The issue of upgrading in global value chains has been treated in the literature, but there are still gaps to be filled in. One issue that still needs further investigation is the relation of business strategy and evolution of firms in global value chains, known as upgrading in the literature. In this paper, we have the objective of examining the occurrence and quality of upgrading in internationalized Information Technology firms of Brazilian origin. We employed the multiple case study method researching eight IT firms to study the issue. Different from what is expected, facts presented in the paper imply that although global value chains and upgrading are confirmed as useful concepts, not all the findings the literature presents converge with what this research brings. As for example, results do not converge with what was found in the literature for clothing. In other results, we confirmed what is in the literature, most notably, having the evolution in the chain blocked by clients and also competitive marginalization. Similar to any research, this one has limitations, which we list at the end of the manuscript.

Globalization processes, particularly from the 1980s decade onwards, intensified flows of people, capital, goods and information. In this new configuration, learning and the ability to innovate became key to competitiveness and growth of countries and firms (Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2011). To face the issues presented by this new world, the phenomenon of integrating countries and regions through international chains of production and trade was observed. The phenomenon has been recognized by the name of global value chains (Rugman & Verbeke, 2004).

The global value chain is understood as a set of inter-organizational networks, around a commodity or product, connecting families, firms and countries in the global economy (Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, 1994). Firms that connect to GVCs aim beyond profits: they search for competences, to develop more complex tasks with more added value. In the GVC literature, this event is known as upgrading (Gereffi, 1999) and has been used to characterize the trajectory of going up in the value chain (Ponte & Ewert, 2009).

Upgrading can be understood as an action of performing high added value activities, as a result of using more sophisticated technologies, knowledge or competencies. Upgrading means the increase of benefits and or profits that come from participating in global value chains (Gereffi, 2013; Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, 1994). Upgrading is a strategic move to firms and can be of various forms.

Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) identified four types of upgrading that firms or groups of firms can achieve in GVCs. However, upgrading of firms connected to GVCs is neither easy nor does it happen naturally. In this regard, Ponte and Ewert (2009) note that product and process upgradings have coexisted with downgrading, higher risks and limited returns on capital, particularly in the more traditional export markets. Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) had already raised this issue when observing that upgrading has not been happening too often in developing country firms inserted in GVCs. In this context, upgrading is often constrained to low value added activities, mostly related to manufacturing (Navas-Alemán, 2011).

We focus the present paper on this discussion. First, it is recognized that upgrading does not occur automatically to developing country firms. Second, we link the event of upgrading to business strategy sophistication. Thus, the occurrence and quality of upgrading depend, among other things, on organizational choices, related to business strategy.

In the GVC literature, upgrading is treated in a functional way, without a link to business strategy and profits. In this paper, we aimed to address partially this perceived gap in the literature.

On the face of these arguments, the objective of the present paper is to analyze the occurrence and quality of upgrading in Brazilian origin Information Technology (IT) firms. We also intended to establish a connection between upgrading and business strategy.

The research used the multi-case study method. The eight studied firms were all in the IT industry and of Brazilian origin. Once observed upgrading, we investigated its quality using the typology proposed by Humphrey and Schmitz (2002).

It is expected that the result of the present paper can add to the knowledge of the field in terms of clarifying how upgrading occurs in high technology industries. Also, studying service firms is not common in global value chains. Finally, there is the empirical side of the research, throwing light on developing country firms upgrading. The perceived gap in the GVC literature we addressed, at least partially, is the link between GVC and business strategy.

Literature reviewUpgrading in global value chainsIn the last two decades, global value chains were recognized as an important phenomenon in terms of international trade (Backer & Miroudot, 2013; Baldwin, 2012; Cattaneo, Gereffi, Miroudot, & Taglioni, 2013). However, participating in global trade and markets require firms to learn continuously and, thus, perform new activities in the chains (Kadarusman & Nadvi, 2013; Kaplinsky & Morris, 2003). This move is known in the literature as upgrading.

Generically, upgrading is the event of firms moving up in the chain to perform more profitable activities. Usually it refers to less developed country firms, reacting to competition challenges (Gereffi, 2011; Gibbon & Ponte, 2005; Giuliani, Pietrobelli, & Rabellotti, 2005; Ponte & Ewert, 2009). Moving up in the value chain is desirable because it allows firms to appropriate a larger portion of the value added in the chains, maximizing the benefits (Cattaneo et al., 2013).

Gereffi (1999) introduced the concept of upgrading in the sense of organizational learning, to improve the position of firms and nations in international trade networks. Therefore, it is a dynamic move in the chain, characterized by the firm or country to occupy a more profitable and/or more sophisticated position, either in technology or more intensive in capital or competences (Barrientos, Gereffi, & Rossi, 2011; Cattaneo et al., 2013).

Complementarily, Gibbon and Ponte (2005) propose the term marginalization to refer to the opposite of upgrading. Marginalization occurs when a firm or a country is constrained to less profitable activities or market segments with low entry barriers. An extreme case of marginalization would be exclusion, a term used to designate the lack of capacity to enter GVCs, as well as being sacked from them.

What explains the choice of going to one route or another, upgrading or marginalization, is the ability to innovate and continuously develop new products and processes. Upgrading encompasses innovation and may be understood as the innovation to generate higher value added improving processes, products, functions in the chain and inter-sectorial migration (Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2004, 2011). Due to its characteristics, upgrading recognizes relative merits and the existence of rent.

According to Ponte and Ewert (2009), the mostly used upgrading classification in the literature is the one developed by Humphrey and Schmitz (2002). In this classification, upgrading is used to refer to four distinct changes that can be implemented by firms or groups of firms:

- I.

Process upgrading: transforming inputs into products more efficiently through reorganizing production or using superior technology.

- II.

Product upgrading: more sophisticated products, which can be defined by obtaining higher prices in the market.

- III.

Functional upgrading: performing new functions in the chain, as, for example, design or marketing.

- IV.

Inter-industry upgrading: firms can use the competency learned in a new industry.

While the first form means performing the activities more efficiently, the other three may lead to a repositioning of firms in global markets, because they start selling different products to a new profile of buyers.

Opportunities and challenges to upgrade in global value chainsValue chains focused on different market segments bring distinct opportunities (Gereffi & Lee, 2012; Giuliani et al., 2005; Navas-Alemán, 2011). Ponte and Ewert (2009) observe that process and product upgradings, as well as some functional moves, have coexisted with marginalization, higher risks and limited returns, most notably in traditional export markets.

Others, as Humphrey and Schmitz (2002), Humphrey (2003), Giuliani et al. (2005) and Ponte and Ewert (2009), alert to this issue when upgrading has not occurred to developing country firms in GVCs very often. In this regard, upgrading is very commonly constrained to low value added activities, mostly in production. Strategic activities, as innovation, are still concentrated in developed countries, usually headquarters (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002; Navas-Alemán, 2011; Schmitz, 1999).

When studying Brazilian firms in the Vale dos Sinos, Schmitz (1999) observed that in the beginning of the process, the Brazilian suppliers benefited from commercial liaisons and obtained higher gains with process upgrading. However, global buyers were not interested that their Brazilian suppliers upgraded in terms of better quality designs, branding and distribution channels, impeding their development.

A problem that may occur to firms searching to connect successfully to GVCs characterized by quasi-hierarchical relationships is being locked in this position (Humphrey, 2003; Navas-Alemán, 2011). Upgrading may result abandoning innovations by suppliers to accommodate buyer requirements and/or consumer buying pattern changes (Ponte & Ewert, 2009). In these circumstances, firms end up having their revenues coming from a small number of buyers and become specialized in one activity, usually production. Often, suppliers do not develop new abilities or allow them to wane due to relationship issues with the global buyer, becoming hostages of these clients.

In the case of developing countries as Brazil, the path to learning and upgrading in the chain may bring mixed characteristics, depending on the degree of explicit coordination and power asymmetries in the network (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005). The analysis of the dynamics of the relationship show that the supplier is held hostage of the relationship, by the buyer, who has invested in developing vendor's capabilities. To the buyer, it is not interesting to allow competitors benefit from its investment. From the supplier's perspective, it may be unprofitable to go after other buyers or market segments. This move may leave the supplier vulnerable to new forms of competition, usually developed by these global buyers.

These considerations suggest that the global chain may create or accelerate barriers to upgrading. In these circumstances, the first strategic goal to the firm should be avoiding being locked in relationships that may suffer from new forms of competition. The main strategic options against this locking are: (1) market diversification; (2) continuous search of excellence in production; (3) effective use of knowledge acquired in the chain (Cattaneo et al., 2013; Humphrey, 2003).

In order to overcome challenges and take advantage of opportunities, we observe that the ability to learn from demanding clients and leading users in services is the key to functional upgrading (Elfring & Baven, 1996; Navas-Alemán, 2011). The building of competences does not happen only within the firm. Competences that come from knowledge intensive services may be improved through outsourcing.

In the search for a critical path to upgrading in GVCs, Kaplinsky, Memedovic, Morris, and Readman (2003) propose it starts with processes, then products, both coming before functional upgrading. The last kind of upgrading to happen is inter-sectorial.

Steinfeld (2004) explains that in the past value chain coordination occurred internally in the vertically integrated firm. However, currently, there are opportunities to coordinate these chains beyond the limits of most firms. At least in a few industries, leading firms perform core activities in the value chain, as for example design or branding. There is the opportunity to organize effectively the rest of the chain in an effective way, without owning it. High risk and low return activities are transferred to others. Leading firms specialize according to their own sources of competitive advantage. Influence may be exerted through patented processes and exclusive designs.

In this regard, firms need to pursue strategies that aim at developing their learning processes and strengthen their abilities. Moreover, alliances and strategic partnerships, mergers and acquisitions may be used to drive this process, allowing firms to reach superior positions in the chain. This way, it is feasible to take advantage of global markets to upgrade in its several forms and dominate markets worldwide (Navas-Alemán, 2011).

Methodological aspectsThe paradigm used in this work is the phenomenological research, using qualitative and naturalistic approaches to understand human experience inductively and holistically in specific contexts (Patton, 1990). We chose the multiple case study method and used qualitative variables. This latest choice is anchored on the assertion that strategic variables are less measurable than the other ones. Most strategic variables can only be measured by their effects (Dunning, 1995).

The case study method may be the most appropriate method to assess complex organizational phenomena. Here, the instrumental case study is developed to provide insight into an issue. In this kind of study, the case plays a supportive role and facilitates our understanding of something (Stake, 1998). These are the main reasons for choosing this method in the present research.

Studied casesWe studied eight cases and assumed that each case was special. The first level of analysis captured the details of individual cases studied, and then, the cross-examination followed, depending on the individual analysis of the cases studied (Patton, 1990).

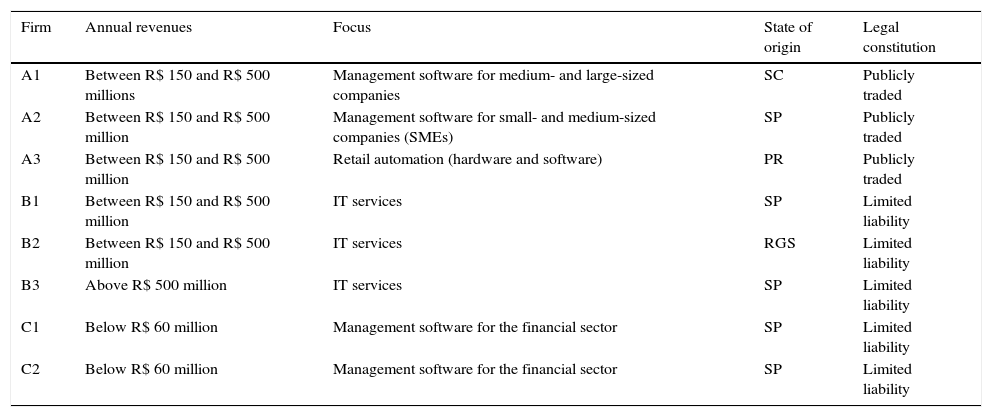

The profile of the studied cases may be examined in Table 1. All firms are involved in Information Technology activity, in the organizational segment (they sell their products to other firms). Firms A1, A2 and A3 are focused on software for management (Enterprise Resource Planning, ERP and others). Firm A3, as is focused on software for retail management, obtains an important chunk of its revenues from selling point of sale automation equipment. There is software embarked in these equipments, the revenues of which are included in the numbers released by the company. The firms named B1, B2 and B3 are service providers in Information Technology (IT). Firms B2 and B3, as is C1, are among the leaders in the activity in Brazil and are proceeding to be publicly traded in the Sao Paulo stock exchange (BM&FBOVESPA). C1, although much smaller in size than firms B2 and B3, already has among its shareholders a private equity investment fund and a state owned bank. B1 is part of a group of companies that is a reference in terms of innovative management and governance. Firms C1 and C2 are dedicated to management software for the financial sector.

Studied cases profile.

| Firm | Annual revenues | Focus | State of origin | Legal constitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Between R$ 150 and R$ 500 millions | Management software for medium- and large-sized companies | SC | Publicly traded |

| A2 | Between R$ 150 and R$ 500 million | Management software for small- and medium-sized companies (SMEs) | SP | Publicly traded |

| A3 | Between R$ 150 and R$ 500 million | Retail automation (hardware and software) | PR | Publicly traded |

| B1 | Between R$ 150 and R$ 500 million | IT services | SP | Limited liability |

| B2 | Between R$ 150 and R$ 500 million | IT services | RGS | Limited liability |

| B3 | Above R$ 500 million | IT services | SP | Limited liability |

| C1 | Below R$ 60 million | Management software for the financial sector | SP | Limited liability |

| C2 | Below R$ 60 million | Management software for the financial sector | SP | Limited liability |

Regarding the classification of studied firms, according to the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE] (2001), there is no convergence on the limits of business segments. For this research, the classification of firms by size is used, which is validated by the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES).

Thus, using BNDES (2008) criteria, two of the studied firms are classified as medium sized (C1 and C2, with revenues between R$ 10.5 and R$ 60 millions) and six as large sized (revenues above R$ 60 million). However, these classification criteria must be considered with caution. First, it must be so for the fact that there might be many differences between two organizations with revenues of, for example, R$ 65 million and R$ 700 million each one. Secondly, because firms C1 and C2, although small sized, according to data collected in the research are of significant size in the niche they operate. As the interviewed executives pointed, a firm with revenues of US$ 30 million in this segment may be considered relevant worldwide.

Procedures for result analysisThe case researcher digs into meanings, working to relate them to context and experience; in each instance, the work is reflective (Stake, 1998). Here, data analytics consisted of analysis, categorization and consolidation of case studies’ evidence. We used this logic to compare the empirical pattern observed with the expected standard. If there is a pattern of coincidence, the case study results reinforce the internal construct validity. To do the verification of standards, we made the categorization according to the type of upgrading proposed by Humphrey and Schmitz (2002): (1) Process upgrading; (2) Product upgrading; (3) Functional upgrading; and (4) Inter-sectorial upgrading.

As operational measure, we used the revenues of the studied firms in absolute terms and in a fashion that showed its recent growth. We used also a Liekert scale with six points (very low, low, discretely low, discretely high, high and very high).

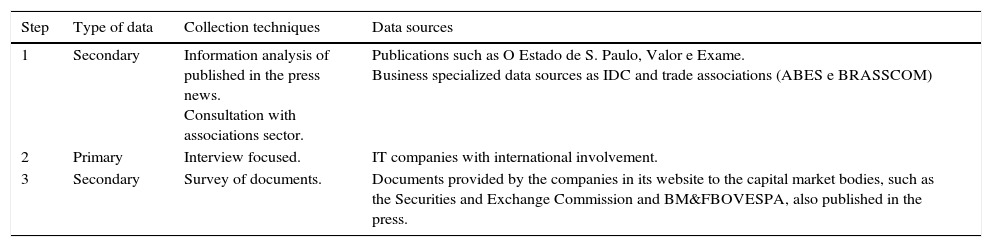

Data sourcesWe realized the primary data collection through interviews with executives from the eight companies selected for this research. The fieldwork took place in the first quarter of 2008. We did two collections of secondary data: first, before the field of research and second, in the results analysis phase. Table 2 contributes to a clear view of the sources to obtain information and techniques used in this study.

Sources of obtaining information and techniques used.

| Step | Type of data | Collection techniques | Data sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Secondary | Information analysis of published in the press news. Consultation with associations sector. | Publications such as O Estado de S. Paulo, Valor e Exame. Business specialized data sources as IDC and trade associations (ABES e BRASSCOM) |

| 2 | Primary | Interview focused. | IT companies with international involvement. |

| 3 | Secondary | Survey of documents. | Documents provided by the companies in its website to the capital market bodies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and BM&FBOVESPA, also published in the press. |

Schmitz and Knorringa (2000) recognize the subjectivity of the Liekert scale; however, its use is justified by the need of comparative assessments. Although we based the conclusions in more than one source of information, interviews performed a fundamental role in data collection. Interviews can be biased, even if they were neutral. The reason is that we examined the connection of the firms in the chains only from their own perspective, and because we did not consult other parties in the chain. As the qualitative researcher is interested in diversity of perceptions, the use of different sources to do a triangulation helps to clarify meaning, enriching the interpretation, providing different perspectives and helping the detection of contradictions (Stake, 1998).

ResultsIn line with the idea put by Humphrey and Schmitz (2002), firm C2 operates in a global chain that can be classified as quasi-hierarchy and its executives believe that this characteristic has helped in achieving product upgrading. In truth, when short term is considered, C2 executives believe that it is not feasible to evolve to other functions in the chain. In the case of firms B2 and B3, these are connected to global chains lead by buyers. Firm B3 executives mentioned with emphasis the migration to more sophisticated products. Firm B2, considered the investment in a software development center in Mexico, seems to be performing more sophisticated functions in the chain. Firm B1 executives look very conscious to the limits of upgrading by the company; it was asserted that they know how fragile the relationship with the leader of the chain is. Although in this case the firm operates in a chain, that among the studied firms is the closest to what is considered in the literature as a network, lead by a US company. In relation to the support of local institutions, besides Brazilian government incentives through BNDES and Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP, government agency linked to the Science and Technology Ministry), the studied firms invest in upgrading.

With the concepts of Kaplinsky and Morris (2003) and Gibbon and Ponte (2005), we considered that upgrading has occurred in firms A3, B1 and B3. Firm A3 changed its role in the chain, because earlier it was limited to supplying hardware and it added software to its offer. About being a function that brings higher rents, we cannot assert this yet because the firm is still implementing its management procedures to the software operations it bought. In the case of firm B1, it aims to evolve permanently to higher rent roles, which means to “prepare to the next technological wave”, as defined by the executive that was interviewed in this company. Many a times, this search means connecting to another value chain. Firm B3 executives see clearly what functions in the chain bring high rents. B3 makes the effort to evolve to the high rent roles. In this studied case, low rent jobs are used to block competitors and to start a relationship with new clients aiming to evolve to the high rent ones.

As Gibbon and Ponte (2005) put forth, cases B2 and B3 need to pay attention to marginalization. Firm B3 mentioned the effort in the direction of avoiding marginalization explicitly and spontaneously. One firm that seems to avoid marginalization is B1. It is worth to say that the firm has been successfully achieving it for a few years.

In terms of learning and upgrading, as argued by Kaplinsky and Morris (2003), follows a profile of the studied cases in this regard:

The organizational change implemented in 1999 and in the years that followed by firm A1 is something that deserves notice in terms of learning.

In the case of firm A3, upgrading occurred when it added software to its offer. Learning happened as well with product development abroad – manufacturing in China to the United States (US) market – and with adding third parties’ products, with the firm's brand to its sales catalog.

Firm B1 executives consider learning as its operational standard. The company changed its focus several times in the past and prepares itself to change again in the future. In the case of firm B3, it has put effort in migrating to more sophisticated products that bring high rents. In terms of learning and change, the interviewed executives’ assessment is that the company structure is used to frequent change.

Firm A1 also mentioned explicitly the effort to move to more sophisticated areas, where high rents can be obtained. The dynamism that exists in the activity was also mentioned, because high rent activities are always changing. If a firm stands still, it will be transferred to low complexity and rent market segments.

In relation to the ideas of Kaplinsky and Morris (2003), we found that in one of the studied cases, executives are aware that high rent activities are the ones close to the client core business. In terms of uniqueness, studied firms are aware of its importance. However, it was mentioned many times that obtaining and maintaining technological uniqueness is difficult. Firms B2 and B3 asserted that it is difficult to build entry barriers. One barrier these firms built is related to scale. Cases A1 and A2 developed entry barriers related to their distribution channels.

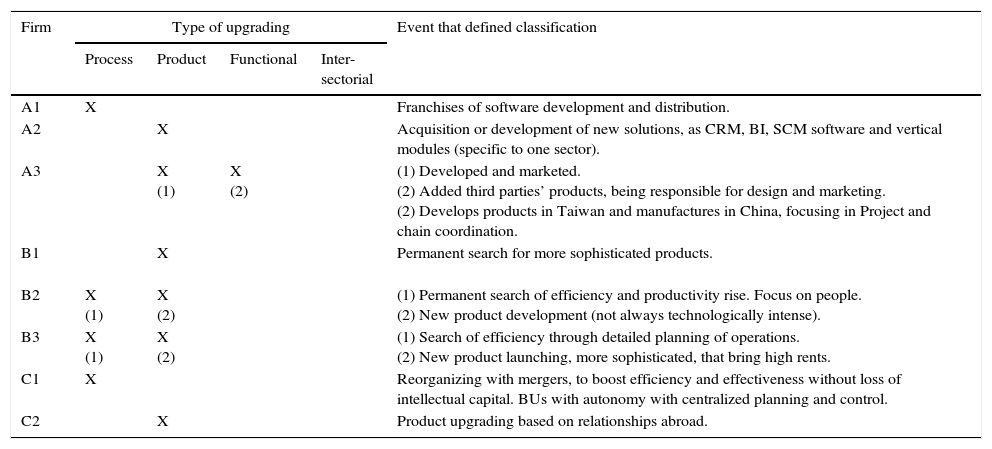

In relation to types of upgrading, Table 3 shows what we verified in the research.

Classification of studied cases regarding upgrading.

| Firm | Type of upgrading | Event that defined classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Product | Functional | Inter-sectorial | ||

| A1 | X | Franchises of software development and distribution. | |||

| A2 | X | Acquisition or development of new solutions, as CRM, BI, SCM software and vertical modules (specific to one sector). | |||

| A3 | X (1) | X (2) | (1) Developed and marketed. (2) Added third parties’ products, being responsible for design and marketing. (2) Develops products in Taiwan and manufactures in China, focusing in Project and chain coordination. | ||

| B1 | X | Permanent search for more sophisticated products. | |||

| B2 | X (1) | X (2) | (1) Permanent search of efficiency and productivity rise. Focus on people. (2) New product development (not always technologically intense). | ||

| B3 | X (1) | X (2) | (1) Search of efficiency through detailed planning of operations. (2) New product launching, more sophisticated, that bring high rents. | ||

| C1 | X | Reorganizing with mergers, to boost efficiency and effectiveness without loss of intellectual capital. BUs with autonomy with centralized planning and control. | |||

| C2 | X | Product upgrading based on relationships abroad. | |||

However, there is criticism on the emphasis of Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) on functional upgrading (Gibbon & Ponte, 2005); this event was observed only in the case of firm B3. This company seems to be the leader of the chain it is connected to. Although the chain looks to be the same for hardware and for commercial automation software, the firm has not resigned its previous roles. The company has diminished the intensity of the involvement in its previous roles, but we cannot consider it negative, because new roles are more sophisticated than the previous ones. Regarding this kind of upgrading being superior, if we had used the market value measurement, this firm, as aired by the press in Brazil, has not succeeded, its capitalization since the Initial Public Offering (IPO) has decreased at least 50%.

We observed that in many of the studied cases there is a combination of high and low paths to competitiveness. However, upgrading is not limited to production, even in the cases where products are less differentiated (firms B2 and B3) (Schmitz, 1999). In all firms studied, we registered frequent mention of roles that bring high rewards. However, in any of the studied firms, we observed orientation to exports. All the studied firms started out due to the existence of a sophisticated internal market in Brazil (Humphrey, 2003).

In relation to the hurdles and drivers of upgrading, we observed the presence of some of the examples of Kaplinsky and Morris (2003), as follows:

Hurdles- –

Resistance of managerial levels to change. In the case of firm B3, where constant revisions of structure have occurred, this has not been observed. The comment is that executives are already used to constant changes.

- –

In terms of shortage of enough qualified people in Brazil to the IT sector, evidence that it may exist is seen by the creation of a university for employee and partner in firm A3.

- –

Another hurdle mentioned, in this case external to the firm, is the fact that Brazil has not yet signed international agreements of intellectual property.

- –

Especially in the case of firm B1, it calls attention to the issue of structured processes aiming at permanent development.

- –

Several of the executives interviewed noted the surge in labor costs which is already in levels that were classified as high.

- –

Competition in the Brazilian market has been increasing, with the entrance of companies from India (mentioned by firm B3) being noted.

The surge in labor costs works as a driver because it acts as a incentive for the development of more sophisticated products by the studied firms and puts pressure on them to look for activities that yield high rents.

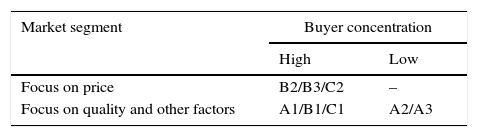

We noted the focus on competing with price, especially in the case of firms B2, B3 and C1. In the cases B2 and B3, there is emphasis on process upgrading (production). The issue of conflict of interest was mentioned only by firm B1. In this case, differently of what is mentioned by Schmitz (1999), the firm abroad is not the buyer, but the one who manages the chain in which the studied firm is connected to. The issue of blocking the learning by the studied firm happened in other circumstances for firm B1. The leader of the chain at the time, a US origin company, blocked the learning by the studied firm. In regard of buying segment concentration, what could work as a hurdle to functional upgrading, we observed it in the cases of firms A1, B1, B2, B3, C1 and C2. Firm C2, in the product electronic management of documents, could act to depend less on a concentrated buying segment; however, there is high probability of coincidence with the buying segment of the financial product, which is highly concentrated. In truth, in the case if functional upgrading occurred, the buying base is fragmented, composed of small enterprises, in its majority. It was aired in the press that this firm had problems when it got involved with large firms to market one of its products.

Different to what was found by Bazan and Navas-Alemán (2001), we did not observe the issue of upgrading discretely. The studied firms look actively for market diversification. The studied firm that takes part in several chains is A3. In this case, we noted different trajectories in the chains. In the hardware chain, this firm has evolved more than in the software chain. The software issue is recognized as a challenge, in markets abroad as well. In all the cases, there is a strong will to learn from international clients and partners, thus being different from what was concluded by Schmitz and Knorringa (2000).

In terms of the conclusion of Elfring and Baven (1996) about the link between learning from demanding buyers and functional upgrading, the only case that can be discussed is A3. In this case, functional upgrading does not seem to have come from demanding buyers, but from the need to build entry barriers to competitors, complementing its commercial automation offer. Regarding the external development of competencies, what we found in the research is as follows:

- –

Occurs in case A2, with its franchises of development and distribution.

- –

Occurs in case A3, with product development in Asia and manufacturing in China.

- –

Occurs in case B1, with the modeling of the supply chain to the development of the offer to Latin America.

- –

It may occur also in case C1 with development in India.

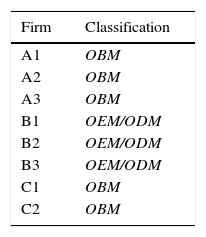

In relation to the existence of a sequence of upgrading in GVCs, the firms that most resemble OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) or ODMs (Original Design Manufacturers) are the ones that supply parts or products to other firms that put their brands on it. Firms B1, B2 and B3 can be classified as OEMs/ODMs. In firm B1, there is high level of knowledge in the activity, not only in technical terms, but also in terms of market intelligence and development of sophisticated financial operations, which may include government of countries. Firm B3, besides the recently opened facility, declared to operate with low differentiation products for strategic reasons. Firms A1, A2, A3, C1 and C2 developed or managed the development of its own products, selling them with their own brands. Thus, these firms can be classified as OBMs (Original Brand Manufacturers). It is important to point that firms A1, A3 and C1 use other firms as OEMs or ODMs. A brief summary of the studied cases regarding this aspect follows (Table 4).

Therefore, different from what is asserted in the literature about being the most common situation for developing country firms, the large majority of the studied firms develop their own brands. In the cases where it does not happen (B1, B2 and B3), low level international insertion is not a rule either.

Table 5 shows the determinants that Schmitz and Knorringa (2000) consider the most strategic and relevant to upgrading, and is applied to the studied cases.

Then, still with Schmitz and Knorringa (2000) approach, what should happen in the studied cases regarding upgrading and gains follows:

- –

Cases B2, B3 and C2: low level of upgrading and asymmetric gains.

- –

Cases A1, B1 and C1: High level of upgrading and asymmetric gains.

- –

Cases A2 and A3: High level of upgrading and balanced gains.

In terms of upgrading, cases B2 and B3 tend to confirm the literature. Firm B3 looks for high rent activities, thus trying to exit this class. The asymmetry of gains would be real, once these would be concentrated on buyers and system developers, the powerful partners of these firms. Firm C2 focuses on price; however perhaps, it would not be that necessary. It is possible that partners abroad are staying with part of this firm's potential gains.

Firms A1, B1 and C1 seem to confirm the high level of upgrading the literature prescribes to their situation. In the cases A1 and B1, asymmetry of gains looks favorable to both organizations. In the case C1, it is not possible to elaborate conclusions about this aspect.

Firms A2 and A3 seem to confirm the proposed classification in terms of upgrading. A2 has been acquiring other firms in a fast pace. A3 is the only one in the sample where we observed functional upgrading. In the case A2, gain asymmetry seems to exist toward the studied firm. In the case A3, the new activities the firm is performing in the chain have not yielded the expected results due to organizational reasons and issues related to technology, according to the interviewee. Thus, it is not possible to elaborate about gains in this latest case. In the case A2 there is something else that might be influencing the firm results positively; however, the financial statements of the studied firms have not been compared in this regard, according to the statements of the executives, and it may be concluded that this firm operates with higher fixed costs compared to its competitors. In the case of an increase in sales, the trend in this case is fixed costs absorption different from what will happen to competitors that have different proportions of fixed and variable costs.

It is not possible to assert that the results of this research converge with Gereffi's (1999) in clothing. The results obtained allow concluding that global insertion brings new references and opportunities to the studied cases. However, the case where functional upgrading occurred happened due to the local chain the firm is connected to. This firm is still in the process of operating with its complete offer abroad. Even in the local market, the process of expansion of its product scope happened with problems. Thus, evolution in the case is not a consequence of the export activity.

Regarding the issued posed by Humphrey and Schmitz (2002), we found upgrade in production in the cases of firms A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, C1 and C2. Thus, it can be considered that there is convergence with literature. Nothing can be concluded about the exclusion of other producers in general, although this was mentioned in the interviews with B2 and C2 executives. Firm B2, possibly due to lower prices. However, in case C2 the technology of the Brazilian origin company was, at the time, superior of what buyers specified. Buyer succession occurred in the case B3. However, the international insertion of this firm can be classified as very timid. It seems to be a planned effort of the studied firm and not something related to buyers developing their supplier.

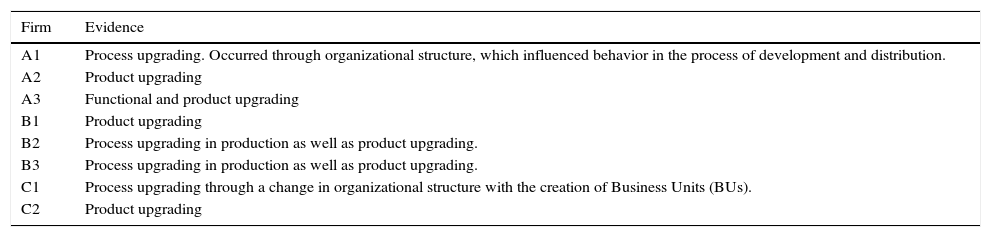

Different from what was found by Schmitz and Knorringa (2000), in this research we observed evidence of upgrading beyond production (Table 6).

Evidence of upgrading beyond production.

| Firm | Evidence |

|---|---|

| A1 | Process upgrading. Occurred through organizational structure, which influenced behavior in the process of development and distribution. |

| A2 | Product upgrading |

| A3 | Functional and product upgrading |

| B1 | Product upgrading |

| B2 | Process upgrading in production as well as product upgrading. |

| B3 | Process upgrading in production as well as product upgrading. |

| C1 | Process upgrading through a change in organizational structure with the creation of Business Units (BUs). |

| C2 | Product upgrading |

Thus, as can be concluded through the exam of information displayed in Table 6, upgrading occurred most of the times outside production. Only in the cases B2 and B3, it is possible to mention upgrading in production. However, in these two cases, we observed product upgrading as well. These cases are the two out of three where the chain is governed by the buyer. Thus, as noted by Schmitz and Knorringa (2000), the issue may be in the chain governance.

As noted by Bazan and Navas-Alemán (2004), process and product upgradings happen more often when compared to functional upgrading that we verified only in the case A3. However, in the case studied in this research, different from what was concluded about local chains in Brazil and about Latin American chains, we did not observe market governance locally and hybrid governance regionally. According to what we obtained in the interviews and evidence collected, we observed no differences between the local and the global chains. We found no cases where local chain is completely different from the global chain.

ConclusionThe analysis of the studied cases brought the following main results we present in the following paragraphs.

In the cases A2 and A3, we can assert that there is a common aspect: the focus on small and medium firms (SMEs). This market segment is more fragmented than the one composed by large organizations. Another characteristic of the SME business segment is that there is higher protection to competition than in the business segment composed by corporations. Firm A3 was the only one where functional upgrading occurred; however, different from what the literature indicates, this event has not occurred automatically: it is a case in which we classified the sophistication of firm strategy as being very high. Although we cannot assert it definitely, the relation between fragmentation of the SME segment and the occurrence of upgrading, evidence has been found suggesting attention be drawn to this point.

Among other important findings from this research, we can highlight that there were cases in which high risk and low return activities were transferred to third parties. This finding reinforces the argument of Steinfeld (2004). In one of the cases, we verified a situation of competitive marginalization or at least a tendency to this situation, as noted by Gibbon and Ponte (2005).

In the majority of the cases, we verified the possibility of being blocked in the position (Humphrey, 2003). The issue of blocking the learning by the studied firm happened when the leader of the chain blocked the evolution. It happened to be studied in firm B1. However, in respect to the buying segment concentration, we observed it in five of the cases (A1, B1, B2, B3, C1 and C2). This event could work as a hurdle to functional upgrading.

We found cases of upgrading outside production, different from what Schmitz and Knorringa (2000) found. However, only in two cases we noted upgrading in production. Furthermore, we also observed product upgrading in these two cases.

As limitations of this research, we can cite that the analysis of the actions of the studied firms, although examined by other means, depended in great part on what the interviewees declared and on the authors’ judgments. There are potential problems that might arise from these circumstances, as dissimulated answers, emphasis on politically correct actions and hiding strategies and future plans of the firms. The last situation certainly happened.

Although the studied firms share many things in common, the quality of the comparison of the cases depends on sample homogeneity. Complete homogeneity is not probable. There are differences that must be observed, for example, the size of the studied firms, once there is not a unique rule in this regard in Brazil; and the legal form of the firms, because three of the companies are publicly traded and other three are being prepared to go public.

The technical issues of the studied cases are not examined in this study. The research concentrated on management aspects, specifically business strategy and connection to GVCs. Although technical aspects are recognized as relevant, as they can alter the trajectory of a business of the profile of the studied firms, they are outside the scope of this investigation.

Finally, as we analyzed only the firms from the selected cases; we suggest that other firms in the chains should be studied in order to obtain more robust conclusions about GVCs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.