Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease traditionally defined as clinical symptoms involving the upper motor neuron, in the motor homunculus, and the lower motor neuron, in the spinal cord.1,2 However, recent publications have described non-motor signs and symptoms in patients with definite ALS, including impaired higher cerebral functions, signs of dysautonomia, metabolic disorders,3,4 and cognitive alterations linked to frontotemporal dementia.5 Post mortem histopathological studies of patients with definite sporadic ALS have identified protein inclusions of transactive response DNA binding protein 43kDa (TDP-43) in non-motor areas of the central nervous system (CNS), including the nigrostriatal system, cerebellum, forebrain, hypothalamus, and neocortical and allocortical areas.6,7 ALS and frontotemporal dementia are currently considered to be TDP-43 proteinopathies.

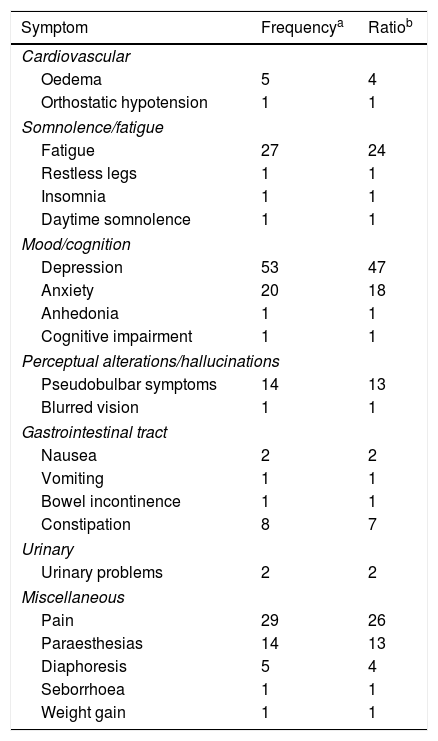

We performed a retrospective study of the medical records of 112 patients diagnosed with definite sporadic ALS according to the El Escorial clinical and neurophysiological criteria.8 We analysed the non-motor neurological signs and symptoms reported at the time of diagnosis and those manifesting in the first year of clinical follow-up. All patients with diagnosis of definite ALS were assessed with the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-r), the Mini-Mental State Examination, a neuropsychological test, a genetic test, and the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale during the baseline consultation, and underwent at least one additional evaluation during the one-year follow-up period. In our sample, we identified 25 non-motor symptoms, with the most prevalent being: depression (in 47% of patients), pain (26%), fatigue (24%), anxiety (18%), pseudobulbar symptoms (13%), and paraesthesias (13%) (Table 1). No diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia was established in any of our patients; curiously, all cases with pseudobulbar symptoms, depression, or anxiety were negative for the chromosome 9 hexanucleotide repeat expansion normally associated with pseudobulbar symptoms (C9Orf72 gene). We identified an average of 4.2±2.03 non-motor symptoms per patient. Patients with bulbar ALS presented a higher number of non-motor symptoms than patients with spinal ALS (5.41±1.61 and 3.85±2.01 non-motor symptoms per patient, respectively). Furthermore, we observed correlations between symptom pairs which may have similar pathophysiological mechanisms, including: anxiety and depression (χ2; P=.025), bladder incontinence and constipation (χ2; P=.017), and pain and paraesthesias (χ2; P=.027).

Non-motor symptoms of ALS, classified by domain, frequency, and ratio.

| Symptom | Frequencya | Ratiob |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Oedema | 5 | 4 |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 1 | 1 |

| Somnolence/fatigue | ||

| Fatigue | 27 | 24 |

| Restless legs | 1 | 1 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 1 |

| Daytime somnolence | 1 | 1 |

| Mood/cognition | ||

| Depression | 53 | 47 |

| Anxiety | 20 | 18 |

| Anhedonia | 1 | 1 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 1 |

| Perceptual alterations/hallucinations | ||

| Pseudobulbar symptoms | 14 | 13 |

| Blurred vision | 1 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | ||

| Nausea | 2 | 2 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 1 |

| Bowel incontinence | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation | 8 | 7 |

| Urinary | ||

| Urinary problems | 2 | 2 |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Pain | 29 | 26 |

| Paraesthesias | 14 | 13 |

| Diaphoresis | 5 | 4 |

| Seborrhoea | 1 | 1 |

| Weight gain | 1 | 1 |

A recent study by Cykowski et al.7 detected TDP-43 inclusions in the forebrain and hypothalamus, reporting a significant correlation between this histopathological finding and predominantly bulbar ALS. In our sample, patients with predominantly bulbar ALS presented more non-motor symptoms than patients with spinal ALS.

Clinical heterogeneity of ALS is characteristic9; the presence of pathological inclusions in non-motor areas of the CNS in cases of definite sporadic ALS may explain the presence of atypical symptoms, which are frequently omitted and therefore are not approached or treated adequately, limiting quality of life. In our sample, the non-motor symptoms observed in patients with ALS may be incidental manifestations due to disability, or clinical manifestations due to the progression of the neurodegenerative process. Timely identification of non-motor manifestations in patients with classic motor symptoms may facilitate medical treatment and improve the clinical condition of these patients. The wide variety of clinical phenotypes, the recent histopathological findings in the CNS, and the presence of non-motor symptoms suggest that ALS is a multisystemic disease which is not restricted to the motor system.

Please cite this article as: Martínez HR, Escamilla-Ocañas CE, Hernández-Torre M. Síntomas neurológicos extra-motores en pacientes con esclerosis lateral amiotrófica. Neurología. 2018;33:474–476.