Tethered spinal cord syndrome is a congenital anomaly resulting from abnormal development of the neuraxis, in which the medullary cone is fixed at a level lower than normal.1 It can be produced by different pathological entities such as the thickening of the filum terminale, intradural lipomas, diastematomyelia, dermal sinus fibre tracts, and sacral dysgenesis and acquired pathologies such as secondary adhesions to the closure of myelomeningocele.2 Clinically, it is characterised by neurological symptoms, urogenital dysfunction and orthopaedic sequelae. It is usually diagnosed in childhood, but it sometimes remains asymptomatic until adulthood.3 The symptoms can appear either spontaneously or after triggered by a trauma. Presentation with isolated urological dysfunction is very rare.4

A 43-year-old male presented with a personal history of migraine without aura and gastric dyspepsia with a normal panendoscopy. He did not present a family history of neurological or urological disorders. He referred to fatigue symptoms that evolved over several months, and in the blood test his GP had performed, he was found to have renal failure with normal potassium levels (urea 186mg/dl, creatinine 5.7mg/dl). He presented problems on urinating of a least 6 months’ evolution. He had no sensory motor deficit, back pain, sexual dysfunction, amyotrophy or skin or orthopaedic disorders.

The general examination with heart and lung auscultation was normal. Abdomen with distended bladder. No cutaneous stigmata from congenital defects. Lower limbs with no pathological findings. Neurological examination: normal cortical functions and cranial nerves. Motor: symmetric and conserved tone and strength. Symmetric stretch reflexes +++/++++. Plantar cutaneous flexor reflexes. Sensitivity, cerebellum and walk, with no changes.

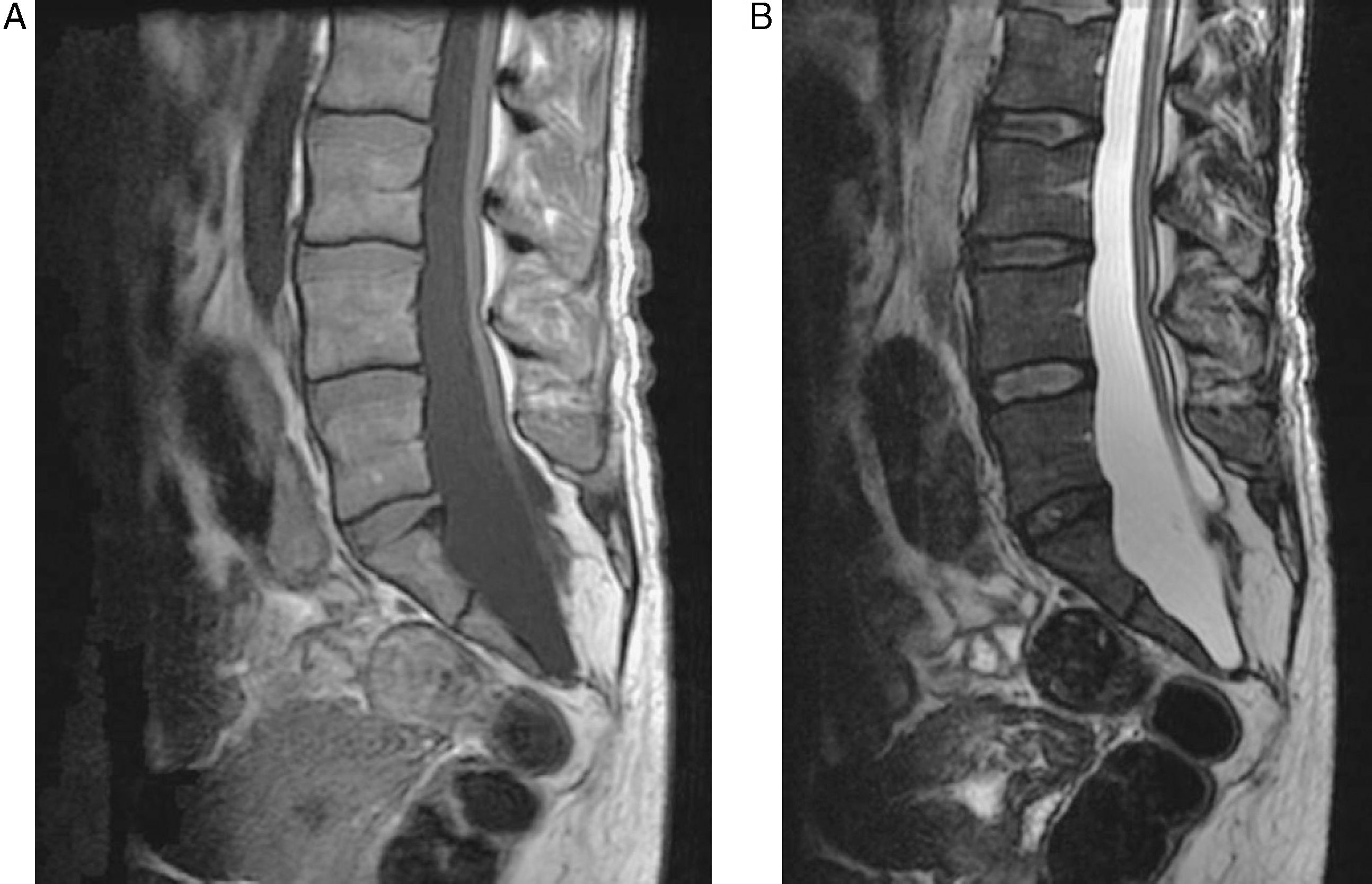

Blood count, coagulation, vitamin B12, folic acid, anti-nuclear antibodies, liver enzymes, thyroid hormones, rheumatic tests and serum protein with no significant changes. Abdominal ultrasound: kidneys with grade III bilateral hydronephrosis with cortical thinning, predominantly on the left side with no cause for filial obstructive. Antegrade pyelography: permeable urinary tract. Lumbosacral radiography: sacral dysgenesis. Urodynamic study: detrusor hyperreflexia and urethral sphincter dyssynergia compatible with neurogenic bladder. Lumbosacral magnetic resonance (Fig. 1): meningocele with tethered cord, terminal lipoma and posterior sacral dysraphism.

The patient received treatment with oxybutynin 2.5mg each 8h. A right nephrostomy was also carried out, with a gradual decline of creatinine, although the levels were still raised when he was discharged (2.4mg/dl). The neurosurgical team suggested lipoma excision surgery and untethering the spinal cord, but this was rejected by the patient because of a lack of guarantees that the surgery would be successful. As well as his treatment with oxybutynin, the patient had self-catheterisations as an out-patient. We have not been able to follow-up the patient, as he did not return to successive revisions.

Sagittal magnetic resonance of the thoracolumbar spine is the technique of choice to diagnose tethered spinal cord syndrome.5 The presence of a thickened filum terminale with a diameter greater than 2mm and/or a conus medullaris located below the L1–L2 has been established as radiological diagnostic criteria, and these should be accompanied by symptoms for a definitive diagnosis.

In cases where it seems no trauma was triggered, it has been postulated that neck flexion and extension movements over years would produce a movement towards the top of the spinal cord and this is the most damaged part of the conus medullaris.6 The physiopathological mechanisms involved were impairment of microcirculation and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism.7

Spinal cord malformations frequently coexist with vertebral anomalies. This leads to postulating the existence of a pluripotential caudal eminence whose disturbance or deficiency would provoke the different anomalies, or even an alteration of the mesoderm from which these organs derive.

Whilst children tend to consult for orthopaedic problems, in adulthood neurological and urological manifestations are the most frequent. In a case study review undertaken in our country, urological disorders accounted for three-quarters of referrals to the neurosurgeon for tethered cord syndrome.8 Bladder dysfunction in tethered cord syndrome varies between 40% and 93% in cases,9 which can manifest itself as incontinence-urgency or stress incontinence (87.5%), difficulty in urinating (40%), feeling of incomplete emptying (33%) or pollakiuria (33%). With regard to the urodynamic pattern, there are differences between authors, although it seems that the most common is bladder hyperreflexia.8

The treatment for tethered cord syndrome is controversial because it mainly improves sensory motor deficits and pain. Some authors advocate spinal release after diagnosis, thus preventing the progression of neurological dysfunction. Other authors note that the initial improvements are due to post-surgical denervation, especially in cases of hypertonia and hyperreflexia returning to baseline at 6 months, or that all the treatment does is stabilise the neurological deficit and does not give back normal functioning. The improvement percentage in urological disorders varies in different series, with results around 25%.10 The time from the onset of the symptoms to that of surgery is an important factor for prognosis.8,10

The differential diagnosis of tethered cord syndrome starting in adulthood is vast and is made up of different myelopathies, whether deficiency, inflammatory, cancerous or from multiple sclerosis. The presence of bone malformations in lumbosacral radiography can be present in up to 100% of cases in some series.8 That is why this technique should be carried out in cases of neurological dysfunction, as the presence of bone anomalies steers us towards tethered cord syndrome and would indicate that we should undertake magnetic resonance studies to confirm the diagnosis.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez Caballero PE. Insuficiencia renal como debut de un síndrome de médula anclada en el adulto. Neurología. 2011;26:566–8.