This paper presents the results of a study aimed at identifying and assessing positive parenting programmes and activities carried out in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country (ARBC), Spain. The study is a development of the III Inter-institutional Family Support Plan (2011), drafted by the Basque Government's Department of Family Policy and Community Development, and its aim is to offer a series of sound criteria for improving existing programmes and ensuring the correct design and implementation of new ones in the future. It analyses 129 programmes and gathers data relative to institutional management and coordination, format, quality of the established aims, adaptation to the theoretical proposal for an Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum, scientific base, use of the framework of reference for competences, working method, assessment techniques, budgets and publicity, among others. The results highlight the good quality of the programmes’ aims and content, and the poor systematic assessment of these same aspects. The study concludes with a series of recommendations for improving the initiatives, integrated into a proposal for a system of indicators to assess and implement positive parenting programmes.

En este trabajo se presentan los datos de un estudio de identificación y valoración de programas y actividades de parentalidad positiva llevados a cabo en el ámbito de la comunidad autónoma del País Vasco (CAPV). El estudio constituye un desarrollo del III Plan Interinstitucional de Apoyo a la Familia (2011), elaborado por la Dirección de Política Familiar y Desarrollo Comunitario del Gobierno Vasco, y su objetivo es ofrecer criterios sólidos para mejorar los programas existentes y para lograr un correcto diseño e implementación de nuevos programas en el futuro. En el estudio se analizan 129 programas y se obtienen datos relativos a la gestión y coordinación institucional, formato, calidad de los objetivos, ajuste a la propuesta teórica del currículo óptimo de parentalidad positiva, fundamentos científicos, utilización del marco de referencia de las competencias, metodología de trabajo, prácticas de evaluación, presupuestos, publicidad, etc. Entre los resultados destacan la buena calidad de los objetivos y contenidos de los programas y la baja práctica de evaluación sistemática de los mismos. El trabajo concluye con una serie de recomendaciones para mejorar los programas, integradas en la propuesta de un sistema de indicadores para la evaluación e implementación de programas de parentalidad positiva.

This paper presents the results of a study commissioned by the Basque Government's Department of Family Policy and Community Development from the Haezi-Etxadi working group at the University of the Basque Country. This request to carry out an inventory of positive parenting activities and programmes forms part of the implementation of the III Inter-institutional Family Support Plan (2011–2015), which was approved by the Basque Government (Basque Government, 2011a) and is supported by diverse documents outlining the situation of families in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country (ARBC) in Spain, including the Diagnosis for the III Inter-institutional Family Support Plan (2011b). The Plan also encompasses data from other documents, including the System of Indicators for Monitoring the Situation of Children and Adolescents in the ARBC (Basque Government, 2010a), the publication entitled Approach to the Needs and Demands of Children and Adolescents in the ARBC (Basque Government, 2010b) and, finally, the Diagnosis of Childhood and Adolescence in the ARBC (Basque Government, 2011c).

In light of the data presented in the aforementioned documents, a series of different measures and references regarding positive parenting were included in the III Inter-institutional Family Support Plan (Basque Government, 2011a). Measure 101 of the Plan proposes the establishment of new evidence-based positive parenting proposals for developing parenting skills and competences, following the identification and assessment of initiatives already up and running in the ARBC. Measure 101 is complemented by the proposal to establish a positive parenting resource bank in collaboration with scientific researchers, to be placed at the disposal of all professionals working in this field. This present study presents the results of the prior assessment of the positive parenting programmes and activities currently existing in the ARBC, as part of the effort to implement measure 101 of the III Inter-institutional Plan.

The establishment of positive parenting policies is justified, firstly, by empirical evidence showing the significant influence of family context on psychological development. Part of this evidence was obtained in studies conducted in the ARBC (Arranz, Oliva, Sánchez, Olabarrieta, & Richards, 2010; Oliva, Arranz, Parra, & Olabarrieta, 2014). Secondly, said policies are informed by data which link certain family variables with the development of adaptation problems and pathologies throughout the course of an individual's entire life cycle (Van Loon, Van de Ven, Van Doesum, Witteman, & Hosman 2014), as well as by evidence regarding the characteristics and problems of families with dependent children in the ARBC. However, the most general justification lies in the efficacy and cost-effectiveness demonstrated by many parenting skill development programmes (Asmussen, 2011; Morrison, Pikhart, Ruiz, & Goldblatt, 2014).

The scientific basis upon which the development of positive parenting policies rests is made up of the body of research showing the decisive influence that a high-quality family context has on people's healthy psychological development, with this influence being significant from the prenatal stage onwards (Roncallo, Sánchez de Miguél, & Arranz, 2015). In the ARBC specifically, social intervention through positive parenting practices is also indicated for a number of demographic circumstances and reasons linked to relations within Basque families. The documents cited above (Basque Government, 2010a, 2010b; Basque Government 2011a, 2011b, 2011c) underscore the high percentage of single-parent families with dependent children living in the region (40% of all single-parent families, and 3% of all Basque families in general). Given that these families are more likely to be at risk of exclusion, it is evident that they should be the target of diverse support measures, including positive parenting initiatives. It is also significant that 18.8% of families claim to be experiencing serious problems of some kind with their dependent children (−18). Data regarding family communications are also worth noting, since, in general terms, communication appears to be difficult with fathers (38% of those interviewed in the survey conducted claimed to have problems talking to their father about the issues that concern them) and much more fluid with mothers (only 14% reported having problems talking to their mother). It is also important to mention that, in 2010, 9500 minors were treated by the mental health services operating in the three provinces of the ARBC.

Although the number of separations and divorces in families with dependent children dropped significantly between 2005 and 2009 (1000 fewer cases), in 2009 a total of 2088 couples with dependent children separated. In many cases, the separation and divorce process itself indicates that the children in question are exposed to conflict between their parents, an experience which has one of the greatest negative impacts on children's psychological adjustment. Other indicators of conflict include cases of missing minors (1260 in 2010, although most of them were found in that same year), the increase in cases of parental abuse by children (49 in 2007) and cases of child abuse in the family environment (395 in 2010).

Other data worth mentioning include those linked to the early consumption of alcohol and other substances; the mean age at which minors first start to consume alcohol in the ARBC is 13, and almost 20% of under 18s living in the region drink alcohol on a weekly basis. Moreover, 26% of the Basque population aged between 15 and 19 say they engage in at-risk or heavy drinking at weekends. In addition to this, 20% of the population aged between 15 and 19 are cannabis users, and 43.8% admit to having experimented at some time or another with the drug. Finally, the documents Basque Government (2011b, 2011c) indicate that Basque families tend to be overprotective in their parenting style.

In accordance with the legal cover provided by the III Inter-institutional Family Support Plan, as well as with available scientific data regarding the effectiveness of positive parenting programmes as preventive measures for the emergence of diverse pathologies throughout individuals’ psychological development (Gardner, Montgomery, & Knerr, 2015), the decision was made to assess current positive parenting programmes and activities. The justification for this decision was a desire to use public resources more efficiently, and precedence for this can be found in the literature, particularly in the work of Layzer, Goodson, Bernstein, and Price (2001), who conducted a national survey of family support programmes using quality criteria very similar to those used here, including those linked to programme assessment and the scientific basis of the initiative, among others. Other significant precedents include the works by Lundahl, Risser, and Lovejoy (2006) and Kaminski, Valle, Filene, and Boyle (2008), both of whom carried out meta-analyses on the efficacy of parent education programmes, highlighting the importance of the formats and methodologies with which said programmes are implemented. Another interesting work in this sense is the study by Scott (2010), who reported that programmes in the United Kingdom were not implemented rigorously enough, and underscored the importance of an initiative to found a national academy of professionals working in the field of parent education programmes.

In light of the basic situation outlined above; the following aims were therefore established for this present study: (1) to identify and assess positive parenting programmes underway in the ARBC in 2012; and (2) to propose improvements for existing programmes and guidelines for the correct design of future ones, with the aim of ensuring that future parenting education programmes comply with feasibility, efficacy and efficiency criteria. Evidence-based parent education programmes should be based on systematic research and should be reviewed and assessed in accordance with the criteria of significance and representativeness, providing both short and long-term information regarding the meeting of targets. Aims should be established on the basis of scientific knowledge regarding child development and optimum parenting practices. Similarly, details of how the programme is implemented should be clearly recorded, along with evidence of its efficacy (Asmussen, 2011; Morrison et al., 2014; Ponzetti, 2016).

MethodParticipantsIn order to fulfil the established aims, the first step was to define the inclusion criteria for participating programmes. The selected criteria were as follows: preventive programmes/activities aimed at the general medium-low risk population of parents with children aged between 0 and 18. Programmes also had to have content aimed at training families in parenting skills and have been implemented by the social services and/or education departments of Local Councils and Associations of Local Councils, or by non-for-profit associations working with families. The study comprises all positive parenting programmes implemented in municipalities with over 25,000 inhabitants. It also encompasses all programmes implemented by all the associations of local councils (i.e. groupings of smaller local councils) existing in the ARBC and non-for-profit associations working with families. These include third sector organisations such as civil associations, foundations, cooperatives and professional associations, among others. The list of these entities was provided by the Basque Government Department of Family Policy and Community Development.

A total of 129 positive parenting programmes and activities, implemented by 46 different entities (local councils, associations of local councils, provincial councils and non-for-profit associations), were assessed by the study. The distribution of positive parenting programmes among the three provinces of the ARBC was as follows: 57 in Biscay (44.1%); 49 in Álava (38%); 18 in Guipúzcoa (14%) and 5 from throughout the whole region (3.9%).

InstrumentInformation about each programme was gathered by means of a structured interview consisting of 86 questions regarding different issues, divided into the following information blocks: (1) programme's origin and institutional location (questions 1–17); (2) allocated budget, users, type of assessment method used, needs covered and language in which activities are conducted (questions 18–30); (3) aims, content, material, methodology, format, quality of the working method with families and the scientific basis of the activities carried out (questions 31–43); (4) organisational chart, publicity, funding, beneficiaries, the professionals implementing the programme and collaboration with other entities (questions 44–66); (5) specific positive parenting contents used in the programme (questions 67–86). The complete version of the interview administered can be found in the document containing the full technical report for this study (Basque Government, 2012).

In addition to the assessment carried out by the managers of their programme's aims, content, materials, methodology and scientific basis, in order to facilitate subsequent processing, a mean assessment score of between 0 and 10 was also awarded by interviewers to each programme or activity (external evaluation). This score was based on the existence or absence of diverse quality indicators. In relation to the aims, the indicators taken into account included vocabulary formulated in terms of competences, conceptual clarity and precision and adaptation to positive parenting guidelines. In relation to content, interviewers assessed adaptation to positive parenting guidelines, conceptual clarity and precision and thoroughness. As regards materials, their existence or absence was taken into account, along with their quality and adaptation to positive parenting guidelines. In relation to working methodology with families, quality was considered, alongside adaptation to a constructivist, experimental and group-based working approach. Finally, as regards scientific basis, interviewers assessed the programme's scientific and theoretical pillars, the existence of scientific literature attesting to its efficacy and the quality of the assessment procedure employed.

ProcedureOnce the list of participating entities had been compiled, each entity was contacted by either telephone or e-mail with the aim of informing them of the project and requesting their collaboration. Interviews were held in the language chosen by each participating entity. All entities from each of the three groups were interviewed individually, and although a common protocol (outlined below) was used in all cases, with the aim of gathering as much information as possible and facilitating the participation of the individuals involved, said protocol was adapted to the specific needs of each interviewee. The formal interview protocol was as follows:

Information about the project: an e-mail message was sent to the person responsible for social services and/or education at the local council or association of local councils, or to the head of the non-for-profit association, informing them of the project and requesting their collaboration.

Unification of criteria: a telephone conversation was held with the person responsible for the programme, with the aim of ensuring the information had been correctly received and to check whether the programme fulfilled the criteria established for inclusion in the study.

Interview format: the heads of all the programmes identified were given the opportunity to choose which interview format they preferred. The options offered were: face-to-face interview, telephone interview or questionnaire sent by e-mail, with help being provided to ensure its correct completion, either by telephone or through e-mail correspondence. Participants were also offered the option of jointly compiling the information alongside the interviewer; in other words, the interviewer gathered the information available about the programme on the institution's website, and then adapted it to the interview format; subsequently, a copy was sent to the interviewee, who added any further relevant details and jointly supervised the final result. This flexibility in the data gathering process was absolutely vital, since participating professionals were being asked to collaborate on a voluntary, non-remunerated basis. The predominant professional profile of informants was that of a university graduate in the field of social science.

ResultsA certain imbalance was observed in relation to the distribution of public positive parenting programmes among the three provinces of the ARBC. Proportionally speaking, Álava has the most programmes and activities. Occasionally, very similar programmes were found in the different departments of the same local council, with no coordination whatsoever between them, not even in terms of disseminating said activities among the target population.

The data gathered in relation to assessment reveal that most programmes are evaluated by the same institutions that run them, and only 14 programmes (10.9%) are assessed by external agents. The most widespread form of assessment is user satisfaction. The results reveal that approximately 26 programmes (20.2%) are not subject to any kind of assessment other than user satisfaction and 13 (10.1%) are not evaluated at all, not even by means of user satisfaction surveys.

The results regarding the way in which programmes are implemented indicate that 96 (76%) use a traditional, face-to-face format, 14 (11%) are on-line programmes, 6 (4.5%) have a mixed design (face-to-face and on-line group work) and 13 (8.5%) are mixed with individual on-line interaction.

As regards budget, 86 programmes (66.7%) operate with a total budget of less than €36,000, while 52 programmes (40.3%) have a budget of €6000 or less. It should be noted that budget information was unavailable for 15.5% of the programmes studied.

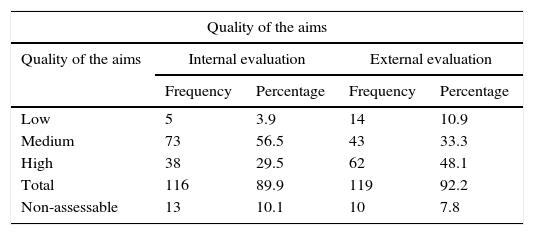

In relation to the assessment of the quality of the aims set, institutional evaluations gave mid-level scores, while the external evaluations (i.e. those carried out by the research team conducting the interviews) awarded more programmes a lower score, and gave those assessed as mid-level by the institutions themselves a lower rating. Nevertheless, the external evaluations awarded high scores to almost 50% of all programmes, and 81.4% were scored as acceptable, while only 10.9% were rated as low. The results regarding the quality of the aims as assessed by the people responsible for the programmes and by the research team (external evaluation) are provided in Table 1.

Quality of the aims, content and working methodology.

| Quality of the aims | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of the aims | Internal evaluation | External evaluation | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Low | 5 | 3.9 | 14 | 10.9 |

| Medium | 73 | 56.5 | 43 | 33.3 |

| High | 38 | 29.5 | 62 | 48.1 |

| Total | 116 | 89.9 | 119 | 92.2 |

| Non-assessable | 13 | 10.1 | 10 | 7.8 |

| Quality of the content | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of the content | Internal evaluation | External evaluation | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Low | 7 | 5.4 | 17 | 13.2 |

| Medium | 69 | 53.5 | 69 | 53.5 |

| High | 37 | 28.7 | 31 | 24 |

| Total | 113 | 87.6 | 117 | 90.7 |

| Non-assessable | 16 | 12.4 | 12 | 9.3 |

| Quality of the working methodology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of the working methodology | Internal evaluation | External evaluation | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Low | 8 | 6.2 | 19 | 14.7 |

| Medium | 68 | 52.7 | 56 | 43.4 |

| High | 35 | 27.1 | 23 | 17.8 |

| Total | 111 | 86 | 98 | 76 |

| Non-assessable | 18 | 14 | 31 | 24 |

| Total (N) | 129 | 100.0 | 129 | 100.0 |

The assessment of the quality of the programme content revealed that over 75% of said content was rated as medium to high by the external evaluators, while 13.2% was classed by the same evaluators as being of low quality. In relation to both the content and the aims, the programmes that are classed in the tables as non-assessable are those for which not enough information regarding these aspects was available to enable evaluation. In many cases, this is because the relevant information is not formulated in explicit terms or in writing. The results referring to content quality are provided in Table 1.

In relation to the methodology used in the programmes, the most popular was the group method, employed by 75 programmes (58.1%), followed by individual work (33 programmes, 25.6%) and the mixed method (12 programmes, 9.3%). The remaining 9 programmes failed to provide adequate information regarding their methodology. The quality of the methodology used was comparatively lower than the quality of the aims and content. However, it should be pointed out that this is not due to the poor quality of the procedures themselves, but rather to the fact that they were assessed from the perspective of their effectiveness for ensuring that parents acquire one or various parenting skills. The results referring to the quality of the methodology used are presented in Table 1.

The information gathered regarding the scientific basis of the programmes revealed that 105 programmes (81.4%) are based on scientific findings; 14 (10.9%) have no scientific base whatsoever and 10 (7.8%) failed to offer reliable information about this aspect. Therefore, in general, the aims and content of the programmes are consistent with the results obtained by systematic research into family contexts that constitute either protective or risk factors for psychological development. Nevertheless, in the future, the scientific basis of the programmes may be improved even more by measuring their impact on the populations in which they are implemented, thus obtaining empirical evidence of their efficacy.

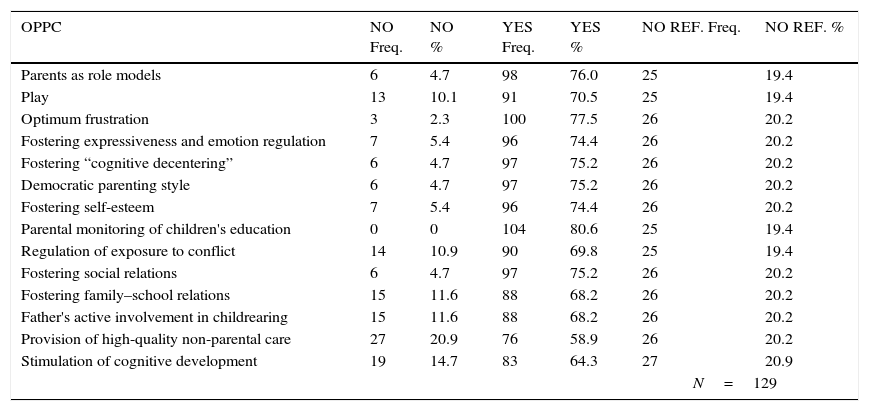

As regards adapting the programme content to the framework of the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum, the results reveal that the majority of programmes encompass variables and competences that are key elements of positive parenting practice. However, certain contents are less well-represented than others. These include Provision of high-quality non-parental care, Stimulation of cognitive development, Father's active involvement in childrearing, Fostering of family–school relations, Regulation of exposure to conflict and Play. Some programmes were also found to have content not explicitly included in the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (OPPC), although said content is included in some of the curriculum's variables and competences. This is the case with programmes focused on effective conflict resolution, which in the OPPC is considered part of the democratic parenting style. Nevertheless, the importance of low exposure to conflict is a content that should be included in all generic positive parenting programmes. The data regarding each programme's adaptation to the content of the OPPC are presented in Table 2.

Adaptation to the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (OPPC).

| OPPC | NO Freq. | NO % | YES Freq. | YES % | NO REF. Freq. | NO REF. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents as role models | 6 | 4.7 | 98 | 76.0 | 25 | 19.4 |

| Play | 13 | 10.1 | 91 | 70.5 | 25 | 19.4 |

| Optimum frustration | 3 | 2.3 | 100 | 77.5 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Fostering expressiveness and emotion regulation | 7 | 5.4 | 96 | 74.4 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Fostering “cognitive decentering” | 6 | 4.7 | 97 | 75.2 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Democratic parenting style | 6 | 4.7 | 97 | 75.2 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Fostering self-esteem | 7 | 5.4 | 96 | 74.4 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Parental monitoring of children's education | 0 | 0 | 104 | 80.6 | 25 | 19.4 |

| Regulation of exposure to conflict | 14 | 10.9 | 90 | 69.8 | 25 | 19.4 |

| Fostering social relations | 6 | 4.7 | 97 | 75.2 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Fostering family–school relations | 15 | 11.6 | 88 | 68.2 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Father's active involvement in childrearing | 15 | 11.6 | 88 | 68.2 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Provision of high-quality non-parental care | 27 | 20.9 | 76 | 58.9 | 26 | 20.2 |

| Stimulation of cognitive development | 19 | 14.7 | 83 | 64.3 | 27 | 20.9 |

| N=129 | ||||||

In relation to the programme beneficiaries, in 115 cases (89.1%), activities are targeted at all types of families, 2 programmes (0.8%) are more specific and 12 (9.3%) failed to provide adequate information in this respect. These results reveal the universal nature of the programmes analysed in the study. Even when they are focused on one specific aspect of positive parenting, such as conflict, for example, they are targeted at the general population, with all the variability that this implies. As regards age or development stage, only 11 (8.5%) programmes focus specifically on the childhood period, 21 (16.2%) focus on adolescence, 88 (68.3%) contemplate both periods and 9 (7%) failed to provide adequate information in this respect. Of those focusing specifically on childhood, the most significant finding was the low frequency of programmes centred around the 0–3 age group, and the total absence of systematic programmes focused on the prenatal period.

DiscussionAn initial general assessment of the results of the study revealed that the tool used for evaluating positive parenting programmes and activities in the ARBC was sensitive enough to detect differences in the quality of the programmes studied. The programme assessment criteria were based on the findings of prior scientific literature, including those reported by Asmussen (2011), Scott (2010) and Kaminski et al. (2008), and were proven to be effective in this present study. The set of variables proposed in the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum opens up future avenues of research focusing on the real influence of diverse parenting skills on different aspects of children's development, including academic performance and mental health.

In addition to the quantitative data collected, the results of this study require certain qualitative assessments in order to enable the establishment of sound action proposals within the field of positive parenting. This section outlines the most relevant of these.

Lack of knowledge regarding the legal framework and contents of positive parentingAlthough many interviewees were well-qualified professionals with ample experience in the field of family training and programme management, in general they were largely unaware of the existence, contents and approach of the new European legal framework for positive parenting. Two of the key issues of which many professionals were unaware were the universal approach adopted by positive parenting actions (i.e. the fact that they do not focus exclusively on at-risk populations) and their similarities to public health strategies.

Absence of a previously-established positive parenting curriculumPositive parenting, understood as the set of actions and practices engaged in by parents to foster their children's healthy psychological development, is manifested through a series of competences which parents must acquire in order to generate family contexts that strengthen protective factors, minimise risks and have a positive impact on the quality of psychological development. This set of competences has already been established by researchers working in this field. If the aim of positive parenting policies is for families to acquire the aforementioned set of competences, then one clear conclusion can be drawn from the assessment of the programmes analysed in this study, namely that very few use a global approach that includes an effort to help families acquire all the competences which make up the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (Basque Government, 2012).

The majority of programmes focus on one single competence or characteristic of the family environment, and impart guidelines relative to, for example, the father's involvement or the importance of play. What they fail to do, however, is to adopt a comprehensive, systematic approach aimed at helping parents become competent childrearers. This shortcoming results in a dispersion of not only the contents, but also the beneficiaries of these policies; it may be that, for example, a family will be trained in one important competence, but receive no training or information about other, equally relevant skills.

Greater frequency of family training activities resulting from demands by the families themselvesThe study encompasses programmes and activities with different approaches. In general, it can be concluded that dissemination and information activities (e.g. talks and written documents) are targeted at the general population, while the more structured strategies (e.g. programmes) are targeted at more specific parts of the population. The activities aimed at specific groups often stem from demands made by a group of families, as well as from the identification of training needs by the institutions working in the field of family intervention. In light of this situation, in the future it would be a good idea for the set of positive parenting programmes offered by a specific community to include both activities targeted at the general population, which would strive to convey a global set of minimum competences, and more specific programmes designed to respond to concrete demands from specific groups.

Absence of any conceptual organisation of the programme aims in terms of competencesThe positive parenting programmes and activities analysed in this study were very varied in nature, with a wide range of different aims, content and methodologies. Some formulated their aims correctly, using terms that can easily be understood by beneficiaries. This results in much more effective communication. However, for communications between professionals, it would be best to use a common technical language expressed in terms of competences. The use of this common language would not only facilitate communication between professionals, but would also enable a much more rigorous assessment of the programmes in question. The structuring of programme aims and content in terms of competences is fully compatible with the different training procedures targeted at parents, even those which adopt a more dynamic, group-based approach.

Assessment of existing programmes’ adaptation to the educational demands detected in previous studiesOne of the most interesting qualitative results of this study is the finding that substance abuse prevention services are highly aware of and sensitive to positive parenting programmes. This indicates widespread knowledge among professionals of the close connection which exists between parenting practices and substance abuse and self-regulation in general. In this sense, the institutional policies analysed were found to provide an adequate response to a specific need.

One of the family circumstances mentioned in the introduction to this paper refers to the need for greater support to be provided to single-parent families. Insofar as, in many cases, these families are made up of single mothers with low economic-educational resources, they should be the target of specific programmes designed to provide comprehensive, systemic educational support. In general, there are no concrete programmes targeted exclusively at these families, but they are eligible to become beneficiaries of existing programmes run by diverse institutions, which focus on issues highly relevant to them, such as, for example, family meeting points or programmes which support the separation and divorce process. One such programme particularly worth mentioning is the family mediation service offered by the Basque Government.

This said, certain important aspects of positive parenting were found not to be sufficiently reflected in the programmes and activities analysed in this study. One of these is sex education, which despite constituting a key part of a few programmes, does not have the regular, structured presence it should, particularly in those programmes focusing on adolescence. Much the same can be said for other contents also, such as value transmission, the limiting of the time spent by children and adolescents in front of screens and the use of the Internet, in all its various guises.

As regards the response provided to the trend detected among Basque families to be overprotective (as mentioned in the introduction and based on the documents Basque Government 2011b, 2011c), many positive parenting programmes and actions dedicated specifically to this issue were observed in the ARBC. The majority of these initiatives focus on disseminating content outlining the importance of establishing rules and limits from very early ages, with the aim of ensuring that children learn to cope with frustration and regulate their own behaviour. The ability to regulate one's own behaviour stems from the presence of an external control mechanism manifested through rules and limits, which are gradually internalised by children. The educational challenge lies in ensuring that this internalisation is long-lasting. The effective laying down of rules and limits requires time and a mindset that many families lack. Consequently, systemic-ecological measures such as those designed to ensure a good work-life balance play a key role.

Absence of collaboration programmes involving both families and schoolsAlthough many positive parenting programmes and initiatives are carried out in schools, this does not mean that there is effective collaboration between both interactive systems. Indeed, we could even state that there is a certain degree of conflict between the two: education professionals demand that parents play a more active educational role, since many children fail to acquire the minimum competences required to ensure harmonious coexistence and autonomy; and parents demand a greater degree of intervention from schools. This problem has become more acute since children started attending school-run infant care centres at the age of 4 months, as is the case with children in the ARBC's public network of school kindergartens (Haurreskolak). There is an urgent need for schools and families to find a shared curriculum and for headway to be made in the field of collaboration programmes aimed at fostering joint action and co-responsibility between the family and school systems. This question has gained relevance recently in scientific research (Pourtois, Desmet, & Lahaye, 2013; Stormshak et al., 2016; Sheridan & Moorman Kim, 2016).

Need to move beyond the traditional parent education modelOne of the conclusions that can be drawn from the diverse interviews held with professionals working in the field of family intervention and parent training is the need to move beyond the traditional parent education model (parent schools), since this model tends to end up providing specific training for only a very select group of families. This means that families who would perhaps benefit most from positive parenting training often fail to receive it.

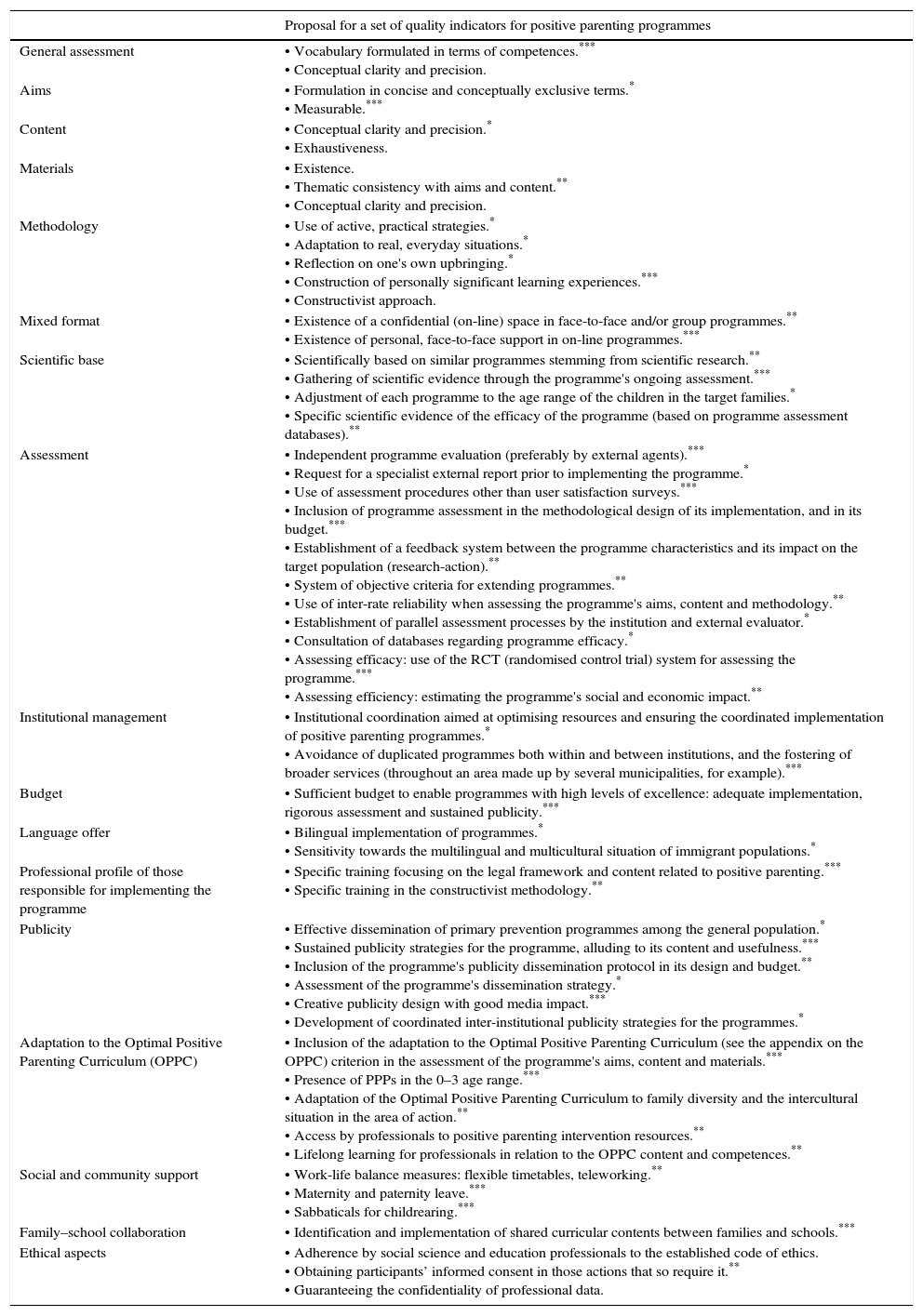

Table 3 presents a final summary of the study results, showing the system of indicators derived from it. Indicators marked with three asterisks are those for which serious deficiencies have been detected, and to which we recommend priority attention be given. Those marked with two asterisks are those for which medium levels of deficiency have been detected, and for which a medium priority level is recommended. Those marked with one asterisk are those for which only low levels of deficiency have been detected, and for which a low priority level is recommended. Finally, those with no asterisks are those for which the global assessment of the programmes was satisfactory.

Proposal for a set of quality indicators for positive parenting programmes.

| Proposal for a set of quality indicators for positive parenting programmes | |

|---|---|

| General assessment | • Vocabulary formulated in terms of competences.*** • Conceptual clarity and precision. |

| Aims | • Formulation in concise and conceptually exclusive terms.* • Measurable.*** |

| Content | • Conceptual clarity and precision.* • Exhaustiveness. |

| Materials | • Existence. • Thematic consistency with aims and content.** • Conceptual clarity and precision. |

| Methodology | • Use of active, practical strategies.* • Adaptation to real, everyday situations.* • Reflection on one's own upbringing.* • Construction of personally significant learning experiences.*** • Constructivist approach. |

| Mixed format | • Existence of a confidential (on-line) space in face-to-face and/or group programmes.** • Existence of personal, face-to-face support in on-line programmes.*** |

| Scientific base | • Scientifically based on similar programmes stemming from scientific research.** • Gathering of scientific evidence through the programme's ongoing assessment.*** • Adjustment of each programme to the age range of the children in the target families.* • Specific scientific evidence of the efficacy of the programme (based on programme assessment databases).** |

| Assessment | • Independent programme evaluation (preferably by external agents).*** • Request for a specialist external report prior to implementing the programme.* • Use of assessment procedures other than user satisfaction surveys.*** • Inclusion of programme assessment in the methodological design of its implementation, and in its budget.*** • Establishment of a feedback system between the programme characteristics and its impact on the target population (research-action).** • System of objective criteria for extending programmes.** • Use of inter-rate reliability when assessing the programme's aims, content and methodology.** • Establishment of parallel assessment processes by the institution and external evaluator.* • Consultation of databases regarding programme efficacy.* • Assessing efficacy: use of the RCT (randomised control trial) system for assessing the programme.*** • Assessing efficiency: estimating the programme's social and economic impact.** |

| Institutional management | • Institutional coordination aimed at optimising resources and ensuring the coordinated implementation of positive parenting programmes.* • Avoidance of duplicated programmes both within and between institutions, and the fostering of broader services (throughout an area made up by several municipalities, for example).*** |

| Budget | • Sufficient budget to enable programmes with high levels of excellence: adequate implementation, rigorous assessment and sustained publicity.*** |

| Language offer | • Bilingual implementation of programmes.* • Sensitivity towards the multilingual and multicultural situation of immigrant populations.* |

| Professional profile of those responsible for implementing the programme | • Specific training focusing on the legal framework and content related to positive parenting.*** • Specific training in the constructivist methodology.** |

| Publicity | • Effective dissemination of primary prevention programmes among the general population.* • Sustained publicity strategies for the programme, alluding to its content and usefulness.*** • Inclusion of the programme's publicity dissemination protocol in its design and budget.** • Assessment of the programme's dissemination strategy.* • Creative publicity design with good media impact.*** • Development of coordinated inter-institutional publicity strategies for the programmes.* |

| Adaptation to the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (OPPC) | • Inclusion of the adaptation to the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (see the appendix on the OPPC) criterion in the assessment of the programme's aims, content and materials.*** • Presence of PPPs in the 0–3 age range.*** • Adaptation of the Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum to family diversity and the intercultural situation in the area of action.** • Access by professionals to positive parenting intervention resources.** • Lifelong learning for professionals in relation to the OPPC content and competences.** |

| Social and community support | • Work-life balance measures: flexible timetables, teleworking.** • Maternity and paternity leave.*** • Sabbaticals for childrearing.*** |

| Family–school collaboration | • Identification and implementation of shared curricular contents between families and schools.*** |

| Ethical aspects | • Adherence by social science and education professionals to the established code of ethics. • Obtaining participants’ informed consent in those actions that so require it.** • Guaranteeing the confidentiality of professional data. |

One of the study's limitations are the deficiencies detected in the information gathering instrument itself, which became evident as interviews were held with the participating professionals. Nevertheless, all the relevant information provided by participants was included in the report, in either the quantitative part or the sections dedicated to the qualitative analyses. It should also be pointed out that although the vast majority of programmes included in the study focus on actions targeted at the general population, some do work specifically with families that may be considered a “pre-risk” group.

Another question to bear in mind is the representativeness of the sample group, which despite including the majority of positive parenting programmes and activities carried out in the ARBC, is not one hundred percent exhaustive. It is also important to remember that informants are not independent agents, and to a certain extent, their responses may be subject to the social desirability bias. Nevertheless, both the register and the assessment carried out in the study were based on quantitative and qualitative indicators that were as rigorous as possible.

As for the study's strengths, we should highlight the fact that the data were gathered by means of field research carried out in collaboration with the professionals responsible for actually applying the programmes in practice. Furthermore, the proposal of a new system of indicators for the design and assessment of positive parenting programmes and the development of an Optimal Positive Parenting Curriculum (OPPC) both constitute significant contributions that should be taken into consideration in the development of any future programmes within the field of positive parenting. Future research should strive to identify and assess those programmes not included in the original sample group of this study, located in towns and villages with less than 25,000 inhabitants.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the fact that, as a consequence of the findings of this study (Basque Government, 2012) the Basque Government Department of Family Policy and Community Development has set up a website called Gurasotasuna (Basque Government, 2013), which means “parenting” in the Basque language, on which interested parties can consult the system of indicators for evaluating programmes derived from this study. The website also constitutes a resource bank for professionals working in the field of positive parenting.

FundingThis study was funded by the Basque Government Department of Family Policy and Community Development, within the Regional Ministry for Employment and Social Affairs, in 2012.

Conflict of interestThe have no conflict of interest to declare.