Sexual dysfunction (SD) is a commonly overlooked issue following ischemic stroke (IS), influenced by various risk factors including social, psychological, and biological factors. This study aims to investigate the prevalence and risk factors associated with SD in adult male patients who have experienced an IS.

MethodsA descriptive observational cross-sectional study was conducted in Bogotá, Colombia, involving adult male IS patients. Sociodemographic, medical history, pharmacological history, substances consumption, and time since stroke data were collected. Clinical assessments were performed using the NIHSS score, modified Rankin score (mRankin), pain score, and mood evaluation (Beck inventories). The Arizona Sexual Experience (ASEX) scale and the frequency of sexual encounters were used to assess SD.

Results50 males included, mean age 63.2 (±9.7) years. The most prevalent medical comorbidities were arterial hypertension (84%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) (46%). Anxiety or depression were identified in 48%. The mean scores for the NIHSS, mRankin, and pain were 6, 1, and 1, respectively. The average time from IS to clinical assessment was 6.5 months. Sexual dysfunction was observed in 18 (36%) subjects. Age (OR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.247) and location of the IS in the cortico-subcortical region of the parietal, temporal, or occipital lobes (OR 13.59, 95% CI: 1.58–405.784) were associated with SD.

ConclusionSD affects more than one-third of male patients with IS, age, and IS location identified as key risk factors. Comprehensive assessment of sexual function should be incorporated into this patients.

La disfunción sexual (DS) después de un infarto cerebral (IC), es un problema subvalorado, influenciado por diversos factores de riesgo, incluyendo aspectos sociales, psicológicos y biológicos. Este estudio busca investigar la prevalencia y los factores de riesgo asociados con la DS en hombres que han experimentado un IC.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo observacional de corte transversal en Bogotá, Colombia, con pacientes adultos de sexo masculino con IC. Se recopilaron datos sociodemográficos, antecedentes médicos, historial farmacológico, consumo de sustancias y tiempo transcurrido desde el IC Se realizaron evaluaciones clínicas utilizando la Escala NIHSS, la escala modificada de Rankin (mRankin), la puntuación de dolor y una evaluación del estado de ánimo (inventarios de Beck). Se utilizó la Escala de Experiencia Sexual de Arizona (ASEX) y la frecuencia de encuentros sexuales para evaluar la DS.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 50 hombres, con edad media de 63.2 (+/−9.7) años. Las comorbilidades médicas más prevalentes fueron hipertensión arterial (84%) y diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (46%). Se identificaron síntomas de ansiedad o depresión en el 48% de los pacientes. Las puntuaciones medias para NIHSS, mRankin y dolor fueron de 6, 1 y 1, respectivamente. El tiempo promedio desde el IC hasta la evaluación clínica fue de 6.5 meses. Se observó DS en 18 (36%) sujetos. La edad (OR 1.12, IC 95%: 1.02–1.247) y la ubicación del IC en la región cortico-subcortical de los lóbulos parietal, temporal u occipital (OR 13.59, IC 95%: 1.58–405.784) se asociaron con DS.

ConclusiónLa DS afecta a más de un tercio de los pacientes masculinos con IC y la edad y la ubicación del IC fueron identificadas como factores de riesgo clave. Se sugiere incorporar una evaluación integral de la función sexual en estos pacientes.

Ischemic stroke (IS) is the leading cause of disability in adults.1 The effects of IS are multiple and varied, impacting work, family, and personal domains and with deleterious consequences in sexual function. Sexual dysfunction (SD) is common in patients with IS, affecting both genders and all age groups.2,3

Berner et al. reported erectile dysfunction in 48% of 605 adult male subjects with a history of IS.4 Pistoia et al. described decreased libido in 26%–79%, decreased frequency of coitus in 33%–64%, and erectile dysfunction in 20%–74% of IS patients.5

SD in IS patients is multifactorial and related to biological, psychological, and social factors. Contributing causes of SD in IS patients can be broadly classify as primary, secondary, and tertiary.6 Primary causes are derived from the central nervous system injury,5,7 from comorbidities (such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, and heart disease), and prescribed medications.6,7 Secondary causes originate from IS sequelae, including motor, sensory, visuospatial, and sphincter disorders, among others.6 Hemihypoesthesia and hemineglect following IS can interfere with erotic sensation.8 Tertiary causes involve psychological, affective-emotional, and cognitive-behavioral consequences, such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, role reversal, and fear of recurrence.6,8,9 Furthermore, several studies have shown a significant decrease in libido, frequency of intercourse, sexual arousal, and sexual satisfaction in partners of IS patients.7,10

SD is a common problem not only in IS patients but also in individuals with a wide range of neurological diseases. However, SD in neurological patients it is often underdiagnosed and underappreciated. A survey conducted in Colombia revealed that only 64% of neurologists regularly assess sexual function in patients with neurological disorders. Reasons for this include lack of knowledge about the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of SD in neurological patients, including those with IS.11

The aim of this investigation was to study SD in Colombian male adult patients with a history of IS. We consider that understanding the epidemiology, characteristics, and variables associated with SD in IS patients is the initial step towards providing treatments that improve sexual function and the quality of life for those affected by it.

Materials and methodsA descriptive observational cross-sectional study was conducted at the Fundación Cardio-infantil in Bogotá, Colombia. Adult male patients between the ages of 18 and 80 years who provided informed consent and had a confirmed history of IS assessed by clinical and neuroimaging criteria (computed tomography and/or brain magnetic resonance imaging) were recruited from the neurology outpatient clinic. Subjects with SD before the IS, ongoing SD treatments, neurological diseases with autonomic compromise (such as spinal cord injury or peripheral neuropathy), medical treatments affecting testosterone levels or function, neuropsychiatric diseases or conditions that would preclude their participation as determined by the investigator, extensive penile or pelvic surgery (excluding non-radical prostatectomy), radiation therapy to the abdomino-pelvic region, aphasia, dementia or cognitive impairment (determined by history or Mini-Mental State Examination score <25), and transient ischemic attack were excluded.

In a single clinical visit sociodemographic, medical history, alcohol/cigarette consumption, pharmacological history, and time since IS data were collected. Clinical assessments performed in the visit included physical and neurological examinations, the MMSE test, NIHSS (National Institute of Health Stroke Scale, ranging from 0 to 42 with higher scores indicating greater neurological deficit), modified Rankin scale (ranging from 0 to 5 with higher scores indicating greater disability), pain average in the last month or since the IS through the visual analog scale (VAS), and mood with the Beck depression and anxiety inventory (ranging from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression or anxiety). Sexual function was assessed with an open question on the frequency of sexual activity per month since the IS and the Arizona Sexual Experience scale (ASEX), a self-applied scale previously validated in Spanish and Colombian population.12 The ASEX scale consists of 5 questions with multiple-choice answers concerning sexual desire, sexual interest, erections in men, and orgasms. Sexual dysfunction is present if the total score is greater than 19, or the score for any item is greater than 5, or if the score for 2 or more items is greater than 4. Additionally, the most recent neuroimaging was evaluated with description of the number and anatomical location of the infarcts and for the presence of white matter lesions according to the Fazekas classification. For the description of anatomical location of each IS, the following classification was used: A first category of the involved structure (lobar, basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, and brainstem) and a second category based on the laterality of the lesion (right and left). For lobar lesions, 2 subcategories were used: For each lobe (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital) and based on depth of the lesion in predominantly cortical–subcortical and predominantly subcortical. For lesions that were not readily classifiable the authors reach a consensus and assigned a category.

Based on the frequency of decreased libido described by Choi-Kwon et al. (44%),13 an alpha of 0.05, and an absolute error of up to 10%, a sample size of 95 subjects was calculated. Qualitative variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies, continuous variables are presented as measures of central tendency and dispersion according to their distribution and the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. An exploratory bivariate analysis was conducted to compare the distribution of baseline and clinical characteristics between subjects with and without SD according to the ASEX scale score. For qualitative variables, Chi-Square or Fisher's exact tests were used depending on expected values, while t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests were performed for quantitative variables based on the distribution of the variables. p-values less than or equal to .05 were considered statistically significant. Finally, a logistic model was calibrated with the presence of SD as the response variable, including variables with clinical or statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R statistical software (v4.2).

The study was developed in accordance to the current norms and regulations for medical research in Colombia (Law 231,981, Resolution Number 8430 1993) and the international ethical standards in clinical research. Each subject included in the study participated voluntarily and gave informed consent (Resolution Number 8430 of 1993). The protocol was approved by the institutional research and ethics committee. The authors certify the veracity and accuracy of the information and report having no conflict of interest or external funding.

ResultsEligible subjects were pre-screened from the medical records of the outpatient clinic. A total of 130 individuals were screened for study entry. 80 subjects were excluded: 44 did not provide informed consent, 18 were undergoing treatment for or had a history of sexual dysfunction, 10 had dementia or a MMSE score <25, and 8 were excluded for clinical reasons determined by the investigators. Ultimately, over a period of 3 years, 50 male patients were included in the study. Recruitment was halted by the investigators due to the slow and challenging process. The mean age of the participants was 63.2 (±9.7) years, 43 (86%) being widowed or single, and 42 (84%) having high school or higher level of education. The most prevalent medical comorbidities were arterial hypertension (84%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) (46%), and dyslipidemia (40%). The use of antidepressants/psychotropics and beta-blockers was noted in 14% and 16% of the subjects, respectively. Based on Beck inventories scores, anxiety or depression was identified in 48% of the participants. The mean scores for the NIHSS, modified Rankin, and VAS for pain for the entire cohort were 6, 1, and 1, respectively. The average time from IS to clinical assessment was 6.5 months (1–90 months) for all 50 subjects. Sexual dysfunction was observed in 18 (36%) of the participants according to the criteria of the ASEX scale, and the mean number of sexual encounters per month was 2±1.75. No case of sexual hyperfunction, defined by an ASEX score <13, was found. A summary of the collected data is shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics by presence of sexual dysfunction.

| Total (N=50) | Sexual dysfunction | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Yes (n=18) | No (n=32) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Widower/single | 43 (86) | 17 (39.53) | 26 (60.47) | .398 |

| Married/Common law | 7 (14) | 1 (14.29) | 6 (85.71) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| None | 1 (2) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | .2375 |

| Primary | 7 (14) | 1 (14.29) | 6 (85.71) | |

| Secondary | 29 (58) | 13 (44.83) | 16 (55.17) | |

| Trade/Technical | 10 (20) | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | |

| University | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | |

| Work status | ||||

| Active | 21 (42) | 4 (19.05) | 17 (80.95) | .068* |

| Inactive | 29 (58) | 14 (48.28) | 15 (51.72) | |

| Prior medical history | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus type 2 | 23 (46) | 11 (47.83) | 12 (52.17) | .189* |

| Hypertension | 42 (84) | 15 (35.71) | 27 (64.29) | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 20 (40) | 6 (30) | 14 (70) | .556 |

| Medication | ||||

| Antidepressants/Psychotropic | 7 (14) | 2 (28.57) | 5 (71.43) | 1 |

| Beta blockers | 8 (16) | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | .694 |

| BDI depression | 15 (30) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | .537* |

| BAI anxiety | 9 (18) | 6 (66.67) | 3 (33.33) | .463 |

| Mean (StDev) | p-value | |||

| Age | 63.22 (9.68) | 67.33 (7.59) | 60.91 (10.01) | .014 |

| BMI | 26.62 (3.22) | 27.49 (3.67) | 26.13 (2.88) | .187 |

| NIHSS | 6.06 (3.33) | 7 (3.66) | 5.23 (2.86) | .144 |

| BDI | 14.06 (7.77) | 15.39 (4.54) | 13.31 (9.08) | .579 |

| ASEX total score | 16.38 (4.66) | 21.39 (2.25) | 13.56 (2.97) | .287 |

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| Time since stroke (months) | 6.5 (5) | 7 (6.75) | 6 (3.5) | .992 |

| Smoking (# cigarrettes) | 0 (4.5) | 0 (5) | 0 (0.75) | .231 |

| Alcohol (# drinks) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.25) | .625 |

| MRankin | 1 (1) | 1.5 (1) | 1 (1) | .554 |

| BAI | 10 (6.75) | 10.5 (5) | 10 (8.25) | .784 |

| Pain VAS | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2.25) | .767 |

| Number of sexual encounters per month | 2 (1.75) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.008 |

StDev: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range. *Chi-squared tests, rest Fisher's exact test.

A total of 32 (64%) subjects did not exhibit SD based on the ASEX scale scores. When compared to the subjects with SD, those without SD were younger (mean age 60.9 years vs. 67.3 years), had a higher prevalence of being married or living with a partner, and a higher rate of employment. Patients without SD had a lower frequency of DM (37.5% vs. 61.1%), a lower incidence of depression (18.7% vs. 50%), and anxiety (9.4% vs. 33.3%). The results for the variables studied in the groups with and without SD are presented in Table 1.

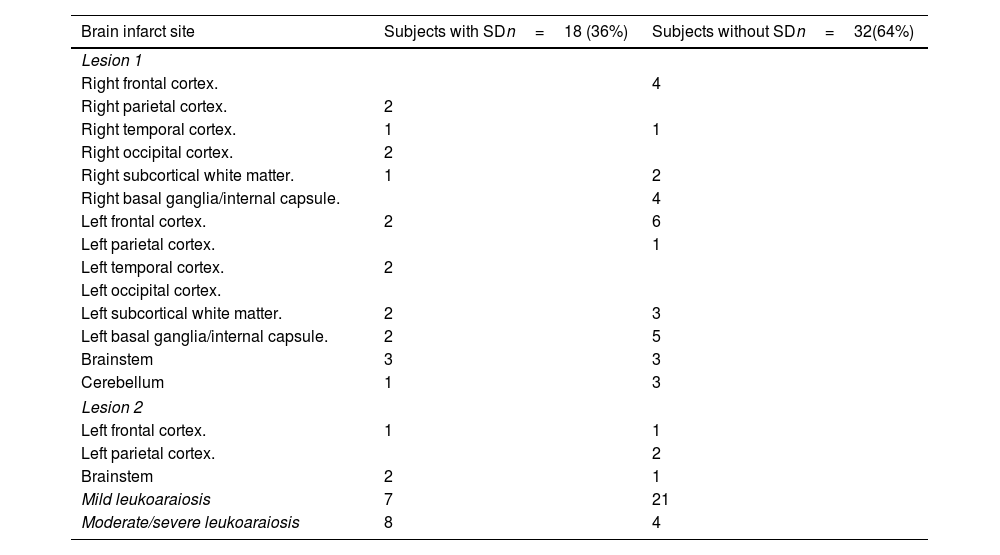

In the multivariate analysis, age (OR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.247) and the location of the ischemic stroke (IS) in the cortico-subcortical region of the parietal, temporal, or occipital lobes (OR 13.59, 95% CI: 1.58–405.784) were found to be associated with SD (Table 2). The detailed description of the brain infarct locations in these patients is presented (Table 3).

Brain infarct site in subjects with and without sexual dysfunction.

| Brain infarct site | Subjects with SDn=18 (36%) | Subjects without SDn=32(64%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion 1 | ||

| Right frontal cortex. | 4 | |

| Right parietal cortex. | 2 | |

| Right temporal cortex. | 1 | 1 |

| Right occipital cortex. | 2 | |

| Right subcortical white matter. | 1 | 2 |

| Right basal ganglia/internal capsule. | 4 | |

| Left frontal cortex. | 2 | 6 |

| Left parietal cortex. | 1 | |

| Left temporal cortex. | 2 | |

| Left occipital cortex. | ||

| Left subcortical white matter. | 2 | 3 |

| Left basal ganglia/internal capsule. | 2 | 5 |

| Brainstem | 3 | 3 |

| Cerebellum | 1 | 3 |

| Lesion 2 | ||

| Left frontal cortex. | 1 | 1 |

| Left parietal cortex. | 2 | |

| Brainstem | 2 | 1 |

| Mild leukoaraiosis | 7 | 21 |

| Moderate/severe leukoaraiosis | 8 | 4 |

Sexual dysfunction (SD) is common in adult males with a history of ischemic stroke (IS). In our study, more than one-third (36%) of the recruited subjects had SD defined by ASEX scale scores. The frequency of sexual encounters in our patients with and without SD ranged from 1 to 2 per month since the IS. Our findings revealed that older age was associated with a higher probability of SD after IS (OR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.247), and SD was associated with parietal, temporal, and occipital lobar ischemic strokes (OR 13.59, 95% CI: 1.58–405.784).

The frequency of SD in stroke patients varies between studies, ranging from 29%14 to 94.8%.15 This variability may be attributed to the different scales used to assess SD, the specific type of SD examined, characteristics of the subjects, cultural factors, and the time elapsed since the stroke.

Sexual activity is influenced by age, health status, and gender. As described by Giaquinto and Akinpelu,7,15 our study also identified age as a determinant of SD after IS. Studies indicate that men experience a decline in sexual function with age with delayed erection, reduced intensity and duration of orgasm, decreased libido, and abnormal ejaculation. Among men aged 75–85 years, only 39% remain sexually active, and the prevalence of SD is 46 cases per 1000 man-years for men aged 60–69 years. Although the mean age of our patients with SD was 67.3 years, higher than the Akinpelu cohort's (mean age of 55 years) and Bugnicourt's cohort (all <60 years), those without SD were 6.4 years younger, similar findings to Akinpelu (59.4 vs. 53.1 years).14,15

The second factor associated with SD in our study was the location of the IS. The relationship between SD and IS location is complex. SD appears to be more prevalent in patients with right hemisphere involvement.16 Subjects with lesions in the right cerebral hemisphere experience decreased sexual desire and frequency of sexual activity. This phenomenon may be attributed to the attentional/activation, emotional, and control functions of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis in the right hemisphere. Erectile dysfunction has been linked to vascular lesions in various locations, including the middle cerebral artery, posterior cerebral artery, basal ganglia, brain stem, thalamus, hypothalamus (paraventricular nucleus and medial preoptic area), midbrain, amygdala, and hippocampus. Specifically, left basal ganglia lesions have been associated with decreased libido, while right cerebellar lesions have been associated to ejaculatory dysfunction.3,17,18 Moreover, it appears that a greater number of ISs increases the likelihood of SD. The evidence regarding the relationship between SD and IS location is inconclusive, with studies showing mixed and sometimes contradictory results. This complexity arises from the multifaceted nature of sexual function (including libido, erection, ejaculation, and satisfaction), the involvement of multiple neural networks, and the influence of external factors.17,18

SD has multiple risk or causal factors, and it is impossible to determine the weight of each of them.19,20 Studies on SD in patients with IS have shown a complex interaction between psychological and biological factors. In the former, the most frequently described factors include depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, low self-esteem, attitudes towards the patient's sexuality, and partner. In the latter, the most frequently described factors include diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, obesity, the severity and type of neurological deficit, time since IS, medications, and location of IS. Additionally, some authors include age, marital status, education level, and employment status among the factors related to SD in patients with IS.8,10 Our patients without SD showed a higher frequency of being married or living with a partner and employment, and a lower prevalence of diabetes, depression, and anxiety. However, in the multivariate analysis, no other associations were identified except for age and IS location. Furthermore, it is not known whether the marital status of the patients in the included sample is representative of the general population. This uncertainty arises after conducting a search in the database of the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) without finding epidemiological data on the marital status of men during the years in which the present study was conducted.

Our investigation focused on SD in men with ischemic stroke brain infarct type. A comprehensive assessment of several aspects related to SD was performed, and validated scales for IS and SD were used. However, there are several limitations: The number of subjects included was small and the projected sample size was not reached, it is a cross-sectional cohort study with no follow-up, patient's psychological factors, and partner factors were not studied, the relationship of SD with quality of life was not assessed, and specific factors related to erectile dysfunction and lubrication were not studied. Additionally, there might be recall bias and reservations about intimacy with the self-applied ASEX scale, as well as participation bias in the study by including only subjects with better self-esteem, sexual function, quality of life, and less neurological deficit.

SD in IS patients is a frequent phenomenon, often overlooked by the patient, partner, and family, with repercussions on the quality of life. Age and location of IS are factors related to its prevalence. However, SD in patients with IS is multifactorial with multiple social, psychological, and biological causes. Despite its complexity, sexual function should be explored in IS patients and physicians should offer, pharmacological and non-pharmacological, therapeutic options for those with SD as an integral part of rehabilitation.

ConclusionSexual dysfunction (SD) is common and frequently overlooked in ischemic stroke (IS) patients. Age and location of the IS are factors that may contribute to its higher prevalence. However, SD in these patients is a complex phenomenon influenced by a combination of psychological, social, and biological factors. It is important to assess sexual function in all stroke patients as an integral component of their rehabilitation process.

Within the limitations of our study, it is worth noting that we had a relatively small number of patients. Obtaining detailed information about their health before and after the stroke was not possible due to follow-up difficulties. Additionally, the absence of an accessible database in our country made it tricky to retrieve epidemiological data for comparison. Further studies are needed to enhance knowledge in this area.

FundingThe authors declare that they did not receive any funding or research grants for the conduct of this study.

Patient consentThe authors declare that all patient data appearing in this article have been obtained with prior informed consent.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that all patient data appearing in this article have been obtained with prior informed consent.