Many patients with cognitive symptoms, such as subjective memory complaints, may in fact have functional cognitive disorder.

DevelopmentThis review explores various aspects of functional cognitive disorder. We describe the clinical characteristics that support diagnosis. Diagnosis is not made by exclusion; rather, it is supported by positive findings, such as internal inconsistencies in cognitive symptoms. We also explore the mechanisms that could explain this condition, which include metacognitive errors, excessive self-monitoring, and abnormal emotional processing, among others. Functional cognitive disorders frequently copresent with other conditions, particularly with psychiatric disorders. We describe circumstances in which diagnostic support and neuropsychological assessment are required. Special emphasis is placed on the prognosis of this condition, which, despite the associated disability and distress, rarely progresses to dementia. Therefore, correct identification of cases and differentiation from mild cognitive impairment can help avoid unnecessary testing and reduce patient uncertainty. Treatment begins from the moment the patient is informed about their diagnosis, and is based on psychotherapy and metacognitive training.

ConclusionsPatients with functional cognitive disorder account for a significant percentage of consultations due to memory complaints and have particular needs. Use of specific clinical criteria allow early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Muchos pacientes con síntomas cognitivos, como aquellos con quejas subjetivas de memoria, pueden ser mejor clasificados en un trastorno cognitivo funcional.

DesarrolloA lo largo de esta revisión se exploran diversos aspectos del trastorno cognitivo funcional. Se describen las características clínicas que apoyan el diagnóstico, la necesidad de no considerarlo como un diagnóstico de exclusión, sino como una posibilidad que se sustenta en hallazgos positivos como la inconsistencia interna de los síntomas cognitivos. Se exponen los mecanismos que podrían explicar esta condición, los cuales incluyen las fallas en la metacognición, automonitoreo excesivo, procesamiento emocional, entre otras. Se explica la frecuente comorbilidad con otras condiciones, en particular con patologías psiquiátricas. Se describen circunstancias en donde se requieren apoyos diagnósticos y la valoración neuropsicológica. Se enfatiza en el pronóstico de esta condición, en donde, a pesar de llegar a ser incapacitante y acompañarse de angustia, muy pocos de los pacientes progresan a demencia, por lo que su correcta identificación permite diferenciarlos de aquellos con deterioro cognitivo leve, lo cual puede ayudar a evitar exámenes innecesarios y disminuye la incertidumbre para los pacientes. Finalmente, se explica como el tratamiento inicia desde el momento en que se comunica el diagnóstico al paciente, así como se puede apoyar en diversos enfoques de psicoterapia y reentrenamiento de la metacognición.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con trastorno cognitivo funcional dan cuenta de un porcentaje importante de las consultas por quejas de memoria y tienen necesidades particulares que pueden ser correctamente abordadas mediante criterios clínicos que permiten su identificación temprana y la selección de estrategias terapéuticas apropiadas.

Subjective memory complaints (SMC) constitute a frequent reason for consultation in clinical practice. Up to one-third of the general population may present cognitive symptoms at some point in their lives.1,2 As our understanding of dementia increases and new treatments for early stages of the disease are developed, more people are consulting due to SMC, which has led to an increase in the demand for memory clinics.3 Several conditions have been found to have a negative impact on cognitive function, including systemic diseases, psychiatric disorders, certain medications, and neurodegenerative diseases. Although the latter are the most concerning for patients, neurodegenerative disease is not diagnosed in the majority of cases of SMC, and progression to dementia is not observed.4 In many cases, no other cause for the symptoms can be identified; nonetheless, these complaints may still have a significant impact on patient function and represent a major source of concern and uncertainty.

Functional neurological disorders (FNDs) encompass a wide range of involuntary symptoms, which may be motor, sensory, cognitive, or convulsive, with typical manifestations that allow the identification of inconsistencies.5,6 Diagnosis of an FND is not made by exclusion, but rather is based on a set of diagnostic criteria that include certain signs and symptoms.7 Functional cognitive disorder (FCD), a type of FND, has previously been known by other names, including depressive pseudodementia, hysteria, dissociative state, psychological stress, brain fog, and disordered personality, which attests to the great heterogeneity of these disorders.2 As occurs with other FNDs, in the case of FCD, a targeted interview may help to reveal inconsistencies in patient-reported cognitive complaints,8 as well as to rule out the presence of an underlying psychiatric or medical condition that explains the symptoms.2

According to a systematic review, approximately 25% of patients attending specialist memory clinics with suspected dementia may actually have an FCD,2 either in isolation or as part of other FNDs or psychiatric comorbidities.9–11 Many of these patients have attended clinical consultations repeatedly and over long periods of time, undergoing unnecessary and costly tests, receiving inappropriate diagnoses or treatments, and suffering stigma and discrimination.12–14 Correct, early identification of the condition may enable better communication with patients and rational use of complementary tests, reducing the risk of misdiagnosis and contributing to the implementation of appropriate treatment strategies. This is the ultimate goal of this literature review.

Diagnostic criteriaThese criteria aim to correctly classify patients with SMC with a view to preventing misclassification into such categories as mild cognitive impairment (MCI),15–17 to enable early diagnosis based on positive findings, and to debunk the notion that FNDs may only be diagnosed by exclusion after an extensive aetiological study (Table 1).4,16

| 1. One or more symptoms of impaired cognitive function (frequently involving attention, concentration, or memory). |

| 2. Clinical evidence of internal inconsistencies between self-reported symptoms, conversational skills, daily functioning, and cognitive test results, as well as discrepancies in the level of concern displayed by the patient and their companions. |

| 3. Symptoms or deficit that are not better explained by another medical or psychiatric disorder; these may co-occur, but do not explain the magnitude and inconsistency of the symptoms. |

| 4. Symptoms or deficit that cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, or warrants medical evaluation. |

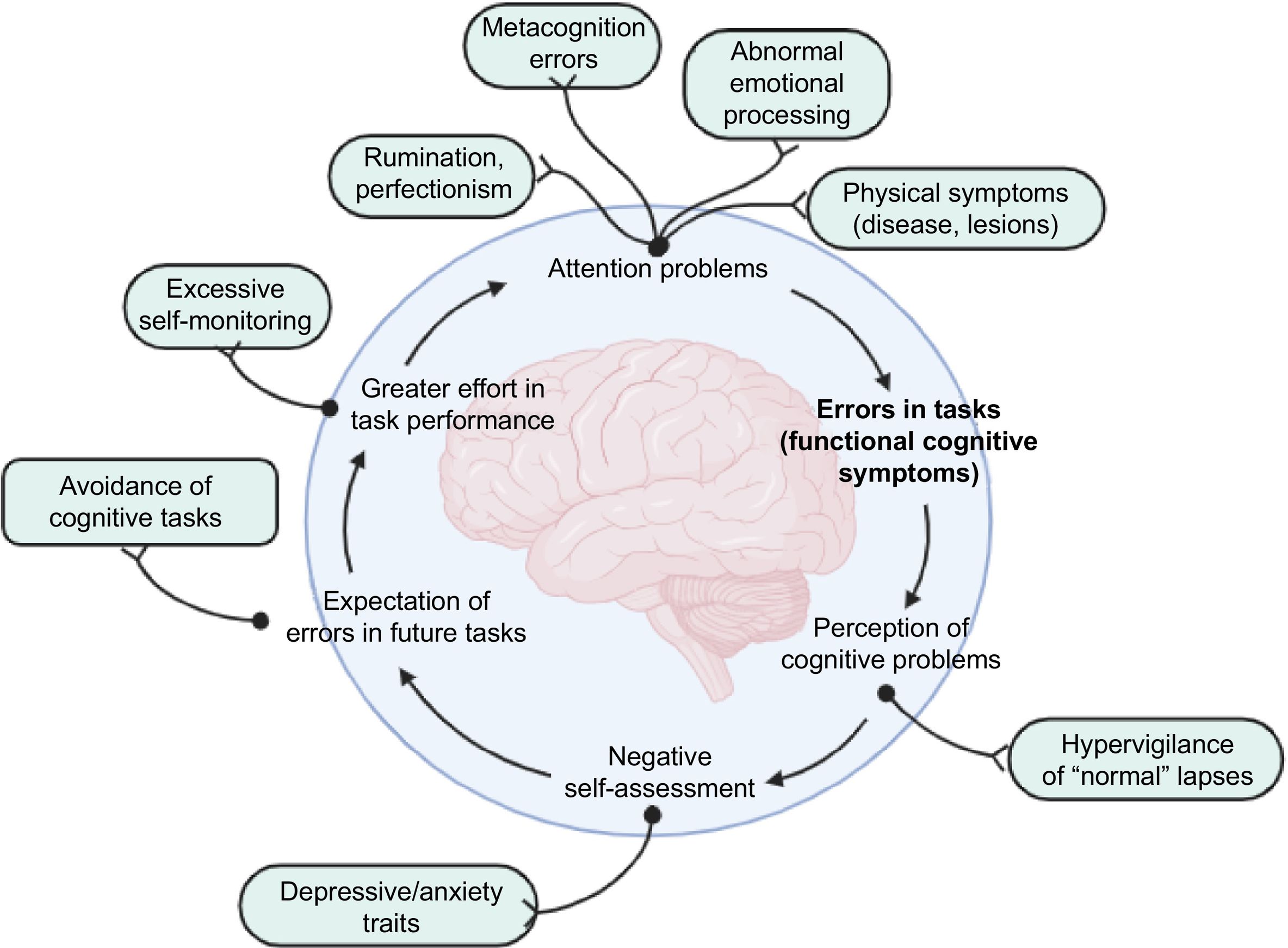

Several predisposing factors with a potential impact on the development of FCD have been described, including traumatic events, head trauma, brain lesions, and other physical causes or medical conditions. Mechanisms potentially predisposing to or favouring cognitive symptoms include global metacognition errors (i.e., errors in the way in which an individual assesses their own cognitive performance) and perfectionism in memory assessment, which ultimately results in low tolerance to memory lapses that may be considered normal in everyday life.18,19 The development of FCD has been associated with excessive self-monitoring, attentional bias, negative beliefs about the disease or ageing, health anxiety, perseverative cognition (rumination, obsession, worry), and abnormal emotional processing. These mechanisms may be reinforced by the concurrent presence of depressive or anxiety symptoms, and may be accompanied by more frequent cognitive problems and greater perceived effort in task performance, which creates a vicious cycle that results in over-attention on these cognitive symptoms (Fig. 1).11,20 Furthermore, family history of dementia is another determinant for consulting due to SMC, and is associated with greater health anxiety.21–23

Proposed pathogenic mechanisms of functional cognitive disorders. A wide range of behavioural, biological, and environmental factors, including perfectionism and increased self-monitoring of cognitive processes, may cause attention lapses and overinterpretation of these lapses in daily life, which may in turn trigger the prediction of future lapses, leading to a vicious cycle of inefficient cognitive function.

Internal inconsistency, a cardinal feature in the diagnosis of FCD, refers to an individual's ability to perform a task at certain times and inability to perform the same task at other times, particularly when it is the focus of attention. This suggests that the components involved in task execution are preserved, but that the individual presents difficulty fully engaging these components when they are required on demand; this points to differences between explicit and automatic processing.4

ComorbiditiesMCI and SMC share multiple features. In patients with MCI, neuropsychological tests detect impairment in some cognitive domains, whereas patients with SMC display more subjective symptoms. The existence of a pattern of linear progression has been proposed, according to which patients initially present SMC, subsequently progressing to MCI and ultimately to dementia. It should be noted, however, that not all cases of SMC invariably progress to dementia; rather, many patients may remain stable or even recover normal cognitive function. This is explained by the multiple causes of cognitive symptoms that may occur either in isolation or at the same time in a single patient, including medication, mild head trauma, post–COVID-19 symptoms, sleep disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, systemic or psychiatric disorders, and FCDs.4,11,16

Some patients with systemic, psychiatric, and/or neurological disorders may also present an FND. The same is true for FCD, which may be associated with psychiatric symptoms and even copresent with other neurological conditions4; however, further research is needed to determine whether they copresent with neurodegenerative disorders.

Many patients with dysthymia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, and depression may present cognitive symptoms, and particularly concentration problems and attentional difficulties. In these cases, when the severity of symptoms is considerable, physicians should aim to demonstrate the presence and degree of internal inconsistency of the cognitive symptoms in order to determine whether they are explained by an FCD rather than simply by the patient's psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, not all cases of cognitive symptoms due to inattention can be classified purely as FCD; rather, it should be analysed whether other comorbidities or FCD may be contributing to these symptoms.16 Conversely, not all patients with FCD meet criteria for psychiatric disorders24–26; therefore, this should not be regarded as an exclusion criterion.

Clinical assessmentAssessment of patients with SMC or other cognitive complaints may require longer consultation times, particularly due to the many somatic complaints and comorbidities reported by these patients.27,28 Therefore, it is important to establish a communication strategy enabling detection of positive signs,10 which, when analysed as a whole, help to differentiate FCD from other conditions, particularly neurodegenerative diseases (Table 2).

| Functional cognitive disorder | Neurodegenerative diseases |

|---|---|

| Patient attends alone. | Patient attends with a companion. |

| Great concern about their symptoms. | Companion is more concerned than the patient. |

| Patient answers questions independently. | Patient turns to companion for help. |

| Patient gives a detailed account of their symptoms. | Patient is unable to give a precise, detailed account of their symptoms. |

| Patient is able to answer complex questions. | Patient answers simple questions. |

| Deficits in recent memory and autobiographical memory. | Relatively preserved long-term autobiographical memory. |

| Frequent complaints of memory lapses for specific periods and events. | Unusual complaints of specific memory lapses. |

| The reported memory lapses may be considered normal. | The reported memory lapses are more serious than expected for the patient's age. |

| Patient gives approximate answers. | Patient does not give approximate answers. |

| Patient can give the exact date of symptom onset. | Patient is unable to accurately identify the date of symptom onset. |

| Unstable progression | Progressive course over time |

| Marked variability in symptomsa | Less marked variability in symptoms |

Clinical findings, language profile, and patient interaction patterns are helpful in the differential diagnosis between FCD and neurodegenerative diseases. Internal inconsistencies in the patient's symptoms can be demonstrated in different ways.4 Patient-reported cognitive complaints can be compared against the cognitive skills displayed by the patient during the interview. In fact, many of these patients go to a memory clinic of their own accord30 and display higher levels of self-confidence and independence in daily activities; furthermore, the importance they assign to their memory complaints stands in contrast with that attributed by their relatives or close friends.2,9 During the interview, they experience less difficulty communicating; provide longer answers; are able to answer complex questions about their memory complaints; repeat previous content; give accurate, detailed information on symptom onset; and are able to provide detailed and accurate accounts of the situations, tasks, or contexts (typically of high cognitive demand) where cognitive problems appear.4 Despite all the difficulties reported by these patients, they do not usually need help from their companions to answer questions. Patients with neurodegenerative diseases, in contrast, usually give specific or short answers, appear insecure, do not provide additional details or examples, are unable to report the exact date of symptom onset, and rarely provide a specific context for their symptoms (Table 2).9,10,31

The complaints of patients with FCD rarely involve cognitive domains other than memory. Many of them report amnestic blocks for previously learnt information, such as names, familiar places, and birthdays: they have difficulty retrieving this information on demand but are later able to recall it with a certain degree of effort, which is perceived as exaggerated. Interestingly, patients are able to recall these amnestic episodes and the perceived exaggerated effort in great detail.32

Regarding demographic factors, patients with FCD are usually younger than those with neurodegenerative diseases, although FCD may also occur in people over the age of 60; therefore, old age should not be considered an exclusion criterion for FCD.27 Most patients in the middle-age range consult or are referred to memory clinics due to their significant concern about developing a neurodegenerative condition at older ages.4 Other demographic factors that should be considered are education level and family history. Many patients with FCD have high education levels and cognitively challenging jobs.24,27

Differential diagnosisIn clinical practice, attentional symptoms are observed in nearly all cases of FNDs.15 For example, many patients with motor FNDs or non-epileptic paroxysmal events present cognitive symptoms that may be encompassed within the spectrum of FCD, suggesting common pathogenic mechanisms.33,34

Diagnosis of FCD should be made with caution, particularly in elderly patients or young patients with family history of neuropsychiatric disease and attention problems, who may actually have a neurodegenerative disorder manifesting with psychiatric prodromal symptoms.15,35 Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder may be misdiagnosed as FCD; therefore, physicians should review these patients' histories to detect symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity and evaluate school performance before the age of 12&#¿;years.36,37 History of head trauma is not uncommon. The type of trauma and its complications should be assessed with a view to establishing an association with symptoms and the presence of post-concussion syndrome, which may co-occur with FCD.4

Simulation or malingering is the feigning or exaggeration of symptoms of a disease, including cognitive symptoms.38 Slick et al.39 proposed a set of diagnostic criteria for malingered neurocognitive dysfunction, which include presence of an external incentive for feigning or exaggerating symptoms during the examination; clinical presentation that is inconsistent with the expected course of the disease; inconsistencies during assessment; psychometric evidence from performance validity tests (PVTs) and symptom validity tests; and marked discrepancies between test data, self-reported symptoms, the expected course of the condition, and reliable collateral reports.38–40

Table 3 summarises the main factors to be considered in differential diagnosis, with particular focus on other conditions that may present internal inconsistencies.

| Finding | Description | Relevant aetiologies |

|---|---|---|

| Internal inconsistencies in language | Difficulty understanding isolated words rather than phrases or sentences | Aphasia/semantic dementia |

| Visuospatial internal inconsistency | More marked difficulty perceiving objects or movement | Posterior cortical atrophy |

| Executive internal inconsistency | More marked involvement during daily activities than during tests conducted at the consultation | Dorsolateral frontal involvement |

| Amnestic internal inconsistency | Declarative memory deficits with no alterations in implicit memoryMore marked deficits in recognition than in recall | Wernicke–Korsakoff syndromePerirhinal or parahippocampal damage |

| Apathy | Less motivated to provide spontaneous responses as compared to requested responses | Different causes, with frontal lobe involvement |

| Symptom variability | Changes in symptom intensity in daily life | Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, Lewy body dementia, delirium |

| Predominantly non-amnestic profile | Particularly in individuals younger than 60&#¿;years | Early-onset AD |

| Sudden onset | Acute-onset, persistent symptoms | Vascular aetiology |

| Lack of progression over time | Good functional status, education level, and lifestyle before the disorder | High cognitive reserve in neurodegenerative diseases |

| Memory lapses | Self-limiting anterograde and retrograde amnesia | Transient global amnesia |

| Systemic symptoms | Copresence of fatigue, daytime sleepiness, weight loss, or other alterations | Consider other medical causes |

AD: Alzheimer disease.

Patients with FCD are not usually relieved by negative test results, but rather show increased concern. The use of diagnostic criteria for FCD may help to achieve early diagnosis and ensure a more rational use of complementary tests. However, depending on the opinion of the treating physician, some cases may require additional tests, especially those included in cognitive assessments.41–43 Structural imaging studies may be useful for ruling out other diseases and may provide data on neurodegenerative causes. We should also be mindful of the possibility of incidental findings on magnetic resonance imaging, which may exacerbate patients' anxiety. Furthermore, we must also be aware that these patients may present age-related changes, and even mild-to-moderate global brain atrophy, with no impact on cognitive performance.2,43,44

In young patients with unexplained cognitive impairment, long-term progression, or atypical presentations, such functional studies as FDG-PET, SPECT, or amyloid PET imaging may be considered. However, it should be noted that a considerable percentage of patients displaying positive PiB-PET results and MCI will not develop dementia.45 Unlike in other FNDs,46 published data from brain functional MRI studies in patients with FCD are still insufficient.

Neuropsychological assessmentCognitive test results must be interpreted in combination with the findings of the clinical assessment. Cognitive screening tests play an essential role in the diagnosis of dementia, but still present limitations for categorising groups according to normative ranges. Therefore, if they are used as “dementia tests,” the number of false positives will increase, even among individuals with FCD.16

Some patients with FCD may perform above the expected levels, although in general terms these patients' cognitive performance is similar to that of healthy controls.21 Patients with SMC have shown similar or poorer performance to that of healthy controls, but better than patients with MCI or dementia.2 No consistent data are available on the cognitive profile of patients with FCD and the differences with other neurodegenerative diseases. However, some studies do demonstrate the importance of assessing such cognitive domains as memory, attention, information processing speed, and executive function with sufficiently sensitive tests to detect potential deficits. Likewise, considering the high comorbidity burden of FNDs, assessment should include screening tests for detecting such psychological and neuropsychiatric symptoms as anxiety and depression, or certain personality traits, with a view to evaluating the effect of these symptoms on cognitive performance.47,48

The cognitive domains most frequently showing poor performance in neuropsychological tests are those related to attention, concentration, and executive function.25 Objective signs of cognitive involvement on tests assessing language, visuospatial skills, praxias, or visual agnosia constitute a warning sign.7 Less frequently, patients display short-term memory alterations compared to patients with suspected neurodegenerative disease, and inconsistencies in divided and selective attention tasks.11,26 When assessing these results, we must bear in mind that many patients with FCD, at the time of cognitive assessment, may show high levels of stress due to the assessment (alterations in self-monitoring and high expectations), which may in turn interfere with test performance.2,11,26,27,44 Some patients show difficulty completing simple tests, such as orientation in time or following directions, which stands in contrast with their performance in daily life. Furthermore, they usually perform better on more difficult tests, give approximate answers, worry about potential mistakes, or are pessimistic about their performance. These behaviours are not commonly observed in patients with neurodegenerative disorders, which supports the idea that patients with FCD exhibit cognitive deficits that are context-dependent.4,21,26,49 In this context, the inclusion of incidental learning tests, such as the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test, may reduce biases by preventing the patient from feeling that they are being explicitly evaluated.

In some cases, patients with FCD perform significantly better than those with MCI in the delayed free recall and retention tasks of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, one of the most widely used tools for the assessment of verbal learning and memory. However, those with FCD display spared delayed recall and retention, in comparison to impaired immediate recall and recognition. This pattern, which differs from that observed in prodromal neurodegeneration, is also a marker of internal inconsistency.26

In patients with malingering or simulation, neuropsychological tests reveal inconsistencies. Exaggeration can be observed in memory recognition, atypical error patterns in problem-solving tasks, greater impairment in gross motor tasks than in fine motor tasks, abnormal performance in digit span tests, and atypical patterns in language and attention tests.39 In this context, PVTs may be useful as they aim to measure effort or detect bias toward negative responses. The results of these tests can be particularly helpful if performance is very poor and if several types of PVTs are combined.39 It should be noted that PVTs are sometimes conducted as part of routine cognitive assessment, with a view to detecting inadequate, exaggerated, or feigned efforts. However, failures have been reported when PVTs are applied to patients with FCD or neurodegenerative conditions; the results should therefore be interpreted with caution.50

PrognosisFCD does not progress significantly over time, although it may persist or fluctuate. Some patients may regress to their previous cognitive status, stabilise, or, in very rare cases, progress very slowly over time.4 For this reason, diagnosis can be established early, with long-term follow-up reserved only for uncertain cases, particularly in older populations.16

With appropriate clinical assessment, the likelihood of misdiagnosis is low. In a cohort of 46 patients diagnosed with FCD at a memory clinic and followed up for 20&#¿;months, 13% presented symptom resolution, and only one was diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease.50,51 These results also call attention to the high percentage of patients with persistent symptoms and possibly with an impact on functional status, which further supports the notion that FCD is not “benign.”

It is possible that many patients misdiagnosed with MCI, who do not show clinical deterioration in the long term or who recover normal cognitive function, are in fact cases of FCD.40–53 Further research will help to determine whether FCD may constitute the prodrome of some types of dementia, as is the case with motor FNDs in the prodromal stage of Parkinson's disease.54

TreatmentTreatment starts when the patient is informed of their diagnosis, which helps to alleviate the uncertainty they feel after repeated consultations. As has been implemented in other FND, sufficient time should be dedicated during consultations to explain the positive findings that support the diagnosis, as well as the inconsistencies that reinforce it.55 Furthermore, physicians should inform patients that memory lapses, distractions, and other attention problems are common in cognitively healthy individuals,1,55 and provide them with a general overview of metacognition, the importance of attention for memory performance, and the role that work, social factors, expectations, perceptions, and the demands of daily living may play in their symptoms.

No specific medications are currently available for FCD. Although many of these patients have comorbidities (mainly psychiatric) that must be treated and followed up to determine their role in cognitive symptoms, there is no consensus to date on whether specific pharmacological treatment for functional cognitive symptoms should be started. Normal human experiences should not be medicalised: pharmacological management should only be considered for the treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.16

Other medical approaches include observation, assuaging patients' concerns, psychological assessment, identifying the use of medications with harmful psychoactive effects, and community mental health approaches.16 Unfortunately, many of these patients are discharged, while we believe that they should be followed up by the neurologists, psychiatrists, or neuropsychiatrists that issued the diagnosis to ensure that they are accompanied, monitored, and periodically assessed.

Different psychotherapeutic approaches have been proposed for the treatment of FCD, including metacognitive training, acceptance and commitment therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy.20 These approaches provide patients with the tools needed to cope with rigid thinking and excessive worry about memory lapses, and promote behaviours that optimise attention. A randomised clinical trial including 40 patients with attention problems and memory dysfunction evaluated an intervention consisting of psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, stress management, relaxation, and mindfulness techniques. Patients in the experimental group showed significant improvements in self-perceived memory performance at 6&#¿;months.56 Another clinical trial including patients with SMC reported similar results after an intervention consisting of 10 sessions of metamemory training.56,57

As in other FNDs, cognitive rehabilitation may be useful for the treatment of FCD due to the involvement of attention to symptoms in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of the disorder; comorbid motor and psychological symptoms may also benefit from this approach.47,48 At present, metacognition is being studied and applied using computer-based training strategies, which may provide new opportunities for patients with FCD.56–59 However, further research on interventions for patients with SMC is needed.60 Recent studies have addressed the differences between local and global metacognition, and how these differences may help us to better understand these patients' symptoms.61

ConclusionsPatients with FCD account for a significant percentage of all consultations due to memory complaints. These patients frequently present comorbidities. FCD may be identified through a targeted interview aimed at detecting internal inconsistencies in the reported symptoms. Patients with FCD have specific needs, which may be addressed using clinical criteria enabling early identification and selection of appropriate therapeutic strategies. FCD frequently stabilises or even improves over time, although some cases may progress to dementia. Further research is needed to determine the pathogenic mechanisms of FCD and its comorbid or prodromal presentation with other neurodegenerative diseases. Future clinical studies with long-term follow-up should be conducted to better define the prognosis of FCD and evaluate these patients' response to different treatment approaches.

FundingNone.

Patient informed consentNot applicable.

Ethical considerationsThis type of study does not require approval by an ethics committee.