Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic multifocal inflammatory demyelinating disease that progresses with neurodegeneration and is associated with a high risk of disability.

ObjectivesWe describe a series of patients diagnosed with MS in the past 10 years at a secondary hospital in Colombia.

MethodsWe conducted a descriptive, retrospective study of a series of patients attended at the outpatient clinic of the neurology department of Hospital Regional de la Orinoquía, in Colombia, between 2013 and 2022, and who were diagnosed with MS according to the McDonald criteria.

ResultsWe included 15 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MS; 66.7% were women, with a mean age of 42 years (range, 16–71). Mean time from symptom onset to inclusion in the study was 87.4 months; 20% of patients presented disability. The distribution by type of MS was as follows: 20% patients had primary progressive MS, 20% had secondary progressive MS, 40% had clinically isolated syndrome, and 20% had relapsing–remitting MS. The mortality rate was 20%, with a median survival time of 89.83 months.

ConclusionsAlthough treatment achieves significant improvements in symptoms and quality of life at every stage of the disease, early diagnosis is essential to prevent progression to disability.

La Esclerosis Múltiple (EM) es una enfermedad inflamatoria desmielinizante crónica multifocal que evoluciona con neurodegeneración y alto riesgo de discapacidad.

ObjetivoSe busca caracterizar a la población diagnosticada con EM en los últimos 10 años en un hospital de segundo nivel colombiano.

MétodosSe realizó una serie retrospectiva y descriptiva de casos de pacientes atendidos en un hospital entre el año 2013-2022 a quienes se les confirmo el diagnóstico de esclerosis múltiple según los criterios de Mc Donald (4,12), realizado por el servicio de neurología en la consulta ambulatoria del Hospital Regional de la Orinoquía.

ResultadosSe selecciono una serie de 15 registros de pacientes con diagnostico confirmado de EM, el 66,70% de los pacientes eran de sexo femenino, con un promedio de edad de 42 años, rango entre los 16 años y los 71 años. La media del tiempo de inicio de los síntomas en meses con respecto al año del estudio fue de 87.4 meses, el 20% progreso a discapacidad, Según el diagnostico por tipo de EM el 20% correspondió a EMPP, 20% a EMSP, 40% a SCA y el 20% EMRR. La mortalidad reportada en este estudio fue del 20%, y la mediana de supervivencia fue 89.83 meses.

ConclusionesA pesar de que los tratamientos aportan una sustancial mejora en los síntomas en cada etapa de la enfermedad y calidad de vida a los pacientes que la padecen, debe ir de la mano de un diagnóstico temprano y oportuno, buscando prevenir la progresión a discapacidad.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic multifocal inflammatory demyelinating disease that progresses with neurodegeneration. It is caused by an abnormal autoimmune response in genetically predisposed individuals, with several environmental factors affecting disease progression. Over 2.8 million people worldwide have MS, and 1 in every 3000 people lives with MS.1–3 A latitude gradient for the disease has been described in Latin America: incidence is higher in southern countries and in northern Mexico, and considerably lower in populations nearer the equator; in Colombia, the prevalence of MS is 1.48–4.98 cases per 100 000 population.4

Diagnosis of MS is clinical, based on the identification of neurological signs and symptoms and their correlation with compatible white matter lesions.5 Cerebrospinal fluid analysis must be performed to rule out other conditions and to demonstrate intrathecal oligoclonal immunoglobulin synthesis, which is indicative of an abnormal CNS autoimmune response.6 Oligoclonal bands (OCB) and the IgG index are used for intrathecal IgG detection. As OCB are present in over 90% of patients with MS, this technique is currently the gold-standard for biochemical diagnosis of MS, despite its high cost. Furthermore, presence of OCB constitutes an independent risk factor for progression to MS in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS).7,8

CSF and serum kappa-free light chain determination has gained popularity in recent years, showing similar sensitivity and specificity to OCB. An added benefit of this marker is that it is an automatic, fast, and reliable process.6,9–11 Given its progressive course and associated risk of disability, early detection of MS is essential; this will enable appropriate symptom management.12 The aim of this study is to describe the population diagnosed with MS in the past 10 years at a secondary hospital in Colombia.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationWe describe a retrospective series of patients diagnosed with MS at our hospital over the last 10 years.

Selection criteriaInclusion criteria: Patients attended at the outpatient service of the neurology department of Hospital Regional de la Orinoquía between 2013 and 2022, and diagnosed with MS according to the McDonald criteria.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with suspected MS in whom MS was ruled out.

Data collection processWe reviewed the clinical records of patients with a diagnosis of MS, using the DGH software and filtering by ICD-10 code G35X. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we gathered a total of 15 patients.

VariablesWe recorded sociodemographic (age, sex, and origin) and clinical variables (history of infection, allergies, obesity, initial manifestations, diagnostic test results, behaviour, and outcome). EDSS scores were confirmed by a neurologist from the research team.

Statistical analysisWe built an ad hoc tool to collect data on the study variables from the clinical records; data were subsequently analysed using Microsoft Excel 2013. The univariate analysis included descriptive statistics; data were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages). Quantitative data were expressed as measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD], quartiles 1 and 3 [Q1–Q3]), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Risk of biasMany patients were admitted due to strong suspicion of multiple sclerosis but were subsequently transferred to other centres; therefore, we were unable to access their clinical records and their final diagnosis is unknown. Some patients were lost to follow-up. The most recent time of data collection was February 2023. The data from patients lost to follow-up were considered censored data, and were included and analysed up to the point at which these patients dropped out of the study.

Ethical considerationsOur study was approved by our hospital's clinical research ethics committee (report no. 004, dated 25 January 2023).

ResultsPatient sampleWe obtained data from 1150 clinical records of patients diagnosed with MS (ICD-10 code G35X) (Fig. 1).

Sociodemographic characteristicsWomen accounted for 66.70% of the sample, whereas 33.30% were men. Mean age was 42 years (SD: 17.39; 95% CI, 33.19–50.80), with a range of 16–71 years (Q1–Q3: 27–54); the age distribution of the sample is shown in Fig. 2. All patients lived in urban areas; 81.25% of the sample had a low socioeconomic level and 18.75% had a medium socioeconomic level.

With respect to the population group, 100% belonged to “other population groups,” with no patient belonging to a vulnerable population group. Regarding ethnicity, 93.34% identified as “other” (non-minority ethnic), and one patient identified as indigenous (6.66%). No patient identified as Raizal, black, or Afro-Colombian.

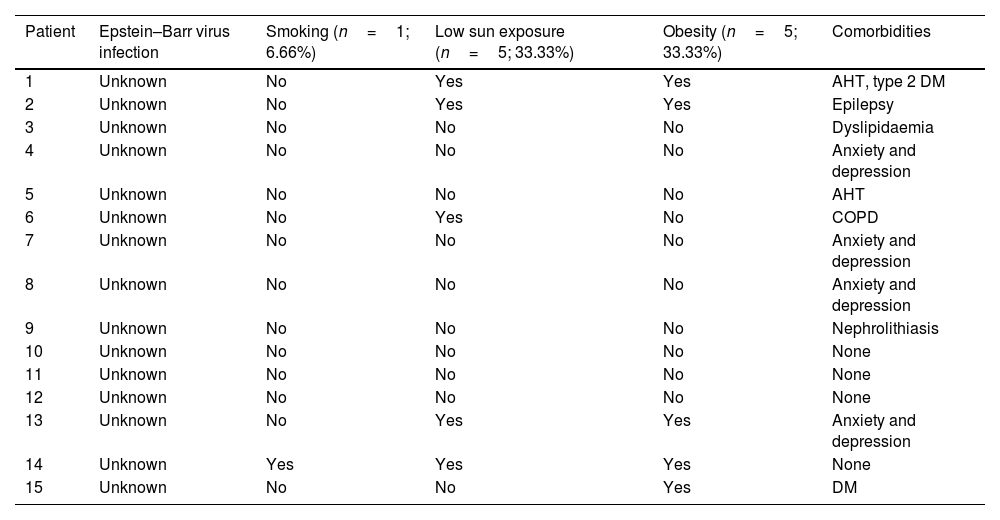

Clinical characteristicsSome patients presented risk factors associated with predisposition to MS, such as history of infectious mononucleosis, smoking, low sun exposure, and obesity (Table 1).

Risk factors for MS in the series.

| Patient | Epstein–Barr virus infection | Smoking (n=1; 6.66%) | Low sun exposure (n=5; 33.33%) | Obesity (n=5; 33.33%) | Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown | No | Yes | Yes | AHT, type 2 DM |

| 2 | Unknown | No | Yes | Yes | Epilepsy |

| 3 | Unknown | No | No | No | Dyslipidaemia |

| 4 | Unknown | No | No | No | Anxiety and depression |

| 5 | Unknown | No | No | No | AHT |

| 6 | Unknown | No | Yes | No | COPD |

| 7 | Unknown | No | No | No | Anxiety and depression |

| 8 | Unknown | No | No | No | Anxiety and depression |

| 9 | Unknown | No | No | No | Nephrolithiasis |

| 10 | Unknown | No | No | No | None |

| 11 | Unknown | No | No | No | None |

| 12 | Unknown | No | No | No | None |

| 13 | Unknown | No | Yes | Yes | Anxiety and depression |

| 14 | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | None |

| 15 | Unknown | No | No | Yes | DM |

AHT: arterial hypertension; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM: diabetes mellitus.

Source: clinical records (DGH software).

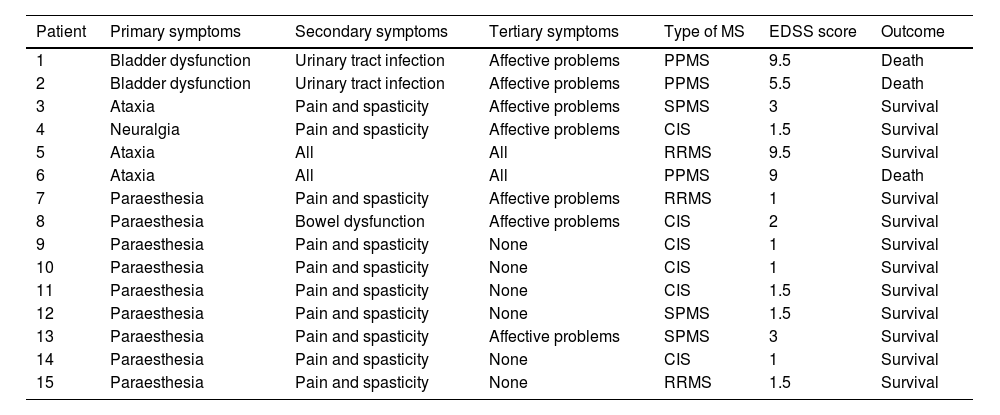

Table 2 presents the clinical characteristics of our sample. Primary symptoms include ataxia, paraesthesia, fatigue, cognitive deficits, bladder and bowel dysfunction, dysaesthesia, and neuralgia. Secondary symptoms include spasticity-related pain and urinary tract infections secondary to bladder dysfunction. Tertiary symptoms include psychological alterations secondary to stress (work-related, personal, or affective problems) associated with chronic disease. Mean (SD) time from symptom onset to inclusion in the study was 87.4 (53.41) months (95% CI, 60.37–114.43).

Clinical characteristics of the series.

| Patient | Primary symptoms | Secondary symptoms | Tertiary symptoms | Type of MS | EDSS score | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bladder dysfunction | Urinary tract infection | Affective problems | PPMS | 9.5 | Death |

| 2 | Bladder dysfunction | Urinary tract infection | Affective problems | PPMS | 5.5 | Death |

| 3 | Ataxia | Pain and spasticity | Affective problems | SPMS | 3 | Survival |

| 4 | Neuralgia | Pain and spasticity | Affective problems | CIS | 1.5 | Survival |

| 5 | Ataxia | All | All | RRMS | 9.5 | Survival |

| 6 | Ataxia | All | All | PPMS | 9 | Death |

| 7 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | Affective problems | RRMS | 1 | Survival |

| 8 | Paraesthesia | Bowel dysfunction | Affective problems | CIS | 2 | Survival |

| 9 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | CIS | 1 | Survival |

| 10 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | CIS | 1 | Survival |

| 11 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | CIS | 1.5 | Survival |

| 12 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | SPMS | 1.5 | Survival |

| 13 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | Affective problems | SPMS | 3 | Survival |

| 14 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | CIS | 1 | Survival |

| 15 | Paraesthesia | Pain and spasticity | None | RRMS | 1.5 | Survival |

CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS: relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis.

Source: clinical records (DGH software).

According to the records, all patients with behavioural alterations were referred to a higher-level hospital. Three patients (20%) progressed with disability, with a mean EDSS score of 3.43 (SD: 3.27; 95% CI, 1.77–5.08). Distribution by type of MS was as follows: 20% patients had primary progressive MS (PPMS), 20% had secondary progressive MS (SPMS), 40% had CIS, and 20% had relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS).

The mortality rate in our series was 20%; 1 patient died within 5 years of diagnosis and the remaining 2 died after more than 10 years of disease progression. Median survival time was 89.83 months (SD: 62.54; 95% CI, 55.92–123.74).

DiscussionThe literature includes a qualitative, descriptive study conducted in Granada,13 following a phenomenological and interpretative approach, which included 30 participants with MS aged 28–66 years, of whom 19 were women (63.33%) and 11 men (36.66%). This sex distribution is similar to that of our study.

In another study, conducted in Peru,14 the authors reviewed the clinical records of 98 patients with a diagnosis of MS who were admitted to the neurology department of Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen between 2001 and 2015. By MS type, mean age was 34.3 years in the RRMS group, 40.7 years in the SPMS group, and 40.6 years among patients with PPMS. Women accounted for 51.7% of the sample. Most patients were from Lima (61.5%), while 37.4% came from other regions in Peru and 1.1% were from other countries. Regarding risk factors for MS, 29 patients (31.9%) were smokers. No other relevant medical history was observed. This study presents similarities with our own in terms of sex distribution, urban origin of the patients, history of smoking, and median age.

The most frequent comorbidities in patients with MS are depression (23.7%) and anxiety (21.9%), followed by arterial hypertension (18.6%), dyslipidaemia (10.9%), and chronic pulmonary disease (10%)15,16; these comorbidities were also found in our series.

In a study into the factors associated with time of disability progression in patients with MS attended at a centre specialising in MS in Medellín, Colombia, between 2013 and 2021, Arteaga-Noriega et al.17 included 219 patients, 25% of whom progressed to disability, with a median survival time of 78 months (Q1–Q3: 70–83). Our study, also conducted in Colombia, obtained similar results.

Among the consensus recommendations on the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with SPMS,18 the most prevalent type of MS in this study, experts recommend follow-up assessments every 3 months and an MRI study annually.19 Clinical evaluation should be performed at specialised centres by trained personnel. Similarly, the diagnosis and treatment of adults with MS according to clinical practice guidelines20 should employ specific algorithms designed for this population.

ConclusionsMS presents with a broad range of symptoms and its management includes specific palliative treatments. As we currently lack a cure for the disease, these treatments have contributed to a substantial improvement in symptoms at each stage of progression, improving these patients' quality of life. However, timely diagnosis is essential to prevent progression to disability.

FundingNo funding was received for this project.

Informed consentDue to the descriptive, observational nature of the study, in which no intervention was performed, written informed consent was not required. The study was approved by the local healthcare research ethics committee.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by our hospital's healthcare research ethics committee (report no. 004, dated 25 January 2023).

Author contributionsStudy planning and performance: LGA, KAMB, JSPB, JCVC, CEOM; study design and data collection: LGA, JSPB, KAMB; analysis and presentation of results: LGA, JSPB, KAMB; drafting of the manuscript: LGA, JCVC, JSPB; final review and approval of the manuscript: KAMB, LGA, JSPB, JCVC, CEOM.