The relationship between vascular events (VE) and cancer is well known; cancer provokes an increase in prothrombotic activity by releasing agents such as tumour necrosis factor and certain types of interleukins (especially 6 and 1) which are potent activators of the coagulation cascade.1 Nevertheless, the relationship between chemotherapy agents and VE, especially cerebral infarcts, is less well known. That being said, several published articles link certain chemotherapy agents to the appearance of VE, although the incidence is very low (a series of 10936 patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy found an incidence of stroke of 0.137%2), and numerous articles highlight the relationship between cisplatin and VE.2–5

The mechanism by which chemotherapy agents promote the occurrence of VE is not currently well understood. A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain the effect of cisplatin, including endothelial dysfunction, apoptosis, direct vascular toxicity, atherosclerosis, tumour embolisation, hypomagnesaemia, etc, although none of these is a clear determining factor.4–8

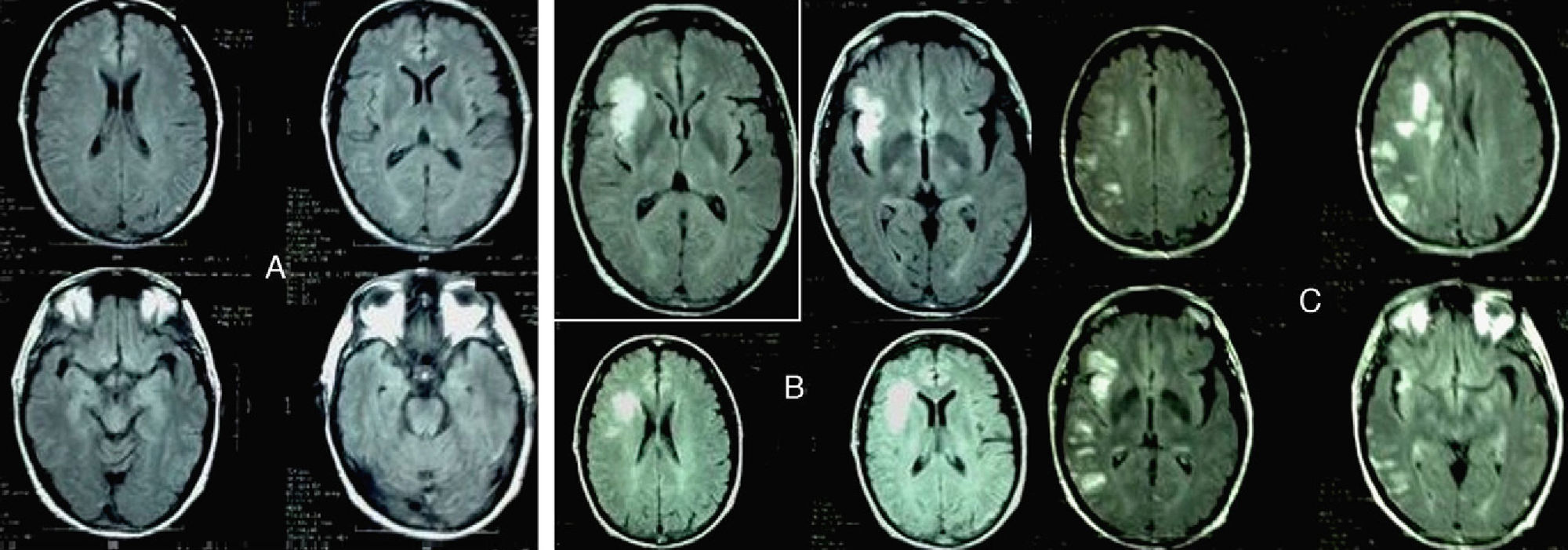

We present the case of a male patient aged 58 years, former smoker (in his youth), undergoing periodic venesection as treatment for haemochromatosis. A few months prior to first being admitted by our department, he presented with deep vein thrombosis and secondary pulmonary thromboembolism. The diagnostic examination detected a pulmonary mass which was later confirmed to be a large cell pulmonary carcinoma. The extended study confirmed the presence of bone metastasis. Meanwhile, a neuroimaging study (cranial MRI) ruled out brain cancer (Fig. 1A). Based on this diagnosis, we prescribed anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin and chemotherapy with cisplatin+gemcitabine+bisphosphonates. Two weeks later, the patient was admitted to our service with sudden onset dysarthria and facial droop; these symptoms persisted more than 24 hours. At that time, cranial MRI confirmed a subacute right-sided insular infarct (Fig. 1B). A colour Doppler ultrasound study of the supra-aortic and intracranial arteries found no haemodynamically relevant results. The patient also underwent electrocardiographic monitoring during 48 hours, which revealed no heart rate abnormalities. Thrombophilia testing, however, discovered factor V Leiden mutation and activated protein C resistance. We therefore decided to increase the patient's heparin dose with respect to that administered prior to hospitalisation. The patient returned to the emergency department 15 days later due to a new ictal event, which manifested as altered level of consciousness, clonic movements and loss of strength in the left arm. At the time of the neurological examination, he showed pronounced bradypsychia, left homonymous hemianopia with accompanying sensory extinction and facial asymmetry (NIHSS: 4). An additional cranial MRI confirmed the presence of new cortical and subcortical ischaemic lesions in the vascular territory of the right middle and posterior cerebral arteries (Fig. 1C). Results from all other studies, including the echocardiogram, were normal once again.

(A) Baseline cranial MRI (FLAIR sequence) taken at the time the patient was diagnosed. (B) Cranial MRI. FLAIR sequences showing infarction in the vascular territory of the RMCA, taken upon patient's first hospitalisation. (C) Cranial MRI. FLAIR sequences taken upon the third hospitalisation.

To date, the relationship between stroke and chemotherapy has not been completely defined, particularly in patients with vascular risk factors such as hypercoagulability disorders (in our case, factor V Leiden mutation and activated protein C resistance). We know that certain chemotherapy agents, including cisplatin, favour the appearance of cerebral infarctions in patients with tumours, and that cancer patients may present an inherent prothrombotic state.1,3,4,8 The link between gemcitabine and cerebral infarctions is less evident, although it is true that 1 in 6000 patients suffers from thrombotic microangiopathy due to causes that are not completely understood. We do know, however, that the condition increases procoagulant activity, reduces anticoagulant synthesis, stimulates platelet aggregation and favours endothelial damage.9–15

In the case of this patient, both ictal events coincided chronologically with intravenous administration of chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine (the first event occurred 17 days after the first cycle of chemotherapy and the second on the same day as the second cycle of chemotherapy). It seems unlikely that thrombotic microangiopathy would be responsible for the events; the patient had no renal function disorders, thrombocytopenia, or signs of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. However, the appearance of a new cerebral thrombotic event immediately after the second cycle of chemotherapy leads us to believe, quite logically, that gemcitabine played an important role in that event. Most infarctions associated with cisplatin chemotherapy occur a few days after the dose is administered. On the other hand, we should point out that although vascular events are uncommon in patients undergoing chemotherapy, as suggested by the literature (several studies of different types of cancer and chemotherapy cycles cite incidence rates ranging between 2% and 8% of the patients being treated11,16), treatment should be suspended if they do occur. In our case, the decision to continue with an additional cycle of chemotherapy resulted in a second ischaemic event. Furthermore, there have been no further strokes since the chemotherapy agent was changed (a new cycle of chemotherapy with no cisplatin or gemcitabine was started more than a month ago and no ischaemic events have occurred).

In our opinion, the presence of vascular risk factors, such as abnormalities revealed by thrombophilia testing, must be taken into account when a patient begins a chemotherapy programme. An appropriate risk-benefit analysis must be performed at the outset, and if the patient experiences a vascular event, chemotherapy should be suspended.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Domínguez J, et al. Infarto cerebral tras quimioterapia con cisplatino-gemcitabina: probable causa-efecto. Neurología. 2012; 27(4):245–7.