The main objective of this article is to present an analysis of 20 years of the North America Free Trade Agreement (nafta) in the area of cultural policies, specifically, those related to cultural industries. Our main focus is to compare the positions that the Canadian and Mexican governments have taken vis-à-vis the world’s number-one audiovisual power, the United States. Within this scenario, we have spotlighted the Mexican case.

El objetivo principal de este artículo es presentar un análisis de los veinte años del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (tlcan) en el área de políticas culturales, específicamente las relacionadas con las industrias culturales. Nuestro enfoque se centra en comparar las posturas que los gobiernos canadiense y mexicano han tenido frente a Estados Unidos, el poder audiovisual nùmero uno del mundo. Dentro de este escenario hemos destacado el caso de México.

In theoretical terms, we consider cultural industries goods and services that have a higher symbolic value than their practical use, as they are sources of communication, entertainment, artistic appreciation, and information (Scott, 2000). They are also industrial processes, since they are multiplied into tangible or intangible copies for consumers (Bustamante, 2003). With this in mind, we position our study under the political economy of culture approach that examines “the power relations, which mutually constitute the production, distribution, and consumption of resources” (Mosco, 2009: 2), including cultural industries. The political economy tradition has “a strong commitment to historical analysis, to … the study of social value … and, finally, to social intervention and praxis” (Mosco, 1996: 17). Additionally, the political economy foundation on institutional economics has highlighted “the constraints imposed by social custom, social status, and social institutions on all behaviour, including market behaviour” (Mosco, 2009: 52). For those reasons, it is an appropriate approach for studying industrial development and cultural policies under the social framework of a free trade agreement.

We conducted a historical and critical analysis to identify the different ways in which nafta members have addressed cultural industries, specifically, in terms of the different configurations between public intervention and private enterprise (Golding and Murdock, 2000: 72).

Consistent with the political economy of culture approach, we employed a critical realist methodology, which is based on the assumption that although “objective reality” is unattainable, through a critical examination, it is possible to “get empirical feedback from those aspects of the world that are accessible” (McEvoy and Richards, 2006: 69). This methodology combines analyses of qualitative and quantitative data, as well as original and secondary data (that is, from previous research) (Cohen and Crabtree, 2006). To collect the data, we drew on previous research, official statistics, and media reports as well as original document analysis and statistical systematizations. This triangulation allowed us to compare different sets of information, to reveal different facets of the topic, and to contextualize it (Cohen and Crabtree, 2006). This research logic allowed us to establish links between cultural public policies and economic indicators.

Our focus on cultural industries acknowledges that they are at the economic core of the cultural sector in each country. This has been especially true over the last two decades, in which cultural industries have grown constantly and more than the average of the other industrial and economic sectors (Hesmondhalgh, 2013). In that context, several countries and international organizations have participated in emerging cultural policy debates regarding how to best address economic growth in relation to culture (Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2005).

At the same time, technological convergence (Murdock, 2003) has important implications for cultural industries’ dynamics, mainly due to the international division of labor through the reshaping of creative jobs, skills’ structures, and labor organizations, but also regarding cultural industries’ distribution and consumption in multiscreen and mobile platforms. This poses major challenges for cultural industries’ policy design.

In addition, our research design draws on compared policy studies that have been categorized as “case-oriented” or “variable-oriented.” In line with the former, we adopt a historical-institutional approach with emphasis on the differences of the cases presented. In accordance with the latter, we also focus on the cases’ similarities to present generalizations (Imbeau et al., 2000). We approached our study from both directions since in this way we can provide a broad critical overview of the topic and, to an extent, establish links among cases.

Finally, it is important to clarify that we think of nafta as an example for understanding cultural policy-making under the specific constraints of free-trade logic. We also infer that similar conditions exist in comparable free-trade government initiatives under prevailing global capitalism.

Overview of nafta MembersSince the North American Free Trade Agreement (nafta) took effect in 1994, a number of disputes have arisen, and different sectors of the three member countries have complained about different issues (Vega, 2005). Nonetheless, economic exchange, investment, and migration flows among the three countries have increased (Weintraub, 2004). During this period, economic interdependence between the United States and Canada as well as between the U.S. and Mexico has increased (Chabat, 2000). However, the Canadian-Mexican trading relationship continues to be of small significance.

Marked inequalities exist among the three nafta countries, especially in socio-economic terms. For example, while in 2009 the gross domestic product per capita in the United States was US$46 360 and in Canada, US$41 960, in Mexico it was barely US$8 960.1 In the same vein, if we consider the United Nations Development Program (undp) human development index, Mexico is ranked number 58, while Canada and the U.S. are in eleventh and third place worldwide, respectively (undp, 2013).

Likewise, important political, demographic, and socio-cultural differences exist among the three nafta countries. Mexico covers nearly 2million km2, with a population of 112million in 2010, making it the most populous Spanish-speaking nation in the world. In addition, Spanish coexists alongside 62 indigenous languages officially recognized by the Mexican state. The population is ethnically composed of 75 percent mestizos (mixed indigenous and European); 12 percent indigenous people; 12 percent of European origin; and the remaining 1 percent of Afro-Mexicans, Asian-Mexicans, and Arabic-Mexicans (inegi, 2010). As for its political system, Mexico is a federal republic considered to be moving toward democratic normality since the second half of the 1990s.

Alternatively, Canada is the world’s second largest country, with an area of 9.9million km2 and a population of 33.74million, 45 percent of British origin, 27 percent of French origin, and the rest from different ethnic backgrounds. Its official languages are English and French. For decades, the Canadian federation has been considered a multicultural country, since it encompasses different ethnic groups from all around the world. Its cultural diversity is reflected mainly in the cities of Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. Canada’s political system is a parliamentary monarchy with a prime minister and is considered to be a consolidated democracy.

Finally, the U.S. has an area of 9.6million km2, making it the world’s third largest nation in terms of territory and also in terms of its population, 308million in 2010. Demographically, it has 63.7 percent European descendants, 12.6 percent Afro-Americans, 4.8 percent of Asian origin, and 0.9 percent Native Americans. The Latino population represents 16.3 percent (50 477million) of the total, most of Mexican origin (about 30million) (Ennis Ríos-Vargas, and Alber, 2011: 2-3). According to the 2010 census, English, which is the official language, is predominant, although Spanish is spoken by more than 28million people in households and the workplace (Ennis Ríos-Vargas and Alber, 2011). As a result, there is a significant market potential for cultural industries in Spanish. In addition, large U.S. cities like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Miami, Philadelphia, and Boston are considered cosmopolitan metropolises because they are home to a large number of immigrants from all around the world.

The U.S. political system is a federal constitutional republic with a president. Like Canada, it is considered a consolidated democracy.

This brief overview of the three nafta member states gives us a basic backdrop for the differences and asymmetries posed by each nation’s specific characteristics and the complexities they give rise to within the trade agreement.

nafta’s BackgroundWe shift the focus now to cultural policy in Mexico, which before the signing of nafta became a field of significant debate. This was mainly due to the fact that the Mexican government never resorted to the cultural exception clause that the Canadian government had incorporated into the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (fta) five years before (Mosco, 1990: 46), stating, “Cultural industries are exempted from the provisions in this agreement” (Article 2005 [1]). Therefore, by excluding cultural industries from the free flow of merchandise and investments, Canadians were able to partially protect them (Bonfil Batalla, 1992: 159).

It is important to remember that the fta was promoted in the 1980s by the U.S. Republican administration and President Ronald Reagan, who proposed a new relationship between North American countries. This tactic was especially designed to rehearse the U.S. American project to have more influence in the world economy (Mosco, 1990). In other words, this agreement was based on the commercial and political direction that the U.S. would promote later on in international trade agreements like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (gatt) –in the Uruguay Round of the World Trade Organization (wto)– in 1993 and nafta in 1994. Those U.S.-designed agreements represented the geopolitical answer to the European Community process of economic integration (Chomsky, 1998).

Vincent Mosco considered the fta a discourse that, “in itself … is a cultural product whose visions and language reflect the culture of [U.S.] American capitalism. Essentially, the fta is a cultural export from the U.S. to Canada, which, if successful, will be exported to other countries” (1990: 45). In this regard, Mosco’s observation proved true over the following years. It is precisely from that perspective that we understand the problems, distortions, and contradictions that have weighed on nafta after 20 years of operation and as the successor to the fta. In other words, given that the objectives, characteristics, and logic of the treaty were not in accordance with the cultural and socio-economic conditions of most of the Mexican people, its effects have been negative for national agricultural and industrial sectors (Gazol, 2004). On the contrary, due to the agreement’s configuration to favor the needs of large multinational companies, it has benefited the transnational export sector in Mexico and big capital in the three countries.

The objective of the Mexican administration under President Carlos Salinas (1988-1994) was to place nafta at the core of its economic project to accelerate Mexico’s modernization through private investment of both domestic and foreign capital. This in turn was expected to create a large number of jobs and improve development levels. In summary, Salinas’s government promoted the idea that the signing of the treaty would open the doors of the “First World” to Mexico (De la Garza and Velasco, 2000).

Designed by the U.S. administration, rooted in the free market logic, and supported by the Mexican government and its business elites (Gómez, 2007), nafta has been the accelerator of the structural changes promoted in Mexico since the beginning of the 1980s (Fernández-Kelly and Massey, 2007).

Nafta itself puts very clear limits on the degree of integration of its member states since the treaty was conceived from an economic trading perspective sustained by neoliberal policies and orchestrated by U.S. expansionist capitalist interests.2 Of course, we should indicate that this frame of reference also includes resistance, struggles, and tensions within the societies of each of the three countries.

To return to the debate around the negotiations about the involvement of cultural industries in the agreement, unlike Canada, the Mexican government rejected the possibility of introducing the cultural exception clause. Its position was that Mexican cultures and identities were sufficiently solid to withstand any foreign cultural influence, especially that of the U.S. In addition, it was thought that having a different language would serve as a natural barrier against foreign product consumption (Gómez, 2007).

By contrast, Mexican academic and cultural groups warned against the treaty’s inclusion of provisions that would directly limit or endanger the domestic capability to defend, consolidate, and promote Mexican cultural identities (Guevara Niebla and García Canclini, 1992; Crovi, 1996).

The arguments demanding the cultural exception went in two directions. On the one hand, they pointed out the economic consequences of competing openly with the world’s most powerful audiovisual industry, that of the U.S.3 On the other hand, they considered the cultural impacts of an increased cultural penetration, translated in the potential imposition of the U.S. American way of life as a model for Mexicans.4 In turn, this would include the resulting risk of being unable to defend, maintain, and promote Mexican identities and sub-cultures (Guevara Niebla and García Canclini, 1992). Nevertheless, despite these considerations, Mexico’s government did not change its position, and within the free trade relations between the U.S. and Mexico, cultural industries were included like any other goods or services.

George Yúdice points out how nafta defined “culture” as a matter of property, through the inclusion of copyrights, patents, registered trademarks, phytogenetic rights, industrial designs, trade secrets, integrated circuits, geographical indicators, codified satellite signals, audiovisual production, etc. (2002: 266). Thus, we could infer that with nafta, “culture” has been framed and shaped within the new strategies of global capitalism.

At the time, this scenario raised the following questions: How would this institutional framework influence the design of cultural policies in Mexico? Would U.S. audiovisual imports to Mexico increase? Would the rise of the distribution and purchase of U.S. films and television programs have negative effects on Mexican cultural industries? What might the consequences be for Mexican cultural industries in terms of employment, investment, and diversity of contents? And in general terms, what would happen to Mexican audiovisual independent production and distribution? These questions were, of course, also relevant for the Canadian case. But the different paths taken by the two governments allow us to compare the advantages and disadvantages of their public policies in terms of economic and cultural consequences.

Cultural Policies in the nafta Countries: Three Diverging Paths. The Non-cultural Policy of the U.S.?U.S. American documents on culture provide an overview of the general U.S. perspective on state non-intervention in cultural production based on the intention to guarantee the right to free expression laid out in the First Amendment (Miller and Yúdice, 2004). The U.S. coordinates its tacit cultural policy underlying the dominant role of private companies and the market as mechanisms of economic coordination (Muñoz Larroa, 2009). For that reason, the U.S. included cultural products like any other merchandise in the nafta and wto negotiations (Pauwels and Loisen, 2003).

At the same time, the U.S. supports its cultural production by means of different private sector agencies and philanthropic associations, through funds, fiscal incentives, and political lobbying abroad. In those terms, U.S. cultural policies have been characterized as “implicit” (Ahearne, 2009; Throsby, 2009). Numerous studies testify to the historical support given to Hollywood by different U.S. administrations (Sánchez Ruiz, 2003; Frau-Meigs, 2002; Wasko, 2003). For instance, the U.S. government has promoted exports as part of the pursuit of national interests from the end of the World War II (Sánchez Ruiz, 2003) to recent years through the wto. This has also been recurring in bilateral free trade agreements signed with Asian and South American nations. The pressure to open markets abroad has generated increasing revenues reinvested in the national production systems.

Frau-Meigs observed the way in which the U.S. has indirectly promoted culture by means of public and private support through 1) fiscal advantages for foundations that are public aid “disguised” as tax breaks or exemptions; and 2) cultural promotion policies implemented at the local community level that go unnoticed because they are not coordinated federally. In other words, cultural support is decentralized and is not systematic. City councils (in Los Angeles, New York, Denver, Philadelphia, Chicago, etc.) are active in cultural action (Frau-Meigs, 2002).

Other examples have been given by Allen Scott (2004), whose study recounted the active U.S. Department of Commerce support for the U.S. film industry. For instance, in the context of the negative economic impact of runaway film and television production (US$34billion) that moves to other locations in the world looking to cut production costs (Muñoz Larroa, 2009; Tinik, 2008; Wasko and Erickson, 2008), a Canadian report analyzed U.S. policy as follows: On the federal level, U.S. President George W. Bush committed to support the [U.S.] American film industry by approving the American Jobs Creation Act [and] in January of 2005, 40 U.S. states established some type of fiscal incentive for productions that choose to work in their regions. The incentives range from tax exemptions on purchases and hotels, rebates of income taxes and other taxes, to direct refunds of production costs.… The governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, considered an initiative to keep filming in California.… It includes a tax incentive program (Canadian Heritage, Arts and Culture, n.d.).

The California legislation reimbursed costs of permits, public property, public employees, and equipment rental. In addition, producers were given a 15-percent credit on the first US$25 000 earned by workers on low-budget productions filming in the state (Ministry of Management Services, British Columbia, 2002).

In other matters, Miller and Yúdice (2004) argue that U.S. governments’ indirect way of promoting cultural policy creates social tensions and very complex problems in the country’s large cities, since policies do not tackle issues of cultural diversity and inequality. In particular, they highlight the lack of coordination by the state to promote the knowledge of the diverse cultures and languages that coexist in the country. Also, these researchers note that “the future of cultural policy regarding the arts will probably intensify the merchandising of culture, reduce the number of institutions dedicated to the arts and will reduce assistance to minorities” (Miller and Yúdice, 2004: 96).

In sum, we argue that despite the fact that the U.S. government does not have a department or ministry dedicated to cultural matters and that its implicit cultural policy is subsumed under other public policies, mainly economic policies, it is active in fostering the internationalization of its cultural industries.

Canada’s “Hybrid” Cultural Policy: Between the British and French TraditionsIn Canada, the state intervenes directly in cultural policy. Canadian researchers Gattinger and Saint-Pierre (2005) identify a “hybrid” form of cultural management with the combination of two traditions, the British5 and the French.6 These are clearly reflected in the policy implementation in two important provinces, Ontario and Quebec. In the hybrid model, the state has the role of an administrator-arbitrator among the different sectors of artistic and creative life (Gattinger and Saint-Pierre, 2005). Sometimes, the model can lean more toward the French tradition, which means that the state, as the articulator of culture, would intervene more. In the British approach, to the contrary, the state actively assists the cultural needs of civil society. The implementation of one tradition or the other, say the authors, depends on which party or coalition is in power. This hybrid form of cultural policy focuses mainly on the following aspects: freedom of creation and expression, democratization of culture, cultural education, cultural rights, the preservation of heritage resources, and, more recently, on cultural diversity and social cohesion (Gattinger and Saint-Pierre, 2005: 343).

The Canadian position in its bilateral fta with the U.S., and later in nafta, reflected a position much closer to the French custom, where the state has a central role in cultural planning, articulating, promoting, and even protecting heritage. In addition, the Canadian communications system is characterized as a “mixed” model with a strong public broadcasting system7 and private networks (Raboy, 1990).

The free trade conditions proposed by the U.S. demanded changes to the regulation of the public media system in Canada and, what is more, they challenged the role that cultural industries play for Canadians.8 However, in Canada, broadcasting was considered an instrument of production and dissemination that should contribute to the maintenance and development of Canadian culture and its different components (Tremblay, 1992; Taras, Bakardjieva, and Pannekoek, 2007).

The position of the French-speaking province of Quebec has enriched the debate on Canadian cultural policy, on both the federal and the provincial level, because of the role of the state as a central actor for cultural planning, organization, and articulation. In addition, the Quebec government actively fosters cultural activities, both through financing and subsidies, as well as by screening quotas for Quebec’s cultural products. British Columbia is another province that has stood out on a par with Ontario and Quebec in the last decade for enacting policies aimed at promoting culture. In fact, this western Canadian province has shown the largest growth both in audiovisual production and in the economic windfall from that sector. As indicated by several Canadian and U.S. scholars, this is a reflection of an integration of the Vancouver area with the complex structure of Hollywood production (Tinic, 2008; Newman, 2008); the area has even been called Hollywood North.9

In this regard, we point out the autonomy and dynamism that Canadian provinces are imprinting on their cultural sector, emphasizing cultural policies as key to the promotion of cultural industries.

As an example of Canadian cultural policy in the year 2000, the minister of Canadian heritage announced a new filmmaking policy in the document “From Script to Screen: New Policy Directions for Canadian Feature Film.” Its objective was to build an audience for Canadian products. The ambitious goal was to reach five percent of national ticket sales within five years. It should be noted that some European films are considered successful if they have a 25- or 30-percent share of their screens (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004). The broad objectives were 1) to develop and maintain professional creative staff and producers; 2) to restructure programs to assist and increase budgets to promote the quality and diversity of Canadian films; 3) to build a domestic audience through the marketing and promotional support for national films; and 4) to preserve and disseminate the archive of Canadian films (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004).

The Canada Feature Film Fund implemented the program with a budget of US$100million. Financial resources were specifically allocated for a series of assistance programs for screenwriting, project development, marketing support for distributors, a program to complement activities to further participation in the international and national festivals, and aid in creating cooperatives for independent productions (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004). This example illustrates how Canadian federal authorities support a disadvantaged sector that needs to be leveraged though concrete programs to be able to grow its domestic market.

In addition, another important strategy for the Canadian audiovisual sector is the proliferation of joint ventures with U.S. companies to produce audiovisual content in Canada. With this strategy, supported as part of cultural policy, Canada became the second largest exporter of audiovisual products after the U.S. (Tinic, 2010: 99). However, Tinic argues “that these types of international co-productions are marked by their tendency to follow established Hollywood television formulas and set their stories in [U.S.] American cities although they are usually filmed in Vancouver or Toronto. They qualify as Canadian content through the citizenship of the key creative participants in the production agreement” (2010: 100).

In 2007, the cultural sector’s direct contribution to the Canadian economy reached US$36.74billion and it employed 534 325 workers. In 2009, in the midst of the economic recession, the Canadian cultural sector economic impact accounted for US$39billion or 3.1 percent of gdp and it employed 539 000 people, contributing to the creation of more than one million direct and indirect jobs (The Conference Board of Canada, 2010).

Cultural Policies in Mexico: Ranging between Paternalism and ArbitrationIn Mexico, cultural policies have been subject to the good will and discretionary policies of the president or minister of public education in office. As a result, the Mexican state lacks a long-term project for the cultural sector. Paradoxically, the Mexican delegation participating at unesco sessions has been very active in discussions and declarations (Arizpe, 2006).

Cultural policy management is centralized by the federal government through the Ministry of Public Education, which has a paternalistic vision reinforced by the lack of mechanisms for civil society to actively participate in the design and monitoring of public cultural policies (García Canclini, 2002; Nivón, 2004).

In the second half of the twentieth century, Mexican cultural policy concentrated mainly on three fundamentals: safeguarding, promotion, and dissemination of the historical and cultural heritage through two large institutions, the National Fine Arts Institute and the National Institute of Anthropology and History. At the moment, these two agencies belong to a centralizing institution, the National Council for Culture and the Arts (Conaculta). This agency was founded in 1989 to modernize and coordinate cultural institutions in organizing the cultural sector. Up until then, the different cultural agencies had been directly managed by the Ministry of Public Education’s Department of Culture (Ramos, 2007).

At its foundation, Conaculta outlined the following objectives: a) to strengthen national identity; b) to promote and guarantee respect for freedom of creation; and c) to guarantee access of more Mexicans to cultural goods and services (Tovar y de Teresa, 1994: 18). Accordingly, cultural policy in Mexico has followed those directives and, in theory, stayed within their lines of action; the council attempted to implement cultural pluralism, freedom of creation, participation of society, stimulus of artistic creation, and the decentralization of cultural support. Nevertheless, a large number of these objectives are still in the process of being achieved (Nivón, 2004). It is important to note that Conaculta lacks a clear, articulated policy related to cultural industries. In fact, it was not until the Calderón administration in 2006 that the council included cultural industries in their guideline documents, albeit disjointedly and without any integrative policy or government body to deal with them (Gómez, 2012).

Finally, to compare the Mexican case with the U.S. and Canadian cases of film policies, we will refer to one aspect of Mexican cinematic policy. Through the Mexican Film Institute (Imcine),10 Conaculta aims to promote and finance cinematographic production projects as it recognizes the importance of film for cultural identity as well as because it values film as an art form. Imcine’s annual budget in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2014 was about US$35million, US$33million, US$31million, and US$28.7million, respectively (Mex$436 million, Mex$372million, Mex$357million, and Mex$374.5million) (Imcine, 2010, 2012; dof, 2013). This was distributed through different programs such as those to support film production and promote creators, with a small amount going to film distribution. The agency’s budget to counterbalance the Hollywood distribution industry, which controls 85 percent of the national market, is limited. This trend has continued since the second half of the 1990s (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004; Huerta-Wong and Gómez, 2013).

Audiovisual Industrial Indicators in North AmericaIn this section, we compare industrial indicators of the audiovisual industries for each of the three North American countries in order to establish links between them and their cultural policies discussed above. The data presented by the North American Industrial Classification System (naics) allows us to compare the three North American audiovisual industries. The naics has the objective of harmonizing economic statistical information for nafta members. This information is structured in five aggregate levels of activity, from the most general to the most specific: sector (two digits), sub-sector (three digits), branch (four digits), sub-branch (five digits), and class (six digits). The naics traditionally groups economic activities into three large sets: primary activities (exploitation of natural resources), secondary activities (goods manufacture), and tertiary activities (distribution of goods and services).

Audiovisual products are grouped under the title “Information in mass media,” which mainly includes the industries that create and disseminate products subject to copyright. The group is considered part of the tertiary level of activities, located under distribution services (inegi, 2002: 22). We examined the following subsectors: 512 Film and Video Industry; 515 Radio and Television, except Internet; and 517 Other Telecommunications (referring only to satellite television and cable). naics is a useful instrument for making comparisons both domestically and among the nafta members, allowing us to observe the economic performance of the cultural industries over time.

Nevertheless, the three different agencies that collect the statistical census information have not harmonized all their economic and industrial reports. Therefore, the information we present is not wholly comparable. However, it gives us a feasible picture of the asymmetries and performance of the three national industries.

We also draw on data collected by “Global Entertainment and Media Outlook (ge&mo)” (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2004; 2012) to complement the analysis from 2007 to 2012, since other official data has not been released since 2002.

We compared the gross growth of each sub-sector over time to examine the performance of audiovisual industries in the three countries. We also compared the three cases with regard to the particular growth of strategic categories of cultural production. We analyzed the growth of these audiovisual sectors and compared them to media ownership metrics and market concentration, since we consider these variables as indicators of the negative effects on promotion and conservation of cultural diversity and national identities (Freedman, 2014). Later on, we evaluate the performance of Mexico’s audiovisual industries and indicate their strengths and weaknesses.

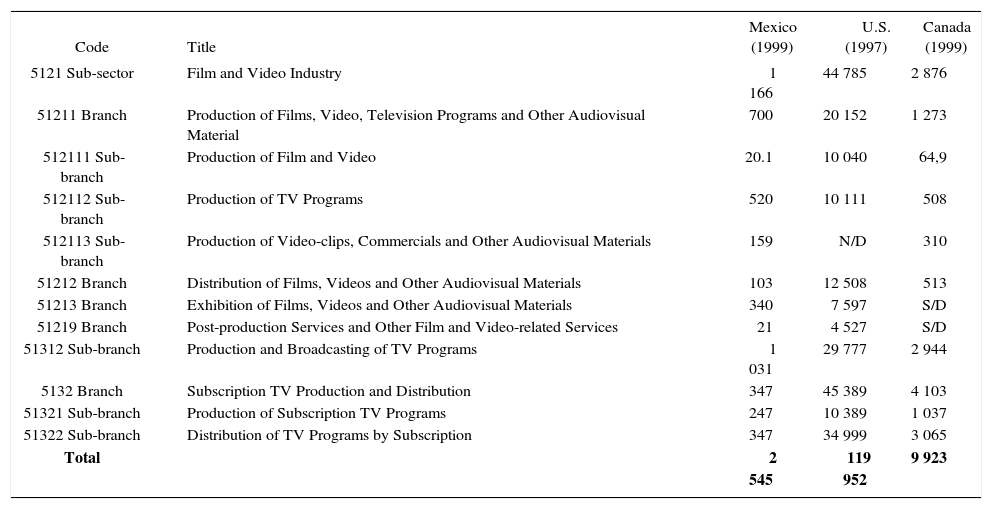

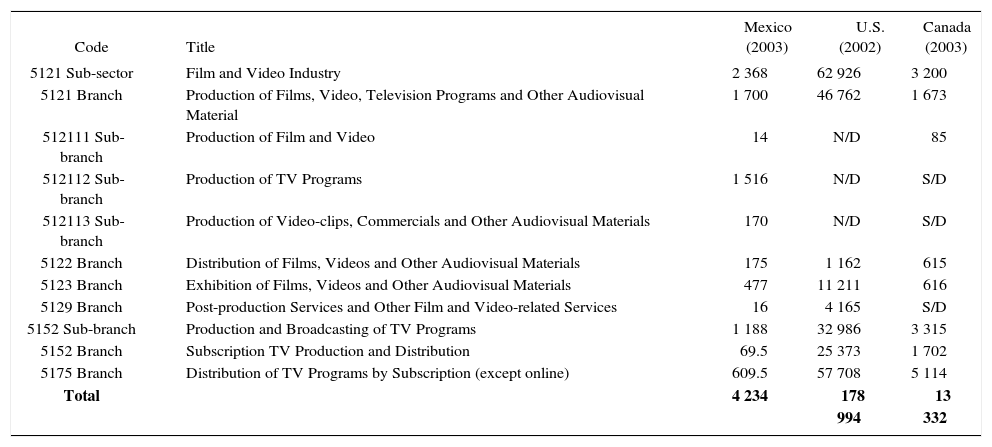

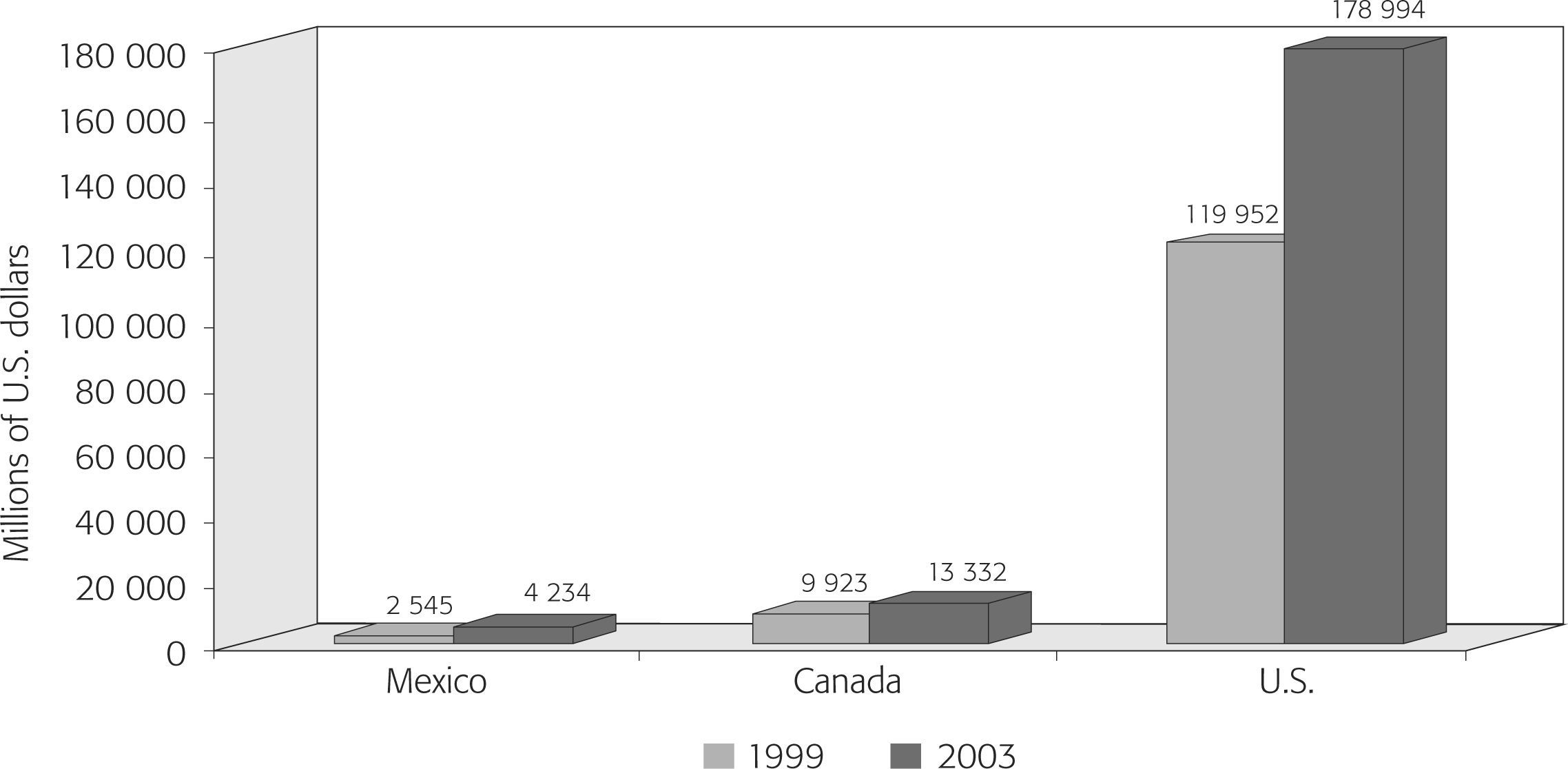

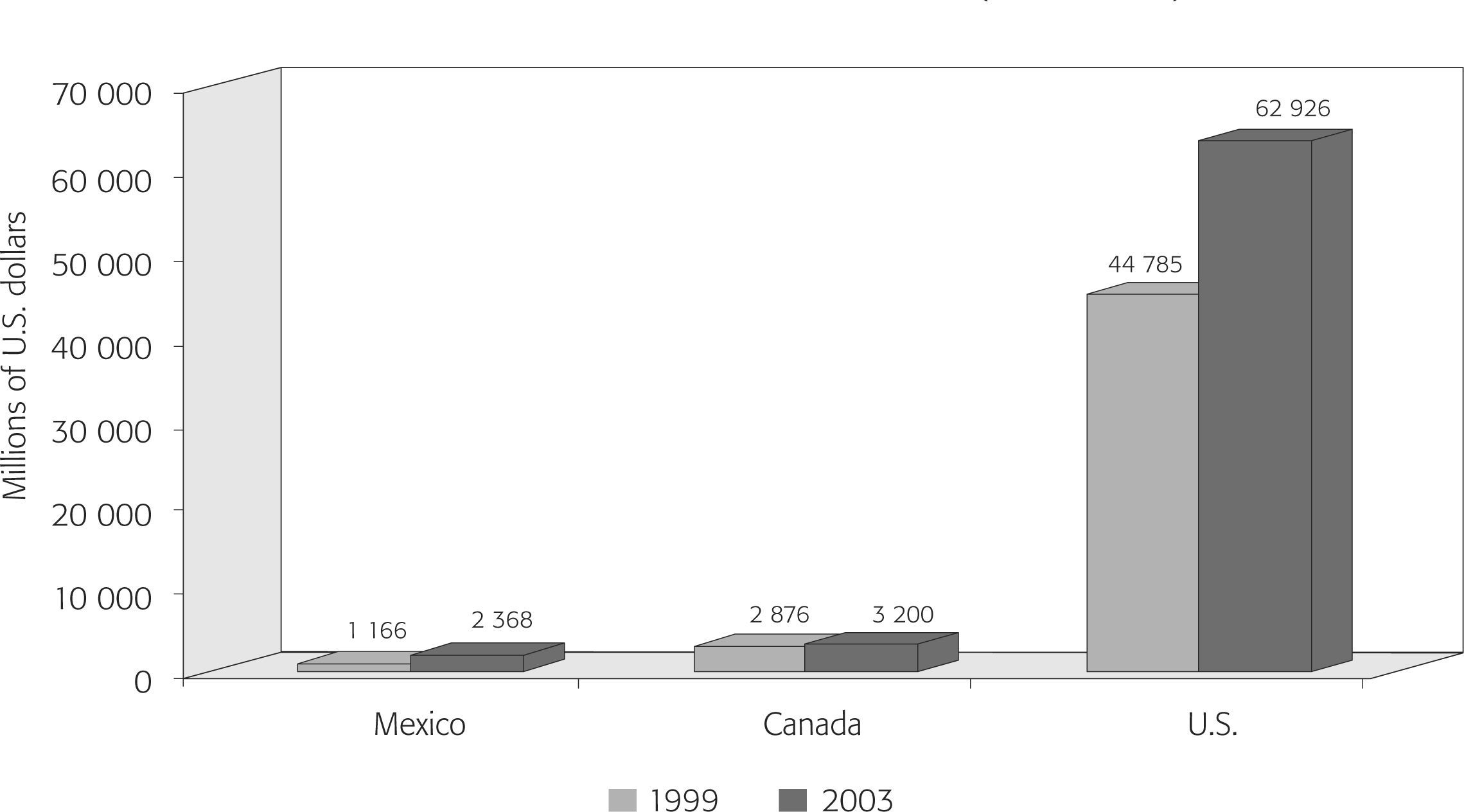

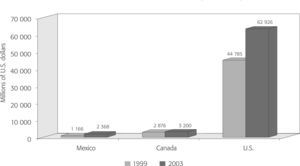

From 1997-2003 and 2007-2012, the three audiovisual industries showed considerable growth in the three countries. The Mexican audiovisual industries grew almost 100 percent from 1999 to 2003, whereas those of the U.S. and Canada (1997 and 2002) grew almost 50 percent (see Tables 1 and 2). This data helps us to understand the significance of audiovisual industries within the whole cultural industries.

Total Income (Millions of U.S. Dollars) of the Audiovisual Industries in Mexico, the United States, and Canada (1999)

| Code | Title | Mexico (1999) | U.S. (1997) | Canada (1999) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5121 Sub-sector | Film and Video Industry | 1 166 | 44 785 | 2 876 |

| 51211 Branch | Production of Films, Video, Television Programs and Other Audiovisual Material | 700 | 20 152 | 1 273 |

| 512111 Sub-branch | Production of Film and Video | 20.1 | 10 040 | 64,9 |

| 512112 Sub-branch | Production of TV Programs | 520 | 10 111 | 508 |

| 512113 Sub-branch | Production of Video-clips, Commercials and Other Audiovisual Materials | 159 | N/D | 310 |

| 51212 Branch | Distribution of Films, Videos and Other Audiovisual Materials | 103 | 12 508 | 513 |

| 51213 Branch | Exhibition of Films, Videos and Other Audiovisual Materials | 340 | 7 597 | S/D |

| 51219 Branch | Post-production Services and Other Film and Video-related Services | 21 | 4 527 | S/D |

| 51312 Sub-branch | Production and Broadcasting of TV Programs | 1 031 | 29 777 | 2 944 |

| 5132 Branch | Subscription TV Production and Distribution | 347 | 45 389 | 4 103 |

| 51321 Sub-branch | Production of Subscription TV Programs | 247 | 10 389 | 1 037 |

| 51322 Sub-branch | Distribution of TV Programs by Subscription | 347 | 34 999 | 3 065 |

| Total | 2 545 | 119 952 | 9 923 |

Total Income (Millions of U.S. Dollars) for the Audiovisual Industries in Mexico, the United States, and Canada (2003)

| Code | Title | Mexico (2003) | U.S. (2002) | Canada (2003) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5121 Sub-sector | Film and Video Industry | 2 368 | 62 926 | 3 200 |

| 5121 Branch | Production of Films, Video, Television Programs and Other Audiovisual Material | 1 700 | 46 762 | 1 673 |

| 512111 Sub-branch | Production of Film and Video | 14 | N/D | 85 |

| 512112 Sub-branch | Production of TV Programs | 1 516 | N/D | S/D |

| 512113 Sub-branch | Production of Video-clips, Commercials and Other Audiovisual Materials | 170 | N/D | S/D |

| 5122 Branch | Distribution of Films, Videos and Other Audiovisual Materials | 175 | 1 162 | 615 |

| 5123 Branch | Exhibition of Films, Videos and Other Audiovisual Materials | 477 | 11 211 | 616 |

| 5129 Branch | Post-production Services and Other Film and Video-related Services | 16 | 4 165 | S/D |

| 5152 Sub-branch | Production and Broadcasting of TV Programs | 1 188 | 32 986 | 3 315 |

| 5152 Branch | Subscription TV Production and Distribution | 69.5 | 25 373 | 1 702 |

| 5175 Branch | Distribution of TV Programs by Subscription (except online) | 609.5 | 57 708 | 5 114 |

| Total | 4 234 | 178 994 | 13 332 |

For example, “Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2001-2004”11 reported that in 2003, U.S. cultural industries generated US$511billion, of which the audiovisual industries, according to our selection of the naics data, accounted for US$179billion (in 2002), representing about 35 percent of the total (pwc, 2004). The percentages do not vary much in the case of Canada: ge&mo reports a total of US$35billion in earnings from cultural industries, with the audiovisual industries accounting for US$13billion, or 42 percent of the total (PWC, 2004).

It is illustrative to compare the Mexican case with the rest of Latin America. ge&mo reports that the Latin American region accumulated US$36billion from cultural industries, which means that Mexican audiovisual industries, generating about US$4.2billion, represent about 15 percent of the entire region.

At the same time, if we compare the US$4.2billion gross revenue generated by the Mexican audiovisual sector with the net income of the two largest leading audiovisual companies in the country (and in Latin America), we gain insight into the market concentration in the audiovisual sector. For example, in 2003, the TV production company Televisa generated US$2.2billion from its audiovisual divisions (equivalent to 85 percent of the group’s net income), while the audiovisual revenue of the other production company, TV Azteca, generated US$638million (90 percent of the group’s net income). Therefore, the two companies’ income accounted for 67 percent (US$2.822billion) of the revenue from audiovisual industries in Mexico in 2003.12

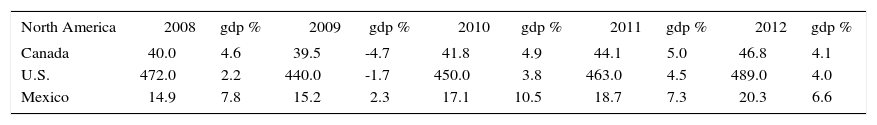

The data summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 confirm the existence of large inequalities among the three countries. For example, in the analysis of the Film and Video Industry sub-sector for the 1999-2003 period (see Table 2), we observed that in Mexico it grew dramatically, by 100 percent (US$1.20billion). Although the U.S. film and video industry grew only 40.5 percent, this made for a significant rise of US$18.14billion. Similarly, the Canadian sub-sector grew 46.6 percent at a pace very much like that of the U.S. and that of the revenue reported in Mexico (US$1.32billion). That tendency was reinforced from 2007 to 2012 (see Table 3).

Entertainment and Media Market by Country (Millions of U.S. Dollars) and Nominal GDP Growth by Country in Entertainment and Media Spending (2008-2012)

| North America | 2008 | gdp % | 2009 | gdp % | 2010 | gdp % | 2011 | gdp % | 2012 | gdp % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 40.0 | 4.6 | 39.5 | -4.7 | 41.8 | 4.9 | 44.1 | 5.0 | 46.8 | 4.1 |

| U.S. | 472.0 | 2.2 | 440.0 | -1.7 | 450.0 | 3.8 | 463.0 | 4.5 | 489.0 | 4.0 |

| Mexico | 14.9 | 7.8 | 15.2 | 2.3 | 17.1 | 10.5 | 18.7 | 7.3 | 20.3 | 6.6 |

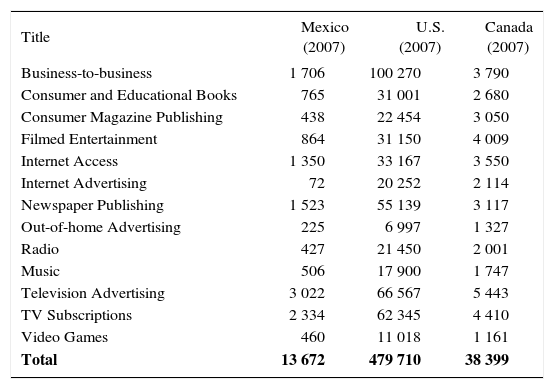

NAFTA Members’ Entertainment and Media Market (2007) (Millions of U.S. Dollars)

| Title | Mexico (2007) | U.S. (2007) | Canada (2007) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business-to-business | 1 706 | 100 270 | 3 790 |

| Consumer and Educational Books | 765 | 31 001 | 2 680 |

| Consumer Magazine Publishing | 438 | 22 454 | 3 050 |

| Filmed Entertainment | 864 | 31 150 | 4 009 |

| Internet Access | 1 350 | 33 167 | 3 550 |

| Internet Advertising | 72 | 20 252 | 2 114 |

| Newspaper Publishing | 1 523 | 55 139 | 3 117 |

| Out-of-home Advertising | 225 | 6 997 | 1 327 |

| Radio | 427 | 21 450 | 2 001 |

| Music | 506 | 17 900 | 1 747 |

| Television Advertising | 3 022 | 66 567 | 5 443 |

| TV Subscriptions | 2 334 | 62 345 | 4 410 |

| Video Games | 460 | 11 018 | 1 161 |

| Total | 13 672 | 479 710 | 38 399 |

Moreover, in the Mexican case, it is important to examine the key sectors and sub-sectors related to audiovisual production. Clearly, the growth is neither even nor stable among the different sub-sectors. Furthermore, we found major weaknesses and drawbacks. For example, the branch of Film Videos, Television Programs and Other Audiovisual Materials Production experienced a growth of almost US$1billion. It could be inferred that audiovisual production in Mexico is rising, which is only partially true. Disaggregating the information by sub-branch performance shows how television program production is largely driving growth in the whole sector. As mentioned above, this is mainly owing to the role of the television duopoly Televisa and TV Azteca, whereas the Film and Video Production sub-branch decreased by about 22 percent. This meant a loss of US$6million for the sub-sector. We determined, therefore, that the film and video production sub-branch is the Achilles heel of Mexico’s audiovisual industry. In contrast, the sub-sectors of film screening and distribution showed constant growth of 40 percent and 68 percent, respectively (see Tables 1 and 2). This upward trend for film exhibition and distribution revenue continued to increase in the following years (see Tables 4 and 5).

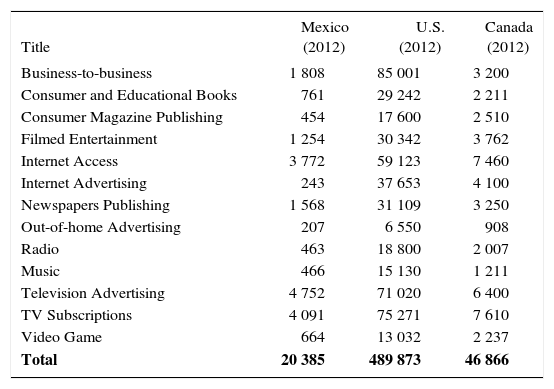

NAFTA Members’ Entertainment and Media Market (2012) (Millions of U.S. Dollars)

| Title | Mexico (2012) | U.S. (2012) | Canada (2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business-to-business | 1 808 | 85 001 | 3 200 |

| Consumer and Educational Books | 761 | 29 242 | 2 211 |

| Consumer Magazine Publishing | 454 | 17 600 | 2 510 |

| Filmed Entertainment | 1 254 | 30 342 | 3 762 |

| Internet Access | 3 772 | 59 123 | 7 460 |

| Internet Advertising | 243 | 37 653 | 4 100 |

| Newspapers Publishing | 1 568 | 31 109 | 3 250 |

| Out-of-home Advertising | 207 | 6 550 | 908 |

| Radio | 463 | 18 800 | 2 007 |

| Music | 466 | 15 130 | 1 211 |

| Television Advertising | 4 752 | 71 020 | 6 400 |

| TV Subscriptions | 4 091 | 75 271 | 7 610 |

| Video Game | 664 | 13 032 | 2 237 |

| Total | 20 385 | 489 873 | 46 866 |

The analysis of the Mexican case using the naics also showed the spectacular growth of the Production of Programs for Channels Distributed by Cable or Satellite Television Systems sub-branch. In 1999, production under this line item reported only US$247 000, reflecting the lack of participation of national production in pay television systems. This amount rose to US$69million in 2003 and has continued to grow ever since. The increase is the result of new regulations for paid television, conditioning satellite broadcaster licensees to invest a small percentage in national programming in order to be able to broadcast advertising (Gómez, 2008). In addition, in recent years the sub-branch of Distribution for Subscription of Television Programs became more profitable than TV advertising (Table 5).

In general, we argue that the audiovisual sector and the film and video sub-sectors show continuous growth for the three nafta members. However, that performance is not necessarily an outcome of nafta. Certainly, the U.S. industries have increased their exports to the Mexican and Canadian markets, but U.S. exports’ rise in North America is only a small part of the global and total U.S. income as the world’s largest exporter. Likewise, Mexican industries’ exports to the U.S. represented a significant percentage of the total (about 10 percent). The driving force for Mexican audiovisual industries is the demographic boom of Hispanic-origin population (mainly Mexican) that is receptive to audiovisual products from Mexico. This places audiovisual industries in a privileged position, as one that provides products for a profitable market in full expansion (Gómez, Miller, and Dorcé, 2014).

Nevertheless, the figures confirmed previous research findings about how nafta has reinforced and broadened the hegemony of U.S. industries over those of its trading partners (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004; Muñoz Larroa, 2009; Tinic, 2010). Moreover, for Mexico and Canada, nafta has meant the consolidation of the historical conditions in which their private audiovisual companies have operated; that is, with indiscriminate access to the purchase of content and signals from the U.S., since screening quotas are minimal in both countries, as well as the maintenance of transnational companies’ control over the largest shares of film distribution and exhibition.

Finally, we present ge&mo data from 2007 to 2012 to complete the overview of the cultural industries after 20 years of nafta’s influence. It is important to underline that the new data from naics 2012 was not available at the time of writing this article. Therefore, we drew on ge&mo 2012-2016 (pwc, 2012).

As Table 3 shows, the growth of these industries is constant and higher than that of the rest of industry (Hesmondhalgh, 2013). This growth can be explained mainly by the changes due to the digitalization of the cultural industries’ production, distribution, and consumption sectors. We argue that this change has expanded the value chain of cultural consumption of audiovisual services in multi-platforms. Examining the data presented by ge&mo, it is important to clarify that they are including internet access business-to-business (b2b) markets.13 Such variables were not included in their 2004 report. However, if we focus on audiovisual markets, the tendency remains upward. For example, in TV Advertising, TV Subscriptions, and Filmed Entertainment the growth is constant, but not as spectacular as the levels of for internet access (Table 4).

In the case of Mexico, we observe that concentration is still a major issue, because Televisa is involved in the two TV sub-sectors, controlling 70 percent of television advertising and around 55 percent of pay TV subscriptions; on the other hand, Telmex controls around 70 percent of internet access, both wired and mobile (Huerta-Wong and Gómez, 2013).

In the case of Canada and the U.S., concentration levels are not as high as in Mexico; however, all their cultural industries’ sub-sectors are increasingly concentrated (Noam, 2009; Winseck, 2011).

Final RemarksThe research suggests that the figures generated by the naics and ge&mo regarding the audiovisual industries for the three countries can be related to different logics of managing and coordinating free-trade-led cultural policy-making in the area of cultural industries. In addition, the sector has clearly experienced continuous economic growth in North America. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight how uneven that growth is among nafta signatories and within each country’s sub-sectors and companies. It is also important to question to what extent the growth translates into economic development and reflects open access to cultural production in terms of cultural diversity and the promotion of creative work.

In the U.S., economic growth is clearly distributed among its global communication conglomerates, especially the big five (Disney, Viacom, Comcast, Time Warner, and News Corp) and, to a lesser extent, among small and medium-sized companies located, mainly, in California (Scott, 2004). We observed that exports of cultural products from the U.S. to its nafta partners have increased and the nafta framework has benefited the circulation of U.S. cultural goods and services (Sánchez Ruiz, 2004; Gómez, 2007; Tinic, 2010). Nevertheless, the growth of Hollywood’s international earnings is due to global trade in the framework of the wto. From 2003 to 2007, the Motion Picture Association of America reported that the earnings from global ticket sales exceeded 53 percent of its total earnings, and in 2007, it had even reached the record amount of 64 percent (US$17.1billion) (mpaa, 2008: 3). The last figure increased spectacularly in 2010 to US$31.8billion due to its growth in the Asia-Pacific region (mpaa, 2010: 1).

On a different note, the Canadian strategy of hybrid cultural policy has also had some favorable results. Its audiovisual industries have grown 50 percent generally over the period studied. The cultural exception mainly benefited the province of Quebec, allowing it to continue subsidizing its cultural industries via its Ministry of Culture and the Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (Sodec) and to protect and promote domestic television production using screening quotas (Lozano, 2006).

On the other hand, the British approach to cultural policy found in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia has tended to assist the private sector. However, most of the investment in Ontario’s cultural industries is driven by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation with its headquarters in Toronto. In addition, British Columbia has become one of the favorite places outside Hollywood for filming both television series and feature films (Tinic, 2008; Newman, 2008). The British Columbia government has invested millions of dollars in infrastructure to guarantee the modernization of studios in order to avoid losing the economic opportunity resulting from the audiovisual production of U.S. series and films.

Finally, in the case of Mexico, we noted a high concentration of its audiovisual industries involved in producing and broadcasting television programs. This creates a contradictory situation. While the economic results show a significant growth of almost 100 percent over the period, sources of employment were reduced and the growth of audiovisual companies stagnated (Gómez, 2008). By contrast, Televisa and TV Azteca are the only two large companies that have increased their total revenue continually over those years. Furthermore, Televisa operates in all the audiovisual sub-sectors and branches, and has even carved out a dominant position in the sector of pay television. At the same time, due to the multiscreen and mobile convergence scenario, Telmex is another large company that has benefited from the new forms of cultural consumption by concentrating the markets for internet access.

Although there is economic growth in Mexico, the reason it does not translate into economic development is that only some sub-sectors and branches are growing. Furthermore, growth is exclusive to dominant audiovisual and telecommunications companies, which benefit from the lack of competition. In other words, growth is confined largely to communication conglomerates that focus on television production, cable and dth broadcasting, internet access, cinema exhibition, and a handful of Hollywood-based film distribution companies.

The market concentration by the dominant players creates economic barriers, a blocking effect for new business enterprises, particularly with independent producers. At the same time, nafta allows large companies to sustain constant growth and a privileged position in international competition. In Mexico this could change in the future, after the Federal Telecommunications Institute (ift) revaluates Televisa’s and Telmex’s market shares. However, in the 20 years of nafta the increased concentration of the audiovisual sector in Mexico has become evident.

Mexico’s cultural policies do not encompass the cultural industries. In fact, this is a major challenge for the future of cultural policies. Their absence in the official discourse frames Mexican cultural industries as de facto being under the laissez-faire and free-market logic. This, in turn, is in line with nafta’s treating cultural products like any other piece of merchandise, and also threatens the rest of the cultural sectors in terms of the possibilities for government intervention.

This analysis provides inputs for establishing the links between the asymmetries shown by industrial economic data and the Canadian and Mexican cultural policy traditions, reshaped under the free-market dynamics of the nafta framework. In this regard, we have attempted to contribute to understanding the different contexts of global capitalism in which cultural industries and their policies are embedded.

This research was funded by the Faculty Research Program of the Canadian Government in 2008, Fulbright-García Robles Research Grant from 2013-2014, and Conacyt Estancias Sabáticas 2013-2014.

The gdp of the three countries in 2012 was the following: Canada, US$1.82billion; Mexico, US$1.18billion; and the U.S., US$15.47billion (World Economic Outlook Database, 2013).

British, U.S., and Australian capitalism is characterised as being “individualistic and predatory.… The North American model, in full decline, is highly dynamic but anti-social, short-term led, anti-investing, and exacerbates inequalities” (Castañeda and Heredia, 1993: 20).

In 1991, the Motion Picture Association of America (mpaa) reported its export earnings at US$7billion (cited in McAnany and Wilkinson, 1995: 8); from films shown and distributed throughout the world alone, it earned US$4.8billion (mpaa, 2003: 4). In contrast, that year the Canadian industry reported US$28million from exports, and in the Mexican case, Televisa reported US$20million (cited in McAnany and Wilkinson, 1995: 8).

This situation has been called “Americanization.” Carlos Monsiváis (1992) notes it as generalized among middle-class Mexican youth, who think of it as a guarantee for achieving an international mind-set.

This position understands the state as a partner in the task of promoting culture, that is, a facilitator for demands of foundations and civil society, conceiving the cultural environment as a matter related to the private sector. The position also promotes the idea of non-interference.

The French tradition on the role of the state in cultural policy is based on the assumption that the state has the right to use its power to promote the blossoming of culture on behalf of its citizens and to promote the development of a strong national identity.

The main national institutions are the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (cbc), the National Film Board and Telefilm Canada, among others. The agency that regulates and oversees the mass media and telecommunications in Canada is the Canadian Radio Television and Telecommunications Commission (crtc).

We should highlight that, since television was developed in the U.S. and Canada, there was always significant penetration of U.S. audiovisual products in Canada. Nevertheless, the basic problem was that with the re-regulation and opening up to the U.S. media companies, Canadian infrastructure could not maintain the counterbalances via domestic audiovisual production. That is, from both the cultural and the economic point of view, head-to-head competition with its neighbor’s industry could mean the loss of jobs and direct investment in Canadian companies.

The numbers are illustrative. For example, between 1996 and 1997, among 200 television series and films produced, only 20 percent were Canadian productions and the rest were from the U.S. (Rice-Baker, 1997: 3). For the year 2000, the economic earnings from the audiovisual industry in British Columbia surpassed US$1.18billion (Tinic, 2008: 252). The 2006-2007 Report from British Columbia Film informs that in that period, the figure was US$1.2billion (2007: 6).

The objectives of the Institute are a) to consolidate and increase national cinematographic production; b) to extend the promotion, dissemination, and distribution of Mexican films; and c) to establish an industrial promotional policy in the audiovisual sector.

It is important to clarify that this report’s methodology has changed over the years. Before 2003, its outlook included more entertainment industries such as professional sports, concerts, and theme parks, among others. But since 2005, it changed its categories as shown in Tables 4 and 5.

For greater insight into the Mexican case, see Gómez (2008).

The business-to-business market (b2b) is divided into five segments: business information, trade shows, trade directories, trade magazines, and professional books.