Anti–glutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD) autoantibodies are associated with a series of different neurological disorders. Although their association with stiff-person syndrome (SPS), cerebellar ataxia, and autoimmune epilepsy is well known, the full spectrum of symptoms remains uncertain, and has been related to such other conditions as limbic encephalitis and cognitive impairment.

We describe the clinical progression of a patient with cerebellar ataxia associated with anti-GAD antibodies who, after remaining stable for several years,1 presented symptoms of SPS and rapidly progressive cognitive impairment.

Our patient was a 65-year-old woman with diabetes who developed subacute cerebellar ataxia at the age of 50 years. An extensive study including a radioimmunoassay revealed high titres of anti-GAD antibodies in the blood (23 000 U/mL); these results were subsequently confirmed by an immunoblot study. After ruling out other potential causes of cerebellar involvement, we diagnosed anti-GAD antibody–associated ataxia, which was treated with low doses of prednisone and azathioprine. With this treatment, the patient remained clinically stable until the age of 61 years, when ataxia progressed and she began to develop symptoms of SPS. The patient then started treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) at 0.4 mg/kg/day for 5 days, achieving partial improvement of SPS but not of ataxia.

By the end of that year, her husband began to report occasional episodes of confusion and disorientation, which became more pronounced in the following months. The patient scored 18/29 on the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) at that time, with impairment predominantly affecting orientation in time and memory. Blood analysis ruled out other possible causes of dementia, with the exception of the continued presence of anti-GAD antibodies. A waking EEG revealed diffuse slowing of brain activity, with no epileptic activity.

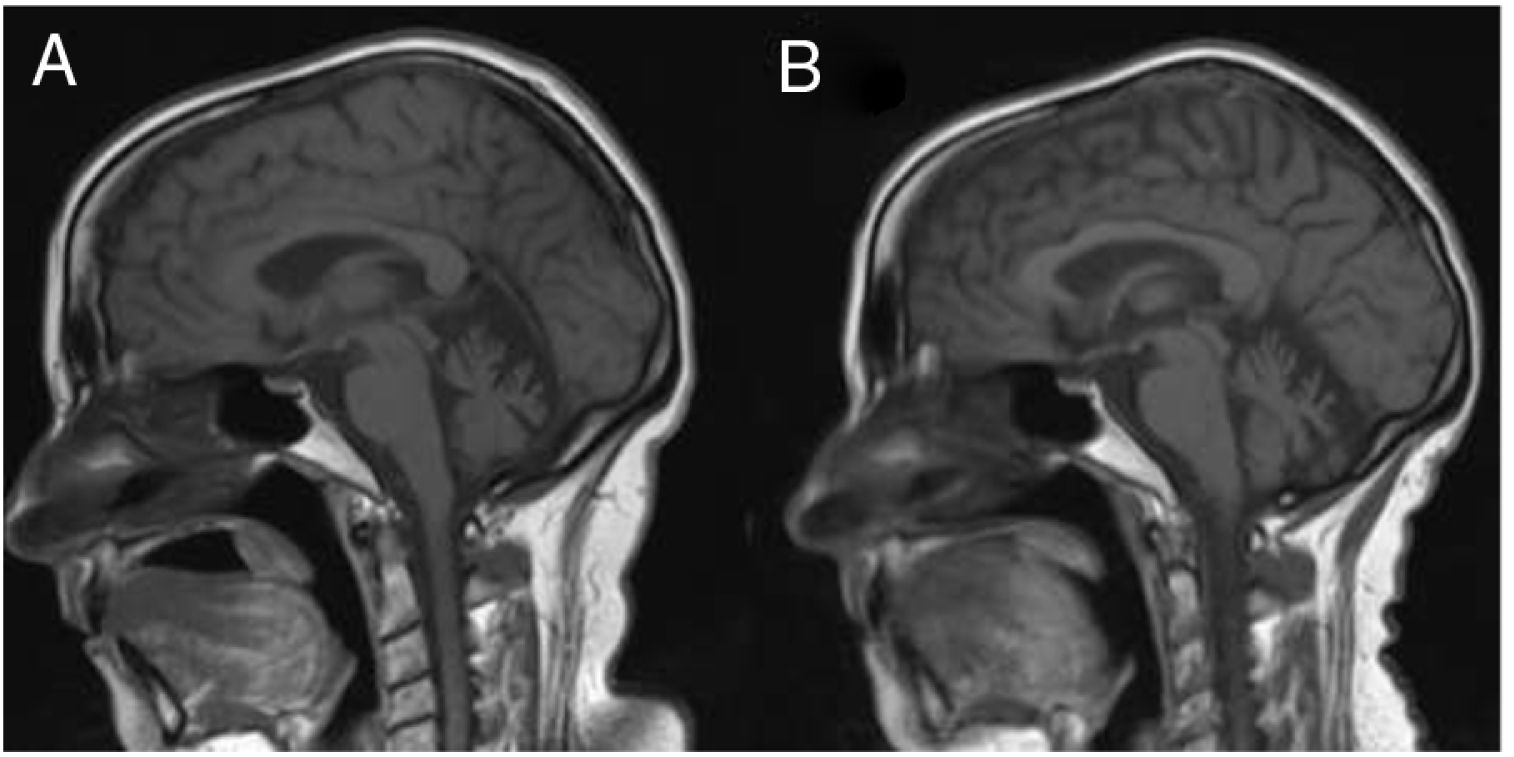

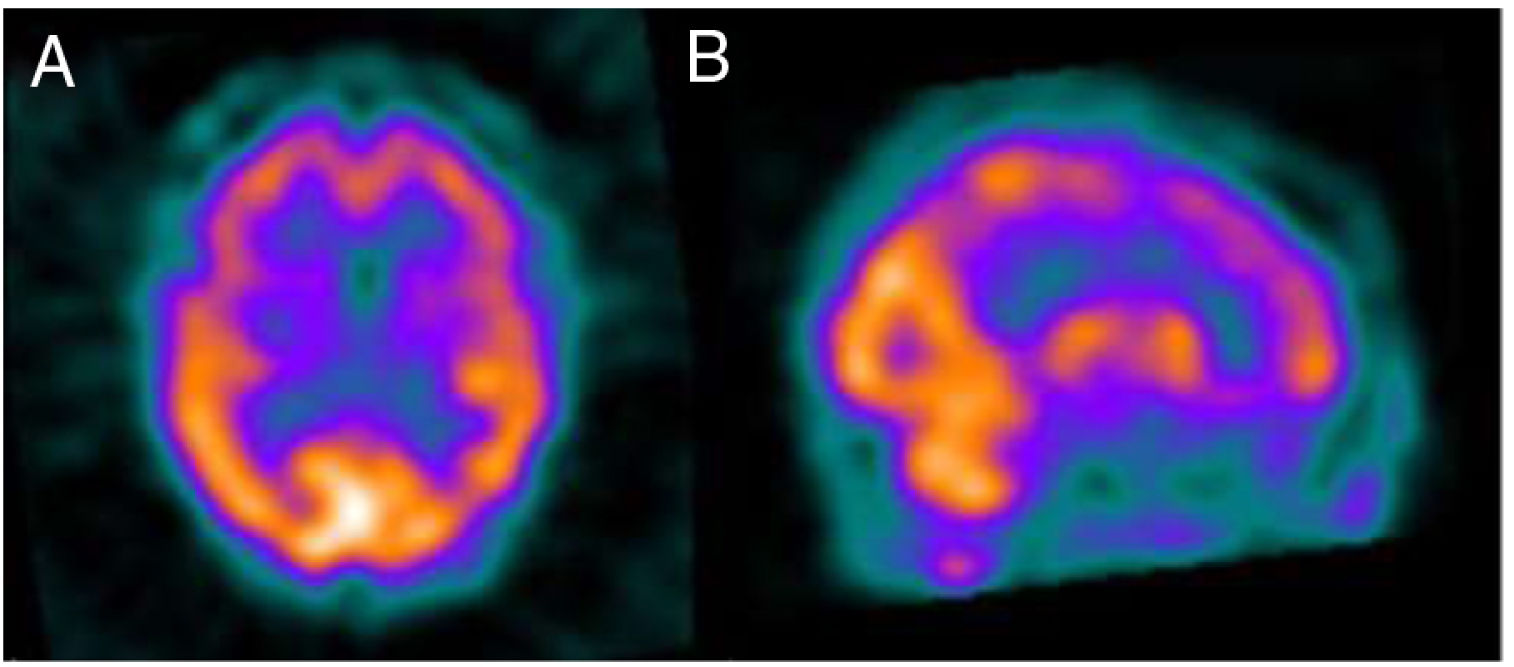

Several months later, the patient was unable to remember dates and mixed up family members, and her husband progressively took responsibility for almost all instrumental activities. A follow-up MRI study (Fig. 1) revealed significant atrophy of the vermis and, to a lesser degree, of the cerebellar hemispheres, with no other alterations. A brain 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT study revealed bilateral frontal and left temporal and parietal hypoperfusion, findings compatible with frontotemporal dementia (Fig. 2). The patient and her family refused a lumbar puncture.

Sagittal slice from a T1-weighted brain MRI sequence performed at symptom onset (A) and at 3 years of progression (B). A) Cerebellar atrophy is observed, predominantly in the vermis. B) Increased cerebellar atrophy and mild prominence of cerebral sulci, predominantly in the perisylvian region.

We decided to administer a second cycle of IVIG at the same dose, which was repeated at one month, achieving no clinical improvement. Cognitive impairment continued progressing in the following months, and a comprehensive neuropsychological study showed severe frontotemporal dementia. At the age of 63 years, one year and a half after the onset of impairment, she scored 9/30 on the MMSE. We ruled out more aggressive immunomodulatory treatments.

The clinical spectrum of anti-GAD syndrome is still being reviewed.2,3 Very few publications have analysed the presence of cognitive impairment in patients with anti-GAD antibodies, although the current evidence seems to support an association between both entities.4,5 An isolated case report of cognitive impairment associated with anti-GAD antibodies describes a similar clinical profile to that observed in our patient, with no response to IVIG treatment.6 The decision to start treatment with aggressive immunomodulatory treatments in these patients should be made with caution, taking into account each patient’s personal situation and the variable response of other anti-GAD–associated syndromes such as cerebellar ataxia. Furthermore, the sequential onset of cerebellar ataxia, SPS, and rapidly progressive cognitive impairment in the same patient demonstrates symptom overlap, with different symptoms coexisting and manifesting asynchronously. Our study lacks data from monitoring of the antibody titres throughout disease progression. However, future studies may provide evidence on whether variations in antibody titres may be related to the onset of new symptoms.

With this publication, we aim to contribute to the understanding of the clinical spectrum of anti-GAD–associated syndromes. Cognitive impairment may be part of the spectrum of associated clinical manifestations, and a low level of suspicion may delay diagnosis and the chance to start or intensify treatment in early stages of impairment.

Please cite this article as: Martin Prieto J, Rouco Axpe I, Moreno Estébanez A, Rodríguez-Antigüedad Zarrantz A. Demencia rápidamente progresiva asociada a anticuerpos anti-carboxilasa del ácido glutámico: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2022;37:151–152.