Ocular myasthenia gravis (MG) is the most common phenotype of MG at onset. A variable percentage of these patients develop secondary generalisation; the risk factors for conversion and the protective effect of immunosuppressive treatment are currently controversial.

Patients and methodsWe designed a retrospective single-centre study with the aim of describing the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of a Spanish cohort of patients with ocular MG from Hospital Universitario de Albacete from January 2008 to February 2020.

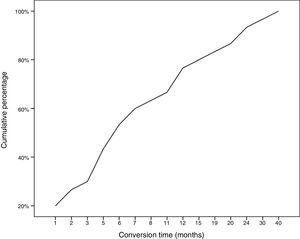

ResultsWe selected 62 patients with ocular MG from a cohort of 91 patients with MG (68.1%). Median age at diagnosis was 68 (IQR, 52–75.3), and men accounted for 61.3% of the sample (n = 38). Most patients presented very late-onset ocular MG (n = 34, 54.8%). Binocular diplopia was the most frequent initial symptom (51.7%). The rate of progression to generalised MG was 50% (n = 31), with a median time of 6 months (IQR, 2–12.8). Female sex (OR: 5.46; 95% CI, 1.16-25-74; P= .03) and anti—acetylcholine receptor antibodies (OR: 8.86; 95% CI, 1.15–68.41; P = .04) were significantly associated with the risk of developing generalised MG.

ConclusionsThe conversion rate observed in our series is relatively high. Generalisation of MG mainly occurs during the first 2 years of progression, and is strongly associated with female sex and especially with the presence of anti—acetylcholine receptor antibodies.

La miastenia gravis ocular (MGo) es la forma de presentación de la enfermedad más frecuente. Un porcentaje variable de estos pacientes desarrollan una forma generalizada (MGg), siendo los factores de riesgo de conversión y el efecto protector del tratamiento inmunosupresor objeto de controversia en el momento actual.

Pacientes y métodosDiseñamos un estudio monocéntrico retrospectivo, con el objetivo de describir las características demográficas, clínicas y de laboratorio de una cohorte española de MGo, a partir de una serie de MG registrada en el Hospital Universitario de Albacete desde enero del 2008 hasta febrero de 2020.

ResultadosSeleccionamos 62 pacientes con MGo de una cohorte de 91 sujetos con MG (68,1%). La mediana de edad al diagnóstico fue de 68 (RIQ 52–75,3), con predominio de MGo de inicio muy tardío (n = 34, 54,8%) y de varones (n = 38, 61,3%). La diplopía binocular fue el síntoma inicial más frecuente (51,7%). La tasa de conversión a MGg fue del 50% (n = 31), con una mediana de tiempo de seis meses (RIQ 2–12,8). Encontramos asociación significativa entre ser mujer (OR: 5,46, IC 95% 1,16-25-74, p = 0,03) y tener AcAchR (OR: 8,86, IC 95% 1,15-68,41, p = 0,04), con el riesgo de desarrollar una MGg.

ConclusionesLa tasa de conversión de MGo en nuestra serie es relativamente elevada. La generalización tiene lugar principalmente durante los primeros dos años de evolución y está asociada al sexo femenino y, sobre todo, a la presencia de AcAchR.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a clinically heterogeneous disease that may present with weakness and/or fatigability of skeletal muscles. Isolated involvement of the levator palpebrae superioris, orbicularis oculi, and/or extraocular muscles, which presents clinically as ptosis and/or diplopia, is the most frequent form of presentation of the disease, referred to as ocular MG (OMG).1,2 Some of these patients (10%–85%, depending on the series) develop secondary generalised MG (GMG) over the course of the disease, particularly in the first 2 years.3–5

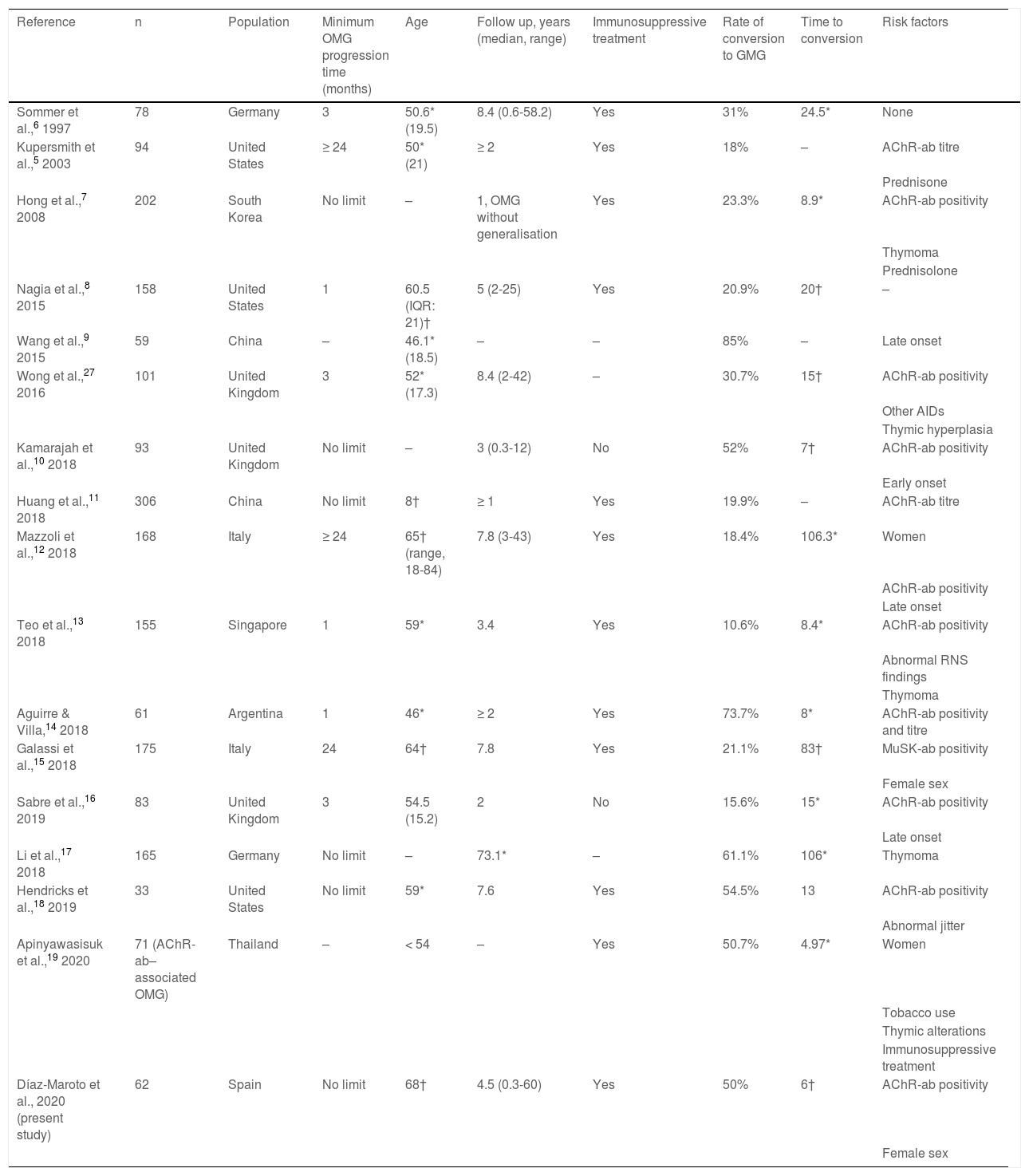

The significant impact of this secondary generalisation of OMG on the prognosis and treatment of these patients has led to the development of numerous studies aiming to identify risk factors for generalisation (Table 1) and to determine the effectiveness of immunosuppressive treatment and thymectomy as disease-modifying therapies.3,5–19 The limitations inherent to retrospective observational studies, together with differences in the inclusion criteria used, may partly explain the variability and the inconsistency of the reported results. The influence of ethnic factors and geographical origins on clinical and epidemiological aspects of MG20 also constitute a limiting factor for the extrapolation of findings to different populations.

Summary of previous studies analysing risk factors for conversion to generalised myasthenia gravis.

| Reference | n | Population | Minimum OMG progression time (months) | Age | Follow up, years (median, range) | Immunosuppressive treatment | Rate of conversion to GMG | Time to conversion | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sommer et al.,6 1997 | 78 | Germany | 3 | 50.6* (19.5) | 8.4 (0.6-58.2) | Yes | 31% | 24.5* | None |

| Kupersmith et al.,5 2003 | 94 | United States | ≥ 24 | 50* (21) | ≥ 2 | Yes | 18% | – | AChR-ab titre |

| Prednisone | |||||||||

| Hong et al.,7 2008 | 202 | South Korea | No limit | – | 1, OMG without generalisation | Yes | 23.3% | 8.9* | AChR-ab positivity |

| Thymoma | |||||||||

| Prednisolone | |||||||||

| Nagia et al.,8 2015 | 158 | United States | 1 | 60.5 (IQR: 21)† | 5 (2-25) | Yes | 20.9% | 20† | – |

| Wang et al.,9 2015 | 59 | China | – | 46.1* (18.5) | – | – | 85% | – | Late onset |

| Wong et al.,27 2016 | 101 | United Kingdom | 3 | 52* (17.3) | 8.4 (2-42) | – | 30.7% | 15† | AChR-ab positivity |

| Other AIDs | |||||||||

| Thymic hyperplasia | |||||||||

| Kamarajah et al.,10 2018 | 93 | United Kingdom | No limit | – | 3 (0.3-12) | No | 52% | 7† | AChR-ab positivity |

| Early onset | |||||||||

| Huang et al.,11 2018 | 306 | China | No limit | 8† | ≥ 1 | Yes | 19.9% | – | AChR-ab titre |

| Mazzoli et al.,12 2018 | 168 | Italy | ≥ 24 | 65† (range, 18-84) | 7.8 (3-43) | Yes | 18.4% | 106.3* | Women |

| AChR-ab positivity | |||||||||

| Late onset | |||||||||

| Teo et al.,13 2018 | 155 | Singapore | 1 | 59* | 3.4 | Yes | 10.6% | 8.4* | AChR-ab positivity |

| Abnormal RNS findings | |||||||||

| Thymoma | |||||||||

| Aguirre & Villa,14 2018 | 61 | Argentina | 1 | 46* | ≥ 2 | Yes | 73.7% | 8* | AChR-ab positivity and titre |

| Galassi et al.,15 2018 | 175 | Italy | 24 | 64† | 7.8 | Yes | 21.1% | 83† | MuSK-ab positivity |

| Female sex | |||||||||

| Sabre et al.,16 2019 | 83 | United Kingdom | 3 | 54.5 (15.2) | 2 | No | 15.6% | 15* | AChR-ab positivity |

| Late onset | |||||||||

| Li et al.,17 2018 | 165 | Germany | No limit | – | 73.1* | – | 61.1% | 106* | Thymoma |

| Hendricks et al.,18 2019 | 33 | United States | No limit | 59* | 7.6 | Yes | 54.5% | 13 | AChR-ab positivity |

| Abnormal jitter | |||||||||

| Apinyawasisuk et al.,19 2020 | 71 (AChR-ab–associated OMG) | Thailand | – | < 54 | – | Yes | 50.7% | 4.97* | Women |

| Tobacco use | |||||||||

| Thymic alterations | |||||||||

| Immunosuppressive treatment | |||||||||

| Díaz-Maroto et al., 2020 (present study) | 62 | Spain | No limit | 68† | 4.5 (0.3-60) | Yes | 50% | 6† | AChR-ab positivity |

| Female sex |

AChR-ab: anti–acetylcholine receptor antibodies; AID: autoimmune disease; GMG: generalised myasthenia gravis; IQR: interquartile range; MuSK-ab: anti–muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies; OMG: ocular myasthenia gravis; RNS: repetitive nerve stimulation. Values are expressed as means (*) or as medians (†), as reported in the studies cited.

In the light of the ongoing debate regarding the detection of patients with OMG at increased risk of secondary generalisation, and the limited amount of specific research on the subject in Spanish populations, this study aims to describe the main demographic, clinical, and serological characteristics of a series of patients with OMG and to analyse factors associated with progression to GMG.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive retrospective study using data from a cohort of patients diagnosed with MG and under follow-up by the neuromuscular diseases clinic at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete between January 2008 and February 2020. Clinical diagnosis of MG was confirmed with determination of anti–acetylcholine receptor antibodies (AChR-ab) and anti–muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies (MuSK-ab) in the serum. In patients with negative serology results, diagnosis was based on neurophysiological findings of a decremental response to low-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) or increased jitter in single-fibre electromyography. Of all patients with MG, we selected those who had presented the ocular form from disease onset and were under follow-up for at least 3 months, with no restriction on the minimum progression time of ocular symptoms prior to generalisation. Data were recorded on the typical demographic and clinical variables (sex and age of onset, stratified into 3 groups: early onset [≤ 50 years], late onset [51-65 years], and very late onset [≥ 65 years]), type of ocular symptom at onset (uni- or bilateral ptosis, diplopia, or both), presence and titre of AChR-ab and MuSK-ab, RNS and jitter findings (when these tests were performed), history of thymoma or thymectomy, and symptomatic and immunosuppressive treatments administered. We identified the subgroup of patients who progressed to weakness and/or fatigability of the facial, oropharyngeal, cervical, respiratory, axial, or limb muscles, and the time of presentation of these symptoms (time in months from initial manifestation of OMG to conversion to GMG). Finally, we analysed variables associated with conversion to GMG.

Clinical evaluation and review of patients’ electronic medical records were conducted by 2 neurologists with experience in neuromuscular diseases. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and patient data were stored in an anonymised database.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as percentages. Normality of data distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally-distributed variables are expressed as means (standard deviation [SD]), and the remaining variables are expressed as median (p25-p75). We subsequently conducted hypothesis testing to identify risk factors for generalisation, using the chi-square test, t test, and Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Finally, a multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was conducted to confirm which variables were independently associated with MG generalisation, calculating odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The threshold for significance was set at P < .05.

ResultsA total of 91 patients diagnosed with MG were attended at the specialist neuromuscular diseases clinic at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete between January 2008 and February 2020. Of these, we selected a series of 62 (67.4%) who presented ocular symptoms as the first and only manifestation of the disease at the time of diagnosis: 51.7% (n = 30) with diplopia, 32.8% (n = 19) with uni- or bilateral ptosis, and 15.5% (n = 9) with both; in 4 cases, the specific symptoms were not clearly and explicitly recorded. Median age (p25-p75) at diagnosis was 68 years (25-75.3), predominantly manifesting with very late onset (n = 34; 54.8%) and in men (n = 38; 61.3%). AChR-ab were detected in 66.1% of patients (n = 41), with an initial mean titre of 11.3 in the 12 patients for whom this information was available. MuSK-ab determination yielded negative results in all patients. Among patients with seronegative MG (33.9%; n = 21), neuromuscular transmission alterations were confirmed by RNS in 76.2% of cases (n = 16) and by detection of abnormal jitter in 23.8% (n = 5). Median time to diagnosis of MG was one month (0-5). With regard to treatment, 82.3% of patients (n = 51) were receiving symptomatic treatment with pyridostigmine bromide at the time of analysis, and 74.2% (n = 46) were receiving at least one immunosuppressant drug, with prednisone being the most common (n = 41; 29 in monotherapy); other immunosuppressant drugs used included azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, and rituximab (n = 17). Median time to onset of corticosteroid treatment was 3.5 months (1-10.3). This treatment was associated with adverse reactions in 75.6% of patients, with the most frequent reactions including hyperglycaemia, osteoporotic fractures, and arterial hypertension. Six patients underwent thymectomy: 3 with thymoma and 3 with seropositive forms that had progressed to GMG. Treatment objectives were achieved in 85.5% of cases, with 37% presenting minimal, non-disabling symptoms and 53.2% achieving clinical remission (complete in 17.7% and pharmacological in 32.3%). Six patients (9.7%) died, with the main cause of death being MG in one and invasive thymoma in another.

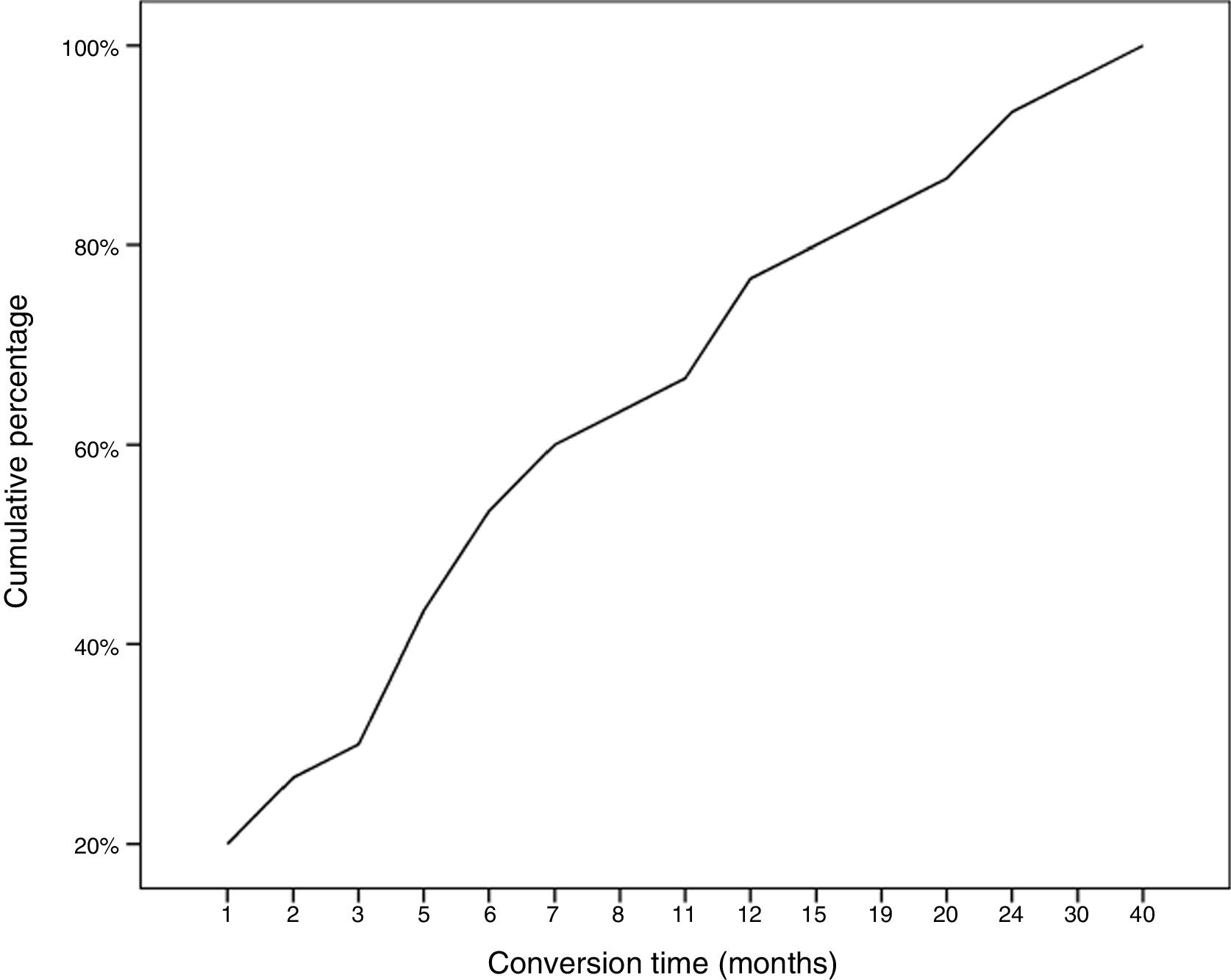

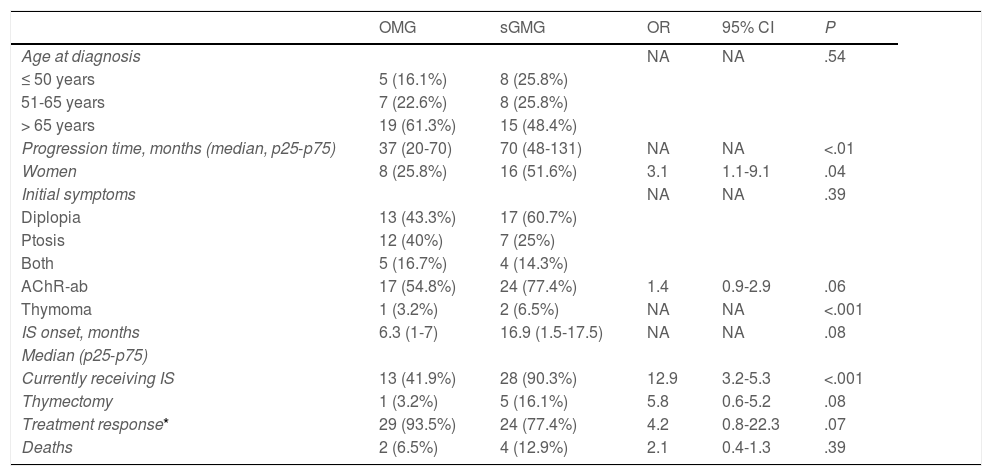

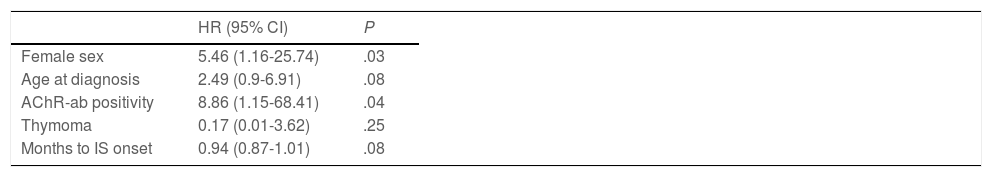

During follow-up, half of patients (n = 31) presented generalisation of MG, after a median of 6 months of progression (2-12.8). In all but 2 cases (6.6%), progression to GMG occurred during the first 24 months of disease progression (Fig. 1). Median follow-up time when the analysis was conducted was 54.5 months (3-720); 13 patients (20.9%) with exclusively ocular symptoms presented progression times shorter than 2 years. Table 2 shows the main demographic, clinical, serological, and prognostic variables in patients with OMG and patients who progressed to GMG. The GMG subgroup presented a predominance of women and seropositive forms; the proportion of patients with diplopia as the initial symptom and with age of onset < 65 years was higher than in patients with OMG. In this group, 25.8% of patients received immunosuppressive treatment (prednisone, n = 8) before generalisation, with a shorter median time to treatment onset than in patients with OMG (2 [1-7] vs 5 [1.5-17.5] months); however, this difference was not statistically significant. Treatment objectives, and particularly clinical remission, were less frequently achieved in patients with GMG, despite the greater proportion of patients in this group receiving immunosuppressive treatment. Finally, a logistic regression analysis including age, sex, AChR-ab positivity, presence of thymoma, and time to onset of corticotherapy (Table 3) identified significant associations with female sex (OR: 5.46; 95% CI, 1.16-25.74; P = .03) and with AChR-ab positivity (OR: 8.86; 95% CI, 1.15-68.41; P = .04).

Comparative analysis of the main demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors between patients with and without secondary generalisation of OMG.

| OMG | sGMG | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | NA | NA | .54 | ||

| ≤ 50 years | 5 (16.1%) | 8 (25.8%) | |||

| 51-65 years | 7 (22.6%) | 8 (25.8%) | |||

| > 65 years | 19 (61.3%) | 15 (48.4%) | |||

| Progression time, months (median, p25-p75) | 37 (20-70) | 70 (48-131) | NA | NA | <.01 |

| Women | 8 (25.8%) | 16 (51.6%) | 3.1 | 1.1-9.1 | .04 |

| Initial symptoms | NA | NA | .39 | ||

| Diplopia | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (60.7%) | |||

| Ptosis | 12 (40%) | 7 (25%) | |||

| Both | 5 (16.7%) | 4 (14.3%) | |||

| AChR-ab | 17 (54.8%) | 24 (77.4%) | 1.4 | 0.9-2.9 | .06 |

| Thymoma | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (6.5%) | NA | NA | <.001 |

| IS onset, months | 6.3 (1-7) | 16.9 (1.5-17.5) | NA | NA | .08 |

| Median (p25-p75) | |||||

| Currently receiving IS | 13 (41.9%) | 28 (90.3%) | 12.9 | 3.2-5.3 | <.001 |

| Thymectomy | 1 (3.2%) | 5 (16.1%) | 5.8 | 0.6-5.2 | .08 |

| Treatment response* | 29 (93.5%) | 24 (77.4%) | 4.2 | 0.8-22.3 | .07 |

| Deaths | 2 (6.5%) | 4 (12.9%) | 2.1 | 0.4-1.3 | .39 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AChR-ab: anti–acetylcholine receptor antibodies; IS: immunosuppressive treatment; NA: not applicable; OMG: ocular myasthenia gravis; sGMG: secondary generalisation of myasthenia gravis.

Multivariate analysis. Binary logistic regression analysis of variables associated with secondary generalisation of ocular myasthenia gravis.

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 5.46 (1.16-25.74) | .03 |

| Age at diagnosis | 2.49 (0.9-6.91) | .08 |

| AChR-ab positivity | 8.86 (1.15-68.41) | .04 |

| Thymoma | 0.17 (0.01-3.62) | .25 |

| Months to IS onset | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) | .08 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AChR-ab: anti–acetylcholine receptor antibodies; HR: hazard ratio; IS: immunosuppressive treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first Spanish series studying the clinical characteristics of and risk factors for secondary generalisation of OMG. This subtype, like MG in general, predominantly affects men, presents with very late onset, and is frequently associated with AChR-ab seropositivity.21

In one-third of the series of OMG published to date, as in our study, the likelihood of secondary progression to GMG is greater than 50%.10,14,17,18 One of the main factors explaining this high conversion rate is the inclusion of all patients who initially presented ocular symptoms, without taking into account the time to generalisation. Some authors argue that patients presenting exclusively ocular symptoms at onset and subsequently developing oropharyngeal, respiratory, and/or limb muscle involvement within the first 3 months of disease progression should be considered to have GMG rather than OMG.22 However, this temporal criterion is not included in the 2015 diagnostic criteria for OMG of the Myasthenia Gravis Association of America, which consider the presence of ptosis and/or diplopia at onset to be sufficient to establish this diagnosis.2

Early generalisation of OMG is interesting from both a clinical and a therapeutic perspective, as any treatment strategy (eg, immunosuppression and/or thymectomy) demonstrated to be able to prevent this conversion should be implemented as early as possible. To this end, we must seek to rapidly identify eligible patients, avoiding the diagnostic delay that frequently occurs with this disease. Regarding this point, another fundamental issue is the identification of patients with greater risk of generalisation, with a view to avoiding the indiscriminate use of immunosuppressive drugs. Wong et al.3 developed a scale to stratify this risk according to presence of AChR-ab, other autoimmune diseases, and thymic hyperplasia. However, according to the current evidence and our own results, despite their limitations, the only factor showing a consistent, reproducible association with generalisation is seropositivity for AChR-ab.3,5,7,10–14,16,18 In our series, patients with these antibodies presented 9 times greater risk of generalisation than those with seronegative forms. Other authors have reported a correlation between titres of these antibodies and risk of generalisation.11,14 MuSK-ab–associated OMG is a rarer form of the disease, with a high conversion rate.15,22–24 Women also seem to be at greater risk of generalisation (OR: 4.6). However, this association is only reported in one-fifth of studies.12,15,19 Similarly, only some studies have found MG generalisation to be significantly associated with thymic alterations,3,8,17,19,24 diplopia at onset,25 or abnormal RNS or single-fibre EMG findings18 (Fig. 1).

The association between age at diagnosis and the risk of MG generalisation merits special mention, as recent years have seen a considerable increase in the incidence and prevalence of MG in older populations,25 who are also more susceptible to developing complications due to long-term immunosuppression. Several authors report that advanced age is associated with greater risk of conversion.3,12,16,24 However, while the median age of onset in our series is older than those reported in other cohorts, the subgroup of patients with secondary GMG was younger than the remaining patients, although this difference was not significant. Similarly, Kamarajah et al.10 describe the natural history of OMG without mediation by the possible effect of immunosuppressive treatment; unlike other authors, they argue that early-onset forms present the greatest risk of generalisation.10 Therefore, the relationship between age and risk of generalisation continues to be controversial.

Finally, with respect to treatments to prevent generalisation, we did not observe differences in conversion rates between patients receiving corticosteroids after symptomatic treatment failure and those who did not require this treatment; however, we were surprised to observe that treatment onset was earlier in patients who did present generalisation. This suggests that greater symptom severity at onset and lack of response to pyridostigmine bromide are also associated with increased risk of generalisation.12 The first authors to propose the potential protective effect of corticosteroids were Kupersmith et al.,4 in 1996. In vitro studies had previously shown that exposure to dexamethasone attenuated the loss of acetylcholine receptors in muscle tissue after incubation with the serum of patients with MG.26 Since then, numerous retrospective studies have been conducted, without treatment guidelines defining precisely when treatment should be started, the initial and maintenance doses to be used, or populations at risk.27 The EPITOME trial, designed to analyse the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of prednisone in the treatment of OMG, failed to achieve this objective, as it was suspended due to recruitment issues.28 Therefore, we currently lack scientific evidence to recommend this treatment beyond the symptomatic control of OMG. With respect to thymectomy, a meta-analysis concluded that this procedure has a protective effect when it is performed early.29 In fact, the British management guidelines for MG recommend the intervention in patients with OMG presenting positivity for AChR-ab, no thymoma, and age under 40 years.30 However, this recommendation is not extended to the remaining international guidelines.

Both our study and previous research are affected by several limitations, including the observational and retrospective study design, differences in the inclusion criteria used due to the lack of a detailed definition of OMG and GMG, the small sample size, and the possible influence of immunosuppression. In the light of this, there is a need for prospective studies to identify the patients at greatest risk of MG generalisation and clinical trials to assess the potential benefit of immunosuppressive treatment and thymectomy in these patients.

In conclusion, identifying OMG associated with AChR-ab is highly important, as seropositivity for these antibodies is the main risk factor for conversion to GMG. Clarifying the role of such other potential risk factors as age, sex, and thymic alterations may enable us to identify patients eligible for trials studying the effect of an early preventive treatment, and constitutes a clinical challenge in the field of MG.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.