In 1937, Hulusi Behçet discovered the disease that bears his name (BD). While it is described as a triple-system complex of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and uveitis,1 it may also affect other organs.2 We present a case of neuro-Behçet disease (NB) which manifested as brainstem meningoencephalitis (BME).

The patient, a Moroccan male aged 28 with no relevant medical history, was examined due to progressive impairment of the right upper limb (RUL). On the day he was admitted, examination yielded normal results except for acneiform lesions on the face and tactile hypoaesthesia and hypoalgesia of the RUL. On the following day he experienced weakness rated 2/5 in that limb, followed by drowsiness, fever (38.4°C), and neck stiffness at 24 hours.

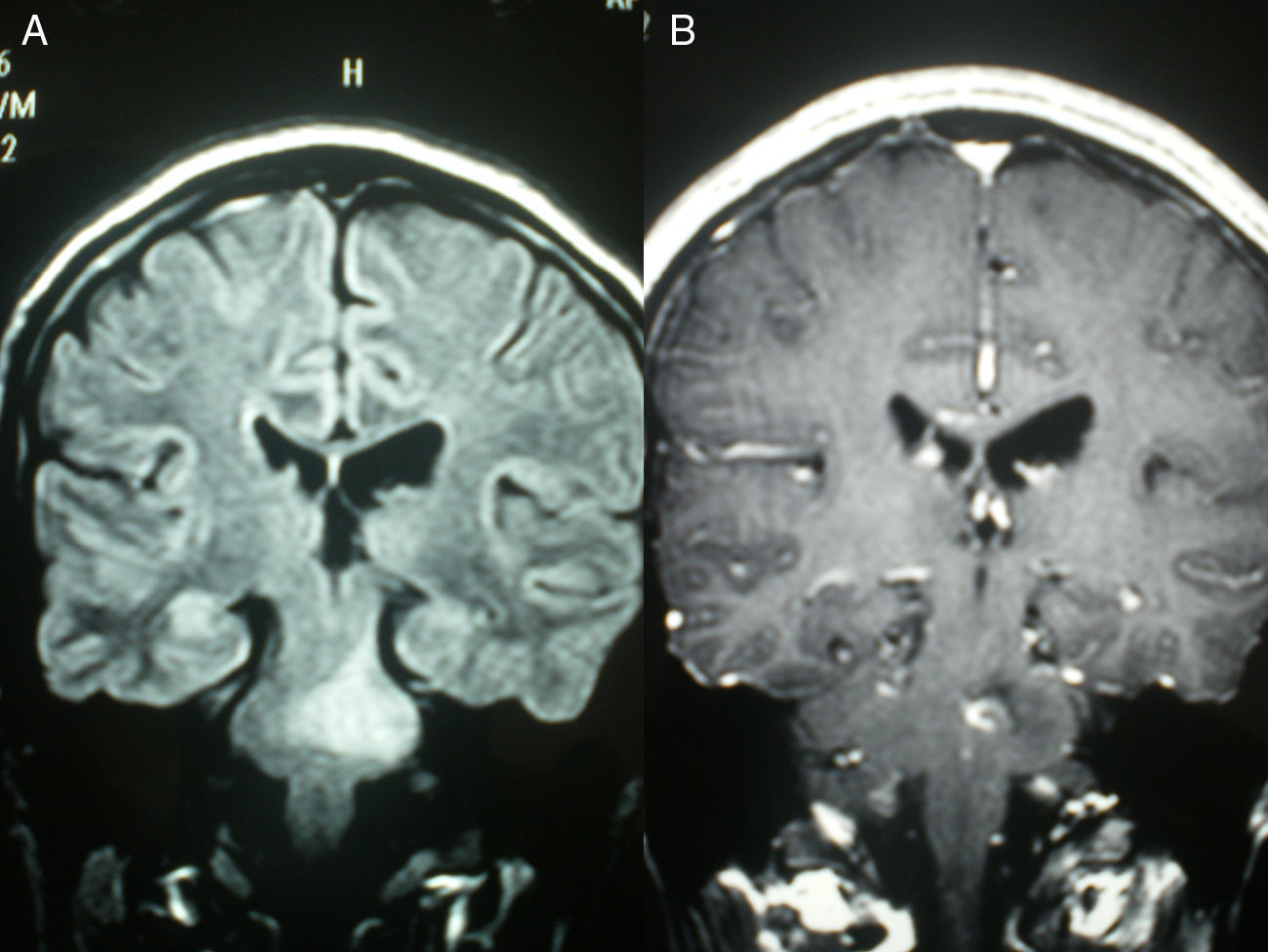

Laboratory analysis revealed leucocytosis (22000×103/μL) with neutrophilia, C reactive protein 15.02mg/dL (0–0.5), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 30mm/h during the first hour. Other blood count statistics were normal, as were coagulation values and a biochemistry study with thyroid, liver, and lipid profiles. Urine was negative for toxins and urine sediment was normal. Cranial computed tomography revealed non-specific left paramedian pontine hypodensity of ischaemic, inflammatory, or neoplastic origin. Lumbar puncture yielded turbid cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a glucose level of 57mg/dL (capillary blood glucose 104); proteins 142mg/dL (15–45), and 670 cells (80% granulocytes). Gram stain and culture were negative. Serology studies for herpes simplex virus (HSV), HIV, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, Borrelia, and Rickettsia were negative; blood cultures were also negative. Anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, and angiotensin-converting enzyme counts were normal. The initial head MRI (Fig. 1A) showed a non-specific brainstem lesion (possibly glioma, plaque of demyelination, encephalitis, or ischaemia). MRI was repeated 48 hours later with gadolinium contrast (Fig. 1B). The lesion had increased in size and its contrast enhancement was compatible with BME. The red nucleus was not affected.

The patient received treatment with dexamethasone 4mg/6 hours, ceftriaxone 1g/12 hours, and acyclovir 250mg/8 hours, all delivered intravenously. The patient's level of consciousness recovered and fever resolved 48 hours after starting treatment. When questioned, he responded that on several occasions in the past few years he had suffered painful aphthous ulcers in the mouth and on the genitals in addition to acneiform facial lesions. He had never consulted a doctor because symptoms were self-limiting. As BD was suspected, doctors discontinued antimicrobials and maintained steroids. The pathergy test was negative. An ophthalmological assessment ruled out uveitis, and the dermatology department reported that lesions appeared to be compatible with those seen in BD. A biopsy of the lesions yielded a non-specific inflammatory infiltrate without granulomas.

Clinical progress was favourable; the fever resolved and the patient was alert between 24 and 48 hours after starting corticosteroid treatment. He was discharged with prednisone 30mg/24 hours and omeprazole 20mg/24 hours. He suffered a new outbreak of mouth ulcers (treated with chloroquine 155mg/12 hours) and urogenital ulcers (treated with pentoxifylline 600mg/12 hours). MRI performed a month after steroid treatment showed slight pontine atrophy and gliosis.

BD is an uncommon, multi-systemic inflammatory process whose aetiology and pathogenesis are unknown. It has a genetic component with non-Mendelian inheritance patterns.2 The disease is the most prevalent around the Mediterranean and in eastern Asia. Incidence in these regions is 1 to 10 cases/10000 inhabitants, while in northern Europe and the Americas, the rate is 1 to 2 cases per 1000000 inhabitants.3

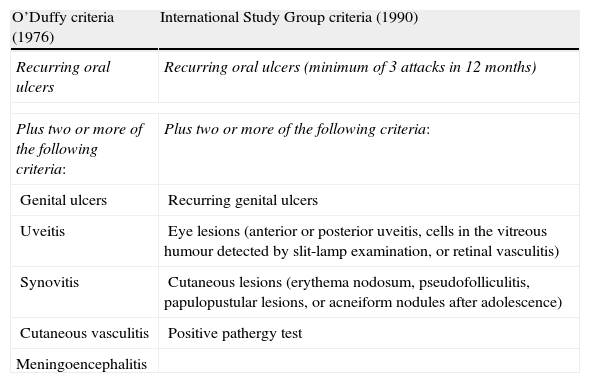

Diagnosis of BD is clinical since there are no pathognomonic symptoms or laboratory findings. Current diagnostic criteria were defined in 1990 by the International Study Group for Behçet's disease.4 Our patient meets both current diagnostic criteria and the older criteria described by O’Duffy (Table 1).

Older (1976) and current (1990) diagnostic criteria for Behçet disease.

| O’Duffy criteria (1976) | International Study Group criteria (1990) |

| Recurring oral ulcers | Recurring oral ulcers (minimum of 3 attacks in 12 months) |

| Plus two or more of the following criteria: | Plus two or more of the following criteria: |

| Genital ulcers | Recurring genital ulcers |

| Uveitis | Eye lesions (anterior or posterior uveitis, cells in the vitreous humour detected by slit-lamp examination, or retinal vasculitis) |

| Synovitis | Cutaneous lesions (erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis, papulopustular lesions, or acneiform nodules after adolescence) |

| Cutaneous vasculitis | Positive pathergy test |

| Meningoencephalitis | |

Recurrent oral ulcers tend to be the first manifestation of BD, although genital ulcers are a more sensitive sign in terms of diagnosis. Skin lesions tend to be papulopustular or acneiform in men and erythematous and nodular in women. The pathergy phenomenon, which is almost specific to BD, is only positive in 25% of these patients.5,6

Clinical, epidemiological, CSF-related, serological, and radiological data permitted us to diagnose neuro-Behçet disease. Other entities that should be considered in the differential diagnosis include demyelinating diseases, infiltrating tumours, vasculitis, other inflammatory diseases, ischaemic stroke, and most importantly, infectious diseases. Important entities in the latter category include HSV (which can cause urogenital ulcers associated with encephalitis); meningovascular syphilis (presents with headache and meningism in addition to cranial nerve paralysis and genital ulcers); Lyme disease; and tuberculosis. Since rhombencephalitis was present, we considered listeriosis even though the patient did not belong to any of the at-risk groups (pregnant, paediatric, and immunocompromised patients) and blood cultures were negative, which would be uncommon in this infection.7 Regarding the aetiology of different types of rhombencephalitis, a recent study has shown that its most common causes are idiopathic, demyelination, BD, and Listeria infection, in that order.8

NB is one of the causes of increased morbidity and mortality in BD.9 Its frequency is between 9% and 4%.10 The disease is more frequent and aggressive in males.9,10 Onset of NB occurs at about age 30, typically 4 to 5 years later than the appearance of systemic symptoms.11,12 The disease begins as NB in up to 6% of the cases,3 which can hamper diagnosis, especially in regions with a low BD prevalence.13 NB is normally central and intraparenchymal (accounting for 75% of cases12 and usually involves myelitis or BME10 that spares the red nucleus).14 Lesions tend to be hyperintense in T2-weighted sequences and the topography often includes the midbrain, pons, basal ganglia, and white matter. Spectroscopy of the thalamus shows decreased levels of N-acetyl aspartate with respect to healthy controls.14 Extraparenchymal forms have a better prognosis6 and are caused by episodes of venous thrombosis (with subacute intracranial hypertension) or arterial thrombosis (resulting in stroke).11,15 Behavioural and extrapyramidal disturbances, seizures, and emotional lability are infrequent.3,6 Common CSF findings include slightly increased protein levels, no oligoclonal bands, and mononuclear or polynuclear pleocytosis (0–400×106cells/L).

Treatment is complex given the clinical heterogeneity of NB and the lack of controlled trials. Megadoses of intravenous methylprednisolone with prednisone are used as maintenance treatment during attacks. Oral immunosuppressants are added following a second attack, although only azathioprine has been associated with a lower NB incidence rate.16 Cyclosporin is not recommended since it exacerbates neurological symptoms when used to treat uveitis.16 Tumour necrosis factor antagonists such as infliximab and etanercept are reserved for very aggressive forms of the disease, relapses after immunosuppressant treatment, or poor response to steroids.17 Venous sinus thrombosis is treated with antithrombotic drugs. Choice of drug and length of treatment are controversial topics.18

Regarding prognosis, patients tend to respond well to steroids, and only a third of them suffer relapses or progressive disease. Up to 20% of these patients have died at 7 years after diagnosis, which testifies to the severity of the disease.11,12

In conclusion, BD should be included in the differential diagnosis of BME cases. BD is even more likely if BME is associated with mucocutaneous lesions (especially urogenital ulcers) or if the red nucleus is unaffected.

Please cite this article as: Cabrera Núñez A, et al. Meningoencefalitis troncoencefálica como presentación de enfermedad de Behçet. Neurología. 2013;28:255–7.