Anorgasmia is the inability to reach orgasm after any type of sexual stimulation.1 Sexual desire, psychological and physical stimulation, penile erection, and ejaculation typically precede the male orgasm.2 Erections are regulated by the parasympathetic nervous system through the inferior hypogastric plexus and by the somatic nervous system through pudendal nerve fibres, both of which arise from the sacral nerves S2 to S4.3 Ejaculation is conveyed through the hypogastric plexus originating in the sympathetic chain ganglia of the spinal cord segments T11 to L2.4,5 Involuntary smooth muscle contractions of the seminal vesicles and the striated muscles of the pelvic floor give rise to the release of semen associated with orgasm. The afferences involved in sexual pleasure activate such brain areas as the mesodiencephalic transition zone (which includes the mesencephalic tegmentum and the hypothalamus), subcortical structures (caudate nucleus, thalamus), the cerebral cortex (primarily the amygdala and the right neocortex), and even the cerebellum.6

Sexual function disorders as a result of such neurological conditions as head trauma, stroke, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, myelopathy, and peripheral neuropathy have previously been described in the literature.7

We present the case of a patient with isolated anorgasmia as an initial symptom of myelitis.

The patient was a 30-year-old man with no relevant medical or surgical history who presented at the urology department with anorgasmia. From adolescence to 20 years of age, the patient described satisfactory sexual desire, no erectile dysfunction, and normal ejaculations accompanied by orgasm. At the time of the consultation, however, he disclosed a complete loss of sexual pleasure over the previous 10 years, although all other sexual functions remained intact. He reported no urethral or anal sphincter dysfunction. Physical examination of the pelvic floor and the external genitalia, a scrotal Doppler ultrasound, a spermiogram, and a hormonal analysis (including testosterone, estradiol, prolactin, LH, and FSH) yielded normal results. The patient was referred to the neurology department, where an examination revealed normal results except for pallesthesia in the lower limbs.

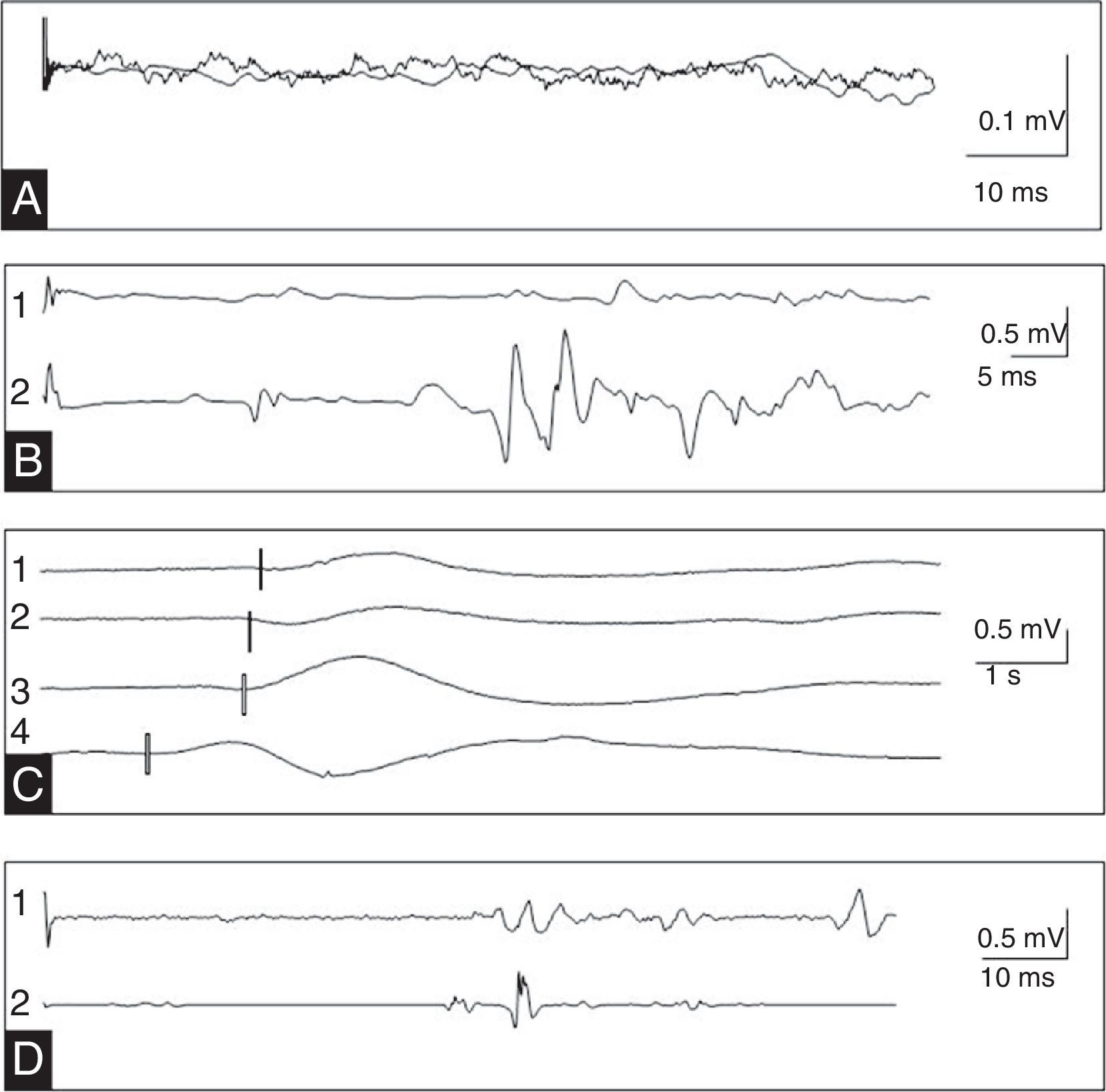

The neurophysiological study included an electromyography of the bulbocavernosus muscle and the external anal sphincter using concentric bipolar needle electrodes, a study of somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) from the internal pudendal nerve to the posterior tibial nerve, a registered transcranial magnetic stimulation of the bulbocavernosus muscle, a sympathetic skin response test of the perineum and limbs, a sacral reflex test (bulbocavernosus and anal), and a sural nerve sensory neurography. These studies revealed absence of SEP in the pudendal and posterior tibial nerves and normal results for the remaining parameters, which is indicative of injury to the somatosensory pathway at the level of the posterior column above the L1 segment (Fig. 1).

(A) Absent somatosensory evoked potentials in the internal pudendal nerve. (B) Registered transcranial magnetic stimulation of the bulbocavernosus muscle in relaxed state (1) and after motor facilitation (2) showed normal latency. (C) Sympathetic skin response to nociceptive stimulation of the right sole (1), the left sole (2), the right palm (3), and the perineum (4). (D) Right (1) and left (2) bulbocavernosus reflex with normal latency and symmetry.

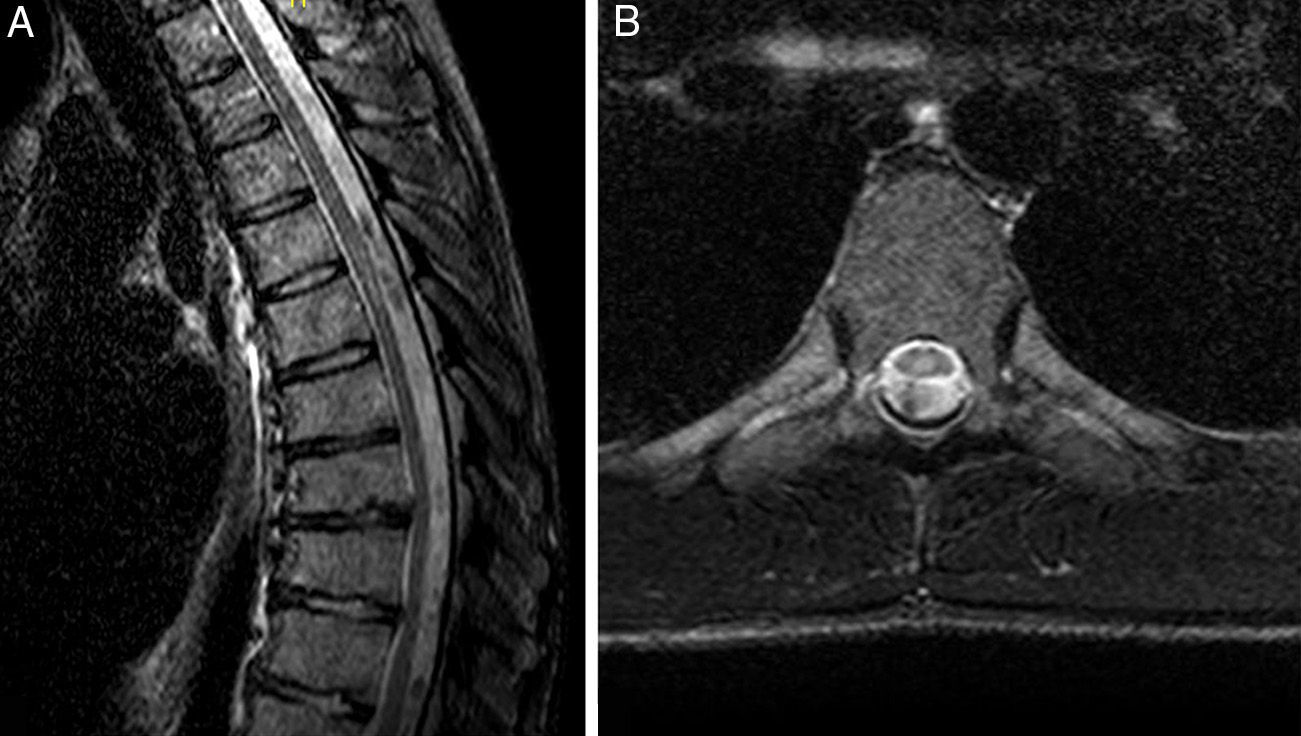

Cranial, cervical, dorsal, and lumbar MRI scans showed myelomalacia in the posterior spinal cord at T5-T6 level which was compatible with residual complications from myelitis (Fig. 2).

Blood analyses (including thyroid function and vitamin B12 levels), serological tests (HIV, HTLV, CMV, EBV, borrelia, syphilis), and autoimmune tests (ANA) did not reveal the aetiology of transverse myelitis.

The correlations between transverse myelitis and sexual syndromes has previously been described in the literature.8,9 Male anorgasmia as the sole sexual disorder after spinal cord lesions is unusual. Sensory alterations, motor symptoms, and sphincter dysfunction are concomitant symptoms that depend on the location and size of the lesion.10 In this particular case, the normal sympathetic skin response of the perineum is compatible with the preservation of the sympathetic pathway from the sympathetic chain ganglia at T11-L2 to pelvic nerves and, consequently, intact erectile function. Anal and bulbocavernosus reflex studies indicated no pelvic floor sensorimotor or reflex arc impairment. These systems regulate the striated sphincters, sensitivity of dermatomes S2-S4, ejaculation, and the transmission of sexual pleasure. The absence of SEP and myelomalacia limited to the thoracic portion of the posterior spinal column explain the lack of afferent transmission of the orgasm as well as the pallesthesia. Preservation of the corticospinal motor pathway is confirmed by the results of the transcranial magnetic stimulation. The electromyography study and the neurography ruled out focal and systemic sphincter neuromuscular disorders, respectively.

Taking sexual histories and analysing sexual function is not common practise in neurology consultations. A basic sexual history and knowledge of the complementary tests available can help manage patients with sexual syndromes of possible neurological origin.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez Guerrico I, Royo I, Arango O, González S, Munteis E. Anorgasmia masculina como síntoma inicial de mielitis transversa. Neurología. 2016;31:414–416.