Chronic pain affects 17.25% of Spanish adults, and is frequently associated with such other comorbidities as anxiety (40.62%), depression (24.43%), and cardiovascular or gastrointestinal dysfunction.1 Many patients presenting persistent pain with no clear biological basis are diagnosed with somatic symptom disorder (SSD) and, after being assessed by different specialists, are referred to the neurology department for comprehensive evaluation.

Somatic symptoms have traditionally been studied from the perspective of psychiatry; however, physicians of all specialties should be familiar with these symptoms, given their increasing prevalence. The DSM-5 differentiates between SSD with predominantly somatic symptoms and SSD with predominant pain. SSD is characterised by “excessive thoughts, feelings, and behaviours related to the somatic symptom or associated health concerns.”2 In most cases, clinicians are unable to objectively evaluate the symptoms reported by the patient, which places us in the difficult position of having to assess the veracity of the patient’s claims.3 It is therefore important to be familiar with examination techniques that may assist us in differentiating between organic or functional damage and non-organic somatic symptoms.4 We present the case of a patient initially diagnosed with SSD and depression, who was subsequently diagnosed with anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES). The patient gave written informed consent for the publication of his case.

Case reportOur patient was a 37-year-old Spanish man with generalised abdominal pain, which was more intense in the right periumbilical region, and a 5-month history of tiredness appearing upon awakening, accompanied by dyspnoea and marked asthenia, which prevented him from working. He was evaluated by the internal medicine department, presenting a cortisol level of 4.89 µg/mL (normal range: 5.0–17.9), which normalised after administration of ACTH. Hydrocortisone dosed at 5 mg/day improved asthenia, but abdominal pain and the sensation of tiredness persisted. Three months later, the patient was referred to a mental health centre, where he was diagnosed with depression; he was prescribed mirtazapine dosed at 30 mg/day, with mood improving within a month. He was also referred to the gastroenterology and endocrinology departments due to persistent abdominal pain; no intestinal alterations were detected, despite suspicion of irritable bowel syndrome, which was ruled out. An MRI scan of the pituitary gland and additional hormone tests ruled out an endocrine disorder. The patient was finally referred to the neurology department. An abdomen and pelvis CT scan revealed no alterations, but the physical examination revealed positive Carnett sign, which made us suspect ACNES. We opted for ultrasound-guided anaesthetic nerve block, injecting 1% lidocaine into the trigger points of the anterior cutaneous nerve; this considerably reduced abdominal pain. An additional session of anaesthetic infiltration performed the following week resulted in complete symptom resolution. The patient continues to be asymptomatic 7 months later; psychoactive drugs have been withdrawn and his life has returned to normal.

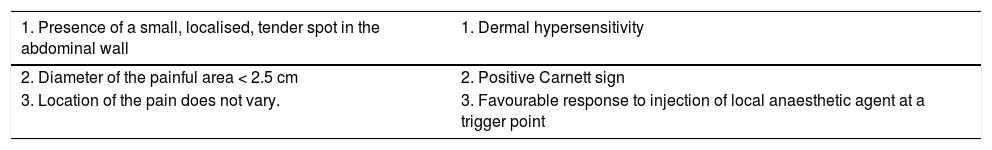

DiscussionACNES is a little-known syndrome that causes chronic abdominal pain in the ventral region; although its incidence is unknown, it has been estimated at 1 case per 2000 patients.5 Pain affects the terminal branches of intercostal nerves 8–12, which are entrapped through the abdominal muscles, causing chronic neuropathic pain that is difficult to diagnose. Due to the lack of complementary tests or a standardised physical examination for diagnosing ACNES,6 many of these patients are diagnosed with SSD and referred to multiple specialists, which may delay diagnosis for months or even years.7 Antidepressants are not effective as the source of the pain in ACNES is mechanical. However, a useful set of diagnostic criteria has been proposed (Table 1) for diagnosing ACNES in patients with normal CT/MRI findings and no signs of local cutaneous inflammation or infection. The Carnett test, described in 1926,8,9 is used to elicit the pain associated with anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment; the test is very useful for differentiating between somatic and visceral abdominal pain. During the test, the patient is asked to lie down and point to the painful area. The clinician then presses the most painful spot with one finger while the patient flexes the hip or raises the trunk. If pain worsens, the Carnett sign is positive. Response to anaesthetic nerve block is also diagnostic of ACNES, and the effects of this treatment may last for years.10 Such pain modulators as pregabalin and amitriptyline may help manage the associated pain; refractory patients may undergo neurectomy following exploratory surgery.11 In conclusion, differentiating between SSD and ACNES may be difficult. It is essential to perform the Carnett test in these cases; all specialists, and not only neurologists, should be familiar with this manoeuvre.

Diagnostic criteria for anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome.

| 1. Presence of a small, localised, tender spot in the abdominal wall | 1. Dermal hypersensitivity |

|---|---|

| 2. Diameter of the painful area < 2.5 cm | 2. Positive Carnett sign |

| 3. Location of the pain does not vary. | 3. Favourable response to injection of local anaesthetic agent at a trigger point |

Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome is diagnosed when the patient meets at least one criterion from each column.

Please cite this article as: García-Carmona JA and Sánchez-Lucas J. Papel de la maniobra de Carnett en el diagnóstico de un síndrome por atrapamiento del nervio cutáneo anterior confundido con un trastorno por síntomas somáticos: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2021;36:179–180.