This work evaluates clinical-standard semantic memory assessments in monolingual Spanish-speaking Colombian adults with and without aphasia, addressing 2 aims: (1) to examine whether event semantic memory is related to object and action semantic memory performance; and (2) to explore whether clinical-standard semantic memory assessments can distinguish between Colombian adults with and without aphasia.

MethodsObject, action, and event semantic memory clinical assessments were used evaluate 16 adults with aphasia and 16 matched controls from Colombia. Bayesian linear mixed-effects models were used to examine the 2 specific aims.

ResultsFirst, results replicated and extended findings that object and action deficits may contribute to event semantic memory impairments in aphasia. Second, results suggested that clinical-standard semantic memory assessments may distinguish between people with and without post-stroke aphasia in a Colombian sample.

ConclusionThis work identifies the need to continue developing sociolinguistically sensitive neuropsychological assessments, which are critical for establishing valid cognitive models and improving clinical diagnostics and treatments in diverse populations of stroke survivors.

Este trabajo busca examinar evaluaciones clínicas de memoria semántica en adultos monolingües hispanohablantes colombianos con y sin afasia. Se describen dos objetivos: (1) examinar si la memoria semántica de eventos se relaciona con la memoria semántica de objetos y acciones; y (2) explorar si las evaluaciones clínicas de memoria semántica pueden distinguir entre adultos colombianos con y sin afasia.

MétodosSe utilizaron evaluaciones clínicas de memoria semántica de objetos, acciones y eventos en 16 adultos con afasia y 16 controles de Colombia. Se utilizaron modelos bayesianos lineales de efectos mixtos para examinar los dos objetivos específicos.

ResultadosPrimero, nuestros resultados replican y amplían hallazgos previos que indican que los déficits de memoria semantica de objetos y acciones contribuyen a las alteraciones de la memoria semántica de eventos en personas con afasia. Segundo, nuestros resultados sugirieren que las evaluaciones de memoria semántica clínica pueden distinguir entre personas con y sin afasia en una muestra colombiana.

ConclusiónEste trabajo resalta la necesidad de desarrollar evaluaciones neuropsicológicas que sean sociolingüísticamente apropiadas. Estas evaluaciones son críticas para establecer modelos cognitivos válidos para cada población, y para mejorar el diagnóstico y tratamiento de poblaciones diversas con afasia, sobrevivientes de accidentes cerebrovasculares.

Semantic memory is a type of explicit, declarative long-term memory that stores knowledge extending beyond specific and autobiographical experiences to include general facts (e.g., Australia is south of the equator), word meanings, and object and action information (e.g., swimming is typically done in water).1 Semantic memory not only contains knowledge about objects and actions but also about events. Events involve world knowledge of associated objects, actions, and contexts that commonly co-occur.2–4 For example, semantic memory for events might include knowledge that an action of measuring by a baker would likely involve flour and take place in a kitchen, whereas measuring by a carpenter likely involves wood and takes place in a workshop.4,5 Event representations are thus complex and multidimensional: they connect multiple types of semantic-memory representations, including actions and objects.6

Semantic memory is the starting point for language production and is critically accessed during language comprehension at the word, sentence, and discourse levels.5 It may also serve as the basis for efficacious language treatment for aphasia.7,8 This makes the assessment of semantic memory function critical in patients with post-stroke aphasia. There are clinically established assessments of semantic memory for both objects (Pyramids and Palm Trees [PPT]9) and actions (Kissing and Dancing Test [KDT]10). These assessments use line-drawing pictures and ask participants to make judgments about the relationships among depicted objects or actions. Notably, no words are used in the assessments, only images, removing the need for translations to other languages. Furthermore, these assessments are sensitive to the presence and severity of semantic-memory impairments across a number of neurologically impaired populations, including post-stroke aphasia.10,11 However, a measure of semantic memory for events is not clinically available, despite recent efforts3 to develop such measures (see discussion below).

Event, action, and object knowledge stored in semantic memory are contingent on a person's perceptual, linguistic, and interactive experience with the world.1,12 Therefore, the content of semantic memory may vary based on cultural and linguistic differences. There is preliminary evidence that cultural and linguistic differences affect performance on clinical-standard measures of object- and action-related semantic memory (PPT and KDT), requiring culture-specific norming efforts.13–16 There is also preliminary evidence for cross-linguistic and cross-cultural variability in event representations. Specifically, the co-occurrence between objects, actions, and contexts that make up event representations may differ across cultures, and event representations may also differ across languages, with different lexical–structural encoding of elements like space, number, motion, and event structure.16 Sociolinguistic differences in object, action, and event representations have not been systematically examined to date, nor has their association with the presence of language disorders such as aphasia.

Given potential differences in semantic memory across sociolinguistic backgrounds, it is possible that clinical assessments and cognitive findings from English-speaking samples may not be similar in speakers of other languages. This research serves as a preliminary investigation to assess semantic memory in monolingual Spanish-speaking Colombian adults with and without post-stroke aphasia. In particular, we seek to replicate findings from Dresang et al. (2019), which to our knowledge, has been the only study to directly compare performance across object-, action-, and event-related semantic memory and relate this to the presence of post-stroke aphasia. We investigate whether 2 major findings from this work extend to a sample of adults with a distinct sociolinguistic background—monolingual Spanish-speakers from Colombia.

First, Dresang et al.,3 found that performance on both object and action semantic-memory clinical assessments reliably predicted event semantic memory performance. Consistent with theoretical models of event representations,4–6 these results indicate that semantic memory for events reflects a confluence of object and action knowledge.3Therefore, the first objective of the current research was to assess the reproducibility of these findings by examining whether event semantic memory is associated with object and action semantic-memory performance in Colombian adults with aphasia. Because this finding reflects the structure underlying semantic memory domains, we predicted that the findings reported in Dresang et al.3 should hold true for adults with a Colombian sociolinguistic profile.

Second, Dresang et al.,3 found that clinical-standard semantic memory assessments for objects, actions, and events distinguished neurologically impaired adults from matched neurotypical controls. This finding replicated evidence supporting that clinical-standard measures for object-related (PPT9) and action-related semantic memory (KDT17) can distinguish between individuals with and without neurological impairments, such as aphasia.10,11 Moreover, Dresang and colleagues extended this evidence by finding that event semantic memory reliably differentiated individuals with aphasia from matched neurotypicals as well. Although this finding is consistent with the hypothesis that access to semantic memory is associated with language performance,1,12 it remains unclear to what extent cultural and linguistic differences may affect the relationship between semantic memory and aphasia. Therefore, the second objective of our research was to investigate whether clinical-standard semantic memory assessments for objects, actions, and events distinguished neurologically impaired adults from matched controls in Colombia. Given that semantic memory and event representations, in particular, may be subject to significant sociolinguistic variability,16 there may be differences in the ability of different semantic-memory measures (for objects, actions, and events) to detect the presence of neurological impairment.

AimsThe current study addresses 2 research questions: (1) whether event semantic memory is related to object and action semantic-memory impairments in Colombian adults with aphasia, as previously found for English-speaking people with aphasia3; and (2) whether each of the semantic-memory measures (action, object, and event) can distinguish between people with and without aphasia in a Colombian sample.

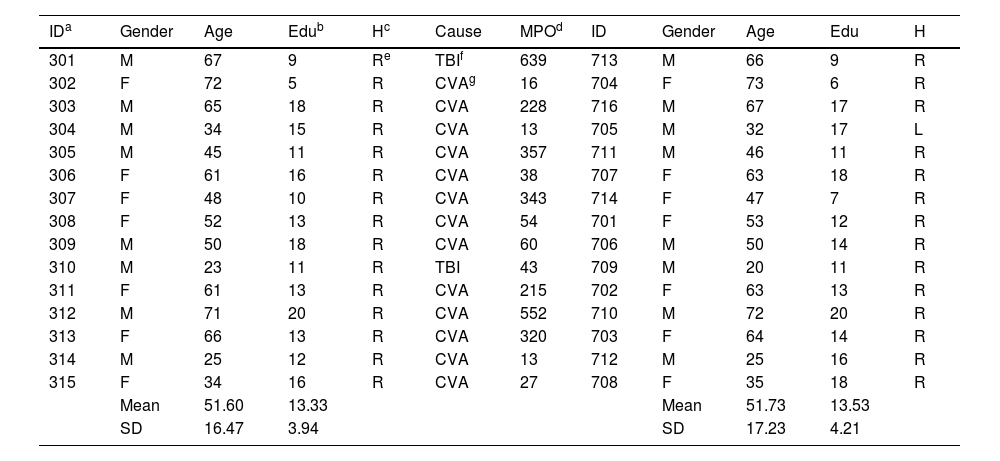

MethodsParticipantsParticipants were recruited in Bogotá, Colombia from local collaborating institutions. Local clinicians referred individuals with an existing diagnosis of post-stroke aphasia. Sixteen persons with chronic aphasia and 16 age-, gender- and education-matched controls participated in this study. See Table 1 for demographic information. All participants passed screenings to rule out frank visual, memory, and hearing deficits (line bisection and recognition memory subtests from the Comprehensive Aphasia Test19; and an audiometric screening at 40 dB at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz).

Matched participants’ demographic information.

| IDa | Gender | Age | Edub | Hc | Cause | MPOd | ID | Gender | Age | Edu | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301 | M | 67 | 9 | Re | TBIf | 639 | 713 | M | 66 | 9 | R |

| 302 | F | 72 | 5 | R | CVAg | 16 | 704 | F | 73 | 6 | R |

| 303 | M | 65 | 18 | R | CVA | 228 | 716 | M | 67 | 17 | R |

| 304 | M | 34 | 15 | R | CVA | 13 | 705 | M | 32 | 17 | L |

| 305 | M | 45 | 11 | R | CVA | 357 | 711 | M | 46 | 11 | R |

| 306 | F | 61 | 16 | R | CVA | 38 | 707 | F | 63 | 18 | R |

| 307 | F | 48 | 10 | R | CVA | 343 | 714 | F | 47 | 7 | R |

| 308 | F | 52 | 13 | R | CVA | 54 | 701 | F | 53 | 12 | R |

| 309 | M | 50 | 18 | R | CVA | 60 | 706 | M | 50 | 14 | R |

| 310 | M | 23 | 11 | R | TBI | 43 | 709 | M | 20 | 11 | R |

| 311 | F | 61 | 13 | R | CVA | 215 | 702 | F | 63 | 13 | R |

| 312 | M | 71 | 20 | R | CVA | 552 | 710 | M | 72 | 20 | R |

| 313 | F | 66 | 13 | R | CVA | 320 | 703 | F | 64 | 14 | R |

| 314 | M | 25 | 12 | R | CVA | 13 | 712 | M | 25 | 16 | R |

| 315 | F | 34 | 16 | R | CVA | 27 | 708 | F | 35 | 18 | R |

| Mean | 51.60 | 13.33 | Mean | 51.73 | 13.53 | ||||||

| SD | 16.47 | 3.94 | SD | 17.23 | 4.21 |

SD = standard deviation.

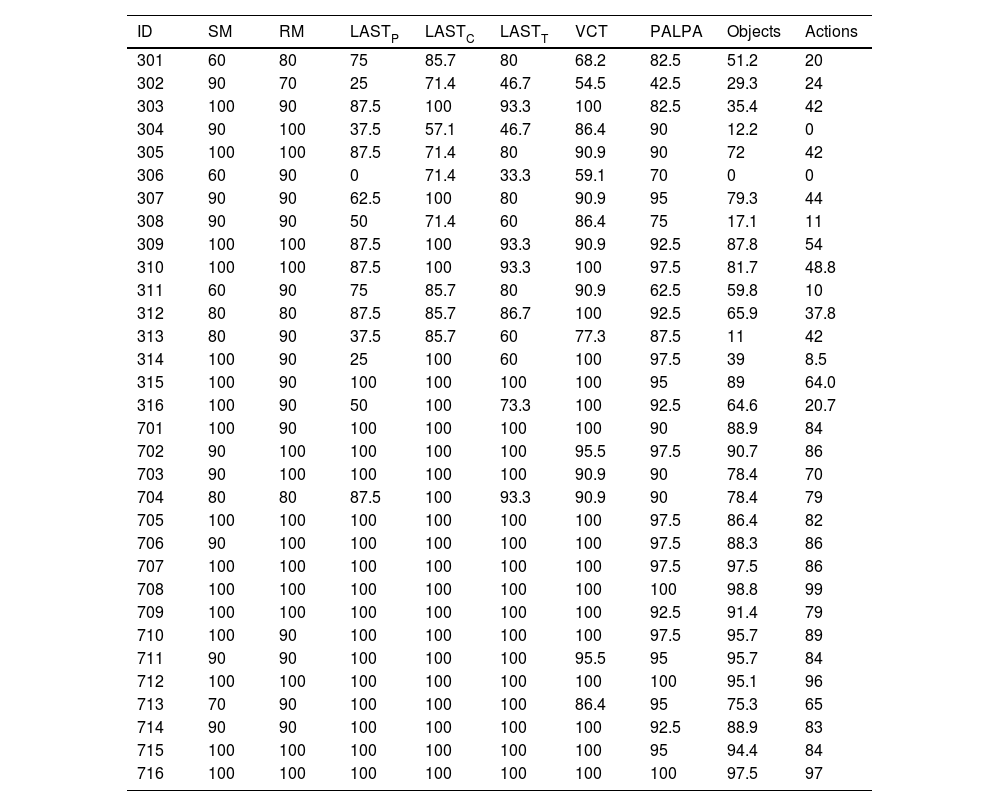

Participants with aphasia had diagnoses of fluent aphasia, established by the Colombian-certified Speech and Language Pathologists who referred them. To confirm the presence of aphasia in stroke participants and the absence of aphasia in neurotypical controls, all participants completed a Spanish version of the Language Screening Test (LAST20). The LAST includes a short assessment of naming, repetition, automatic speech, and auditory comprehension of words and sentences. LAST was chosen given resource and time limitations to complete the battery of language and semantic memory assessments in Colombia. To further assess language impairments in participants with aphasia, a language battery of noun and verb naming and comprehension was administered.21,22 See Table 2 for language assessment performance.

Performance in language assessments.

| ID | SM | RM | LASTP | LASTC | LASTT | VCT | PALPA | Objects | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301 | 60 | 80 | 75 | 85.7 | 80 | 68.2 | 82.5 | 51.2 | 20 |

| 302 | 90 | 70 | 25 | 71.4 | 46.7 | 54.5 | 42.5 | 29.3 | 24 |

| 303 | 100 | 90 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.3 | 100 | 82.5 | 35.4 | 42 |

| 304 | 90 | 100 | 37.5 | 57.1 | 46.7 | 86.4 | 90 | 12.2 | 0 |

| 305 | 100 | 100 | 87.5 | 71.4 | 80 | 90.9 | 90 | 72 | 42 |

| 306 | 60 | 90 | 0 | 71.4 | 33.3 | 59.1 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| 307 | 90 | 90 | 62.5 | 100 | 80 | 90.9 | 95 | 79.3 | 44 |

| 308 | 90 | 90 | 50 | 71.4 | 60 | 86.4 | 75 | 17.1 | 11 |

| 309 | 100 | 100 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.3 | 90.9 | 92.5 | 87.8 | 54 |

| 310 | 100 | 100 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.3 | 100 | 97.5 | 81.7 | 48.8 |

| 311 | 60 | 90 | 75 | 85.7 | 80 | 90.9 | 62.5 | 59.8 | 10 |

| 312 | 80 | 80 | 87.5 | 85.7 | 86.7 | 100 | 92.5 | 65.9 | 37.8 |

| 313 | 80 | 90 | 37.5 | 85.7 | 60 | 77.3 | 87.5 | 11 | 42 |

| 314 | 100 | 90 | 25 | 100 | 60 | 100 | 97.5 | 39 | 8.5 |

| 315 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 89 | 64.0 |

| 316 | 100 | 90 | 50 | 100 | 73.3 | 100 | 92.5 | 64.6 | 20.7 |

| 701 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 88.9 | 84 |

| 702 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.5 | 97.5 | 90.7 | 86 |

| 703 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90.9 | 90 | 78.4 | 70 |

| 704 | 80 | 80 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.3 | 90.9 | 90 | 78.4 | 79 |

| 705 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.5 | 86.4 | 82 |

| 706 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.5 | 88.3 | 86 |

| 707 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 86 |

| 708 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.8 | 99 |

| 709 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92.5 | 91.4 | 79 |

| 710 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.5 | 95.7 | 89 |

| 711 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.5 | 95 | 95.7 | 84 |

| 712 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.1 | 96 |

| 713 | 70 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 86.4 | 95 | 75.3 | 65 |

| 714 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92.5 | 88.9 | 83 |

| 715 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 94.4 | 84 |

| 716 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.5 | 97 |

*All values, except for participant ID are given in percentage correct.

ID = participant identification number (300 for PWA, 700 for controls); SM = semantic memory subtest from the CAT; RM = recognition memory subtest from the CAT; LASTP = language production score from the LAST; LASTC = language comprehension score from the LAST; LASTT = LAST total score; VCT = Verb Comprehension Test (VCT) from the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences; PALPA = Spanish adaptation of the Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia number 47; Objects = percentage correct of objects from the Object and Action Naming Battery (OANB); Actions = percentage correct of actions from the Object and Action Naming Battery (OANB).

Semantic memory was assessed using current clinical-standard tests. To assess object- and action-related semantic memory, participants were given the Pyramids and Palm Trees (PPT9) and the Kissing and Dancing Task (KDT17), respectively. The PPT has norms for neurotypical Spanish speakers from Spain and Argentina.14,23,24 KDT does not have established norms in Spanish, but it has been adapted to meet the needs of non-English populations.15 For both PPT and KDT, participants viewed images on a computer screen and indicated which of 2 images went best with a reference picture. Participants pressed buttons on a computer keyboard that corresponded to images displayed on the left- or right-hand side of the screen. There were 3 practice trials and 52 experimental trials for each of these assessments.

To assess event-related semantic memory, participants were given the Event Task.3 Participants viewed a naturalistic colored photograph on the computer screen and indicated whether each scene was something that “might normally happen”. Participants pressed buttons on a laptop keyboard labeled “yes” and “no”. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible and were provided 5 s to respond before the program continued to the next trial. There were 4 practice trials and 256 experimental trials, which were separated by a halfway break. Additional Event Task details, including development and norming, are reported in Dresang et al.,3 and the complete stimulus set is located at https://osf.io/pzqcj/. All semantic memory assessments were administered on a computer, using E-Prime 2.0.25 Semantic memory assessments and procedures were exact replications of those reported in Dresang and colleagues.3

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh approved this international research. Ethical approval from the partner institutions in Colombia was also obtained (Colombian Institute of Neurosciences and the aphasia support group [EFUNA] sponsored by the National University of Colombia).

AnalysesWe implemented Bayesian generalized linear mixed-effects models using Stan with the BRMS package in the R statistical software version 4.2.2.26–29 We used a Bernoulli probability distribution with a logit link function and weakly informative priors for beta coefficients for all models. Default BRMS priors were used for all other model parameters. We ran 4 Hamiltonian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains, for each model, with 6000 iterations. The initial 1500 chains were used as a warm-up; thus, they were not included in the parameters' estimation. Model convergence was examined using the Gelman-Rubin Potential Scale Reduction statistic (̂R), the number of effective samples, and trace plots. Model fit was examined using posterior predictive checks. We have provided details about model convergence, model fit, and comprehensive model results in the supplemental materials.

For research question 1, we used 2 models testing the prediction that event semantic-memory representations reflect action and object knowledge2 in people with aphasia. The first model (action knowledge) used trial-level accuracy in the Event Task as a dependent variable and a fixed effect of mean KDT performance per participant. LAST performance served as a control variable to approximate overall aphasia severity, given that aphasia severity accounts for significant variability in performance for any task.30 Random effects included intercepts for participants and items and random slopes within participants for aphasia severity and KDT performance. The second model (object knowledge) used the same dependent variable as the model above but with a fixed effect of mean PPT performance per participant. Random effects included intercepts for participants and items and random slopes within participants for aphasia severity and PPT performance. All variables (PPT, KDT, and LAST) were scaled and centered around their respective means.

For research question 2, we used 3 models to explore whether assessments of object-, action-, and event-related semantic memory could distinguish between people with aphasia and people without aphasia (age, gender, and education-matched controls). In the first model, we used trial-level accuracy in PPT as the dependent variable and group (PWA vs. controls) as a fixed effect; with controls as a reference value. Random effects included intercepts for participants and items and random slopes within participants for aphasia severity (LAST). In the second model, we used trial-level accuracy in KDT as the dependent variable with the same fixed and random effects structure as the model above. Similarly, in the third model, we used trial-level accuracy in the Event Task as the dependent variable with the same fixed and random effects structure described above. We have provided details of all models in the supplemental materials.

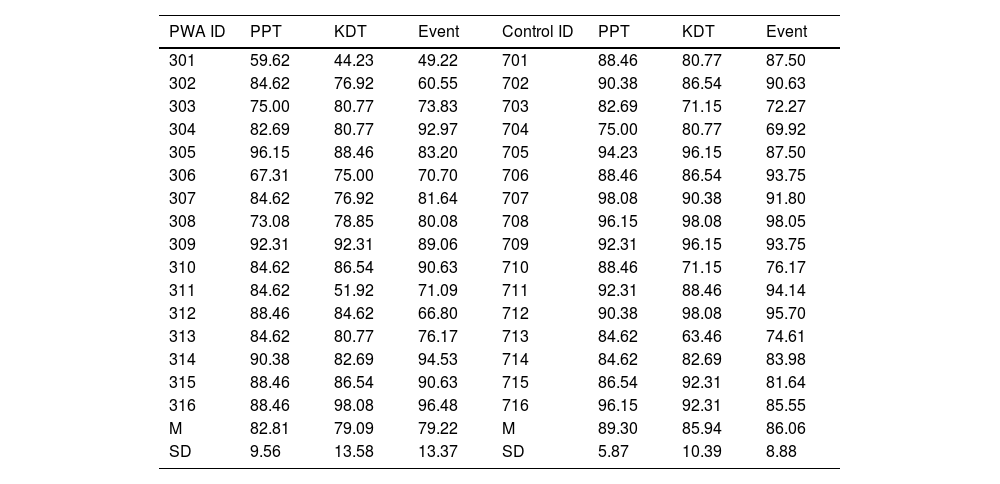

ResultsFor research question 1 regarding the relationship between object, action, and event semantic memory, we found that KDT was a reliable predictor of Event Task performance (β = 0.64, 90% CI: 0.15, 1.28). Although PPT was not a reliable predictor of Event Task performance (β = 0.45, 90% CI: −0.04, 0.93), there was evidence of positive effects when examining its posterior distribution. Specifically, 94% of the posterior distribution for this effect was greater than zero. This provides weak but positive evidence that PPT is associated with Event Task performance. Together, these results provide preliminary evidence that better access to object and action semantic memory may be associated with better Event Task performance in Colombian people with aphasia. Semantic memory performance for all participants is reported in Table 3.

Performance on semantic-memory assessments.

| PWA ID | PPT | KDT | Event | Control ID | PPT | KDT | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301 | 59.62 | 44.23 | 49.22 | 701 | 88.46 | 80.77 | 87.50 |

| 302 | 84.62 | 76.92 | 60.55 | 702 | 90.38 | 86.54 | 90.63 |

| 303 | 75.00 | 80.77 | 73.83 | 703 | 82.69 | 71.15 | 72.27 |

| 304 | 82.69 | 80.77 | 92.97 | 704 | 75.00 | 80.77 | 69.92 |

| 305 | 96.15 | 88.46 | 83.20 | 705 | 94.23 | 96.15 | 87.50 |

| 306 | 67.31 | 75.00 | 70.70 | 706 | 88.46 | 86.54 | 93.75 |

| 307 | 84.62 | 76.92 | 81.64 | 707 | 98.08 | 90.38 | 91.80 |

| 308 | 73.08 | 78.85 | 80.08 | 708 | 96.15 | 98.08 | 98.05 |

| 309 | 92.31 | 92.31 | 89.06 | 709 | 92.31 | 96.15 | 93.75 |

| 310 | 84.62 | 86.54 | 90.63 | 710 | 88.46 | 71.15 | 76.17 |

| 311 | 84.62 | 51.92 | 71.09 | 711 | 92.31 | 88.46 | 94.14 |

| 312 | 88.46 | 84.62 | 66.80 | 712 | 90.38 | 98.08 | 95.70 |

| 313 | 84.62 | 80.77 | 76.17 | 713 | 84.62 | 63.46 | 74.61 |

| 314 | 90.38 | 82.69 | 94.53 | 714 | 84.62 | 82.69 | 83.98 |

| 315 | 88.46 | 86.54 | 90.63 | 715 | 86.54 | 92.31 | 81.64 |

| 316 | 88.46 | 98.08 | 96.48 | 716 | 96.15 | 92.31 | 85.55 |

| M | 82.81 | 79.09 | 79.22 | M | 89.30 | 85.94 | 86.06 |

| SD | 9.56 | 13.58 | 13.37 | SD | 5.87 | 10.39 | 8.88 |

*All values, except for participant ID are given in percentage correct.

ID = participant identification number (300 for PWA, 700 for controls); PPT = Pyramids and Palm Trees; KDT = Kissing and Dancing Test; Event = Event Task; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation.

For research question 2, group reliably predicted trial-level accuracy on PPT (β= −0.57, 90% CI: −1.03, −0.11), with participants with aphasia performing worse than controls. Group did not reliably predicted trial-level accuracy on KDT (β= −0.63, 90% CI: −1.25, 0.01) or the Event Task (β= −0.47, 90% CI: −0.01, 0.08); however, there was evidence of positive effects when examining their posterior distributions. Specifically, 95% and 92% of the posterior distributions for group predicting KDT and the Event Task, respectively, were below zero. These results provide weak but positive evidence that participants with aphasia performed worse than controls in both of these assessments. Taking these results into consideration, we provide preliminary evidence that PPT, KDT, and the Event Task could each distinguish between people with and without aphasia in the Colombian context. However, these findings require additional examination and replication.

DiscussionThis work examined semantic memory performance in a group of Colombian adults with post-stroke aphasia and age-matched neurotypical controls to address 2 research questions. First, this study investigated the relationship of impaired performance across domains of semantic memory, examining whether event knowledge impairments were related to action- and object-knowledge impairments, as has previously been found in a sample of English-speaking US stroke survivors with aphasia.3 Second, this study evaluated whether assessments of object-, action-, and event-related semantic memory could distinguish between people with and without aphasia in monolingual Colombian Spanish-speaking adults. This preliminary work provides a step toward developing sociolinguistically sensitive models of cognitive impairments and assessment measures for diverse patient populations.

The current results are largely consistent with previous findings that performance on object- and action-related semantic memory can independently predict event semantic memory performance in adults with aphasia. We found that stronger action semantic performance was robustly associated with stronger event semantic memory. We also found weak, but positive evidence that object semantic memory was associated with event semantic memory. This broadly replicates findings from the same assessment measures used in adults with aphasia in the USA: Dresang and colleagues3 found that both PPT and KDT performance predicted Event Task performance in 26 English-speaking adults with chronic stroke aphasia. If replicated and further examined, these results would support the hypothesis that event representations reflect a combination and possible binding of object and action semantic knowledge.2,3,6 As such, specific variations in world knowledge may not be expected to influence general interactions between object, action, and event domains of semantic memory. However, future work is still required to thoroughly evaluate the contributions of sociolinguistic variations in semantic memory.

In addition, this study offers preliminary evidence suggesting that different semantic-memory measures may distinguish between people with and without aphasia in Spanish-speaking Colombian adults. We found that participant group status reliably predicted performance on object-related semantic memory, but action- and event-related semantic memory did not. However, the posterior distributions provide weak but positive evidence suggesting that all 3 semantic memory assessments could be sensitive to the presence of aphasia, which is consistent with previous findings in monolingual English-speaking adults in the USA.3 Given the semantically rich and experience-driven nature of event knowledge, it is possible that compared to objects, event semantic memory may be susceptible to greater variation across individuals of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds.16,33 Thus, action and event semantic memory measures that are more sociolinguistically appropriate to the target population might improve reliability in distinguishing between Colombian adults with and without aphasia. Additional research is required to characterize sociolinguistic similarities and differences in semantic memory and to establish clinical assessments that are sensitive to semantic memory impairments in diverse patient populations.

There remains a lack of assessments with appropriate psychometric properties that measure semantic memory in Spanish speakers with aphasia, particularly in Latin American countries. More broadly, very few aphasia tests have been standardized and normed in languages other than English, which challenges the reliability and validity of these measures when applied to diverse populations.18 This study takes an important first step in examining semantic memory assessments in monolingual Spanish-speaking Colombian adults with and without aphasia. As a preliminary investigation, this work is limited by a non-standardized translation of the LAST and modest sample sizes. Future work should use a Spanish-normed assessment of aphasia severity and pursue larger sample sizes in this and other Latin American groups. As mentioned above, culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment adaptations are also required. Overall, it is crucial to continue to pursue adaptations of aphasia assessments and treatments to multiple languages.

ConclusionThe current study replicated and extended previous findings that object and action deficits contribute to event memory impairments in aphasia. Furthermore, the current findings provided preliminary evidence that clinical-standard semantic memory assessments could distinguish between Colombian adults with and without aphasia, but further examination is required. This work underscores the need for culturally and linguistically appropriate adaptations of neuropsychological tests so that clinical advancements can reach broader patient populations in Spanish-speaking Latin American communities.

Informed consentThis work involved the use of human subjects. All work described herein has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. All subjects had comprehension sufficient to understanding study demands and participation involvement. Informed consent was obtained, and privacy rights of human subjects were observed in accordance with the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approval.

Ethical considerationsThe Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Pittsburgh approved this international research. Ethical approval from the partner institutions in Colombia was also obtained (Colombian Institute of Neurosciences and the aphasia support group [EFUNA] sponsored by the National University of Colombia). All work was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Funding and acknowledgmentsThis research was supported by the Tinker Summer Field Research Grant from the Center for Latin American Studies (University of Pittsburgh) awarded to Yina Quique. It was also supported by the Stanley Prostrednik Health Sciences Grant from the University of Pittsburgh‘s Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Programs awarded to Haley Dresang. The authors are grateful to the Instituto Colombiano de Neurociencias (Dr. Jorge Eslava) and the EFUNA team at Universidad Nacional de Colombia.