To determine if there is a relationship between environmental exposure to pesticides and the prevalence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) in Andalusia.

MethodWe carried out a case–control study using the logistic regression method to verify the relationship between the prevalence of ALS in the area exposed to pesticides versus the unexposed area, through the Odds Ratio statistical test.

ResultsThe study population consisted of 519 individuals diagnosed with ALS between January 2016 and December 2018 according to the CMBD (Minimum Basic Data Set) as cases. In the control group, we have 8,384,083 individuals obtained from data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE). The Odds Ratio (OR) was used as a measure of association between cases and controls, obtaining an OR between 0.76 and 1.08 for the confidence interval of the CI (95%).

ConclusionsDespite the existence of various studies that suggest a possible association between environmental exposure to pesticides and the risk of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, our analysis of the Andalusian population did not find significant evidence of this association.

Analizar si existe una relación entre la exposición ambiental a pesticidas y la prevalencia de esclerosis lateral amiotrófica (ELA) en Andalucía.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio de casos y controles con regresión logística para esclarecer la relación entre la prevalencia de ELA en el área expuesta a pesticidas vs. el área sin exposición, mediante el cálculo de razón de probabilidades (odds ratio [OR]).

ResultadosIncluimos un grupo de casos, con 519 individuos diagnosticados de ELA entre enero de 2016 y diciembre de 2018, obtenidos del conjunto mínimo básico de datos, y un grupo control con 8.384.083 individuos obtenidos de la base de datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Se utilizó la OR para medir la asociación entre casos y controles, con un intervalo de confianza del 95% de 0,76-1,08.

ConclusionesA pesar de que varios estudios sugieren una posible asociación entre la exposición ambiental a pesticidas y un aumento en el riesgo de ELA, nuestro estudio sobre la población andaluza no halló datos significativos en favor de dicha hipótesis.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a degenerative disease of unknown origin that affects motor neurons and is rapidly and fatally evolving.1

The estimate of ALS patients in Spain according to the Spanish Neurology Society is 3 new cases of ALS per day, which supposes an annual incidence of 1/100,000 inhabitants and a prevalence of 3.5/100,000. The global incidence is 1.5–2.7 new cases/100,000 inhabitants per year. At this time, ALS figures in Spain affect more than 3000 people, with a prevalence ranging from 2 to 5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. The frequency of appearance is slightly higher in the male gender (ratio: 1.3–1.5: 1), with an incidence that increases from the age of 40 and peaks at 70–75 years, to decrease until equalizing as the age of diagnosis increases. The death of these patients usually occurs 2 to 4 years after the start, although it can vary from months to decades, generally as a consequence of respiratory failure.2

The etiology of ALS is still, to a large extent, of unknown origin; however, there are studies that point to genetic and/or environmental factors as predisposing factors for their development and appearance. Other factors identified as possible predisposing factors for the appearance of ALS can be environmental toxins, tobacco, brain injuries, etc. However, it should be noted that to date, neither genetics nor environmental factors individually have been able to demonstrate sufficient evidence of their involvement in the development of ALS.3,4

A study by Feng-Chiao et al., in which 156 cases and 128 controls participated, determined that there was a statistically significant association between exposure to pesticides and the presence of ALS (odds ratio of 5.09 95% CI, 1.85–13.99; p=.002).5

A meta-analysis by Casanova et al. in 2016, it was concluded that there seems to be a causal relationship between exposure to pesticides and the development of ALS (Odd ratio of 1.42 95% CI, 1.09–1.86; p=0.001), although this could be also related to other factors.6

Another study by Povedano et al., carried out in Catalonia, points out an association between environmental exposure to pesticides and the appearance of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.7

Areas of Andalusia exposed to pesticidesThe coastline of Eastern Andalusia concentrates the main protected horticultural production area of the Andalusian autonomous community. Since 2001, the Junta de Andalucía has been mapping greenhouses on the Eastern Andalusian coast (regions of Campo de Dalías, Campo de Níjar and Bajo Andarax and Bajo Almanzora in Almería, La Costa in Granada and Vélez-Málaga in Málaga). Although most of the greenhouse surface in the provinces of Almería, Granada, and Málaga is found in the five regions studied since 2001 (96% according to SigPac), in 2017 it was decided to extend the study to other regions where it was detected the presence of greenhouses. Specifically, the study is extended to the Alto Andarax, Campo Tabernas, and Río Nacimiento regions in Almería, Alhama, Las Alpujarras, and Baza in Granada and Centro-Sur or Guadalhorce in Malaga. In this way, since 2017, the studied area would include more than 99% of the protected surface in the set of the three provinces according to SigPac data. The area of greenhouses estimated for the year 2019 in the regions studied amounted to 35,946 has registered an increase of 457ha (1.3%) compared to 2018. By provinces, in Almería 32,048ha have been estimated, 434ha more than the last year. In Granada, 3122ha have been estimated, 22ha more than last year. In Malaga, 776ha have been estimated, 1ha more than last year.3

According to the 2019 mapping of crops under plastic in Huelva, the area mapped as cultivation under plastic would amount to 16,611ha. It has been estimated that 14,616ha would correspond to the surface under plastic while the rest would correspond mainly to corridors of the exploitation and roads. If we compare these estimates with the results of the previous season, an increase in the area under plastic is observed of 796ha (6%). Since 2004, the area under plastic in Huelva has increased by 103% (7419ha). The municipalities of Moguer and Almonte concentrate almost half of the estimated total area under plastic (42%). They are followed in the amount of estimated protected area by the municipalities of Lepe, Lucena del Puerto, and Cartaya, which exceed 1000ha. At the opposite extreme, in Punta Umbría and San Juan del Puerto, they do not reach 10ha. Gibraleón followed by Lepe, Cartaya, and Almonte are the municipalities with the greatest increase in area. Another nine municipalities increase their surface to a lesser degree, between 10 and 50ha. The rest of the municipalities analyzed maintain their surface quite stable with variations that do not reach 10ha.4

As in the previous campaign, a small percentage of the area estimated as protected crop corresponds to areas where the plastic was not yet spread on January 12 and has been detected in the image of February 11.4

In Cádiz, seven municipalities have been studied: Chipiona, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Medina-Sidonia, Conil de la Frontera, Jerez de la Frontera, Arcos de la Frontera and Rota (96% of the area of protected crops in the province according to the census), estimating a protected area of 888ha compared to 919ha in 2014, 3.4% less. Sanlúcar de Barrameda and Chipiona account for most of the greenhouses (78%). In all municipalities except Conil de la Frontera, the estimated protected area has decreased slightly. In Arcos de la frontera, traveling macro-tunnel-type structures have been detected. In Seville, seven other municipalities have been studied: Los Palacios y Villafranca, Lebrija, Las Cabezas de San Juan, Aznalcázar, Alcalá de Guadaira, Utrera and El Cuervo de Sevilla (79% of the area of protected crops according to census), estimating a Protected area of 292ha compared to 261ha in 2014, 11.7% more. Los Palacios and Villafranca, followed by Lebrija, are the two municipalities with the highest presence of greenhouses (72%). The increase in area is especially concentrated in Los Palacios and Villafranca. In Aznalcázar, traveling macro-tunnel-type structures have been detected.8

Pesticides are widely used throughout the world due to their benefits for the agriculture sector, improving crop production, and in public health for the control of vector-borne diseases. In Spain, the use of pesticides as plant protection is 73,286 tons in its latest study in 2018.9

Long-term use of pesticides in areas of intensive use for agriculture contributes to environmental pollution; therefore, residential proximity to pesticide-treated farmland can pose a risk to human health.10

The purpose of our study is to determine, through a case–control study, if there is a relationship between environmental exposure to pesticides and the appearance of ALS in southern Spain.

Materials and methodsA case–control study based on the population of Andalusia (southern Spain) exposed to pesticides in their work environment in agriculture was conducted in order to evaluate a possible association between exposure to these chemicals and the prevalence of Sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Torrecárdenas University Hospital.

Criteria for the selection of study areas and categorization of pesticide exposureThe areas studied correspond to municipalities in Andalusia (Southern Spain), which were classified into two groups (high versus low exposure to the use of pesticides) according to the agronomic criteria provided by the Andalusian Council of Agriculture, in particular tons of pesticides used, and a land area dedicated to intensive agriculture in plastic-covered greenhouses.11

Intensive agriculture areas with a large number of hectares (ha) of a greenhouse, and therefore with high use of pesticides, were considered high exposure. In contrast, areas with a low number of greenhouse hectares or dedicated only to extensive agriculture (and therefore with low use of pesticides) were classified as low exposure to pesticides. The exhibition included the entire autonomous community of Andalusia, distinguishing in the provinces of Seville, Huelva, Cádiz, Málaga, Granada and Almería between high and low exposure, and Córdoba and Jaén being classified as the entire province of low exposure according to the cartography for 2018 due to its low number of greenhouse hectares.4,8,10,11

Regarding the main groups of phytosanitary products used during the study period according to the phytosanitary marketing survey in 2018 were fungicides and bactericides (52%: inorganic, carbamates and dithiocarbamates, benzimazoles, imidazoles and triazoles, morpholines, microbiological or botanicals), herbicides (23%: triazines and triazinones, carbamates and bicarbamates, urea, uracil or sulfonylure, others), molluscicides, growth regulators and others (16%: growth regulators, molluscicides and others), insecticides and acaricides (9%: pyrethroids, microbiological/botanical origin, others).9

Study population and Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisFor our population sample, we selected the 519 individuals diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis according to the Minimum Basic Data Set (CMBD) for the year 2018 in Andalusia, which we later divided into high and low exposure.

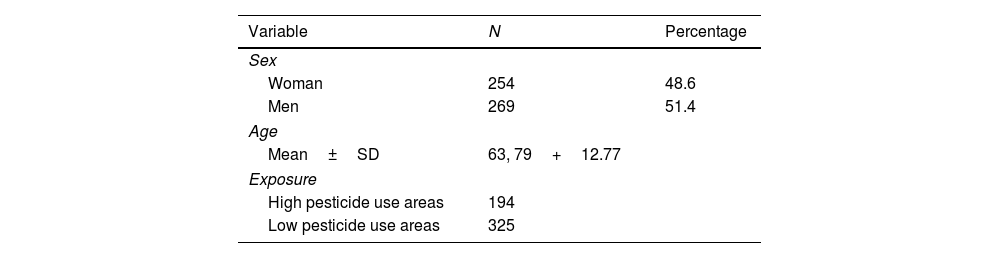

Of the individuals with ALS diagnoses, 194 people lived in high pesticide use areas and 325 people lived in low pesticide use areas. Of those 519 patients, 269 are men (51.4%) and 254 women (48.6%). The average age is 63, 79+12.77, with ages between 21 and 92 years (Table 1).

We selected the “cases” group through the computerized registry of the Andalusian Public Health Service, called the Basic Minimum Data Set (CMBD), among the patients diagnosed with ALS during the 3-year study period and in turn we divided them among those who lived in an area of intensive agriculture in greenhouses (high exposure) and those who did not (low exposure). The CMBD is a registry that collects coded clinical data on patients from admission to discharge from a public hospital, with data on their health status as the main diagnosis, as well as other secondary diagnoses, and other data such as age, sex and the place of residence.

The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was defined according to the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) of the World Health Organization, in force during the study period. The codes used to obtain the data for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) in the CMBD according to the ICD-10 were G12.21, in section G10-G14.

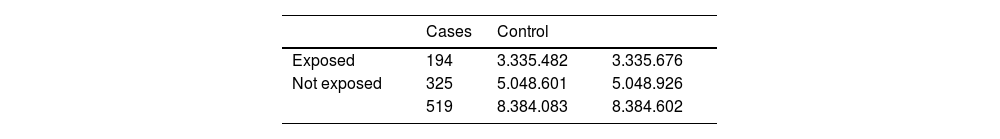

We select the “control” group through Andalusian population that lived in the same study areas as the cases, according to the INE for the period of time studied, and was composed of 3.335.482 people without a diagnosis of ALS in the high-exposure area and 5.048.601 people no diagnosis of ALS in the low-exposure zone, as of January 1, 2018.

Statistical analysisIn data analysis, frequencies and percentages were calculated for the variables sex and age in the sample obtained from cases of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, as well as the means and standard deviations of these variables. For the calculation of the prevalence rate, as well as the risk of developing Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, they were calculated for areas of high and low exposure to pesticides through the Odds Ratios (OR) test, with an interval of 95% confidence (CI). The level of statistical significance was established at p<0.05. The data were analyzed with the statistical program SPSS 24.0 for the analysis of frequencies and percentages, and Epidat 3.1 for the calculation of OR using a 2×2 contingency table (Table 2).

ResultsTo find out if there is a relationship between environmental exposure to pesticides and the prevalence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Andalusia, we analyzed the cases identified according to the CMBD in each of the municipalities included in the districts with high exposure to pesticides.

In the province of Almería, 46 cases of ALS were identified in total, 33 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides and 13 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

The province of Cádiz registered 87 cases of ALS in total, 61 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides, and 26 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

In the province of Granada, 40 cases of ALS were identified in total, 5 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides and 35 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

In the province of Huelva, 34 cases of ALS were identified in total, 26 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides and 8 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

In the province of Malaga, 88 cases of ALS were identified in total, 42 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides and 46 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

In the province of Seville, 124 cases of ALS were identified in total, 27 of them, inhabitants of areas of high exposure to pesticides and 97 inhabitants of areas of low exposure to pesticides.

The provinces of Córdoba and Jaén were included in their entirety as areas of low exposure to pesticides due to the low percentage of registered greenhouse hectares, identifying 67 and 33 cases of ALS diagnosed, respectively.

With the data obtained for the cases according to the CMBD and taking as a reference for the controls, the population by municipalities according to the INE for the year 2018, the 2×2 contingency table that appears in Table 1 was performed.

When analyzing the data through the Epidat 3.1 program for the contingency table shown in Table 1, it was identified that the proportion of cases exposed to pesticides was 37% (0.37) while that of exposed controls 87% (0.87)

The Odds Ratio (OR) was used as a measure of association between cases and controls, obtaining an OR 0.09 for the 95% confidence interval, between 0.76 and 1.08.

DiscussionThe present study evaluated whether living in geographic areas of intensive agriculture with a high percentage of greenhouse hectares (>1200ha) and therefore, with greater environmental exposure to pesticides in Andalusia is associated with a higher prevalence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

In recent years, several studies have pointed out the possible relationship between exposure to pesticides, and its implication as a risk factor for the appearance of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

A study based on a systematic review in 2016 identified 448 articles linking pesticide exposure and a series of diseases. Of these, 18 studies (15 case–control studies and 3 cohorts) evaluated the relationship between pesticide exposure and the incidence of ALS. Ten of the 15 case–control studies identified an association between pesticide exposure and the occurrence of ALS, with Odds Ratios (OR) between 1.1 and 6.12

A 2014 meta-analysis identified 19 case–control studies and 3 cohort studies, which also found an association between ALS risk and pesticide exposure with an OR of 1.44, for a Confidence Index of 95% (1.22–1.70) However, they did not find an association between ALS risk and exposure in rural settings.13

Another meta-analysis of 8 studies determined that there is significant evidence between the association of pesticide exposure and the appearance of ALS, with an OR between 1.4 and 1.8. However, when comparing the data from the Agricultural Health Study, with a cohort study of 84.739 private workers who use pesticides and their spouses, in this case an association was found only in the case of organochlorine pesticides.14

Another case–control study conducted in 2011, in which 156 patients diagnosed with ALS among the cases and 128 people without a diagnosis of ALS in the controls, evaluated the relationship between environmental exposure to pesticides and the incidence of ALS cases, yielding a result that identifies a statistically significant association between pesticide exposure and the development of ALS with an OR of 5.09 for a 95% CI (1.85–13.99) and a p<0.05 (p=0.002).15

However, most studies to date have focused on the study of pesticide exposure; leaving aside the role of non-work-related exposure, such as intake, dermal contact, and inhalation, which can derive from the application of pesticides to agricultural fields, as well as their volatilization after application, a fact that depends on the turn from specific pesticides and weather conditions. This generally occurs in areas of agricultural proximity.11,16

Another study of 290 cases (41.3%) and 1184 controls (43.3%) carried out with people who had agricultural crops in their homes, determined that there was no relationship between ALS risk and proximity to agricultural land under general non-intensive cultivation (OR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.78-1.09).17

The present study did not find evidence of a relationship between the prevalence of ALS and exposure to pesticides in geographic areas of high exposure in the autonomous community of Andalusia.

ConclusionsThe results obtained in this study allow us to affirm that there is no significant evidence to justify a relationship between the prevalence of ALS and environmental exposure to pesticides in geographic areas of high exposure in the autonomous community of Andalusia.

However, as it is a rapidly evolving disease with a low incidence, it is difficult to carry out adequate follow-up over time to obtain significant results, leaving this line open for future research.

FundingNot applicable.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.