Haberland syndrome, also known as encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis, is an extremely rare condition characterised by predominantly unilateral neurocutaneous malformations manifesting as early as during gestation.1 Haberland and Perou first described the syndrome in 1970 based on clinical and autopsy findings from a 51-year-old man with epilepsy and intellectual disability.2 Lesions are most frequently unilateral and are usually associated with such other alterations as alopecia, arachnoid cysts, porencephalic cysts, intracranial calcifications, intracranial and cervical spinal lipomas, cerebral atrophy, leptomeningeal granulomatosis, hydrocephalus, polymicrogyria, alterations in lamination of brain structures, desmoid tumours in the face and scalp, and periorbital anomalies.3 Cardiac lipomatosis has also been described in patients with the disease.4 Some of the most frequent clinical features include partial seizures, hemiplegia, and non-progressive mental retardation; the severity of these manifestations is highly variable. Seizures usually present a wide range of clinical patterns; they initially appear in childhood, causing varying degrees of psychomotor delay and motor dysfunction. Some patients neither experience seizures nor display intellectual disability. Other neurological manifestations include spasticity and facial nerve paralysis.3,5 Some authors have reported cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage secondary to vascular malformations.6,7 The wide range of neurological manifestations of Haberland syndrome makes purely symptomatic diagnosis a challenge.

We present the case of a 15-year-old boy who was referred to our hospital due to alopecia, multiple episodes of seizures since childhood, and phakomatous lesions on the face and scalp. The patient was born in 2001. His mother had a relatively severe episode of flu-like symptoms during the final stages of gestation; the aetiology of the episode was not confirmed. The patient's medical history notes complications during delivery, which may have caused fetal distress. During childhood, the patient experienced multiple seizures, mainly generalised tonic-clonic seizures and particularly affecting the right side of his body. In most cases, seizures were preceded by fever and symptoms of nasopharyngeal inflammation, and were therefore classified as febrile seizures. According to neurological reports, however, some episodes included left-sided focal motor seizures associated with ispilateral head deviation, and other episodes were compatible with atonic seizures characterised by generalised muscle weakness, drowsiness, and sphincter relaxation.

Neurological alterations persisting at the time of the consultation included cerebral palsy, mild macrocephaly, psychomotor delay, left-sided pyramidal signs, and ataxia of central origin aggravated by lumbar scoliosis and lower limb dysmetria.

The patient had multiple skin alterations, including bilateral frontal and left-sided temporal alopecia, a low hairline, and numerous polypoid cutaneous nodules, diagnosed as fibrolipomas, which were irregularly distributed over the face and scalp.

He also had bilateral clinodactyly of the fifth finger, delayed bone age, strabismus in the right eye, and recurrent episodes of pharyngoamygdalitis nearly from birth.

During early childhood, the patient underwent numerous imaging studies. At age one, a cranial CT scan displayed cortical atrophy mainly affecting the frontal lobes. Another cranial CT scan performed at age 5 also revealed bilateral cortical calcifications adjacent to the upper and middle portions of the parietal lobes.

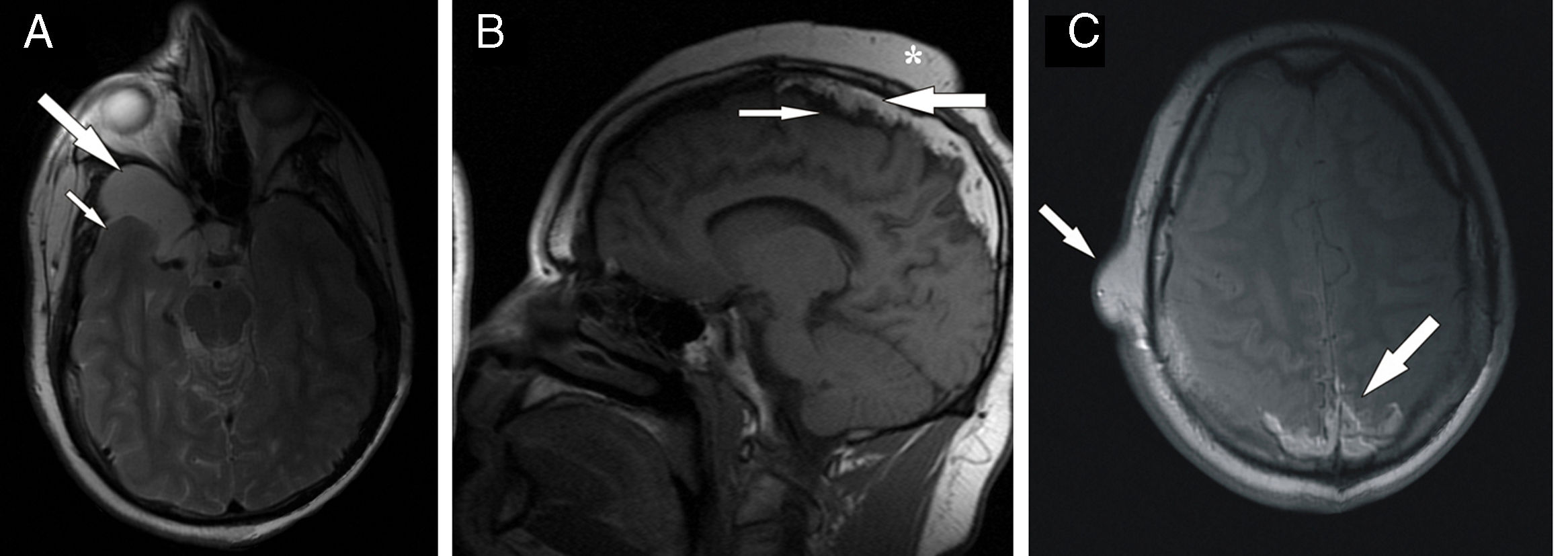

Between ages 10 and 15, the patient's admissions to hospital drastically decreased in frequency, coinciding with administration of antiepileptic treatment (phenobarbital plus carbamazepine). After this period, the frequency and severity of tonic-clonic seizures increased again. The patient underwent numerous electroencephalographic studies, which yielded non-specific results. Finally, coinciding with worsening of epilepsy, the patient was referred to our hospital's radiodiagnostics department to undergo a brain MRI, which led to a definitive diagnosis of Haberland syndrome. The MRI scan showed cerebral atrophy and confirmed that the mass located on the right portion of the middle cranial fossa was an arachnoid cyst. The latter appeared as a homogeneous, well-defined lesion and was hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and moderately hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 1). Cerebral calcifications were not as clearly visible on MRI as on CT. The MRI scan revealed patchy hypointense areas on T1- and T2-weighted sequences; these were located mainly at the midline, under the superior convexity, affecting the cortical parietal convexity bilaterally (Fig. 1). In addition to these, the most important finding for diagnosis was extra-axial accumulation of fat. The fat was also located at the midline, under the superior convexity, in the same area as the calcifications; and on the parietal and occipital cortex (Fig. 1). The fat was hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted sequences and seemed to constitute the main component of the pedunculated skin lesions of the patient's face and scalp.

MRI scan. (A) Axial T2-weighted sequence with CSF signal suppression showing atrophy of the right temporal lobe (small arrow) and a well-defined, hyperintense cystic lesion in the middle fossa, corresponding to an arachnoid cyst (large arrow). (B) Sagittal T1-weighted sequence displaying typical features of Haberland syndrome: extensive hyperintensity adjacent to the superior convexity and midline, corresponding to intracranial lipomatosis (large arrow); hypointense cortical calcifications located below the lipomatous area (small arrows); and subcutaneous tumours on the scalp (asterisk). (C) Axial T1-weighted sequence at the level of the semioval centres: the lipomatous lesions are clearly visible in the posterior midline (large arrow). The image also displays a benign soft-tissue tumour on the right side of the temporal squama (small arrow).

Despite being an extremely rare and variable condition, Haberland syndrome has some distinctive clinical and radiological features. Both neurologists and radiologists should therefore evaluate these findings as a whole to diagnose the condition as early as possible.

Please cite this article as: González Ortega FJ, Céspedes Mas M, Ramírez Garrido F. Síndrome de Haberland. Clínica y neuroimagen como base para el diagnóstico. Neurología. 2018;33:552–554.