Epilepsy is one of the most frequently observed diseases in neurology outpatient care.

MethodsWe analysed our hospital's implementation of the 8 epilepsy quality measures proposed by the American Academy of Neurology: documented seizure types and seizure frequency, aetiology of epilepsy or the epilepsy syndrome, review of EEG, MRI, or CT results, counselling about antiepileptic drug side effects, surgical therapy referral for intractable epilepsy, and counselling about epilepsy-specific safety issues and for women of childbearing age.

ResultsIn most cases, the first four quality measures were documented correctly. In 66% of the cases, doctors had asked about any adverse drug effects during every visit. Almost all patients with intractable epilepsy had been informed about surgical options or referred to a surgical centre of reference for an evaluation at some point, although referrals usually took place more than 3 years after the initial proposal. Safety issues had been explained to 37% of the patients and less than half of the women of childbearing age with epilepsy had received counselling regarding contraception and pregnancy at least once a year.

ConclusionsThe care we provide is appropriate according to many of the quality measures, but we must deliver more counselling and information necessary for the care of epileptic patients in different stages of life.

La epilepsia es una de las afecciones que con más frecuencia atendemos en las consultas externas de neurología.

MétodosAnalizamos la aplicación en nuestro centro de las 8 medidas sobre calidad en el cuidado de pacientes con epilepsia propuestas por la Academia Americana de Neurología: tipo de crisis y frecuencia de crisis, etiología de la epilepsia o síndrome epiléptico, resultados electroencefalograma, neuroimagen, aconsejar sobre efectos adversos de los fármacos antiepilépticos, remisión de los casos de epilepsia refractaria, consejos sobre cuestiones de seguridad y a mujeres en edad fértil.

ResultadosEn la mayoría de los casos estaba documentado adecuadamente las 4 primeras medidas de calidad. En el 66% se había preguntado sobre efectos adversos de los fármacos en todas las visitas. En casi todas las epilepsias intratables se había propuesto o remitido a un centro de referencia quirúrgico para la valoración en algún momento de la enfermedad, aunque generalmente hacía más de 3 años de la propuesta. Un 37% de los pacientes habían sido aconsejados sobre cuestiones de seguridad y menos de la mitad de las mujeres con epilepsia en edad fértil habían recibido consejos relativos a anticonceptivos y embarazo al menos una vez al año.

ConclusionesRealizamos una atención adecuada de acuerdo con las medidas de calidad en muchos de los aspectos clínicos, pero debemos mejorar la administración de consejos e información necesaria para el cuidado del paciente con epilepsia en las diferentes etapas de la vida.

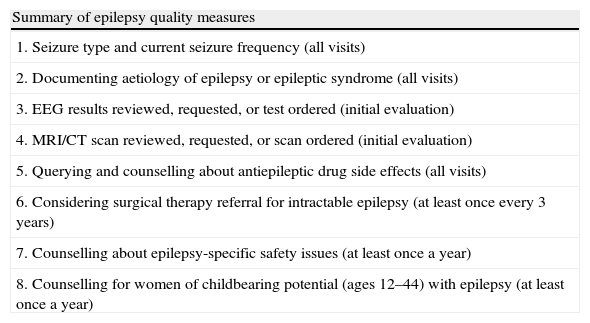

Epilepsy is a neurological disease which affects nearly 50 million people in the world and almost 6 million people in Europe.1–3 However, this disease is often incorrectly diagnosed or inappropriately treated. The American Academy of Neurology (ANN), as on previous occasions with other neurological diseases like stroke4 or Parkinson's disease,5 has published a collection of performance measures for doctors who treat patients with epilepsy.6 Out of all the measures studied, 8 were considered relevant to epilepsy patient care: (1) seizure type and frequency; (2) aetiology of epilepsy or epileptic syndrome; (3) EEG results; (4) neuroimaging study; (5) counselling about antiepileptic drug side effects; (6) considering a surgical referral for patients with refractory epilepsy; (7) counselling about epilepsy-specific safety issues; and (8) advice to women of childbearing potential on pregnancy and contraception (Table 1). The purpose of our study was to determine whether our hospital's outpatient neurology service was providing care to epilepsy patients according to quality standards.

Summary of epilepsy quality measures (AAN).a

| Summary of epilepsy quality measures |

| 1. Seizure type and current seizure frequency (all visits) |

| 2. Documenting aetiology of epilepsy or epileptic syndrome (all visits) |

| 3. EEG results reviewed, requested, or test ordered (initial evaluation) |

| 4. MRI/CT scan reviewed, requested, or scan ordered (initial evaluation) |

| 5. Querying and counselling about antiepileptic drug side effects (all visits) |

| 6. Considering surgical therapy referral for intractable epilepsy (at least once every 3 years) |

| 7. Counselling about epilepsy-specific safety issues (at least once a year) |

| 8. Counselling for women of childbearing potential (ages 12–44) with epilepsy (at least once a year) |

AAN: American Academy of Neurology; EEG: electroencephalogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography.

This retrospective observational study analysed 100 medical histories from our outpatient neurology department. These histories, consecutively recorded in our database, listed a diagnosis of epilepsy and corresponded to patients who had been followed for at least one year in our district hospital (located in a southern suburb of Madrid and providing care to a population of 150000 inhabitants). In our analysis, we recorded to what extent the AAN's proposed quality measures were applied to epilepsy patient care across all visits to our outpatient service. Data on demographic variables (age, sex), clinical variables (duration of epilepsy, response to medication) and the 8 quality measures previously described were collected.7 The study was approved by the research committee at our hospital.

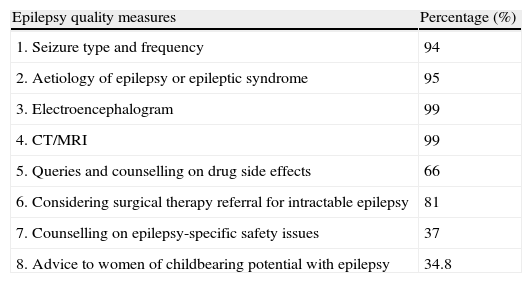

ResultsThe mean age of patients was 37.2 years (range, 15–81 years) and 55% were male. Median epilepsy duration was 10.5 years (range, 2–50 years); 65% of the patients were treated with monotherapy and 35% with polytherapy. Broken down by response to epilepsy medication,8 65% responded to treatment, response was undefined in 22%, and 13% had drug-resistant epilepsy. Regarding the first measure, seizure type and the frequency of each type were entered in the medical record on all visits in 94% of the patients. For the second measure, aetiology of epilepsy or epileptic syndrome was recorded on all the visits in 95% of the patients. For the third measure, electroencephalogram was requested or reviewed in the initial evaluation in 99% of the patients. Regarding the fourth measure, a CT and/or MRI scan was either ordered or reviewed in the initial evaluation in 99% of the patients. The fifth measure, regarding querying and counselling on antiepileptic drug side effects, was recorded for all visits in 66% of the patient total, in more than three-quarters of the visits in 6%, in half of the visits in 28%, and in less than a quarter of the visits in 2% of the patients. Exclusion criteria were present in 6% of our patients. The sixth measure refers to considering surgical treatment for intractable epilepsy and documenting it in the patient's medical history at least every 3 years. Surgical therapy had been suggested to 81% of the patients with intractable epilepsy and some of them had been referred to a epilepsy surgery centre for assessment after being diagnosed with the disease. In most patients, however, this option had been suggested more than 3 years before. For the seventh measure, on counselling about epilepsy-specific safety issues, 37% of the cases were informed at least once a year, 17% of the cases less than once a year, and 46% of the cases never received counselling. The eighth and last measure addresses counselling for women of childbearing potential (12–44 years) on pregnancy and contraception; 34.8% of the patients were informed at least once a year, 8.7% of the patients were informed less than once a year, 52.2% of the patients were never counselled, and 4.3% met exclusion criteria (surgically sterile) (Table 2).

Results for epilepsy quality measures.

| Epilepsy quality measures | Percentage (%) |

| 1. Seizure type and frequency | 94 |

| 2. Aetiology of epilepsy or epileptic syndrome | 95 |

| 3. Electroencephalogram | 99 |

| 4. CT/MRI | 99 |

| 5. Queries and counselling on drug side effects | 66 |

| 6. Considering surgical therapy referral for intractable epilepsy | 81 |

| 7. Counselling on epilepsy-specific safety issues | 37 |

| 8. Advice to women of childbearing potential with epilepsy | 34.8 |

We compared our results with data from a study based on a survey directed at neurologists in Michigan (USA).9 The survey included questions on these 8 quality measures. Most doctors adhered to these quality measures referring to seizure type and frequency (83%), EEG review (84%), and MRI (90%). However, only 59% recorded the aetiology of the epileptic syndrome for each patient on each visit. Only 37% of the doctors surveyed provided counselling about antiepileptic drug side effects on every visit, compared to 66% in our study. Only 26% of these respondents considered a surgery referral every 3 years; although the percentage of referrals in our case was higher at 81%, the frequency of referral for a surgical evaluation generally exceeded 3 years. Regarding epilepsy-specific safety issues, 49% of the respondents counselled patients on every visit while 21% did so at least once yearly. This percentage is significantly higher than the one provided by our records. Most of the doctors surveyed (94%) offered counselling to women of childbearing potential, in contrast to our study, in which less than half the patients were informed at least once a year.

We should highlight that the studies used different methods and were performed in different health systems. Our study only included data related to the measures that were recorded as such in the medical records. The other study analyses responses to survey questions (14% response rate). One of our study's limitations is that it only considers data written in the medical histories, but in normal clinical practice not everything commented during the visit is recorded.

In conclusion, care seems to be delivered in accordance with quality measures for many clinical parameters. As in other studies, one of the most controversial subjects is when clinicians should refer patients to epilepsy surgery centres. These studies show that the quality measure of assessing this possibility every 3 years is not met in most cases.10–12 In our study, 13% of the patients presented drug-resistant epilepsy. Among the medical histories of intractable epilepsy cases, 81% mentioned the possibility of surgery or documented a referral for surgical evaluation at some point during the disease. In general, evaluations had been suggested more than 3 years previously and we did not analyse the number of patients who were finally referred and assessed. An evaluation frequency of 3 years may be excessive for our setting. Performance measures related to counselling about side effects or daily life issues must be improved. It is essential that doctors counsel patients on safety in the specific context of patient's age, seizure type and frequency, occupation, and leisure activities (for example, how to prevent injuries or if driving restrictions are recommended), etc. Women of childbearing potential should be informed on how epilepsy and antiepileptic drugs may affect pregnancy and the effectiveness of contraceptives.13–15 We should not forget that social, family, and work conditions change throughout the patient's lifetime, and it is therefore essential to provide updated information in a timely manner.

The suitability of the AAN's quality measures for studies in our setting is debatable; it is possible that other structural measures should be used instead given the differences between the two healthcare systems. However, these measures can serve as guidelines for appropriate care at all care levels. These quality measures can help us avoid rigid routine management of visits and provide more systematic comprehensive care, not only in terms of clinical symptoms and diagnostic tests but also for matters that affect patient's quality of life. Quality measures do not specifically analyse the information provided to the patient; instead, they analyse whether the patient receives advice on specific topics. It may be necessary to specify the minimum information that should be provided, for example, counselling about driving limitations.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to provide information on the fulfilment of quality standards for epilepsy care in a neurology outpatient service in our setting. Our results are comparable to those obtained in similar English-language studies for most of the study items.9

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de la Morena Vicente MA, Ballesteros Plaza L, Martín García H, Vidal Díaz B, Anaya Caravaca B, Pérez Martínez DA. Medidas de calidad en la atención a pacientes con epilepsia en la consulta de neurología. Neurología. 2014;29:267–270.

Part of this study was presented at the 63rd annual meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, Barcelona, November 2011.