Recently, harsh immigration policies have made the lives of the new immigrant Diaspora in the southeastern United States extremely challenging. Disturbed by the impact of these sociopolitical changes on students, their families, and their teachers, as multicultural educators, we have turned for help to recent research and praxis from the U.S. and Europe that overtly challenges anti-immigration discourse. We examine two theoretical perspectives that can support educators in talking back and acting against anti-immigration discourses and practices in schools and communities. We provide cases of our own work in the southeastern United States to test the value of these theories.

Recientemente, las políticas migratorias punitivas han hecho muy difícil la vida de la nueva diáspora de inmigrantes en el sureste de Estados Unidos. Preocupadas por el impacto de estos cambios sociopolíticos en los estudiantes, sus familias, sus maestros, como educadoras multiculturales hemos buscado apoyarnos en las prácticas e investigaciones recientes en Estados Unidos y Europa que desafian abiertamente los discursos antiinmigrantes. Examinamos dos perspectivas teóricas que pueden ayudar a los docentes a responder y actuar en contra de los discursos y prácticas antiimigrantes en las escuelas y las comunidades. Utilizamos casos de nuestro propio trabajo en el sureste de los Estados Unidos para probar el valor de estas teorías.

Francisco was on his way to work when he got into a minor traffic accident. Instead of being released to the care of his family, he was detained and taken to Irwin County Detention Center. Francisco has lived in the U.S. for 15 years now; he has 4 children who need him, and has no criminal history. Why is he imprisoned? take action-make a call (Dream Activist, 2013)

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, anti-immigrant discourses and harsh immigration policies have posed tremendous challenges to immigrant students, their families, their teachers, and their communities. Calls to action to protest anti-immigration violence and police actions, as articulated in the e-mail quoted above, have appeared with increasing regularity. Beginning in the mid-1990s, and with another surge in the mid-2000s, the xenophobia that was embedded in policy and daily life in the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries (Pfaelzer, 2008; Takaki, 1989) has resurged throughout the United States. Strident voices in the national media, as well as citizen and state legislative initiatives, express open hostility toward immigrants in the United States, seemingly without any fear of social sanction (De la Torre, 2011; Pulido, 2007; Santa Ana, 1999). Aggressive enforcement of U.S. federal laws related to the employment of undocumented workers has also led to an increasing number of public, dramatic, and frightening detentions and deportations of immigrants (Argueta, 2011). These recent trends in anti-immigrant public discourse and law enforcement in the United States reflect parallel developments in European countries such as France, Great Britain, Greece, Spain, and Italy (Chrisafis, 2010; Duffy, 2012; Trilling, 2013) and other nations with expanding immigrant populations such as Israel (Greenwood, 2012), Canada (Freisen, 2012), and Australia (Wright and Masanauskas, 2012).

Fortunately, at the same time, initiatives at the regional and national levels in some countries are advocating for positive legislation and government regulations that would validate and integrate undocumented immigrants into society. The proposed federal “Dream Act” in the United States, for example, would facilitate access to higher education for undocumented students who have completed their primary and secondary education in the United States (National Immigration Law Center, 2011). In 2012, the U.S. government also implemented a new policy (referred to as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) that offers the possibility of work permits to undocumented students (United We Dream Network, 2012). In France, in the wake of the 2005 anti-immigrant riots in Paris suburbs, citizens set up community advocacy groups to support equal rights for young people with undocumented immigrant parents (Chrisafis, 2010). In Greece, a national network named Solidarity4All has coordinated initiatives to support immigrant and native-born Greek populations in coping with unemployment and falling salaries. The initiatives include discount prices on farm food and also free medical clinics and after-school tutoring for students. In Thailand, the Thai cabinet approved a resolution in 2005 granting migrant children access to a free public education (Arphattananon, 2012). These developments in a wide range of contexts demonstrate that the educational, economic, and legal terrains for immigrants, and especially for undocumented immigrants, are shifting and treacherous, but also that new possibilities are opening up in some global locales. What is also evident is that the challenges, hopes, and activism of immigrant student populations, sparked by socio-political developments in countries around the world, have permeated the collective imaginations of students, parents, teachers, and university educators working in a wide range of educational contexts (Crozier, 2009; López and Minushkin, 2008; Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco, and Sattin-Bajaj, 2010; Thorpe, 2009).

As educators immersed in our ongoing collaborative work with immigrant students and as recent co-editors of a journal special issue on immigration discourses and practices (ijme [International Journal of Multicultural Education], 2012), the purpose of our article is to outline the critical socio-cultural perspectives that have helped us grapple with the complex interplay of immigration and education policies and practices. We highlight the eight research studies from our ijme special issue as exemplars of the praxis developing on a global level where critical and poststructuralist theories are embodied in collaborative, arts-based, and resource-based approaches that validate the lived experiences of immigrant students. At the same time, they challenge the socio-cultural conditions that minoritize this population (see Chapell and Faltis, 2013) in different regions of the United States and in Italy.

Our article is divided into two main sections. The first section on critical discourse analysis (cda) explores how this theoretical and methodological framework can help educators and researchers re-conceptualize the representation of immigrants in policy and classroom contexts. We provide a case study from our work in the southeastern United States that builds on and tests the value of this approach. The second section explores how critical race theory (crt), and corresponding resource pedagogies, support inquiry into race, identity, and power issues at state and local levels, using community voices and participatory approaches to shift classroom and social discourses away from deficit perspectives on race and identity. We provide a second case study from our work to illustrate the ways in which resource pedagogies play out in an educational project engaging a group of Latino immigrant students, their parents, and their teachers in the southeastern United States.

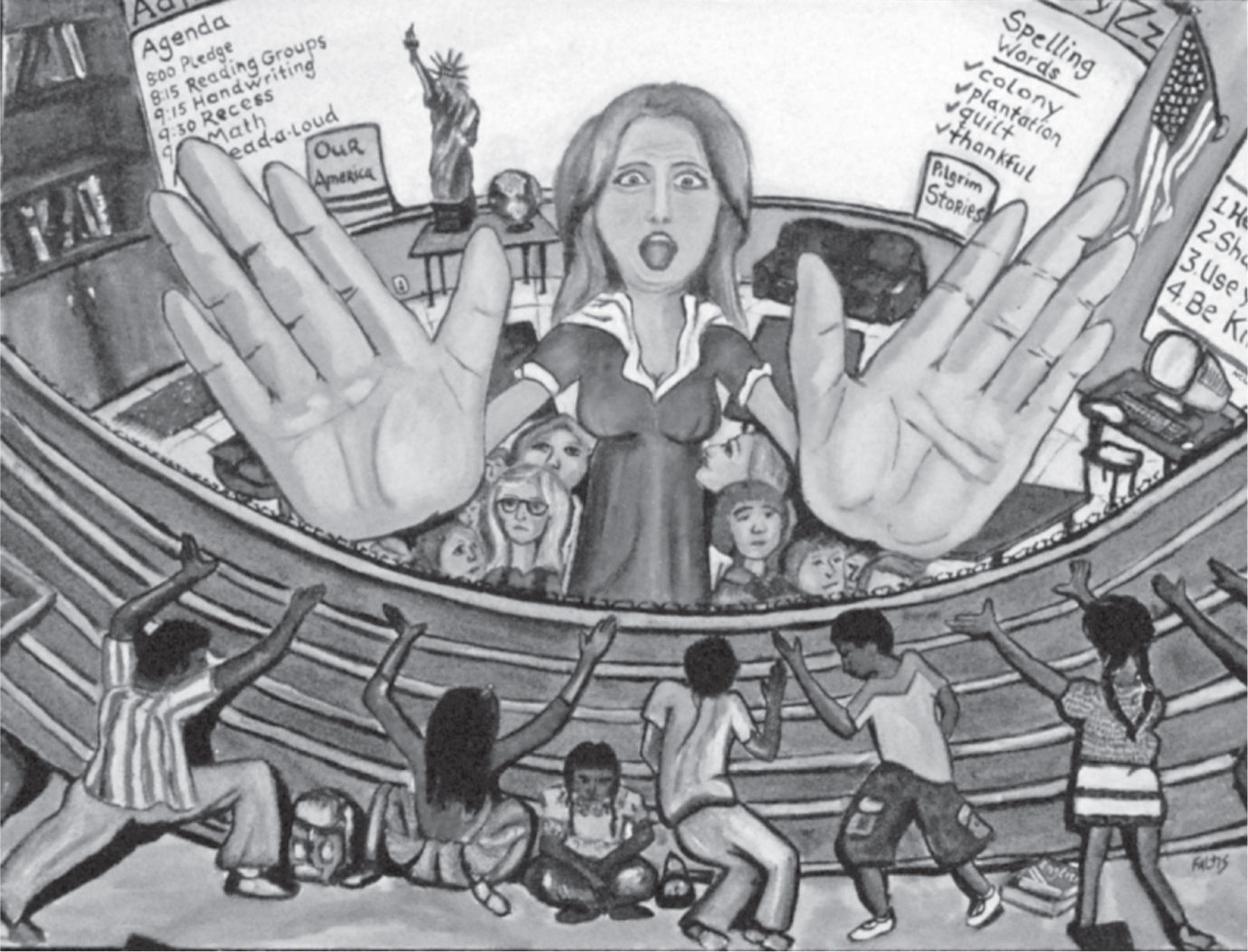

Throughout the article, we have used the artwork of Chris Faltis –see Section II for a description of his work– to highlight tensions and conflicts. In sum, we use the work of the other authors in the ijme issue, as well as our own research projects, to answer the question: How can a praxis informed by two mutually supportive theoretical orientations empower researchers to challenge anti-immigration policies, practices, and discourses in our scholarship?

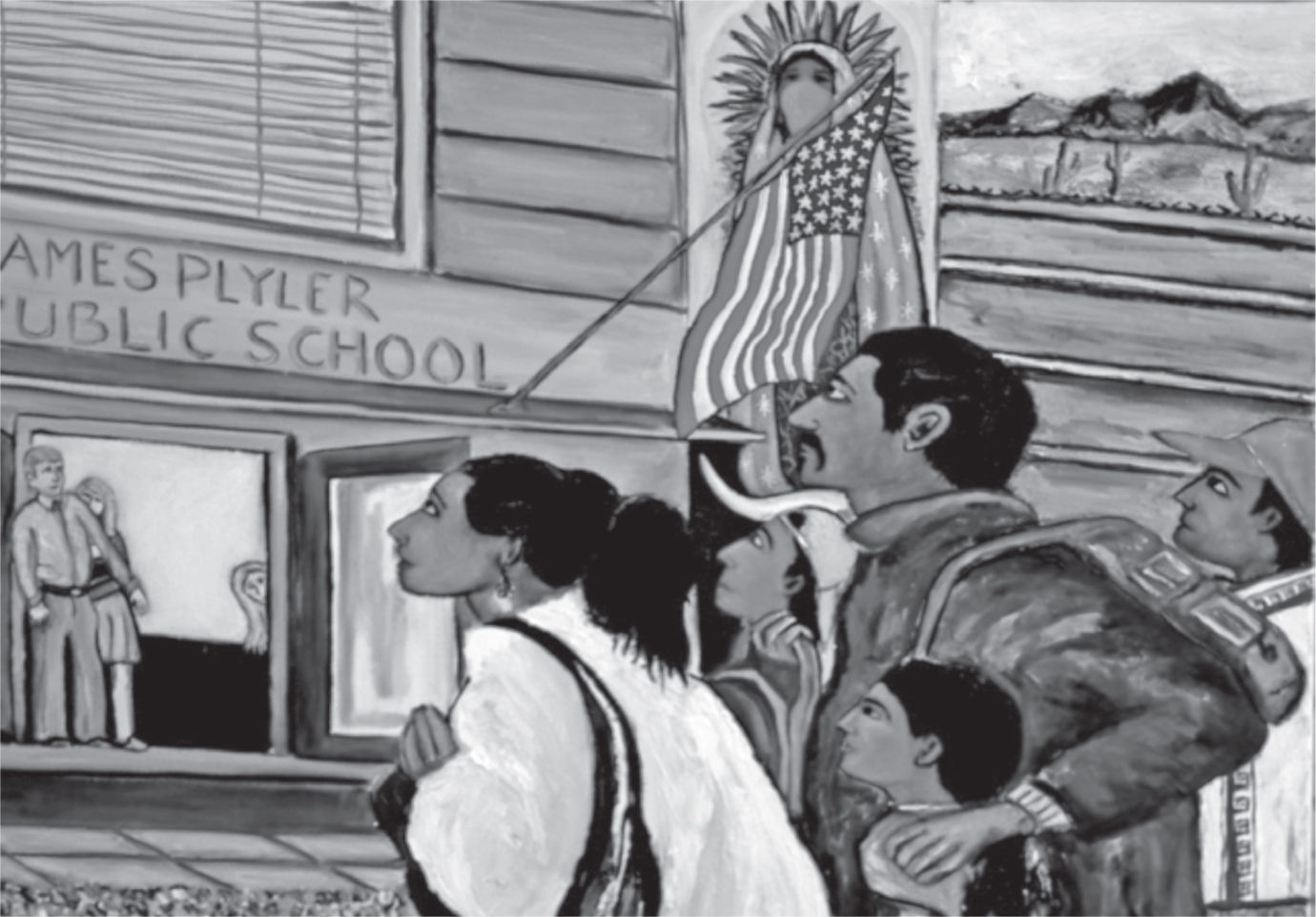

Critical Discourse Analysis as a Tool to Challenge Anti-immigration PoliciesAs illustrated by Chris Faltis (2012: 12) in Figure 1 above, radical right-wing groups in the U.S. frequently attempt to overturn Plyler v. Doe, a Supreme Court decision that provides undocumented students with equal rights to K-12 education. Very recently, state legislators have attempted to make access to schooling more difficult for undocumented students by ensuring that they needed to show their papers when registering for school (for example, in Alabama).1 As Faltis explained about his artistic process in the painting illustrated above, he “imagined the Virgen with a bandana, and placed the border fence in the background to show that any effort to close off schools to children of Mexican immigrants is another type of border” (2012: 12). Faltis's imaginative pairing of visual political art and written research engages viewers in dialectic processing of visual reception and social construction of immigrant identities.

In this way, Faltis's work aligns closely with a critical discourse analysis (cda) approach, which focuses on the analysis of inequitable power structures and transformative social change (for example, Fairclough, 2005). In the section below, we first discuss the main tenets of cda, then briefly discuss two articles from our special issue including Faltis's, and illustrate through the work of Harman and Varga-Dobai (2012) how cda can be used as a pedagogical and analytic lens in working with K-12 emergent bilingual students. Our purpose is to provide readers with a working knowledge of how cda might be applied in critical and transformative ways when challenging current immigration policies and practices.

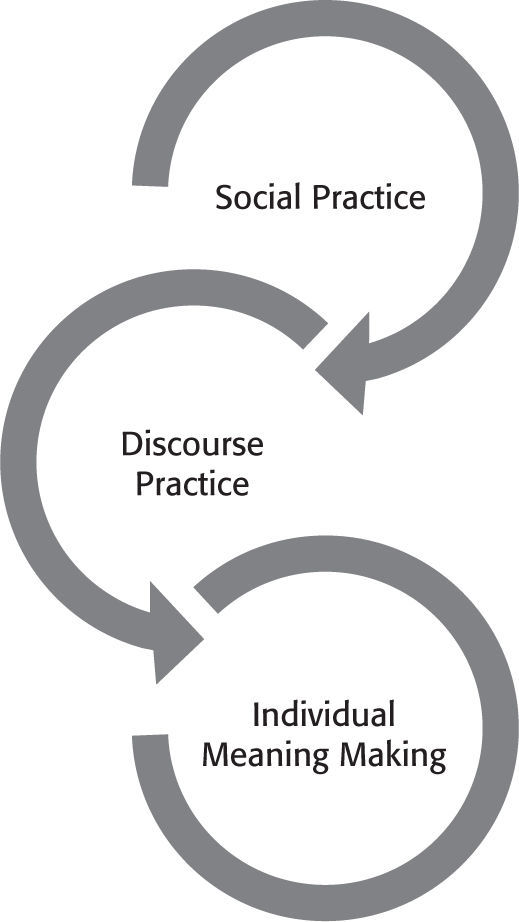

As Fairclough (2005) highlighted in his paper on transdisciplinary research, a multilayered cda approach focuses on the dialectic between individual meaning-making events and the social structures and practices on which they rely. In other words, it explores the dynamic relationship of the social agent to social structures. To explore the interconnections, Fairclough (2005) conceptualized a three-dimensional analytic framework of text, discourse practice, and social practice (See Figure 2 below).

As Figure 2 illustrates, an analysis of the patterns of meaning making at the individual level (for example, student and teacher interactions in a second-language classroom) is connected to an investigation into the institutional and societal practices that validate and/or marginalize the communicative practices of a particular discourse community. Also from this critical perspective, hegemonic control is never fully established since it is always contested by the tactics of “subordinate” social groups. In other words, individuals are not only subjected or colonized by dominant discursive systems; they transform them, even if in very subtle ways.

A cda analysis will often begin by exploring the configurations of language use in an individual or set of texts to see how they conform to particular pervasive ideological perspectives. In analyzing the interpersonal aspects of a political speech, for example, “we see the power of language to construe our experience of the social world and to enact social roles and relations, while at the same time creating a universe of information” (Butt, Lukin and Matthiesen, 2004: 269). In our ijme special issue, several researchers used critical discourse analysis or other closely related approaches to grapple with often-taken-for-granted ways of representing immigrants.

Ryan Gildersleeve and Susana Hernandez (2012), for example, integrated critical discourse analysis and policy analysis in their study titled “Producing (im)Possible Peoples: Policy Discourse Analysis, In-state Resident Tuition, and Undocumented Students in American Higher Education.” They used these analytic methods to explore the human realities enacted by the discourse of the in-state resident tuition policies between 2001 and 2011 in 12 U.S. states (California, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin). Through their multi-dimensional analyses of new discursive identities in policy documents, they showed how students without papers in higher education were afforded social labels not previously available in political, popular, or educational discourse: for example, policy documents discussed the “alien student” and the “student alien.” As the authors highlighted, real living students had to confront, enact, and resist such descriptors in their college classrooms and lives. Gildersleeve and Hernandez challenge educators who see themselves as being on the “right side” of the issue of supporting immigrant students to think pro-actively about new pedagogical discourses that refrain from using and perpetuating binary terms such as “alien student” or, indeed, “undocumented student.”

In a different approach that is not termed critical discourse analysis but still conforms very closely to Fairclough's tri-dimensional analytic approach, Chris Faltis used a dynamic methodology he referred to as double-imaging. In his article entitled “Art and Text as Living Inquiry into Anti-immigration Discourse,” Faltis interwove illustrations of eight of his oil paintings, created in a visceral realist style, that depict borders and border crossings in the southwestern United States, with written texts that characterize immigrants' challenging experiences. Faltis's living inquiry with interwoven works of art and written text dare each of us to face the mix of emotions and commitments entangled in our work and research with immigrant students and their families.

Immigration Discourses in the Southeastern U.S. Region: A Case StudyTo illustrate in detail how a critical discourse approach can embed analytic and critical action research around immigration issues, we discuss why and how Harman and Varga-Dobai, along with a collaborative team of teachers/ researchers (for example, 2012), conducted an arts-based critical performative approach (cpp) with emergent bilingual learners in a high-poverty middle school in the southeastern U.S. Harman had spent two years prior to the cpp action research project as a participant observer and co-teacher in an English-for-speakers-of-other-languages (esol) classroom using a sheltered instruction approach at Chestnut Middle School (pseudonym). Harman and her co-researchers/teachers found the social and immigration policies and practices in the region exerting a direct impact on the emotional and academic well-being of the middle-school emergent bilingual community predominately from México and El Salvador. For example, students expressed great concern about a ban instituted by the Georgia University System Board of Regents in October 2010 designed to prevent undocumented students from gaining admission to selective universities in the state regardless of high achievement records (University System of Georgia, 2010). Symbolically, the ban represented a dismissal and exclusion of undocumented students, preventing them from fulfilling their academic dreams.

In addition, other types of anti-immigration legislation were proposed and passed in the state legislature in the same time period, including 2011's House Bill 87, which re-enforced immigrant status reviews and deportations (Georgia General Assembly, 2011). Understandably, such practices triggered high anxieties for the student participants and their home communities. Some students shared that they lived in constant fear that their parents or other community members would be taken away at night by immigration services and that they and their siblings would be placed in state custody (Harman and Varga-Dobai, 2012). As Stevenson and Beck (2013) underlined, the inequities of the immigration system have had a deleterious impact on immigrant families, especially on the millions of mixed-status households where the children know that a member of their immediate family could be swept up and deported at any time.

Arts-Based Youth Participatory Action ApproachHarman, Varga-Dobai, and teacher/ researchers at Chestnut Middle School decided to take a critical arts-based approach informed by Boal's Theater of the Oppressed (1979) in teaching a social studies class for bilingual learners in 2009–2010. The classroom participants included one Italian/Somalian and eight Latina emergent bilingual learners. The enacted cpp approach was closely aligned with recent qualitative research on Latina/o youth literacy that encourages educators to take a critical participatory approach to literacy instruction (Gutierrez, 2008; Martínez-Roldán and Fránquiz, 2009). In Gutierrez's action research with the Migrant Institute, for example, students/teachers/researchers engaged in teatro, critical theory, and discussion of the socio-political context of schooling, dialogic processes which had the potential of reframing everyday and institutional literacies into “powerful literacies oriented toward critical social thought” (2008: 149).

The sequential stages of the Chestnut Middle School team's work over the course of a year and a half included the sequential use of performance, storytelling, collective voting and writing, as well as conference presentations:

- •

History of names through theater games

- •

Sharing of student and teacher family narratives (for example, about La Llorona)

- •

Explanation of the goal of a critical performative approach

- •

Boal's (1979) theater techniques used to identify community's social issues

- •

Voting and decision on what social action to use to address student-identified social issues (abrupt deportation and job discrimination)

- •

Research, community interviews, immigration lecture, and drafting of informational texts

- •

Publication of a newsletter and public performance for families on Cinco de Mayo

- •

Creation of a bilingual theatrical script and power point for conferences

- •

Presentations at a Women Studies Conference (fall 2010) and at a local university (spring 2011).

The critical arts-based participatory approach, in the context of multicultural and second language education, supported students and teachers in grappling with local power relations that were dialectally connected to broader institutional and societal practices that marginalize students and teachers based on race, class, gender, and other markers of difference (Nieto and Bode, 2008).

CDA Analysis of the ProjectA critical discourse analysis was conducted by the adult researchers to cast a reflexive eye on how their critical arts-based approach facilitated or constrained students from engaging in collective literacy processes and social action. Systemic functional linguistics (sfl) analysis, which helps to investigate how language functions in different social contexts, was used to investigate the linguistic and rhetorical patterns in the oral and written classroom discourse (Eggins, 2004; Halliday and Matthiesen, 2004). Findings from the study pointed to how the critical arts-based approach, although problematic in terms of not involving insider community members, encouraged the students to use a range of genres in their oral and written discourse (for example, storytelling, dramatic replay, discussion, and newsletter composition) to communicate their emotions and research about immigration issues they had identified. The student involvement also supported adult participants in learning about and challenging the local community issues. Indeed, as a result of their work together, some of the adult participants became more involved with Latino families in fighting against issues such as the ban on undocumented students from entering higher ranked universities in Georgia.

When taken together, the three research studies in this section illustrate how educators in the twenty-first century can challenge the effects of immigration policies and practices through critical analysis of macro-level policies and practices; artistic exploration and challenging of discourse practices related to border crossing, bilingual policies, and linguicism; and development of insurgent pedagogical practices that disrupt the deficit discourses about immigrant students. Civil rights organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union and Latino activist groups are also involved in challenging legislation in various states in the U.S. that criminalizes immigrant populations through racial profiling and other nefarious policies (see footnote 1 on Alabama). It is only through consistent use of academic, legal, and collective social action that communities can effect change with and for immigrant families who have been minoritized and silenced. The shutting down and subsequent re-opening of the ethnic studies program in the Tucson school district provides an important exemple of a setting in which educators, citizens, legal groups, and legislators negotiated conflicted terrain that incorporated efforts to both support and suppress immigrant, multilingual, and multicultural voices (Acosta and Mir, 2012). Critical discourse analysis, in sum, provides a robust analytic and social action framework in our collaborative work on these issues.

Critical Race Theory and Resource Pedagogies: Tools to Challenge Anti-Immigration Discourses and Develop New PraxisIntertwined with critical discourse analysis, critical race theory (crt), developed through the work of U.S. legal scholars, has been applied to educational research as well as other fields. It articulates a set of interrelated beliefs about the significance of race and racism as it operates in contemporary educational institutions and policies (Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995; Ladson-Billings, 2005; Tate, 2005). crt scholars such as Derrick Bell (1992) explore the multiple ways that U.S. law, politics, and institutions of power shape the “truth” so that the rights and privileges of a dominant group are guaranteed by the simultaneous silencing and distortion of the rights of those seen as “minorities.” The insidious “techniques of power” used to create the illusion in the U. S. that we have equal justice, access, and speech rights pervade our everyday practices, our speech acts, our homes, and our communities (see Delgado and Stephanic, 2012).

Although crt has mostly been applied to U.S. sociopolitical contexts, Gillborn (2006) suggests that the perspectives embedded in crt also offer effective conceptual tools for educators in other geographic regions that are grappling with legacies of colonialism and school inequalities. Stephanie Love and Manka Varghese (2012), with their article “The Historical and Contemporary Role of Race, Language, and Schooling in Italy's Current Immigrant Policies and Pedagogies,” adapt critical race theory to the Italian socio-political context. Specifically, they explore the socio-historical construction of the Italian nation-state and its current intercultural curriculum policies. By employing key crt tenets that include acknowledging racism as an enduring aberration in society, Love and Varghese expose how structures of power linked to race and language play out in the workings of the historical and contemporary Italian nation-state and its nationalist ideologies.

Their analysis leads them to conclude that the curriculum approach touted in the state educational policy document titled “The Italian Way for Intercultural Schooling and the Integration of Foreign Students” is inadequate for reaching the goal of preparing students from migrant origins to participate in Italian society. They propose, instead, a crt framework adapted to Italy's socio-historical context that addresses global migratory patterns and anti-immigrant discourses as they are played out in Italy today. Love and Varghese see this approach as a more dynamic means for helping both educators and students grapple with the ways that schooling serves to embody and enforce language and racial ideologies in Italy and other countries experiencing immigration in the twenty-first century.

The study conducted by Love and Varghese argues for the value of critical race theory as a catalyst for teachers and students to challenge anti-immigrant discourses and practices at the national and state level, as well as in the classroom. From this crt perspective, a logical response to the minoritizing of immigrant youth is to develop pedagogies that support and value linguistic, cultural, and literacy resources that all students, including immigrants, bring to school. Before discussing the articles in our special issue and our own work that represent key elements of such resource pedagogies, we provide a brief socio-historical overview of how the educational positioning of the cultural and linguistic “other” has evolved over time from deficit to difference to resource in the work of many critical educators across the globe.

Cultural and linguistic deficit models (also called cultural deprivation models) gained favor in the early part of the twentieth century as a way to explain the perceived inferiority of culturally and linguistically “different” individuals (largely immigrants) in schools, the workplace, and other social settings (for example, Darcy, 1963). The pedagogical implications of this perspective were that students from cultural and linguistic minorities were destined for academic inferiority unless their culture and language were replaced by “mainstream” culture and language. Several more modern attempts have been made to revive the argument for racial, cultural, and linguistic superiority and inferiority (for example, Herrnstein and Murray, 1994), yet such attempts have continued to be discredited as both inaccurate and unfair portrayals of cultural differences (Fraser, 1995). Still, while scholarly discourse has largely moved past a deficit view of understanding cultures and languages other than one's own, a cultural and linguistic deficit perspective on immigrants (as well as other students of color) persists and has even strengthened in some of the popular discourse around schooling, academic standards, and educational accountability.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, the deficit perspective was replaced in educational research by models of cultural and linguistic difference that acknowledged the variations between groups and individuals without presuming that one culture or language was inherently superior to another (for example, Fordham and Ogbu, 1986). Cultural difference theories are grounded in the idea that linguistic and behavioral differences arise when groups face divergent historical, social, and economic conditions. Children learn the culture of the group through child-rearing practices that lead, in turn, to consistent patterns of behavior, language use, thinking, and feeling for individuals within groups. Numerous scholars in the later twentieth century used this framework to interpret the educational experiences of students from “non-mainstream” cultural and linguistic groups (for example, Heath, 1983; Tharp and Dalton, 1994), and, indeed, many educators continue to hold this view of culture and language in their classrooms today. The pedagogical implications of the “cultural difference” perspective are that students should be encouraged to preserve their cultural and linguistic heritage while also learning mainstream language and culture, but that these two projects are largely disconnected.

In recent years, many teacher educators have adopted the framework of resource pedagogies to replace the cultural and linguistic difference perspective. The notion of resource pedagogies is often traced to Ladson-Billings's culturally relevant pedagogy (1995), which highlighted the need for teachers to simultaneously address three themes in their classrooms: academic achievement, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. Inherent in this approach is the belief that the linguistic, cultural, and literacy tools that all students bring to the classroom can be used advantageously to develop the knowledge and skills most valued in academic settings. Focusing more explicitly on the needs of English learners (including immigrants), Lee and Fradd's (1998) model of instructional congruence and Gonzalez, Moll, and Amanti's (2005) funds-of-knowledge approach both highlighted the need to develop stronger connections between school-based academic content and literacy skills, and the knowledge and language that students bring from home. In the most recent variation on this perspective, Paris proposed a model of culturally sustaining pedagogy that strives to “ensure maintenance of the languages and cultures of … longstanding and newcomer communities in our classrooms” (2012b: 94), while taking “a critical stance toward and critical action against unequal power relations” (95). For Paris, the goal of culturally sustaining pedagogy is to foster “linguistic, literate and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (95).

In the article entitled “Become History: Learning from Identity Texts and Youth Activism in the Wake of Arizona sb1070,” Paris (2012a) illustrates how a critical standpoint on language, power, and identity can be practiced as well as theorized. In his action research with Latino students in a U.S. high school English class, Paris explores the disjuncture between immigrant students' participation in protests against anti-immigrant state policy in Arizona and their teachers' well-intentioned, but ultimately unsuccessful, attempts to incorporate discussion and study of race and class-based inequities in U.S. society into classroom literacy practices. He draws on a humanizing research stance, committed to developing relationships of dignity and care with his participants, as he shows himself interacting with students in the back of classrooms and hallways of the school and in a student-organized walkout and protest at the state capitol. Paris (2011) argues that our research and praxis in contexts characterized by conflict and inequities must involve “dialogic consciousness raising” with our research participants. In analyzing the seemingly disconnected texts that students actually attended to in the classroom (text messages, corridos, and raps), the texts they were assigned to study (Langston Hughes, William Faulkner, Elaine Hansberry), and the texts they participated in as activists (signs, shirts, and chants), Paris sheds light on the potential for educators to connect the struggles depicted in literature to the continuing struggles in students' lives.

While our school systems today often claim to honor and value diversity, the day-to-day reality of accountability policies, language policies, and policies about immigrant status send a very different message about the value of cultural and linguistic pluralism. Below, we briefly describe three more articles in the ijme special issue that serve as examples of how the argument for resource pedagogies can be both theorized and practiced in the classroom. We follow these descriptions with a brief account of one of our own research projects to further elaborate on the value of a resource-pedagogies perspective to support the education of immigrant students.

In the article entitled, “Sobresalir: Latino Parent Perspectives on New Latino Diaspora Schools,” Sarah Gallo and Stanton Wortham (2012) adopt a counter-storytelling approach as part of a participatory action research video project with bilingual Latino immigrant parents. The researchers integrate aspects of critical race theory with elements of resource pedagogies in their collaborative work with the parents to produce videos designed to inform teachers about how to better foster communication and relationship building with recently arrived Latino immigrant parents such as themselves. The video incorporated the voices of bilingual parents as they discussed the linguistic and cultural challenges of supporting their children's schoolwork on the one hand, and, on the other, their concerns about how to instill strong values and monitor their children's moral development in a new cultural environment.

In addition, the parents eloquently articulated their hopes that their children would not experience discrimination in school and that the teachers would safeguard their children from unequal treatment. These (very reasonable) fears expressed by the parents highlight just how challenging it can be to support resource pedagogies that require the resources of the “other” to be viewed as strengths, while at the same time there are those who continue to believe in and act on the assumptions of cultural deficit theories. In an encouraging development, however, Gallo and Wortham also document teachers' responses to the bilingual parents' perspectives, demonstrating the ways in which a number of the teachers began to find common ground with parents, recognizing that “they have the same hopes and dreams for their children that I have for mine.”

In a second example of both the value and the challenge of developing sound resource pedagogies, Keisha McIntosh Allen, Iesha Jackson, and Michelle Knight (2012) foreground the voices of West African immigrants through their article, “Complicating Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Unpacking West African Immigrants' Cultural Identities.” In addition to reminding us that the discourse about recent immigrants to the U.S. must extend beyond the Latino community, Allen, Jackson, and Knight challenge us to reflect on the role of generational differences as well as cultural and linguistic differences as we consider the meaning of culturally relevant pedagogy. Using an interpretive in-depth interview design, the researchers conducted case studies with 18 second-generation and 1.5-generation West African immigrants –1.5 generation immigrants are those who immigrated in mid-childhood.

As Allen, Jackson, and Knight explored the ways in which their participants negotiated hybrid black identities incorporating both their West African heritages and their U.S. American sociocultural contexts, they discovered several themes that can help us to reimagine key aspects of resources pedagogies. Perhaps most importantly, these young adult participants insisted on the heterogeneity of black immigrant experiences that challenged stereotypical views of African values, knowledge, and ideologies. Thus, an expanded vision of culturally relevant pedagogy, posited to support students and educators in answering back to anti-immigrant discourses, must engage the fluid identities and contradictory knowledges held by multi-culturally and multi-lingually diverse groups of immigrant students, such as the self-portrayals of the West African immigrants in this study.

A third example of how resource pedagogies can be used to challenge anti-immigration discourses in education contexts is the study conducted by Morna McDermott, Nancy Shelton, and Stephen Mogge (2012) entitled, “Pre-service Teachers’ Perceptions of Immigrants and Possibilities of Transformative Pedagogy: Recommendations for a Praxis of Critical Aesthetics.” Their investigation of the learning experiences of 78 pre-service teachers destined to teach immigrant students in the northeastern United States integrated arts-based pedagogy and ethnographic methods through a workshop designed as a series of aesthetically grounded experiences. They incorporated drama, children's literature, and immigrant first-person narratives, with the goal of bringing to light and disrupting unexamined assumptions about immigration and immigrants in their pre-service educators.

They documented how some of these pre-service teachers moved beyond initial expressions that cast immigrants in a negative light (for example, as “stealing jobs,” “using our resources,” and “dirty”) to expressing more positive descriptors, such as “seeking opportunity,” “hard-working,” and having a “desire for education.” McDermott, Shelton, and Mogge caution that efforts such as single-session workshops can only begin a process whereby new teachers commence with a challenging transformation that might lead to meaningful relationships with immigrant students and families in their future classrooms. Still, such a process can be critical to helping teachers –whether new or experienced– examine their implicit or explicit cultural deficit or cultural difference views and then take the first steps toward embracing resource pedagogies.

Immigration Discourses in the Southeastern U. S. Region: Second CaseTo further illustrate how a resource pedagogy approach can support equitable education for immigrant students, we present a brief description of our Language-Rich Inquiry Science with English Language Learners (lisell) project. lisell is an ongoing research and implementation project to develop and test both a pedagogical model and a professional learning framework to support science inquiry practices and academic language practices for all students, with particular attention to Latino/a immigrant students and other English learners. Teachers in the southeastern United States have generally received little if any professional preparation to meet the needs and build on the resources that English learners bring to their classrooms. Thus, one of the project's overarching goals is to help teachers, students, families, and researchers learn from and with each other about the strengths and resources, as well as the needs and aspirations, that members of each group bring to the shared endeavor of supporting immigrant students' academic success.

The lisell pedagogical model is composed of six science and language practices meant to help all students, and particularly English learners, to develop proficiency using the language of science, and then use that language to reach their academic goals. The model is built upon a systemic functional linguistics view of language (Halliday, 2004), research on scientific reasoning (Kuhn, 2005), and our own exploratory work leading up to this project (Buxton et al., 2013).

The lisell professional learning framework was developed to help teachers take ownership and make use of the lisell pedagogical model to meet their needs and the needs of their students. The framework has five components, in each of which we facilitate opportunities for different groups of participants to position themselves in different ways for different purposes. For example, in the professional learning spaces of Grand Rounds classroom observations, the teachers are positioned as collaborators observing their peers and being observed in turn; the researchers are positioned as part of an observation team learning how project practices are enacted in classrooms; and the students are positioned as capable learners in cognitively and linguistically rich classroom spaces.

In the Steps to College through Science Bilingual Family Workshops, the teachers are positioned as participant observers, Spanish language learners, and advocates for their students; the researchers are positioned as facilitators, listeners, and learners across both organized and impromptu learning experiences; the students are positioned as bilingual learners engaged in authentic science practices and on a path to academic success; and the family members are positioned as active learners and teachers fully engaged in their children's academic success. In the spaces of the lisell assessment workshops, the teachers are positioned as assessment experts and reflective practitioners, while the researchers are positioned as trainers in interpretation of assessment responses and reflections on learning from student writing, and the students are positioned (through their written responses on the assessments) as critical thinkers learning to use the language of science to express their understanding of inquiry practices and of science content knowledge.

When taken together, we view our lisell pedagogical model and professional learning framework as a network of support for teachers, immigrant students, and their families through the creation of multiple spaces and tools for identifying, building on, and giving voice to the identities that immigrant students wish to express. Along with the other studies in this section, this work highlights both the progress that educators have made in moving from a deficit to a resource perspective and some of the challenges involved in forwarding a project of “supporting linguistic and cultural dexterity and plurality” (Paris, 2011).

As we continue to raise questions about how best to balance linguistic, cultural, and literacy tools that are valued in academic spaces with those valued in homes and communities, we should remember that teachers have significant power to influence the tone of how immigrants are perceived in their classrooms and schools, and by extension, their broader communities. Thus, work with teachers continues to represent a critical front line in efforts to challenge anti-immigration discourses in school and community contexts. In the previous sections, we have presented brief reviews of multiple research studies engaged in social justice work involving issues of immigrant rights. Each group of researchers used praxis approaches informed by critical discourse analysis, critical race theory, and/or resource pedagogies. In the final section we briefly summarize the need for continued research and action in multiple settings to both better understand the multi-dimensional nature of immigration and education and to better meet the needs of immigrant students and communities.

A Continuing Need for Interdisciplinary and Cross-National Perspectives on ImmigrationRecent publications on immigration show that there is a clear and ongoing need for timely research across disciplines that offer new theoretical perspectives and directions for social, political, and economic policy associated with twenty-first century movements and settlement of peoples across North America. In 2011, for example, Levine and LeBaron edited a special issue of Norteamérica that mapped the terrain of immigration policy, patterns of settlement, and frictions in communities in the southeastern United States, the location of some of the most recent and dramatic growth in immigration in the country. In recent editions of this journal, one article outlined the broader historical and theoretical perspectives on migration between Mexico and the United States (Genova, 2012); another study explored migration trajectories from Central America to the southeastern U.S. (Leon, 2012); and a third looked at the mapping of the circulating departure and return pathways for women from Puebla, Mexico, to North Carolina and back (Buznego, 2012).

Our current review of educational theory, research, and practice expands on this earlier work to offer the educational arena as a dynamic context in which to explore potentials and possibilities for new theory and praxis related to migration and immigration. Drawing on this educational research as well as the interdisciplinary cross- national work on immigration published previously in Norteamérica may provide new tools to counteract the effects of the rising tide of anti-immigration discourse in public policy and the media in the United States and Europe. The need for such tools becomes urgent in light of anti-immigrant violence erupting regularly in countries ranging from Mexico (Animal Politico, 2013) to Greece (Antiuk, 2012), to the U. S. (The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, 2009). Indeed, informed by approaches such as those explored in this article, we in the educational research and praxis community must further challenge ourselves to take creative and courageous action in our work with immigrant, multicultural, multilingual families and the educators who work with them. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith (1999), an Indigenous woman investigating decolonizing methodologies, states, Taking apart the story, revealing underlying texts, and giving voices that are often known intuitively does not help people improve their current conditions. It provides words, perhaps, and insights but it does not prevent someone from dying. (3)

As stated in United States v. Alabama, 691 F.3d 1269 (11th Cir. 2012), Alabama schools were required to determine whether an enrolling child “was born outside the jurisdiction of the United States or is the child of an alien not lawfully present in the United States” (Id. § 31–13–27(a)(1). A settlement of several lawsuits by various groups in November 2013 resulted in blocking this section of the law, among other sections.