Primary progressive aphasia is a clinical syndrome characterised by a language deficit of neurodegenerative origin with no other cognitive manifestations, at least during the initial stages.1 Three clinical variants have been described to date (nonfluent, semantic, and logopenic), each associated with its distinct topography and anatomical pathology.3 Of the 3 variants, logopenic aphasia is mainly associated with Alzheimer disease, and it is considered an atypical form of AD onset.1 However, the association between logopenic aphasia and Alzheimer disease is still a matter of debate in the literature. Associations with other diseases have been found in a high percentage of cases in studies using molecular imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, or anatomical pathology findings.3,4 Furthermore, cognitive impairment and dementia associated with Parkinson's disease are regarded as frequent. They are characterised by executive and/or memory deficits, while language typically remains preserved.5 We present the case of a patient with idiopathic Parkinson's disease who developed symptoms of progressive logopenic aphasia. Her symptoms finally progressed to generalised dementia with biomarkers of Alzheimer disease, thereby supporting the idea that this type of aphasia is a marker of Alzheimer disease.

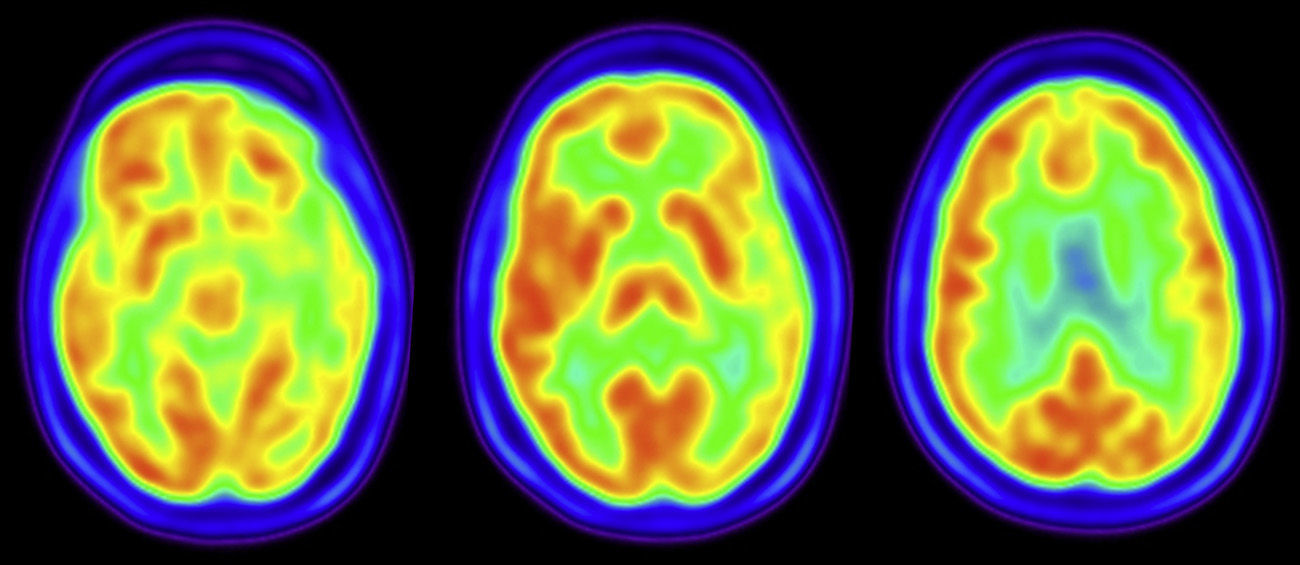

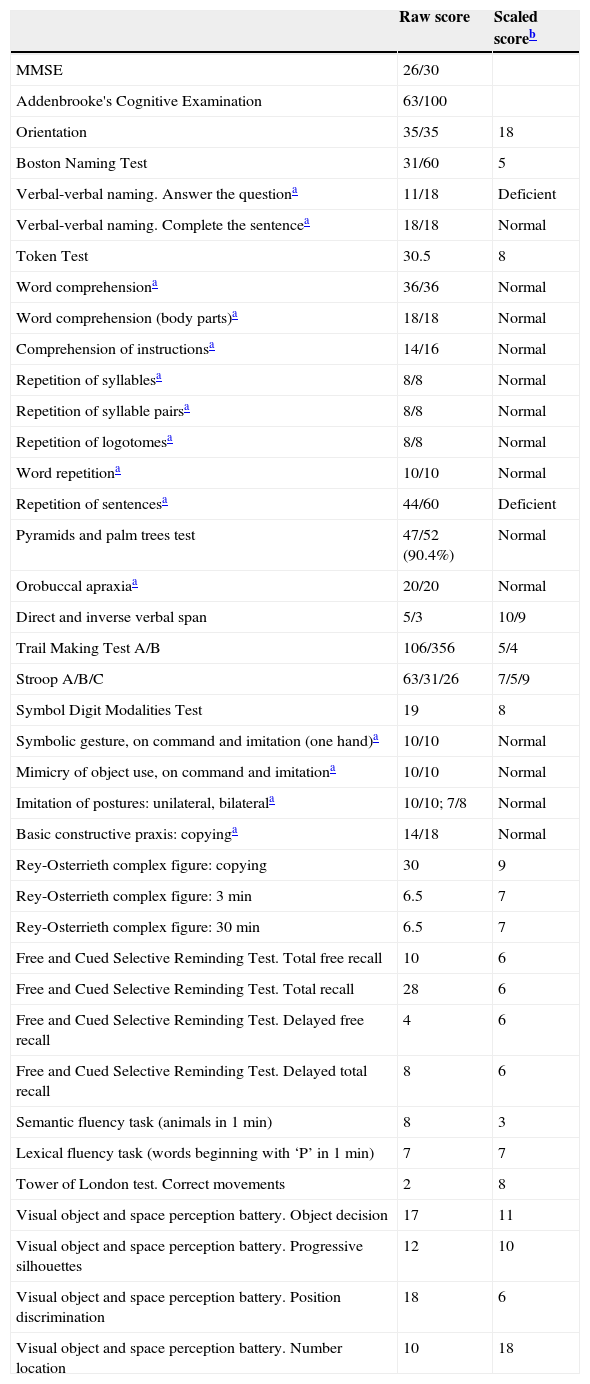

Our patient is a 65-year-old woman with high blood pressure and dyslipidaemia, who in 2009 was diagnosed with idiopathic Parkinson's disease after a one-year period in which she displayed slowness and tremor. Neurological examination revealed rigidity, bradykinesia, and resting tremor predominantly on the right side. She responded favourably to levodopa and subsequently developed motor fluctuations. She also presented REM sleep behaviour disorder. Since mid 2012, the patient began reporting increasing difficulty finding words without any associated memory impairment or behaviour disorder. She experienced no hallucinations and her neurological examination did not reveal oculomotor alterations, pyramidal signs, or cerebellar signs. Neuropsychological evaluation performed in early 2013 showed qualitative impairment of language fluency consisting of frequent pauses to find words, with no aphasic transformations and well-articulated speech. We observed anomic aphasia both in visual-verbal naming and verbal-verbal naming, and conduction aphasia, with preserved verbal comprehension, grammatical structures, and semantic usage. She also presented a mild divided attention deficit (TMT-Part B). Verbal memory tested as borderline, while the rest of the evaluation yielded normal results (Table 1). The PET-TC study showed left temporoparietal hypometabolism (Fig. 1) and magnetic resonance scan of that region revealed asymmetry. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid showed a decreased concentration of A-β42 proteins (199pg/mL, normal value >500pg/mL), increased T-protein (443pg/mL, normal value <400pg/mL), and increased phosphotau levels (62pg/mL, normal value <61pg/mL). Over the following months, the patient's clinical symptoms progressed and her speech symptoms grew more marked. Memory deficit, disorientation, and functional decline also began to manifest.

Results from the neuropsychological evaluation.

| Raw score | Scaled scoreb | |

|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 26/30 | |

| Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination | 63/100 | |

| Orientation | 35/35 | 18 |

| Boston Naming Test | 31/60 | 5 |

| Verbal-verbal naming. Answer the questiona | 11/18 | Deficient |

| Verbal-verbal naming. Complete the sentencea | 18/18 | Normal |

| Token Test | 30.5 | 8 |

| Word comprehensiona | 36/36 | Normal |

| Word comprehension (body parts)a | 18/18 | Normal |

| Comprehension of instructionsa | 14/16 | Normal |

| Repetition of syllablesa | 8/8 | Normal |

| Repetition of syllable pairsa | 8/8 | Normal |

| Repetition of logotomesa | 8/8 | Normal |

| Word repetitiona | 10/10 | Normal |

| Repetition of sentencesa | 44/60 | Deficient |

| Pyramids and palm trees test | 47/52 (90.4%) | Normal |

| Orobuccal apraxiaa | 20/20 | Normal |

| Direct and inverse verbal span | 5/3 | 10/9 |

| Trail Making Test A/B | 106/356 | 5/4 |

| Stroop A/B/C | 63/31/26 | 7/5/9 |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | 19 | 8 |

| Symbolic gesture, on command and imitation (one hand)a | 10/10 | Normal |

| Mimicry of object use, on command and imitationa | 10/10 | Normal |

| Imitation of postures: unilateral, bilaterala | 10/10; 7/8 | Normal |

| Basic constructive praxis: copyinga | 14/18 | Normal |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: copying | 30 | 9 |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: 3min | 6.5 | 7 |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: 30min | 6.5 | 7 |

| Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Total free recall | 10 | 6 |

| Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Total recall | 28 | 6 |

| Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Delayed free recall | 4 | 6 |

| Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Delayed total recall | 8 | 6 |

| Semantic fluency task (animals in 1min) | 8 | 3 |

| Lexical fluency task (words beginning with ‘P’ in 1min) | 7 | 7 |

| Tower of London test. Correct movements | 2 | 8 |

| Visual object and space perception battery. Object decision | 17 | 11 |

| Visual object and space perception battery. Progressive silhouettes | 12 | 10 |

| Visual object and space perception battery. Position discrimination | 18 | 6 |

| Visual object and space perception battery. Number location | 10 | 18 |

According to patient's age and years of education (8 years), using normative data from Neuronorma project. A scaled score less than or equal to 5 is considered deficient.10

The main signs of aphasia and findings from the FDG-PET study met diagnostic criteria for the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia,2 which subsequently progressed to overall cognitive impairment. In this case, we might suggest the association of 2 neurodegenerative diseases in the same patient (Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer disease), or else that logopenic aphasia had manifested as the initial form of dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Parkinson's disease and REM sleep behaviour disorder are indicative of dementia with Lewy bodies and alpha-synuclein aggregates, while biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid and the cognitive profile point to Alzheimer disease. An association between these 2 diseases is considered frequent in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease, and researchers have indicated that copresence of Alzheimer disease could influence the clinical presentation of the former.6 Recent anatomical pathology studies suggest that we recognise 2 main subgroups of dementia associated with Parkinson's disease: one subgroup characterised by neocortical alpha-synuclein deposition and another also featuring Aβ deposition. However, deposition of neocortical Tau associated with Aβ would be less frequent. These data seem to support the hypothesis that amyloid disease would also contribute to the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease; in contrast, an association between Alzheimer disease (Tau and Aβ deposition) and Parkinson's disease would be less frequent.7 Clinical distinction between subgroups, and especially determining which patients have concomitant amyloid pathology, could be relevant from a therapeutic point of view.

To our knowledge, only one other case of progressive aphasia in a patient with idiopathic Parkinson's disease has been reported in the literature.8 That patient was a woman who also presented hallucinations. Her FDG-PET study displayed more generalised impairment, and the PET scan with Pittsburgh compound B yielded negative results. These findings indicated that symptoms could be the result of cortical involvement in Lewy body disease.

In conclusion, presence of progressive aphasia in patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease suggests that this type of aphasia may also represent the onset of cognitive impairment, as do other clinical manifestations of posterior cortical deficit.9 In our case, detection of biomarkers of Alzheimer disease indicates that the presence of logopenic aphasia could also be a marker of amyloid disease in these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Matías-Guiu JA, García-Ramos R, Cabrera-Martín MN, Moreno-Ramos T. Afasia progresiva logopénica asociada a enfermedad de Parkinson idiopática. Neurología. 2015;30:521–524.

This study was presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology (Barcelona, 19–23 November 2013).