thrombolytic treatment. Nevertheless, a significant segment of the population still lacks access to this treatment, whether due to lack of infrastructure or to living more than an hour from the closest hospital with an SU, given that 60 minutes is the recommended time limit for administering thrombolysis.

ConclusionThe aim of this survey was to analyse the stroke care resources available at a national level, their distribution, and any improvements recorded after the EISNS was formalised and implemented. Although the situation has improved compared to the data from the 2008 survey, we were able to demonstrate that SU implementation in Spain remains insufficient. We have also concluded that territorial inequalities persist, given that SUs are concentrated in larger cities and promoting these units is a secondary priority in some regions. Although there has been a considerable increase in cases receiving intravenous or endovascular treatments, there are still too few patients treated, which is another sign of lack of equality. The availability of diagnostic resources is adequate in most centres and all SUs meet the necessary requirements. Until now, telemedicine, a resource able to lessen geographical inequalities, has barely been promoted. It is therefore necessary that healthcare professionals continue to strive to meet the EISNS targets.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: López Fernández JC, Masjuan Vallejo J, Arenillas Lara J, Blanco González M, Botia Paniagua E, Casado Naranjo I, et al. Análisis de recursos asistenciales para el ictus en España en 2012: ¿beneficios de la Estrategia del Ictus del Sistema Nacional de Salud? Neurología. 2014;29:387–396.

Part of this study was presented orally at the 64th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.