The present study aimed to review recent literature on universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents. The following databases were used: Web of Science, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PubMed, LILACS, and SciELO. The keywords included the following: (Parenting Program or Parent Training or Parent Intervention) and (Maltreatment or Violence or Violence Prevention). For inclusion in this review, the programs had to be structured, working in groups of parents aiming to improve parenting practices. Twenty-three studies were included, and 16 different types of parenting programs were identified. Ninety-one percent of the studies were conducted in developed countries. All the programs focused on the prevention of violence and maltreatment by promoting positive parenting practices. Only seven studies were randomized controlled trials. All studies that evaluated parenting strategies (n=18), reported after the interventions. The programs also effectively improved child behavior in 90% of the studies that assessed this outcome. In conclusion, parenting educational programs appear to be an important strategy for the universal prevention of violence and maltreatment against children. Future studies should assess the applicability and effectiveness of parenting programs for the prevention of violence against children in developing countries. Further randomized control trials are also required.

El presente artículo pretende revisar la literatura actualizada acerca de los programas universales de educación parental de prevención de la violencia y el maltrato contra los niños. Las bases de datos utilizadas fueron Web of Science, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PubMed, LILACS y SciELO, con las palabras clave: parenting program or parent training or parent intervention and maltreatment or violence or violence prevention. Los programas eran estructurados, trabajando en grupos de padres para mejorar las prácticas educativas. Se incluyeron 23 estudios. La mayoría se llevó a cabo en los países desarrollados (91%). Se identificaron 16 diferentes programas de promoción de las prácticas educativas para prevenir la violencia y el maltrato infantil. Sólo siete estudios eran ensayos controlados aleatorios. Todos los estudios que evaluaron las prácticas educativas demostraron una mejoría después de la intervención (n=18). Los programas demostraron una mejora en el comportamiento de los niños en el 90% de los estudios que evaluaron este resultado. En conclusión, los programas educativos para padres demostraron ser una estrategia importante para la prevención universal de la violencia y el maltrato infantil. Se enfatiza la importancia de la implementación y evaluación de programas de educación parental en los países en desarrollo y más ensayos controlados aleatorios.

Violence threatens adaptive child development and can lead to mental and physical health problems, representing a high cost to society (Christian & Schwarz, 2011). Child maltreatment refers to the physical and emotional mistreatment, sexual abuse, neglect, and negligent treatment of children and their commercial or other exploitation (Butchart, Harvey, Mian, & Furniss, 2006). Violence against children is a substantial problem in both developed countries that have high-income economies and developing countries that have low- to middle-income economies, according to the classification of the World Bank (2015).

Children are negatively affected by experiences of maltreatment, abuse, and neglect (Cicchetti & Blender, 2006). These violent experiences during childhood have significant negative consequences on children's self-regulatory development (McCoy, 2013) and later mental health disorders (Jonson-Reid, Kohl, & Drake, 2012). Early negative experiences can impact genetic predisposition, brain architecture, and health in the long-term (Shonkoff & Garner, 2012).

Violence against children by adults within the family is one of the least visible forms of child maltreatment, but it is nonetheless widely prevalent in all societies (Butchart et al., 2006). In 2011, 80.8% of children were victims of maltreatment by parents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Compared with other health problems, the economic burden of child maltreatment is substantial, indicating the relevance of prevention efforts to address the high prevalence of this problem (Fang, Brown, Florence, & Mercy, 2012). However, there are particular difficulties when designing strategies for prevention in the family context because the perpetrators of maltreatment are also the source of nurturing for children (Butchart et al., 2006).

Intervention programs for children and families should begin as early as possible to reduce or avoid the need of most costly and less effective remediation programs (Arruabarrena & De Paúl, 2012). Interventions can be classified as the following: universal (which addresses the general public or an entire population group that has not been identified on the basis of individual risk), selective (which is directed toward at-risk groups or individuals), and indicated (which targets individuals with biological markers, early symptoms, or problematic behaviors that predict a high level of risk; O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009). Considering the difficulty in identifying child maltreatment within families, universal prevention programs can provide a great opportunity to prevent violence and maltreatment because they could be available to community-based populations. Additionally, undertaking universal prevention efforts that address all families avoids the risk of stigmatization (Byrne, Rodrigo, & Maiquez, 2014; Heinrichs, Kliem, & Hahlweg, 2014).

The main strategies to prevent child maltreatment include parenting programs that promote safe, stable, and nurturing relationships between caregivers and children at early ages (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; World Health Organization, 2009). These prevention strategies provide experiences and opportunities to parents so they can learn to develop effective parenting practices (Trivette & Dunst, 2009). Parenting educational programs can effectively prevent child maltreatment, abuse, and neglect by increasing parents’ knowledge of child development, improving parents’ child-rearing skills, and encouraging positive child management strategies (Mikton & Butchhart, 2009). The goals of a large portion of these programs do not focus specifically on violent behavior; they are instead designed to encourage healthy relationships and increase parental skills (World Health Organization, 2009). Therefore, in many evaluation studies, risk factors for child maltreatment (e.g., measures of child abuse potential, parental stress, or changes in parental attitudes toward disciplinary behavior) are used to assess the programs rather than direct measures (e.g., reports of child protective services; World Health Organization, 2009).

Previous reviews on parenting programs reported significant findings that are related to the effectiveness of these programs across parental and child outcomes, such as changing parenting behavior and preventing child behavior problems (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008; Rios & Williams, 2008), modifying disruptive child behavior (Lundahl, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2006), improving emotional and behavioral adjustment of children under three years of age (Barlow, Smailagic, Ferriter, Bennett, & Jones, 2010), and increasing parents’ psychosocial wellbeing in the short-term (Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff, & Bennett, 2012). However, these programs cited above did not specifically focus on the prevention of violence and maltreatment.

Some reviews have focused specifically on violence and maltreatment prevention interventions, including parenting programs and other types of interventions (Holzer, Higgins, Bromfield, & Higgins, 2006; MacMillan et al., 2009). Nonetheless, these reviews did not follow a formal systematic review process that utilizes an explicit and auditable protocol, including the mechanisms that were used to search, select, and retrieve reports (Sandelowski, 2008). Most recently, MacMillan et al. (2009) included articles up to only 2008; therefore, an updated systematic review on the relevant literature is needed. Notably, there is one relatively recent systematic review on the effectiveness of universal and selective child maltreatment prevention programs, but it was a review of review studies that were published up to July 2008, and it also did not focus exclusively on parental education programs (Mikton & Butchhart, 2009). Two other reviews focused on parenting programs but specifically focused on low- and middle-income economies (Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, 2013; Mejia, Calam, & Sanders, 2012).

Therefore, there are still gaps in the literature with regard to recent systematic reviews that focus on parenting intervention programs that are related to the universal prevention of violence and maltreatment. The present systematic review seeks to add to previous reviews on child maltreatment prevention, with a specific focus on universal prevention interventions through parenting educational programs in both developed and developing countries. The overall aim of this study was to critically examine recent empirical studies on universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents that were published between 2008 and 2014. The questions that guided this review were the following: (i) What is the geographical distribution of the studies? (ii) Which parenting educational programs have been conducted for the universal prevention of violence and maltreatment with parents or other caregivers of children? (iii) What are the experimental designs and methodologies used to assess the efficacy/effectiveness of these programs? (iv) What are the main findings after implementation of these parenting educational programs?

MethodsA systematic review of universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents was conducted based on principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). The review was conducted by searching the following databases: Web of Science, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PubMed, LILACS, and SciELO. The keywords that were used in the searches included the following: (Parenting Program or Parent Training or Parent Intervention) and (Maltreatment or Violence or Violence Prevention).

The filters that were used to refine the search results were the following: Web of Science (document type=article, timespan=2008–2014), PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES (document type=journal article, year=2008–2014), PubMed (publication date=2008–2014, species=humans, article type=clinical trial). All of the references and abstracts were included in an EndNote program for analysis.

Different types of parenting programs exist, along with a range of definitions. Therefore, the present review used the same definition of parenting educational programs that was used in another prior review (Kane, Wood, & Barlow, 2007), namely “interventions that utilize a structured format, working with parents in groups aimed at improving parenting practices and family functioning.” A “structured format” refers to programs that included a manual for implementation of the program, which explicitly explains what users need to provide in the program sessions. The structured format enhances the chances that the program will be adequately replicated in the future.

The inclusion criteria for the studies were the following: (i) empirical studies, (ii) universal prevention, including general populations, (iii) parenting educational programs for violence and maltreatment prevention, which directly or indirectly prevent violence and maltreatment through effective parenting practices, (iv) face-to-face programs, (v) parenting programs for parents of children, (vi) studies published from January 2008 to December 2014, and (vii) studies that were written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish.

Importantly, the inclusion criteria did not limit the studies according to their research design. A previous review by Mikton and Butchhart (2009) showed that many studies in this area did not use rigorous methodologies. Therefore, this could have excluded many studies in the present review. However, the present analysis considered whether the study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), which is a rigorous empirical design that evaluates treatment efficacy (APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2006). In contrast, non-randomized trials analyze the effectiveness of a program under conditions that are likely to occur in the real world, with less control of confounding variables compared with RCTs (O’Connell et al., 2009).

The exclusion criteria were the following: reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, case studies, empirical studies that did not address universal prevention, intervention programs of identified cases (e.g., children and adults who were exposed to family violence, mothers with a history of multiple forms of abuse, parents who received treatment for the use of substances like alcohol and drugs, and studies that had as an inclusion criterion risk assessment), intervention programs for specific populations (e.g., parents of adopted children, fathers who were not living together with their sons, and children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), parenting programs that were specific to parents of adolescents, empirical studies of parenting educational programs that used only books, videos, multimedia, or the Internet (i.e., were not face-to-face), and home-visitation programs.

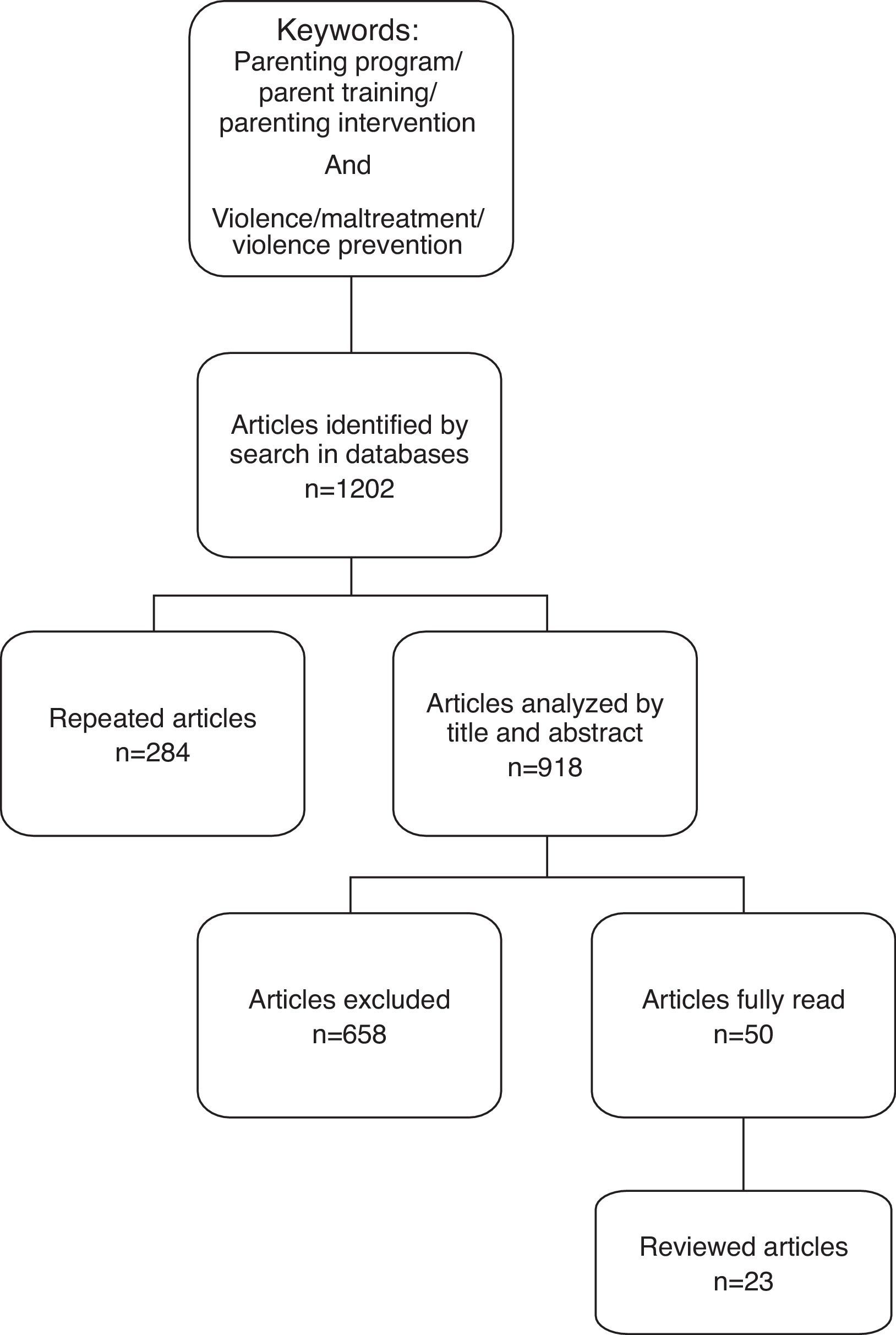

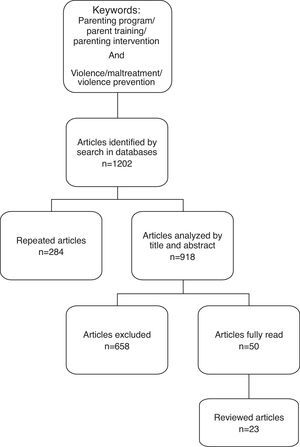

The initial searches yielded 1202 articles in the databases using the keywords above. First, duplicate articles that were indexed in more than one database were excluded (n=284). Second, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the remaining 918 abstracts, which excluded 658 articles. Third, the full text of the remaining 50 empirical studies on interventions for parents of children were read. After reading these articles, 27 were excluded for the following reasons: (i) intervention programs that addressed risk or specific samples, (ii) parenting educational programs with no face-to-face interactions with the facilitators of the groups, (iii) non-structured interventions, and (iv) home-visiting programs. The final sample included 23 articles.

The flowchart of the entire article selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

ResultsParenting educational programs to prevent violence and maltreatmentGeographical distribution of the studiesTwenty-one studies (91%) were conducted in developed countries. Most of these studies were performed in the United States (n=12; 52%), and the others (n=9; 39%) were performed in seven countries, including two in Japan, two in Spain, and one each in Australia, Portugal, Switzerland, Germany, and Canada. Only two studies (9%) were conducted in low- to middle-income countries. One study was conducted in Iran, and the other analyzed the results from nine countries, including Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Serbia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

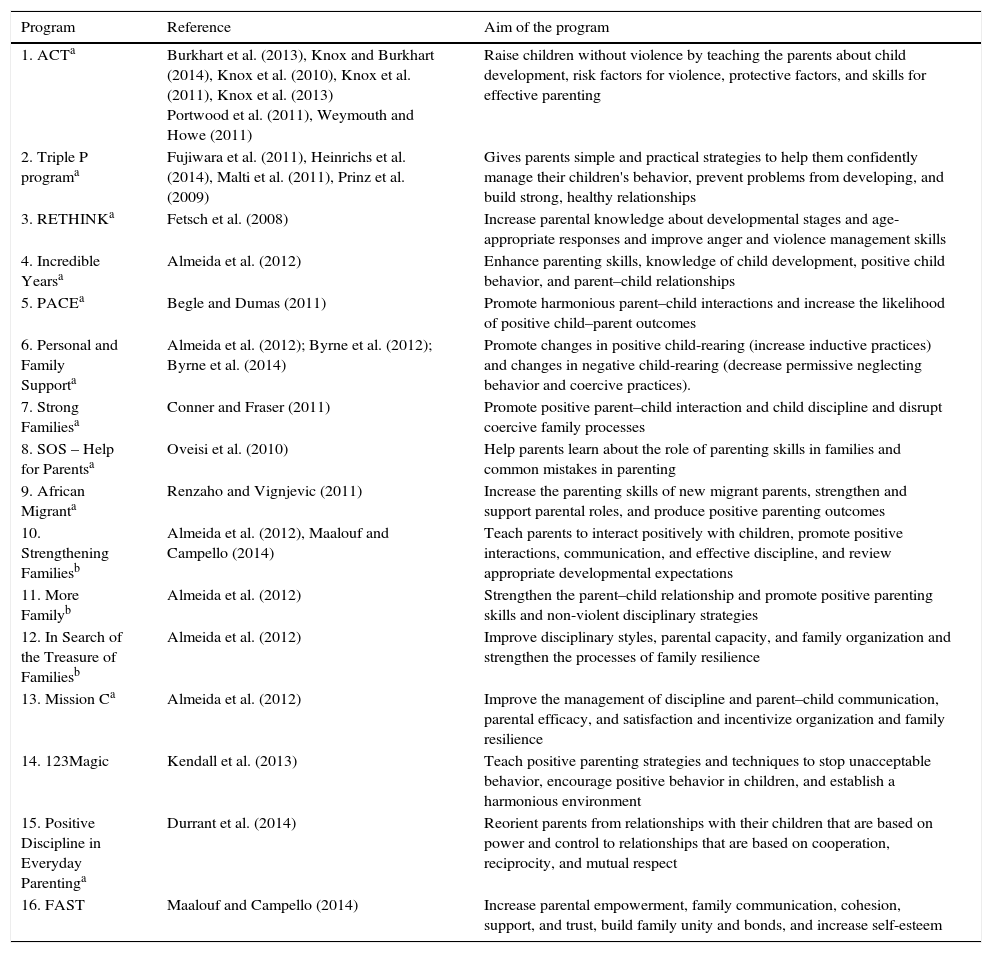

Types of parenting educational programsThe 23 studies reported 16 different types of parenting educational programs to prevent violence and maltreatment against children that were developed using group-based interventions (Table 1). The programs focused on the prevention of violence and maltreatment by promoting positive parenting practices and skills.

Parenting educational programs to prevent child violence and maltreatment: types and aims of the programs.

| Program | Reference | Aim of the program |

|---|---|---|

| 1. ACTa | Burkhart et al. (2013), Knox and Burkhart (2014), Knox et al. (2010), Knox et al. (2011), Knox et al. (2013) Portwood et al. (2011), Weymouth and Howe (2011) | Raise children without violence by teaching the parents about child development, risk factors for violence, protective factors, and skills for effective parenting |

| 2. Triple P programa | Fujiwara et al. (2011), Heinrichs et al. (2014), Malti et al. (2011), Prinz et al. (2009) | Gives parents simple and practical strategies to help them confidently manage their children's behavior, prevent problems from developing, and build strong, healthy relationships |

| 3. RETHINKa | Fetsch et al. (2008) | Increase parental knowledge about developmental stages and age-appropriate responses and improve anger and violence management skills |

| 4. Incredible Yearsa | Almeida et al. (2012) | Enhance parenting skills, knowledge of child development, positive child behavior, and parent–child relationships |

| 5. PACEa | Begle and Dumas (2011) | Promote harmonious parent–child interactions and increase the likelihood of positive child–parent outcomes |

| 6. Personal and Family Supporta | Almeida et al. (2012); Byrne et al. (2012); Byrne et al. (2014) | Promote changes in positive child-rearing (increase inductive practices) and changes in negative child-rearing (decrease permissive neglecting behavior and coercive practices). |

| 7. Strong Familiesa | Conner and Fraser (2011) | Promote positive parent–child interaction and child discipline and disrupt coercive family processes |

| 8. SOS – Help for Parentsa | Oveisi et al. (2010) | Help parents learn about the role of parenting skills in families and common mistakes in parenting |

| 9. African Migranta | Renzaho and Vignjevic (2011) | Increase the parenting skills of new migrant parents, strengthen and support parental roles, and produce positive parenting outcomes |

| 10. Strengthening Familiesb | Almeida et al. (2012), Maalouf and Campello (2014) | Teach parents to interact positively with children, promote positive interactions, communication, and effective discipline, and review appropriate developmental expectations |

| 11. More Familyb | Almeida et al. (2012) | Strengthen the parent–child relationship and promote positive parenting skills and non-violent disciplinary strategies |

| 12. In Search of the Treasure of Familiesb | Almeida et al. (2012) | Improve disciplinary styles, parental capacity, and family organization and strengthen the processes of family resilience |

| 13. Mission Ca | Almeida et al. (2012) | Improve the management of discipline and parent–child communication, parental efficacy, and satisfaction and incentivize organization and family resilience |

| 14. 123Magic | Kendall et al. (2013) | Teach positive parenting strategies and techniques to stop unacceptable behavior, encourage positive behavior in children, and establish a harmonious environment |

| 15. Positive Discipline in Everyday Parentinga | Durrant et al. (2014) | Reorient parents from relationships with their children that are based on power and control to relationships that are based on cooperation, reciprocity, and mutual respect |

| 16. FAST | Maalouf and Campello (2014) | Increase parental empowerment, family communication, cohesion, support, and trust, build family unity and bonds, and increase self-esteem |

The programs that were most frequently identified in the studies were the Adults and Children Together (ACT)-Raising Safe Kids program (n=7) and Positive Parenting Program (Triple P; n=4). Only one study analyzed the effectiveness of more than one parenting educational program together (Almeida et al., 2012). This study evaluated 56 parental education interventions, including programs with a flexible and structured format. The structured interventions included six programs: Incredible Years, Strengthening Families, Personal and Family Support Program, More Family, In Search of the Treasure of Families, and Mission C.

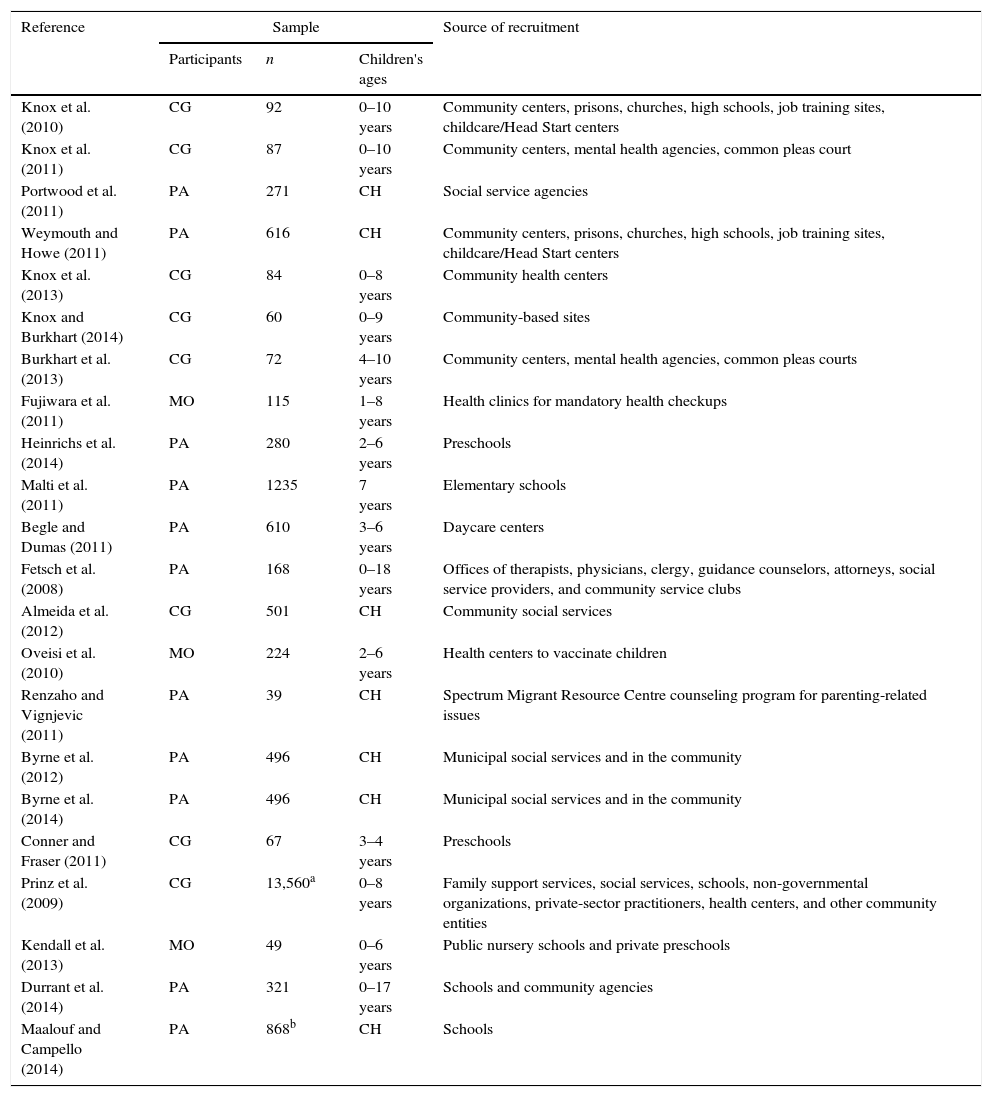

Table 2 shows that in 11 studies the participants were parents, including mothers and fathers (Begle & Dumas, 2011; Byrne et al., 2014; Byrne, Salmela-Aro, Read, & Rodrigo, 2012; Durrant et al., 2014; Fetsch, Yang, & Pettit, 2008; Heinrichs et al., 2014; Maalouf & Campello, 2014; Malti, Ribeaud, & Eisner, 2011; Portwood, Lambert, Abrams, & Nelson, 2011; Renzaho & Vignjevic, 2011; Weymouth & Howe, 2011). The parenting program was conducted with caregivers, including mothers, fathers, and other family members, in nine studies (Almeida et al., 2012; Burkhart, Knox, & Brockmyer, 2013; Conner & Fraser, 2011; Knox, Burkhart, & Cromly, 2013; Knox, Burkhart, & Howe, 2011; Knox, Burkhart, & Hunter, 2010; Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Marcynyszyn, Maher, & Corwin, 2011; Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker, 2009). Three of the preventive parenting programs focused only on mothers (Fujiwara, Kato, & Sanders, 2011; Kendall, Bloomfield, Appleton, & Kitaoka, 2013; Oveisi et al., 2010).

Parenting educational programs to prevent child violence and maltreatment: types, samples, and locations of implementation/recruitment.

| Reference | Sample | Source of recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | n | Children's ages | ||

| Knox et al. (2010) | CG | 92 | 0–10 years | Community centers, prisons, churches, high schools, job training sites, childcare/Head Start centers |

| Knox et al. (2011) | CG | 87 | 0–10 years | Community centers, mental health agencies, common pleas court |

| Portwood et al. (2011) | PA | 271 | CH | Social service agencies |

| Weymouth and Howe (2011) | PA | 616 | CH | Community centers, prisons, churches, high schools, job training sites, childcare/Head Start centers |

| Knox et al. (2013) | CG | 84 | 0–8 years | Community health centers |

| Knox and Burkhart (2014) | CG | 60 | 0–9 years | Community-based sites |

| Burkhart et al. (2013) | CG | 72 | 4–10 years | Community centers, mental health agencies, common pleas courts |

| Fujiwara et al. (2011) | MO | 115 | 1–8 years | Health clinics for mandatory health checkups |

| Heinrichs et al. (2014) | PA | 280 | 2–6 years | Preschools |

| Malti et al. (2011) | PA | 1235 | 7 years | Elementary schools |

| Begle and Dumas (2011) | PA | 610 | 3–6 years | Daycare centers |

| Fetsch et al. (2008) | PA | 168 | 0–18 years | Offices of therapists, physicians, clergy, guidance counselors, attorneys, social service providers, and community service clubs |

| Almeida et al. (2012) | CG | 501 | CH | Community social services |

| Oveisi et al. (2010) | MO | 224 | 2–6 years | Health centers to vaccinate children |

| Renzaho and Vignjevic (2011) | PA | 39 | CH | Spectrum Migrant Resource Centre counseling program for parenting-related issues |

| Byrne et al. (2012) | PA | 496 | CH | Municipal social services and in the community |

| Byrne et al. (2014) | PA | 496 | CH | Municipal social services and in the community |

| Conner and Fraser (2011) | CG | 67 | 3–4 years | Preschools |

| Prinz et al. (2009) | CG | 13,560a | 0–8 years | Family support services, social services, schools, non-governmental organizations, private-sector practitioners, health centers, and other community entities |

| Kendall et al. (2013) | MO | 49 | 0–6 years | Public nursery schools and private preschools |

| Durrant et al. (2014) | PA | 321 | 0–17 years | Schools and community agencies |

| Maalouf and Campello (2014) | PA | 868b | CH | Schools |

CG, caregiver (parents and other family members); PA, parents; MO, mothers; n, number of participants in the study; CH, the article did not specify the age and only mentioned that the participants were parents of children.

The participants were recruited in different places, including community centers, schools, health centers, mental health agencies, daycare centers, social service agencies, child welfare agencies, prisons, common pleas courts, churches, job training sites, clergy offices, guidance counselor offices, attorney offices, family service organizations, and non-governmental organizations (Table 2).

Designs and methodologies of the studiesThe sample sizes presented a broad range in the studies reviewed herein (Table 2). Twenty-two articles had samples that ranged from 39 to 1235 participants (median=309). One study was conducted in 18 counties, and the estimated sample size was between 8883 and 13,560 families whose parents participated in the Triple P program (Prinz et al., 2009).

With regard to study design, only seven studies assessed the efficacy of the parenting educational programs (Table 3). Of these studies, six employed an RCT design (Conner & Fraser, 2011; Heinrichs et al., 2014; Knox et al., 2013; Malti et al., 2011; Oveisi et al., 2010; Portwood et al., 2011) with within- and between-group comparisons, and three included follow-up assessment (Heinrichs et al., 2014; Malti et al., 2011; Portwood et al., 2011). Only one study used a stratified random assignment of counties with within- and between-group comparisons (Prinz et al., 2009); this study was the first to randomize geographical areas.

Parenting educational programs, references, designs, outcome measures and instruments, main findings, and effectiveness/efficacy of the studies.

| Program | Reference | Design | Analysis | Outcomes, measures, and instruments | Main findings | Effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | Weymouth and Howe (2011) | Pre×Post | Within | • Parenting Instruments: ACT scale | • Parenting Pre<Post – Pro-social/Media violence literacy/Ages and stages knowledge/Violence prevention skills | Yesa |

| ACT | Knox and Burkhart (2014) | Pre×Post | Within | • Parenting Instrument: Parent Behavior Checklist, Parent-Child Tactics Scale | • Parenting Pre<Post – Nurturing behavior Pre>Post – Harsh parenting, negative discipline | Yesa |

| • Child behavior Instrument: Conduct Problems subscale of SDQ, Externalizing subscale of CBCL | • Child behavior Pre>Post – Child behavior problem | Yesa | ||||

| African Migrant | Renzaho and Vignjevic (2011) | Pre×Post | Within | • Parenting Instrument: AAPI-2 | • Parenting Pre<Post – Parental expectations/Parental empathy toward children's needs/Awareness and knowledge of alternatives to corporal punishment/Parent–child family roles | Yesa |

| Personal Family Support | Byrne et al. (2012) | Pre×Post | Within | • Parenting Instrument: Situational Questionnaire on Child-Rearing Practices | • Parenting Pre<Post – Inductive parenting Pre>Post – Coercive and permissive-neglecting parenting | Yesa |

| Personal Family Support | Byrne et al. (2014) | Pre×Post×Follow-up | • Parenting Instrument: Parental Questionnaire in Child Development and Education, Parental Questionnaire on Parental Agency, Situational Questionnaire on Childrearing Risk Practices | • Parenting Pre>Post – Parents’ support of simplistic (nurturism), passive (nativism), and mechanistic (environmentalism) views of child development/Permissive-neglectful and coercive practices Pre<Post – Inductive practice/Parental internal control | Yesa | |

| Set of interventions | Almeida et al. (2012) | Pre×Post | Within | • Parenting Instrument: Parenting Stress Index | • Parenting Pre>Post – Parental stress Pre<Post – Empathy/Corporal Punishment/Role Reversal | Yesa |

| • Child behavior Instrument: SDQ | • Child behavior Pre>Post – Child behavior and emotional difficulties | Yesa | ||||

| • Social support Instrument: Family Social Support Network Function Scale, Personal and Social Support Scale | • Social support Pre>Post – Absence of support Pre<Post – Perception of support | Yesa | ||||

| Positive Discipline Everyday Parenting | Durrant et al. (2014) | Pre×Post | • Parenting Instrument: questionnaires constructed for the research | • Parenting Pre>Post – Approval of physical punishment/Subjective norms about parent–child conflict Pre<Post – Self-efficacy | Yesa | |

| 123Magic | Kendall et al. (2013) | Pre×Post×Follow-up (3 months) | Within | • Parenting Instrument: Parenting Self-Efficacy, Parenting Stress Index-Short Form | • Parenting Pre<Post<Follow-up – Parenting self-efficacy/Emotion and affection/Play and enjoyment/Empathy and understanding/Control/Discipline and setting boundaries/Pressure/Self-acceptance/Learning and knowledge Pre>Follow-up – Parental stress/Difficult child | Yesa |

| RETHINK | Fetsch et al. (2008) | Post×Follow-up (2.5 months) | Within | • Family conflict Instrument: Conflict Tactics Scale-Form, Bloom's Family Conflict subscale | • Family conflict Post<Follow-up – Verbal reasoning-self/Verbal reasoning-other Post>Follow-up – Verbal aggression-self/Physical aggression-self/Verbal aggression-other/Physical aggression-other/Bloom's Family Conflict measure | Yesa |

| • Anger Instrument: State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory | • Anger Post<Follow-up – Anger control Post>Follow-up – Trait anger/Angry temperament/Angry reaction/Anger-in/Anger-out/Anger expression | Yesa | ||||

| Strengthening Families and FAST | Maalouf and Campello (2014) | Pre×Post | • Parenting Instrument: violence indicators questionnaire collected from the children, Family Environment Scale (conflict subscale) | • Parenting Pre<Post – Solve problems together/Parents are calm when disciplining/Children feel that their parents love and respect them Pre>Post – Conflict subscale | Yesa | |

| • Anger Instrument: questionnaire about anger management | • Anger Pre<Post – Anger management | Yesa | ||||

| • Child behavior Instrument: SDQ (conduct pro | • Child behavior Pre>Post – Conduct problems | Yesa | ||||

| ACT | Knox et al. (2010) | GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: ACT scale, questionnaire on harsh discipline | • Parenting GI Pre<Post – ACT total score/Hostile Parenting and Social Skills (subscale) GI Pre>Post – Spanking and hitting with objects | Yesa |

| ACT | Knox et al. (2011) | GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Child behavior Instrument: SDQ, Externalizing subscale of CBCL | • Child behavior GI Pre>Post – SDQ Conduct problems | Yesa |

| • Child behavior Pre>Post – Externalizing problems (GI and GC) | No | |||||

| ACT | Burkhart et al. (2013) | GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Child behavior Instrument: Early Childhood Bullying Questionnaire | • Child behavior GI Pre>Post – Child bullying | Yesa |

| Triple P | Fujiwara et al. (2011) | GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: Parenting Scale, Parenting Experience Survey | • Parenting GI Pre>Post – Parenting Scale score/Laxness/Overreactive/Verbosity/Parenting is difficult/Parenting is stressful GI Pre<Post – Confidence in parenting/Pro-social | Yesa |

| • Child behavior Instrument: SDQ | • Child behavior GI Pre>Post – Conduct problems/Difficult behavior score/Hyperactivity | Yesa | ||||

| • Parent mental health Instrument: Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale | • Parent mental health GI Pre>Post – Total score/Depression scale | Yesa | ||||

| ACT | Portwood et al. (2011) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post×Follow-up (3 months) | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: Parent Behavior Checklist, Parenting Stress Index-Short Form | • Parenting GI Pre>Post and Pre>Follow-up – Harsh Discipline GI Pre<Post and Pre<Follow-up – Nurturing | Yesb |

| • Parenting GI Pre<Post and Pre<Follow-up – Parenting stress | No | |||||

| • Family conflict Instrument: Conflict Scale of the Family Environment | • Family conflict GI Pre=Post – No changes | No | ||||

| • Social support Instrument: Perceived Social Support | • Social support GI Pre<Post and GC Pre<Post – Perception of social support | No | ||||

| ACT | Knox et al. (2013) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: Parent Behavior Checklist, Parent-Child Tactics Scale, ACT Scale | • Parenting Post GI<GC – Psychological aggression/Physical assault/Nonviolent discipline Post GI>GC – Nurturing score/ACT score | Yesb |

| Triple P | Prinz et al. (2009) | RCT GI×GC | Within and between | • Child maltreatment Population indicators: child maltreatment recorded by child protective services, Child out-of-home placements, child hospitalizations and emergency room visits due to child maltreatment | • Child maltreatment Post GI<GC – Rates of substantiated child maltreatment cases, child out-of-home placements and hospitalizations, or emergency room visits due to child maltreatment injuries | Yesb |

| Triple P | Malti et al. (2011) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post×Follow-up (2 years) | Within and between | • Child behavior Instrument: Social Behavior Questionnaire (teachers, parents, and children evaluated) | • Child behavior GI Pre×Post×Follow-up and PATHS & Triple-P×PATHS – Not significant | No |

| Triple P | Heinrichs et al. (2014) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post×Follow-up (4 years) | • Parenting Instrument: Parenting Scale, Positive Parenting Questionnaire | • Parenting GI Pre>Post>Follow-up – Dysfunctional parenting Pre<Post<Follow-up – Warm parenting | Yesb | |

| • Child behavior Instrument: CBCL | • Child behavior GI Pre>Post – Child behavior problems | |||||

| SOS | Oveisi et al. (2010) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: Parenting Scale, questionnaire based on Parent-Child Conflict Tactics scale | • Parenting GI Pre>Post – Parenting scale/Parent–Child Conflict score (child abuse) | Yesb |

| Strong Families | Conner and Fraser (2011) | RCT GI×GC Pre×Post | Within and between | • Parenting Instrument: North Carolina Family Assessment Scale | • Parenting GI Pre>Post – Bonding/Supervision/Communication with child/Developmental expectations | Yesb |

| • Child behavior Instrument: North Carolina Family Assessment Scale, Berkeley Puppet Interview | • Child behavior GI Pre>Post – Academic competence/Social competence/Peer acceptance/Depression, anxiety/Aggression, hostility/Child behavior/School performance/Relationships with peers and caregivers GC Pre<Post – Aggression/Hostility | Yesb | ||||

| PACE | Begle and Dumas (2011) | GI Pre×Post×Follow-up (1 year) | Prediction | • Parenting Instruments: Parental Sense of Competence Scale, Parenting Stress Index-Short Form, Child Abuse Potential | • Parenting – Attendance Decreased rates of child abuse potential | Yesa |

| • Parent's quality of participation Increased parental satisfaction and decreased parental stress | ||||||

| • Child behavior Instrument: Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory-2, Coping Competence Scale | • Child behavior Active participation predicted increased child coping competence | Yesa |

Pre, pre-intervention; Post, post-intervention; GI, intervention group; GC, comparison group or control group; RCT, randomized controlled trial, AAPI-2, Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-version 2; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist.

The designs of 15 studies enabled evaluation of the effectiveness of the parenting educational programs. Of these studies, four used a clinical trial design with no randomization but with within- and between-group comparisons (Burkhart et al., 2013; Fujiwara et al., 2011; Knox et al., 2010, 2011). Additionally, 11 studies used only within-group comparisons with no control group (Almeida et al., 2012; Byrne et al., 2012, 2014; Durrant et al., 2014; Fetsch et al., 2008; Kendall et al., 2013; Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Maalouf & Campello, 2014; Marcynyszyn et al., 2011; Renzaho & Vignjevic, 2011; Weymouth & Howe, 2011). Three of these studies included follow-up assessment (Byrne et al., 2014; Fetsch et al., 2008; Kendall et al., 2013). Finally, only one study used a correlational design with pre- and post-intervention and follow-up (Begle & Dumas, 2011).

Main findings of the studiesThe efficacy/effectiveness of the parenting educational programs was evaluated through the following parent and child outcomes: (i) parent outcomes: parenting (e.g., parenting practices, parenting stress, parenting beliefs, and behaviors), parent anger management, parental mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety), perception of social support, and family conflict; (ii) child outcomes: child behavior. One study evaluated the program through population indicators of child maltreatment. The main findings of the studies were organized according to outcomes that were assessed both pre- and post-intervention (Table 3).

Parent outcomesParenting strategiesParenting strategies were the outcome that was assessed in most of the studies (n=18 [78%]). These studies found improvements in several areas that are related to effective parenting after participation in the parenting educational programs, such as the ACT program (Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Knox et al., 2010, 2013; Portwood et al., 2011; Weymouth & Howe, 2011), Triple P program (Fujiwara et al., 2011; Heinrichs et al., 2014), Incredible Years program (Marcynyszyn et al., 2011), African Migrant Parenting program (Renzaho & Vignjevic, 2011), APF-Personal and Family Support (Byrne et al., 2012, 2014), SOS (Oveisi et al., 2010), Strong Families (Conner & Fraser, 2011), PACE (Begle & Dumas, 2011), the set of interventions assessed by Almeida et al. (2012), 123Magic (Kendall et al., 2013), Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting program (Durrant et al., 2014), Strengthening the Families and Families (SFP), and Families and Schools Together (FAST; Maalouf & Campello, 2014).

The ACT program presented positive results in educating caregivers about non-violent parenting behavior and child development. These improvements included reductions of the use of harsh words, physical discipline (Portwood et al., 2011), spanking, and the rate of hitting children with objects (Knox et al., 2010), lower rates of psychologically and physically aggressive behavior toward children (Knox et al., 2013), and a decrease in harsh parenting and negative discipline (Knox & Burkhart, 2014). The results also showed improvements in knowledge of child development (Knox et al., 2010; Weymouth & Howe, 2011), behaviors and beliefs related to violence prevention (Knox et al., 2010), media violence literacy, anger management, pro-social problem solving (Weymouth & Howe, 2011), positive parenting behaviors (Knox et al., 2013), and nurturing behavior (Knox et al., 2013; Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Portwood et al., 2011). However, parents who participated in the ACT program reported an increase in parenting stress across time, perhaps because of being more attentive to the challenges associated with parenting (Portwood et al., 2011).

After participation in the Triple P program, the mothers effectively improved their parenting style and parental adjustment (Fujiwara et al., 2011). The Triple P intervention group reported significant reductions of dysfunctional parenting behavior and significant improvements in warm parenting from pre- to post-intervention, which was successfully maintained 4 years later (Heinrichs et al., 2014).

Participation in the Incredible Years program was associated with less parental distress, less defensive responding, less dysfunctional parent–child interactions, less child difficulty, less total stress, and greater empathy (Marcynyszyn et al., 2011). Exposure of the parents to the African Migrant Parenting Program was related to positive changes in parental expectations of the children, parental empathy toward the needs of children, and awareness and knowledge of alternatives to corporal punishment (Renzaho & Vignjevic, 2011).

After the APF-Personal and Family Support program, inductive parenting increased, and coercive and permissive-neglecting parenting decreased (Byrne et al., 2012). Parents after this intervention program also endorsed fewer negative and simplistic views about child development and education, reported that they had increased their utilization of reasoning and explanations to the child (i.e., inductive practice), were less likely to report physical punishment and verbal threats (i.e., coercive practice), and were less likely to disregard the child's needs or avoid correcting the child's misdeeds (i.e., permissive-neglectful practice; Byrne et al., 2014).

Parents who completed the SOS program exhibited significant reductions of physical and emotional abusive behavior and dysfunctional parenting practices from pre- to post-intervention, and these effects were maintained at 8-week follow-up (Oveisi et al., 2010). After the Strong Families program, the parents exhibited significantly greater improvements in bonding, supervision, communication with children, and developmental expectations than the comparison group.

The parents who actively participated in the PACE program exhibited an improvement in parental satisfaction and a decrease in parental stress (Begle & Dumas, 2011). Attendance in the program also predicted a decrease in potential child abuse at follow-up. The results for a subsample of parents at high-risk for child maltreatment were even stronger, in which engagement in the PACE program significantly improved almost all of the parental outcomes at post-intervention and follow-up (Begle & Dumas, 2011). The study that evaluated the set of interventions reported a reduction of parental stress and an improvement in parenting practices (i.e., empathic responding, a decrease in the use of punitive discipline, and the endorsement of parental roles) from pre- to post-intervention (Almeida et al., 2012). The participants in the 123Magic program also presented significant improvements in parenting stress and self-efficacy (Kendall et al., 2013). Parents who completed the Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting Program were less supportive of physical punishment, less likely to attribute typical child behaviors to “misbehavior” on the part of the child (e.g., defiance and disrespect), and more likely to believe that they have the skills that are necessary to be good parents from pre- to post-intervention (Durrant et al., 2014).

Significant changes in indicators of violence (reported by the children) from pre- to post-intervention were noted across all parental groups in the Strengthening the Families Program (Maalouf & Campello, 2014). These indicators were at different levels (e.g., feeling that parents really love and respect me, sitting with parents to solve problems together without shouting or getting angry, and feeling that parents are calm when they discipline the child). The post-intervention results of parents who completed the FAST program indicated a significant reduction of scores on the conflict subscales (Maalouf & Campello, 2014).

Qualitative data were also collected through focus groups (Kendall et al., 2013; Portwood et al., 2011). The parents perceived several benefits of the ACT program, such as controlling their anger, learning and implementing better parenting and discipline strategies, and recognizing when their child's behavior is developmentally appropriate (Portwood et al., 2011). The participants in the 123Magic program recognized changes in the way they behaved toward their child, felt they were now able to control their emotions, and also commented on the benefits of having the opportunity to listen to and share experiences with other parents (Kendall et al., 2013).

Other parent outcomesOther parent outcomes were a focus of the studies, such as the following: anger management, internal control, mental health, parents’ perception of social support, and family conflict. The RETHINK program focused on parents’ anger management, showing that parents controlled and managed their anger better at follow-up (an average of 2.5 months after the program) compared with the post-intervention phase (Fetsch et al., 2008). Parents who completed the Strengthening the Families Program reported that they were controlling and managing their own anger while dealing with the child better at the post-intervention assessment than at the pre-intervention assessment (Maalouf & Campello, 2014). After the APF intervention, the parents reported that they were more able to take control of their lives (i.e., internal control) by acting on everyday events with the potential goal of changing or keeping things the same (Byrne et al., 2014). The Triple P program effectively decreased parents’ mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and stress, assessed by the Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scales (Fujiwara et al., 2011).

Social support improved after the Incredible Years parenting educational program (Marcynyszyn et al., 2011) and after the set of parenting programs that were assessed by Almeida et al. (2012). Providing transportation for parents, supervision by practitioners, and structured interventions increased the parents’ perceptions of a social support network (Almeida et al., 2012). Furthermore, after the ACT program, both the intervention and comparison groups of parents exhibited a slight increase in social support from friends over time, with no change in social support from family (Portwood et al., 2011).

The RETHINK program effectively reduced family conflict at the 2.5-month follow-up (Fetsch et al., 2008). The ACT program produced no changes in family conflict that was perceived by parents; however, the program content did not focus on this variable (Portwood et al., 2011).

Child outcomesThe studies also evaluated the effectiveness/efficacy of the parenting educational programs with regard to changing child behavior (Almeida et al., 2012; Begle & Dumas, 2011; Burkhart et al., 2013; Conner & Fraser, 2011; Fujiwara et al., 2011; Heinrichs et al., 2014; Knox et al., 2011; Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Malti et al., 2011; Maalouf & Campello, 2014). Of these studies, nine (90%) effectively decreased child behavior problems after the parenting programs. These parenting programs were the following: Triple P (Fujiwara et al., 2011; Heinrichs et al., 2014), Strong Families (Conner & Fraser, 2011), PACE (Begle & Dumas, 2011), ACT Program (Burkhart et al., 2013; Knox & Burkhart, 2014; Knox et al., 2011), FAST (Maalouf & Campello, 2014), and the set of interventions that were assessed by Almeida et al. (2012).

Three studies evaluated the efficacy of the Triple P program on child behavior (Fujiwara et al., 2011; Heinrichs et al., 2014; Malti et al., 2011). One study measured child behavior using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997), showing that it effectively decreased child conduct problems (Fujiwara et al., 2011). Another study used the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Resorla, 2000) and found that the mothers in the intervention group reported immediate improvement in child behavior problems during the program; the mothers in the control group did not report this immediate improvement (Heinrichs et al., 2014). One study used the Social Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ; Tremblay et al., 1991) and found no significant effect on children's externalizing behavior (Malti et al., 2011). However, this measure had not been previously used in the country where the parenting educational program was implemented (Switzerland).

The Making Choices Program (for children), associated with the Strong Families Program (for parents), significantly reduced children's aggressive behavior compared with the control group (Conner & Fraser, 2011). Additionally, in this study, the children of parents in the intervention group presented greater improvements in behavior, school performance, and relationships with their caregivers and peers than the control group. This study used the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS; Kirk, Reed, & Lin, 1996) and Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI; Measelle, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 1998), which both have good internal consistency (Conner & Fraser, 2011).

The PACE program also effectively improved child outcomes. A higher quality of participation in the program predicted positive changes in child coping competence from pre-intervention to follow-up (Begle & Dumas, 2011). The outcomes were evaluated using the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory-2 (ECBI-2; Boggs, Eyberg, & Reynolds, 1990) and Coping Competence Scale (CCS_R; Moreland & Dumas, 2007), which both have good internal consistency (Begle & Dumas, 2011).

The effectiveness of the ACT program in improving child behavior was assessed using two different measures: Conduct Problems subscale of the SDQ and Externalizing subscale of the CBCL (Knox et al., 2011; Knox & Burkhart, 2014). One of these studies, which performed only within-group comparisons, showed that child behavior problems decreased, reflected by scores on the SDQ and CBCL, from pre- to post-intervention (Knox & Burkhart, 2014). The other study showed that the behavior of children in the ACT intervention group improved more than the comparison group, reflected by scores on the SDQ Conduct Problems subscale, from pre- to post-intervention. However, the CBCL Externalizing subscale indicated that children in both the treatment and comparison groups exhibited significant improvements in behavior over time (Knox et al., 2011). Additionally, another study showed that the ACT program effectively decreased bullying behavior in children, assessed by a questionnaire that was created based on items from the CBCL and SDQ (Burkhart et al., 2013).

After participating in the set of interventions that were assessed by Almeida et al. (2012), parents evaluated their children as showing fewer emotional, social, and behavioral problems. Furthermore, after the interventions, parents with more than 4 years of schooling reported fewer problems with their children than parents with a lower level of education (Almeida et al., 2012).

Parents who participated in the FAST program completed the Conduct Problems subscale of the SDQ to evaluate child behavior (Maalouf & Campello, 2014). The results of the study, which aggregated the results from five countries (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan), showed that the mean score on the Conduct Problems subscale decreased from pre- to post-intervention, showing improvements in children's behavior problems after the intervention (Maalouf & Campello, 2014).

Population database of child maltreatmentOne study analyzed the following three population indicators related to child maltreatment: (i) substantiated child maltreatment recorded by child protective services staff, (ii) child out-of-home placements recorded through the foster care system, and (iii) child hospitalizations and emergency room visits attributable to child maltreatment injuries (Prinz et al., 2009). The study reported differential and positive effects in the Triple P system counties, which had lower scores compared with control counties for the three population indicators. Therefore, preventive effects for all population indicators were found.

DiscussionThe findings of the present systematic review showed that the majority of the studies were conducted in developed countries, with only two studies in developing countries. These findings highlight the urgent call by the World Health Organization (2009) for further research on the applicability and effectiveness of child violence prevention programs in developing countries.

Some studies recruited participants from different locations (e.g., community centers, schools, and non-governmental organizations), whereas other studies enrolled participants from only one location. When studies recruit participants from different locations, variability and the degree of generalization increase because of the greater representativeness of the samples.

The parenting educational programs that were reviewed herein varied with regard to some of their characteristics, but the goals of the interventions were often similar, including: (i) increase parental knowledge about child development, (ii) promote effective parenting practices and skills, (iii) promote the use of non-violent parenting behaviors, and (iv) promote harmonious parent–child relationships. In addition to these general goals, the ACT program adds specific aspects of violence prevention, including the impact of violence and multiple methods for protecting children from violence in the home, community, and media (Knox et al., 2011). The present findings suggest that all of these strategies are important aspects of violence and maltreatment prevention that should be addressed in universal parenting programs.

The present review found that some of the studies did not seek to directly prevent violence and maltreatment but rather promote effective and positive parenting practices and consequently prevent child violence. These results are consistent with another review and a briefing from the World Health Organization (2009), which emphasized that the aims of many parenting programs are not specifically geared toward violence or maltreatment prevention; instead, they are designed to encourage healthy relationships, improve parental strategies, and decrease child behavior problems. Therefore, violence is seldom measured as an outcome, and the measures that were used in the studies are related to promoting effective parenting practices and changing child behavior (Holzer et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2009). Some of the studies evaluated parenting strategies, including specific practices that are related to violence and maltreatment (e.g., violence prevention skills, awareness and knowledge of alternatives to corporal punishment, spanking and hitting with objects, and harsh discipline). Additionally, one study reported lower scores on population indicators of child maltreatment in counties that participated in the Triple P program. The results of these studies suggest possible relationships between effective parenting practices and child maltreatment prevention.

The results of the studies reviewed herein encourage the implementation of parenting programs as a universal prevention strategy. All of the studies showed some improvements in effective parenting strategies post-intervention. Additionally, the programs effectively improved child behavior in 90% of the studies that assessed this outcome.

The studies that evaluated child behavior reported good psychometric properties of the instruments. Only one study showed that the program did not effectively improve child behavior problems (Malti et al., 2011). However, this study presented problems that were related to the measure of this outcome, which has not been previously used in the country where the parenting program was implemented. Thus, future studies should employ instruments with good psychometric qualities and a history of use in similar studies.

Other parent outcomes, such as the perception of social support, family conflict, mental health, anger management, and internal control, were also evaluated by some of the studies. The studies reported positive results that were related to the effectiveness of the programs in improving these outcomes. However, more evidence is needed with regard to the effectiveness/efficacy of the parenting programs to improve these outcomes because few studies have performed such evaluations.

The present review found that only seven of the studies used an RCT design. Consequently, only these studies evaluated the efficacy of the parenting educational programs. This result shows that future studies should use sophisticated empirical methodologies, such as RCTs.

Considering the methodological CONSORT guidelines, a study with a rigorous methodological design should present a description of the trial design, sufficient details about the intervention to allow replication, and other aspects (e.g., randomization of the participants, power analysis to determine the proper sample size, blinding, and follow-up measures; Schulz, Altman, & Moher, 2010). None of studies reviewed herein mentioned power analysis to determine sample size. Only seven studies included a follow-up assessment; of these, only three were RCTs. The studies were based on self-report only, and no observational measures were included. Consistent with the World Health Organization (2009), the present review suggests that rigorous evaluations of prevention programs worldwide are necessary. Other suggestions for future studies are the utilization of the waiting list design. None of the studies reviewed herein used this design. In this design, the participants are randomly allocated to two groups, and all of the participants receive the intervention, with one group receiving immediate intervention (intervention group) and the control group waiting to receive the intervention (delayed intervention). This design is appropriate when the study cannot be blinded and participation in the intervention is believed by the participants to be much more desirable than the control (Hulley, Cummings, Browner, Grady, & Newman, 2013). Furthermore, when institutions (e.g., communities, schools, and governments) decide that all members of a group should receive a specific intervention, randomization that precludes some individuals from receiving the intervention may be considered unethical, and randomization to a delayed intervention group may be considered acceptable (Hulley et al., 2013).

Some limitations of the present review should be mentioned. The literature searches had strict criteria of only including studies of universal preventive interventions. This focus was established because of the difficulty identifying child maltreatment within families, and this type of intervention is available to everyone within a population group. However, by excluding studies of at-risk populations, could be missed the opportunity to discuss valuable findings on the effectiveness of parenting programs in such populations. Also, to review the recent literature, the search period was restricted to 2008–2014. This period was established because previous reviews on violence and maltreatment prevention interventions covered articles that were published up to 2008. One other limitation was the inclusion of only face-to-face interventions and not interventions that were conducted via multimedia or the Internet. Overall, these limitations unlikely undermine the main findings of the present review.

Opportunities for future research on universal parenting programs can be identified. Future studies should address such relevant topics as the combination of child and parent outcomes, matching report and observation measures, the use of multiple informants or reporting measures (e.g., children, parents, relatives, and teachers), follow-up measures, and RCT designs.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The Foundation for Support of Research in the State of São Paulo, Brazil (FAPESP; grant #2012/25293-8) for ERP Altafim and the National Council of Science and Technology Development (CNPq) for MBM Linhares.