The low-income market has become the focus of many companies since the economic growth of emerging countries has been highlighted nationally and internationally. Thus, the development of innovations for this segment has also become a central issue in academia and management. Literature on disruptive innovation presents assumptions that justify its analysis in light of the low-income market. Thus, this article analyzes the concept of disruptive innovation in this market. For this purpose, the article is divided into two parts: the first focuses on a theoretical review of disruptive innovation, whilst the second presents a review of national publications dealing with this concept. The national literature review shows that few studies have been concerned with addressing these concepts in Business Administration and Marketing, especially considering aspects of the low-income context.

The need for business growth combined with global integration strategies reflects potential interest in low-income classes, known internationally as the bottom of the pyramid (BOP). In this sense, the Brazilian market presents many opportunities (Barki & Parente, 2010; Nogami, Vieira, & Medeiros, 2012). Moreover, due to the varied needs encountered in emerging markets, companies are expected to develop low-cost innovative solutions (Prahalad, 2012; Viswanathan, Jung, Venugopal, Minefee, & Jung, 2014). Thus, this article situates the low-income market and its nuances in the context of innovation.

The BOP market includes four billion people who have income, information, and infrastructure restrictions (Prahalad, 2005). These people are predominantly located in Asia, Africa, and South America, although in North America and Europe there are also people in such conditions (Kaplinsky et al., 2009). Due to conflicting classifications and nomenclatures that satisfy different contexts (Nogami & Pacagnan, 2011), this article considers the BOP as this large contingent of four billion people around the world.

Innovations in low-income markets do not follow traditional formats (Govindarajan & Trimble, 2013). Cutting-edge technologies and the development of next-generation products require environmental conditions that are not disseminated to the entire population of countries considered as emerging (such as Brazil). In addition, low-income consumers are quite heterogeneous, even within a particular region. When extrapolating their characteristics in different countries, variability is even more pronounced (Hall, Matos, & Martin, 2014).

The BOP market presents different challenges for the development, dissemination, and adoption of innovation, since it has different constraints (Nakata & Weidner, 2012). One is a lack of income to purchase innovative solutions through products and services, considering that the most basic needs of food, housing, and health must to be satisfied and practically comprise all household income (Silva, Parente, & Kato, 2009). Innovative products with high technology tend not to be a priority for low-income consumers (Viswanathan & Sridharan, 2012), except when the need for social recognition and status is highly valued by the individual. These exceptions are more often observed in the middle class.

In addition to having a low income, budget instability also jeopardizes financial planning. Often, people in this category do part-time jobs aside from their main job to supplement income. However, being unstable means that these jobs become a constraint to long-term planning and financial security (Parente, Limeira, & Barki, 2008).

Another constraint is a lack of information and knowledge. Restricted internet access and difficulty in reading more formal texts can limit consumer information (Abdelnour & Branzei, 2010; Viswanathan, 2016). Consequently, the low-income consumer is devoid of knowledge about technology (Hang, Chen, & Subramian, 2010). In many cases technology products require prior and advanced knowledge about their features and accessories. A lack of information and knowledge consequently generates a lack of confidence, which is essential for consumers when adopting innovations (Viswanathan, Shultz, & Sridharan, 2014). Thus, these constraints are assumptions that should be considered when addressing the issue of BOP innovation.

The particular concept of innovation addressed in this article is disruptive innovation (Christensen, 1997, 2013). Although it has not been developed with a focus on the BOP, disruptive innovation has characteristics and premises adherent to the environment found in the low-income market. Considering increasing interest in research on low incomes and innovation, as well as highlighting the importance of (re)establishing epistemological limits about the definitions of the themes (Brem & Wolfram, 2014; Nogami & Pacagnan, 2011), this article seeks to fill a theoretical gap about the uses of the disruptive innovation concept in the context of the BOP, particularly in national publications.

Thus, this article introduces the concept of disruptive innovation within a contextual logic that involves the low-income market. The study is divided into two main parts: The first is a theoretical review of disruptive innovation and its synergistic characteristics in the low-income market; the second is a bibliographic review of national publications on the studied themes.

Disruptive innovationDeveloped in 1997, the concept of disruptive innovation has as a central significance in answering why large companies that seek innovation in traditional markets suffer from market myopia and are overtaken by new entrants that launch new and innovative solutions – that is, disruptive technology (Christensen, 1997, 2013). Disruptive technology can exist in products as well as in services and business models (Markides, 2006). Despite having been developed in an area of high technology (Southwest United States), this concept shows similarities with the contextual conditions of the BOP, since it basically relates lower technology to less-demanding consumers (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). To explain this phenomenon, the author separates the technologies into sustaining and disruptive.

Sustaining technology relates to radical or incremental improvements to established products that are valued by conventional consumers in main markets. Sustaining innovation entails progressive improvements, providing solutions to customers who require better performance (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). This innovation can be considered mainstream, and relates to the leading position of companies that are already at the top. A new company can hardly compete with large counterparts when using this type of innovation. For this reason, the concept of disruptive innovation is introduced (Christensen, 2013).

Disruptive technology is innovation in products, services, and business models that offer different solutions and alternatives to the market, and are mainly directed at non-traditional consumers. Disruptive innovation changes social practices and ways of living, working, and interacting (Christensen, 2001). In other words, it is not the technology itself that matters, but its use. These innovations are initially directed toward an audience that is different from that usually targeted by (“traditional”) sustaining innovations.

Disruptive innovation begins with meeting the needs of a less-demanding public and gradually gaining strength until it starts to meet the needs of more-demanding customers. It therefore becomes a threat to large companies that focus on sustaining innovations (Corsi & Di Minin, 2014). Disruptive innovation can be characterized as a new entrant in an existing market or as a driving force for the development of a new market (Markides, 2013).

Such innovation initially has lower performance compared to the main attributes of sustaining technologies. When technologies start to perform like sustaining technologies, they begin the disruption process, unsettling and threatening companies established in the market. Their main attributes include: being generally more convenient to use, having a lower prices, simplicity, reduced size, and being well positioned in the BOP market (Corsi & Di Minin, 2014; Yu & Hang, 2010).

It is assumed that disruptive innovations are primarily commercialized in emerging markets because their characteristics do not meet the expectation of traditional markets or upper-class customers (Baiyere, Haken, Westgeet, & Ratingen, 2011). Thus, Marketing should be more responsible for studying disruptive technologies than R&D areas. Identifying unmet needs and developing non-traditional solutions for customers are responsibilities assigned to Marketing. Disruptive innovation represents a solution to an unmet need.

Thus, sustaining innovation is directed to the top of the pyramid (TOP) and disruptive innovation is directed to the BOP (Rigby, Christensen, & Johnson, 2002; Ray & Ray, 2011). However, disruptive technology should be commercialized on a large scale to achieve profitability, like any other market that works with low profit margins. The essence of disruptive innovation is the ability to cause large companies established in developed markets to fail, which explains its name (Christensen, 1997; Corsi & Di Minin, 2014).

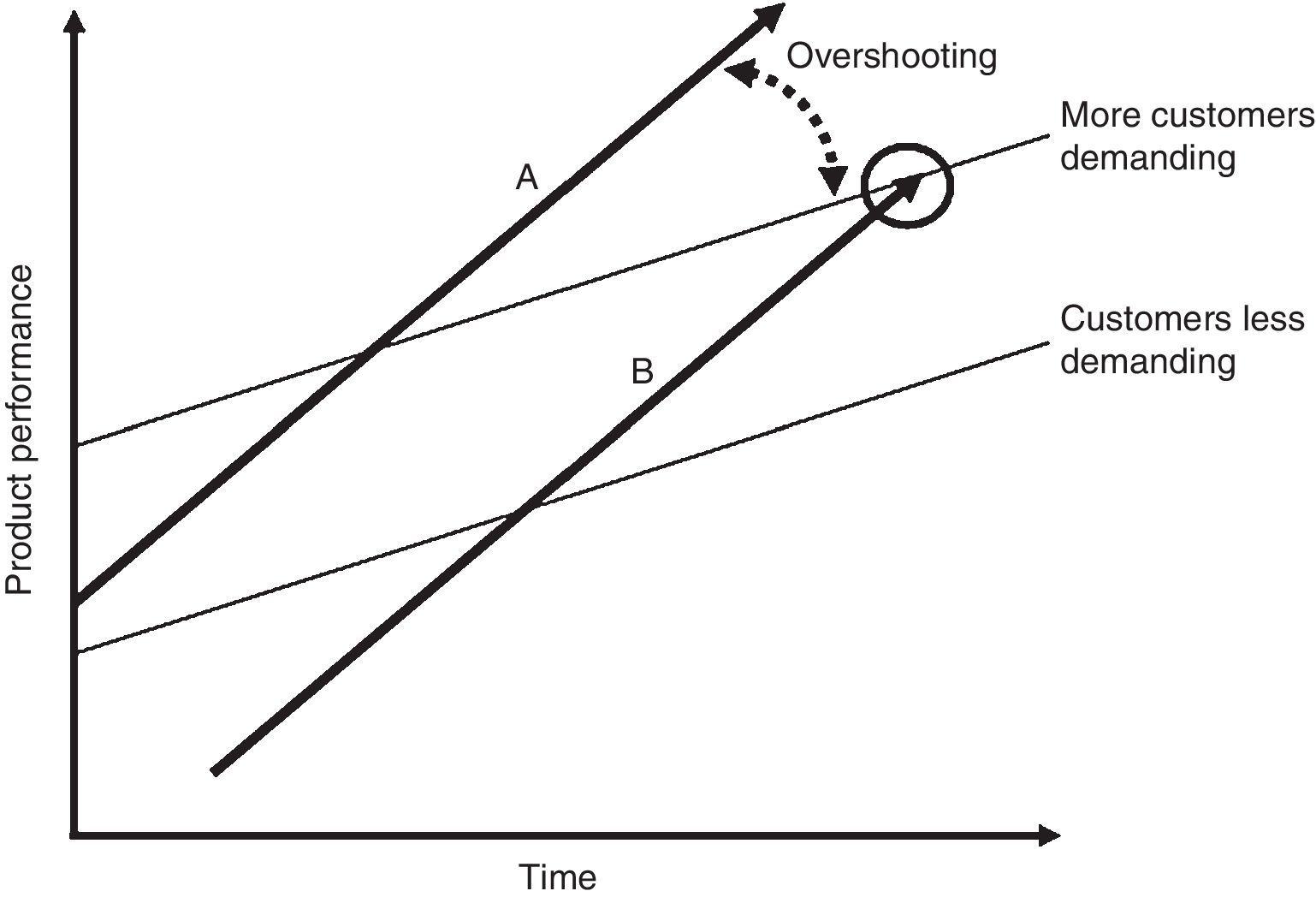

Fig. 1 maps the trajectory of disruptive innovation and sustaining innovation. Arrow A represents products, services, or business models with sustaining innovation (Christensen, 2001). To meet and exceed the expectations of more-demanding customers, companies need to invest time and money in R&D, which increase the price of their products. When arrow A crosses the line of more-demanding customers, it means innovation expectations have started to be overcome, beginning the overshooting phenomenon. This phenomenon is characterized by companies that have more technology than (even the most demanding) consumers can use, pay, or understand (Christensen & Raynor, 2003).

Disruptive innovation vs. sustaining innovation.

The level of technology and knowledge is high, making the price equally high – to a point where customers do not see enough value in the product to purchase and consume it (Christensen, 2013). This is common with electronics and computers. Thus, this phenomenon can be unfavorable because the pressure of market competitiveness that drives these increasingly advanced technologies – that even the more-demanding customers might not be able to absorb – can produce a negative image for the product (Christensen, 2013; Yu & Hang, 2010). Nevertheless, competitiveness among large companies transforms the search for more advanced technologies into a vicious cycle.

This situation allows other companies to enter the market by offering solutions with lower technology performance and consequently a lower price (Christensen, 2013). Arrow B represents the technology of these disruptive solutions, which initially meet the needs of less-demanding customers. They can expand their market share later on and also meet the needs of more-demanding customers by having products, services, and businesses with simpler attributes and lower prices (Christensen, 1997).

When arrow B meets the line of the less-demanding customers, the products, services, or new business model begins to be known and accepted in the market by these customers. By intensifying marketing activities, space and notoriety can be gained, leading to attention from other customers as well as competitors (Christensen, 1997; Corsi & Di Minin, 2014). The disruption process starts when arrow B crosses the line of the more-demanding customers, as the solutions start to compete with leading companies. At the moment emerging companies achieve market leadership – surpassing leading companies – disruption is considered complete. In some cases, disruption can lead large companies to bankruptcy – this is Christensen's (1997) argument.

Christensen's (1997) idea was not to show how to innovate in emerging markets and gain competitiveness among large companies; he wanted to indicate to large and established companies how they could go bankrupt if they do not watch competitors that have potential for fast growth – that is, the logic is inverted. The author was concerned about defending small and potential companies, but the goal here is also to point out that there is a way of growing in the market and competing with large and established companies, offering simple and cheap products to a segment that is still poorly explored (Yu & Hang, 2010). That is why the focus of disruptive innovation is on both technology and marketing. Specifically in marketing, analysis and consumption trends as well as concerns with individuals’ needs are key to boosting disruptive innovations. In other words, the crucial elements of disruptive innovation are found in the needs of less-demanding consumers, not so much in the technology itself.

The question Christensen wanted to answer was why leading companies are, in some cases, caught off guard and lose leadership to smaller companies with lower investment capability. This is another traditional concept with a prescriptive approach to companies (Corsi & Di Minin, 2014). The author points out that even though companies are apparently acting in the right way – that is, investing in innovation to offer the newest and best technology – they can still fail. It seems contradictory, but these bankruptcy cases occur precisely because companies seeking sustaining innovations are correctly managing their search for technology and more innovative products (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). The problem is overemphasizing technology and neglecting consumer needs.

Given the characteristics of disruptive innovation and consumer demands that disruptive innovation aims to fulfill, literature on this theme is appropriate to study the BOP market – although it has not been developed for this purpose (Baiyere & Roos, 2011; Zhou, Tong, & Li, 2011). The BOP customers are the main target of disruptive technology. However, innovation is not disruptive without business models changes. To be successful in the low-income market, is needed disruptive innovation in processes, supply chains, business model, consumer education, payment methods, and the people involved (Corsi & Di Minin, 2014).

Two assumptions are necessary for the realization of disruptive innovation in the low-income market: Disruptive innovation is not directed to the TOP, at least a priori; and the simplicity of disruptive solution attributes increases diffusion and adoption in the BOP market. These solutions must include low prices, simplicity, and convenience of use.

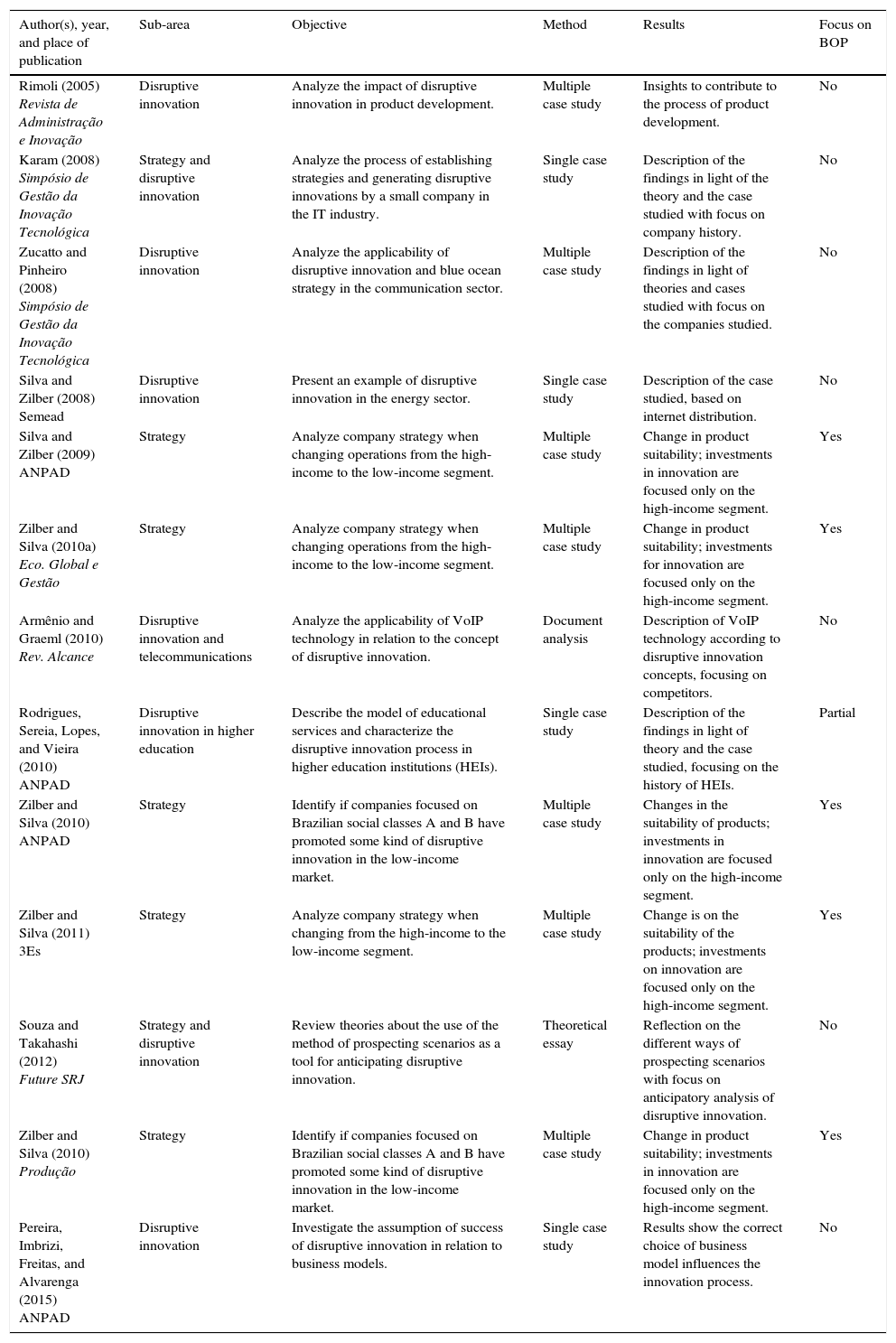

National publications on disruptive innovationBesides the theoretical review of the concept of disruptive innovation and its association with the low-income market, this article also presents an analysis of national publications on the subject. A search1 was carried out in the databases Spell (Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library), Google Scholar, Scielo (Scientific Eletronic Library Online), ANPAD (National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Education), and Semead (Business Administration Seminars). In addition to these, a search was also carried out directly on the websites of 22 journals ranked as A2 and B1 by the Qualis/CAPES system (the official evaluation system of Brazil's Ministry of Education), 4 specific journals on innovation, and 2 specific journals on marketing.2 Altogether, 13 articles on disruptive innovation were found. Table 1 shows a summary of the search performed.

Summary of national publications on disruptive innovation in Business Administration.

| Author(s), year, and place of publication | Sub-area | Objective | Method | Results | Focus on BOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rimoli (2005) Revista de Administração e Inovação | Disruptive innovation | Analyze the impact of disruptive innovation in product development. | Multiple case study | Insights to contribute to the process of product development. | No |

| Karam (2008) Simpósio de Gestão da Inovação Tecnológica | Strategy and disruptive innovation | Analyze the process of establishing strategies and generating disruptive innovations by a small company in the IT industry. | Single case study | Description of the findings in light of the theory and the case studied with focus on company history. | No |

| Zucatto and Pinheiro (2008) Simpósio de Gestão da Inovação Tecnológica | Disruptive innovation | Analyze the applicability of disruptive innovation and blue ocean strategy in the communication sector. | Multiple case study | Description of the findings in light of theories and cases studied with focus on the companies studied. | No |

| Silva and Zilber (2008) Semead | Disruptive innovation | Present an example of disruptive innovation in the energy sector. | Single case study | Description of the case studied, based on internet distribution. | No |

| Silva and Zilber (2009) ANPAD | Strategy | Analyze company strategy when changing operations from the high-income to the low-income segment. | Multiple case study | Change in product suitability; investments in innovation are focused only on the high-income segment. | Yes |

| Zilber and Silva (2010a) Eco. Global e Gestão | Strategy | Analyze company strategy when changing operations from the high-income to the low-income segment. | Multiple case study | Change in product suitability; investments for innovation are focused only on the high-income segment. | Yes |

| Armênio and Graeml (2010) Rev. Alcance | Disruptive innovation and telecommunications | Analyze the applicability of VoIP technology in relation to the concept of disruptive innovation. | Document analysis | Description of VoIP technology according to disruptive innovation concepts, focusing on competitors. | No |

| Rodrigues, Sereia, Lopes, and Vieira (2010) ANPAD | Disruptive innovation in higher education | Describe the model of educational services and characterize the disruptive innovation process in higher education institutions (HEIs). | Single case study | Description of the findings in light of theory and the case studied, focusing on the history of HEIs. | Partial |

| Zilber and Silva (2010) ANPAD | Strategy | Identify if companies focused on Brazilian social classes A and B have promoted some kind of disruptive innovation in the low-income market. | Multiple case study | Changes in the suitability of products; investments in innovation are focused only on the high-income segment. | Yes |

| Zilber and Silva (2011) 3Es | Strategy | Analyze company strategy when changing from the high-income to the low-income segment. | Multiple case study | Change is on the suitability of the products; investments on innovation are focused only on the high-income segment. | Yes |

| Souza and Takahashi (2012) Future SRJ | Strategy and disruptive innovation | Review theories about the use of the method of prospecting scenarios as a tool for anticipating disruptive innovation. | Theoretical essay | Reflection on the different ways of prospecting scenarios with focus on anticipatory analysis of disruptive innovation. | No |

| Zilber and Silva (2010) Produção | Strategy | Identify if companies focused on Brazilian social classes A and B have promoted some kind of disruptive innovation in the low-income market. | Multiple case study | Change in product suitability; investments in innovation are focused only on the high-income segment. | Yes |

| Pereira, Imbrizi, Freitas, and Alvarenga (2015) ANPAD | Disruptive innovation | Investigate the assumption of success of disruptive innovation in relation to business models. | Single case study | Results show the correct choice of business model influences the innovation process. | No |

The first main finding is the misuse of the term disruptive innovation. As emphasized in the theory presented, disruptive innovation is not necessarily a radical innovation. Perspectives were found where disruptive innovation is seen as causing major impacts with new technologies. This is not necessarily true, since disruptive innovation can be incremental and disruption might not happen so abruptly. In Portuguese, the word disruption means “rupture”; however, in the concept of disruptive innovation there is no rupture in the abrupt sense of the word. Disruption happens when a company or product begins to meet the needs of more-demanding consumers. In other words, disruptive innovation happens in sequential processes and not as a single rupture.

The sub-areas of the articles focused mainly on strategy and innovation and no article published in Marketing was found. Although the theme is innovation, disruptive innovation often has more to do with the market and consumer demands than with a technological innovation itself (Rimoli, 2005). There was no surprise in finding articles on strategy, but it is important to emphasize that Marketing needs to be more closely positioned to the area of innovation, especially regarding the concept of disruptive innovation.

In the same sense, few studies involving the BOP were found. Even though the table shows 5 articles focusing on the BOP (Zilber & Silva, 2013), when analyzing them, it was possible to notice that they were part of the same study carried out by the two authors. Research focused on strategy change in large companies that offered products to high-income customers and began to offer products to the low-income segment.

The main finding of this research shows that change happens through product adaptations and adjustments – that is, new products are not developed. Moreover, R&D investments focused on wealthy segments. Considering the perspective where disruptive innovation is usually an incremental innovation, this adaptation is common; however, this goes against the literature on offering products to the BOP segment, which needs products designed specifically for them, rather than product adaptations offered to high-income customers (Govindarajan & Trimble, 2013; Prahalad, 2012; Viswanathan, Shultz, et al., 2014).

It was observed that most of the articles use the case study method (single or multiple) to analyze disruptive innovation in a product, service, company, or technology. The results usually concentrate on describing the case and company history, product attributes, or the benefits of innovation.

The results generally show that there is a long way to go in the promotion of innovation synergy with studies in the low-income segment. There is no such synergy between innovation and Marketing. Moreover, among the articles analyzed, surprisingly, only 13 published studies were found – many of them still in congress annals. The results of this article have generated insights that can be used in future research involving all these concepts, since there is real academic and market appeal for the theme.

Final considerationsThe article presented literature on disruptive innovation, emphasizing its concepts in the low-income market. In addition, a review of national publications on the concept in the Business Administration was presented. The implications that this article seeks to highlight are more related to the scope of academia than management. The findings show that national publications on disruptive innovation are rather scarce. When found, they are usually in events annals and not in scientific journals.

Another highlight is the relationship of Marketing with the concept of disruptive innovation. Despite being a theme related to innovation, large investments in technology for its creation and implementation are not necessary. The key to the development of disruptive innovation is in the market and consumer needs, especially BOP customers. In other words, rather than focusing on hardware, software, and working in laboratories, it is necessary to have a marketing and market perspective.

In addition, few studies in Business Administration and none in Marketing were found. In relation to the BOP market, only 5 papers were found, which were actually from just one research project. This shows that there is much to be done to advance research in the way of integrating innovation, marketing, and the low-income market.

The last criticism is directed toward product and service development for low-income customers that focus on product adjustment and adaptation for the high-income market, instead of starting a new project for this potential market. It is not only through adjustments and adaptation that real results are achieved in this market. It is necessary to develop customized solutions so that there are no mistakes in the use of these products.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.

Keywords used in database search engines: “inovação disruptiva,” “disruptive innovation,” “tecnologia disruptiva,” “disruptive technology.”

Brazilian Administration Review, Cadernos Ebape, Organizações & Sociedade, Revista de Administração Contemporânea, Revista de Administração de Empresas, Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, Revista Contabilidade & Finanças, Revista de Administração da USP, Revista de Administração Pública, Brazilian Business Review, Revista Eletrônica de Administração, Revista de Administração Contemporânea, Revista de Administração Mackenzie, Administração Pública e Gestão Social, Base, Desenvolvimento em Questão, Economia Global e Gestão, Faces: Revista de Administração, Gestão & Regionalidade, Revista de Administração e Inovação, Revista de Administração da UFSM, Revista de Administração da UNIMEP, Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Inovação, Revista Brasileira de Inovação, Revista Inovação Tecnológica, Revista Design, Inovação e Gestão Estratégica, Revista Interdisciplinar de Marketing e Revista Brasileira de Marketing.