The interesting study by Lago et al.1 transmits an important message: technological advances do not always represent an absolute improvement, since decreased mortality in the second period is cancelled out by an increase in dependence (mRS >3 in 13.3% of patients in the first stage vs 21.3% in the second stage) for patients with very similar severity and age, which are 2 key factors in determining outcome.2

Hospital mortality may not be the best indicator of healthcare quality; comparing therapeutic mortality associated with embolisation or surgery may lead us to mistakenly believe that surgery involves a higher mortality. Although there are very varied examples in the literature, we find no differences between the 2 periods, 1993–97 (no endovascular treatment) and 2008–2012 (when endovascular treatment was fully established).3 Lagares et al.4 have pointed to the variability in Spain regarding the use of guidelines for selecting the type of endovascular or surgical treatment; however, the type of treatment chosen did not have an impact on final progression. Furthermore, Horcajadas Almansa et al.5 report that endovascular treatment is more costly than surgery for ruptured aneurysms, basically due to the price of embolisation materials, the rate of retreatment, and the necessary follow-up.

In specific cases, combined treatments with embolisation and surgery in a hybrid operating room (Fig. 1) may be a good therapeutic option; this way, neurosurgeons, who were previously the only specialists dedicated to aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH), may contribute to improving outcomes. Furthermore, the different specialists involved (neurosurgeons, neurologists, neuroradiologists) should be trained in endovascular treatment during residency; failure to provide this training will result in decreases in the number of trained/interested neurosurgeons, with only very difficult/complex cases considered by specialists as “bad” cases being treated surgically (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the industry advances rapidly and endeavours to find new materials for every situation, regardless of size, location, and dome-to-neck ratio. However, as with surgery, we should ask ourselves more frequently whether a determined aneurysm should be treated because it is possible or because it is necessary.

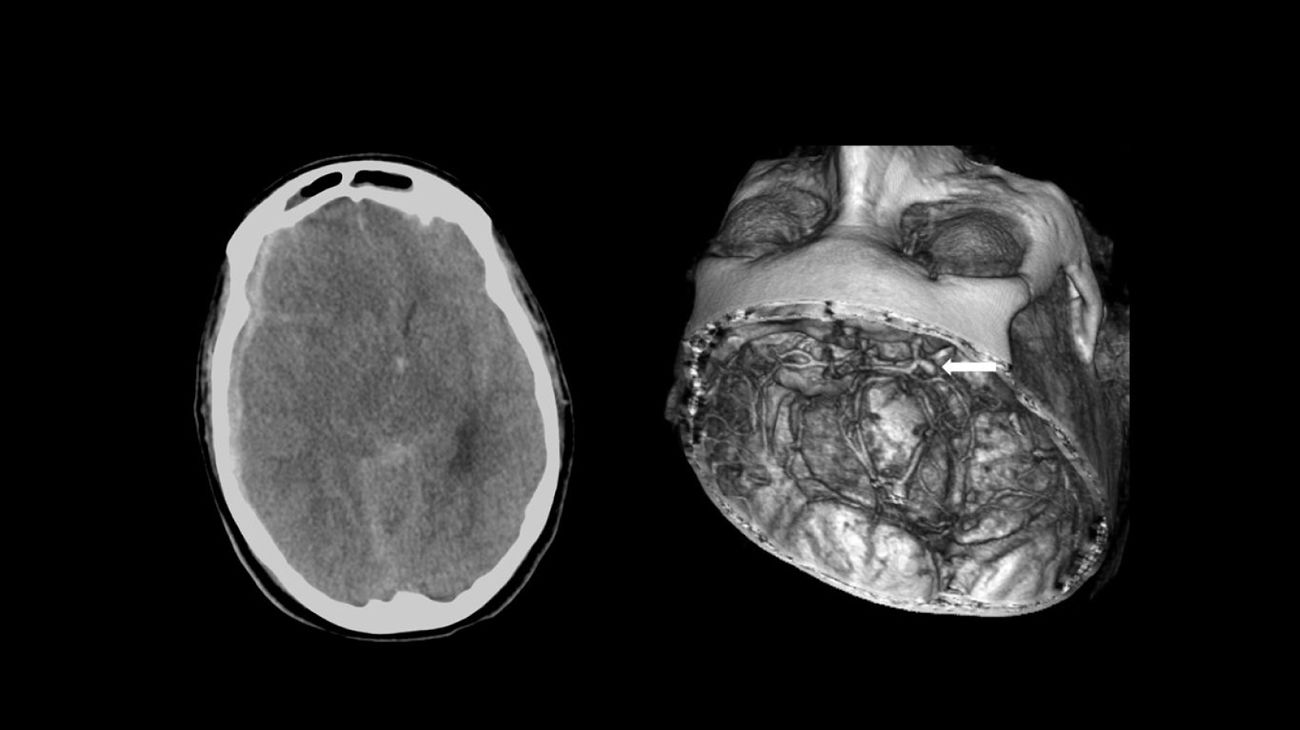

Fifty-three-year-old woman who presented sudden headache with loss of consciousness. Emergency services intubated the patient and transferred her to hospital, where she was diagnosed with SAH with acute subdural haematoma caused by a ruptured aneurysm in the posterior communicating artery (arrow). She was transferred to another hospital with a weekend on-call service for SAH; a craniectomy was performed to evacuate the acute subdural haematoma and subsequent aneurysmal embolisation. The patient died 13 days later.

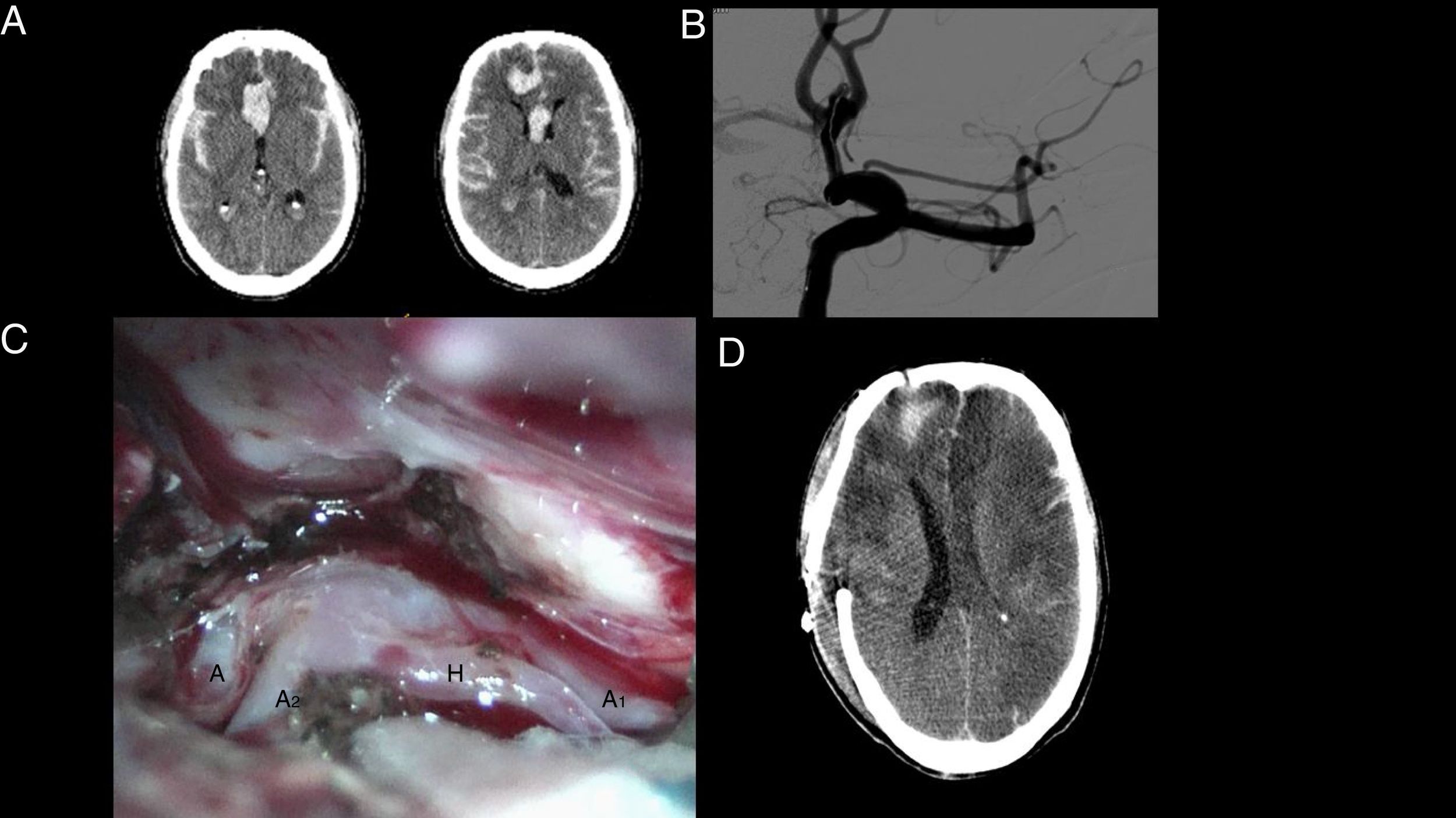

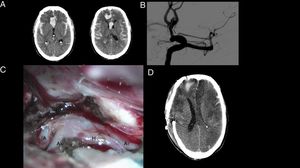

Sixty-two-year-old man presenting SAH with headache and loss of consciousness. Emergency services performed orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation and the patient was transferred to hospital for a CT scan. The patient was referred from the first hospital to a centre with a weekend on-call service for SAH where a second CT scan was performed (A), revealing an increased amount of blood (rebleeding). Endovascular treatment was attempted, and although the microcatheter could be inserted into the aneurysm (B), endovascular treatment was eventually ruled out. Emergency clipping of the aneurysm was performed (C). A CT scan performed several days later revealed multiple bilateral infarcts (D), suggestive of vasospasm. The patient died 20 days after admission.

I have previously expressed my opinion regarding some organisational aspects of stroke treatment6 and the obvious benefits of a multidisciplinary approach. However, only the specialist attending the patient in the emergency department, studying the CT scan and multimodal CT scan, can reconstruct images at a workstation and observe the characteristics of the aneurysm and its relation with other anatomical structures in order to decide the best approach for the patient (endovascular, surgical, or combined therapy [Fig. 1]), especially when he/she performs both techniques. Some surgeries can be performed with acceptable results using only CT angiography images, with no need for a preoperative angiography.7 In light of this, I think it interesting that Lago et al.1 report that emergency angiography for aSAH has been performed since 2014; however, we can deduce that treatment is not performed at the same time as the emergency diagnostic angiography. The multimodal CT scan used for ischaemic stroke should also be utilised to analyse some anatomical and physiological aspects of aSAH. I fail to understand why in some hospitals with on-call services for ischaemic stroke, the information provided by CT perfusion is not used for aSAH; some aneurysms might be treated more efficiently with surgery.

The consensus document8 prepared by the societies of neurology, neurosurgery, neuroradiology, and the Spanish Group of Interventional Neuroradiology for training/accreditation in interventional neuroradiology represents a milestone in the history of neurosciences. The next step is probably to prepare another consensus document for vascular neurosurgeons, an endangered specialty, to obtain certified accreditation to perform bypasses, remove arteriovenous malformations, and (if copayment is established) to clip aneurysms, due to the high cost of embolisation materials for families with limited resources. The vascular neurosurgeon may first become an ornamental professional, an expert in clipping and bypass, mentioned on large hospitals’ websites. Regarding the consensus document,8 I would add that specialists trained in endovascular treatment should also be trained to place ventricular drains and sensors for intracranial pressure monitoring, and to perform preventive decompressive hemicraniectomy after failed treatment with mechanical thrombectomy. In my opinion, hospitals accredited to perform endovascular treatment in certain types of strokes should have a physically present on-call specialist trained to perform the endovascular treatment of a ruptured aneurysm (having an expert in interventional neuroradiology stuck in a traffic jam is not very efficient). In the future, these activities may be performed by any specialist in neurosciences with the help of a robot.9 The tendency seems to be to have a specialist in cerebrovascular disease who from his/her workstation can analyse the Babinski sign and various scales, indices, and formulas (NIHSS, GCS, SPAN-100, RACE) that in addition to their applicability have been shown to be useful, and to assess the parameters provided by a multimodal CT scan, such as type of stroke, mean transit time, and collateral branches, all shown on a screen (telemedicine). The use of telemedicine is becoming more frequent in healthcare activity, with instructions given from the workstation or through a smartphone application that instructs the specialist trained to perform these manual operations, obviously with monitoring by an expert in cerebrovascular diseases (neurologist). The surgical microscope, a relic of the past century that is essential for the vascular neurosurgeon, will be replaced by telemedicine and robots9 controlled by intensive care specialists, anaesthetists, and other specialists from the multidisciplinary team, who are very interested in this type of disease. It is very healthy that in some centres, such as Hospital La Fe, neurologists are taking the lead in treating this type of stroke10 (as I have previously mentioned, in the past the disease was the responsibility of the neurosurgery department in many hospitals) and are demonstrating their ability as they have previously done with ischaemic strokes. This is a time of transition, in which vascular neurosurgeons, accustomed to operating with surgical microscopes, should become familiar with treating patients using screens and the copious information obtained through imaging studies. At this time, we should avoid outbursts of therapeutic enthusiasm and not operate/perform embolisation in certain patients (Fig. 2). The technique can be learnt in 3 months, but 3 years are needed to know when to administer it: the most difficult aspect is knowing when it should not be applied.

It find it surprising that Lago et al.1 do not mention why there were fewer cases of aSAH per year in the second period analysed (2007–2010), with approximately 23 per year, compared to 31 in the first period (1997–2005). The majority of authors report that this is the type of stroke with the most constant incidence.

There is a tendency to use the term vasospasm to refer to what should more properly be called delayed ischaemic neurological deficit; this is a kind of catch-all heading under which other systemic complications are sometimes included, such as metabolic alterations, infections, cardiac disorders, etc.2 These complications are frequent in frail patients, such as those with aSAH, and no significant difference is seen in their rates in the 2 periods analysed by Lago et al.1: 10.6% in the first and 9.2% in the second.

The 2 key factors, age and neurological status, determine the outcomes; I find it surprising that Lago et al.1 use the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Hunt and Hess score instead of the NIHSS, the most widely used tool in neurology. In my opinion, as neurologists are becoming more and more involved in leading the treatment of this type of stroke, establishing a consensus scale for all strokes would be very practical. In conclusion, in my humble opinion, it would be desirable to prepare guidelines with the participation of all interested parties to make a multidisciplinary approach for all strokes possible.

Please cite this article as: Vilalta J. Tendencias en el tratamiento de los aneurismas cerebrales: análisis de una serie hospitalaria. Neurología. 2020;35:128–130.