Social innovation's fundamental objective is to promote life quality. Any new initiative with this purpose might be considered a social innovation. From this concept, it is perceived as social innovation the efforts of the Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE), an initiative originated in Pentecoste, a municipality in the state of Ceará, located in the Brazilian semiarid region. This program has benefitted hundreds of youngsters, enabling their access to knowledge and further approval in university entrance exams. The educational method of collaboration in cells made possible broadening the horizons of many youngsters coming from rural communities, even when lessons were ministered under a tree in the middle of a farm. The objective of this study is to identify the dimensions of social innovation, according to Tardif and Harrisson (2005), existing in the PRECE's proposal. It is aimed to evidence how the initiative is composed, bringing to light the essential elements that make it social innovative. A case study of PRECE was carried out through qualitative research. Data were collected via semistructured interviews with members of the direction and coordination of the Program, and analyzed using the software NVivo 10. The results highlighted how the dimensions of social innovation are composed within PRECE. This research contributes by foregrounding a social initiative that has been capable of changing individual realities in the Brazilian semiarid and showing how such initiative is constituted in the social innovative perspective.

Social innovations emerge as a way to improve life quality of people who need means to change their realities. In the definition provided by Neumeier (2012), social innovations might be understood as transformations in attitudes, behaviours or perceptions of a group who gather in a network of interests aligned with the group's experiences and these changes lead to new and improved alternatives of collaboration.

Bacon et al. (2008) highlight three critical factors to explain the dynamics of social innovation. First, the willingness to change, coming from the awareness about a threat, flaw or from the feeling of a new opportunity. Second, the presence of internal capacities to promote such change, which include leadership and a culture related to it. Third, the access to external resources to help transformation to occur; these resources comprise people, money, skills and networks as well as the positive feedback from the benefitted audience.

In this regard, the Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE – Program of Education in Cooperative Cells in Portuguese) was created to contribute with the education of young people from rural areas, enabling them to become students in the Federal University of Ceará (hereby also called by its Portuguese acronym UFC).

Using a cooperative learning methodology, PRECE became an innovative movement that has improved the life quality of hundreds of youngsters. The program was started in 1994 in a manioc mil in the rural community of Cipó, located in Pentecoste, a municipality in the state of Ceará. Over the years, the Program breached the borders of the community and, currently, its methodology is incorporated as a UFC extension project, the Program is defined in this article as a social innovation.

The objective of this study is to identify the dimensions of social innovation in the PRECE's proposal, according to Tardif and Harrisson (2005). Identifying these Dimensions in the case chosen, based on the mentioned authors, took place due to the interest in verifying the applicability of a Canadian model in a context very diverse from the ones that enabled assembling the table of reference, thus, promoting a dialogue between the developed reality and the one situated in the Brazilian semiarid. It was believed that persuasion, element evidenced by Siggelkow (2007), can be found in the specificities of the context chosen and in the impact that the educational initiative had in the region. In this sense, the initiative became, over the years, acknowledged and it was later incorporated as well as institutionalized by the state.

A qualitative methodology was employed to operationalize this research. In order to attain greater methodological rigour for the case studied, as suggested Mariotto, Zanni, and Moraes (2014), there was an effort to refine and interpret the data collected by employing the content analysis technique via the software NVivo 10. This tool permitted to reach more respectability in the process of analysis, although keeping a positivistic focus, but maintaining the importance of the case's specificities. Through this tool, eight semistructured interviews were analyzed, which had been carried out in Fortaleza and Pentecoste, with the individuals in charge for operationalizing PRECE's activities.

The findings foregrounded that the social innovation dimensions from the analytical table from Tardif and Harrisson (2005) were identified in the PRECE, confirming it as a social innovation to the context studied. Even though the case's characteristics allowed to consider it a social innovation, testing the identification of dimensions enabled to classify it as such with more rigour.

Theoretical backgroundsSocial innovationAccording to Schumpeter (1985), innovation a dynamic element in the economy, which grants the entrepreneur the fundamental role of economic development promoter. Considering innovation in a general perspective, The European Commission (1995) recognized that innovation cannot be seen only as an economic mechanism or technical process. Innovation is also a social phenomenon through which individuals and societies express creativity, necessities and aspirations.

According to Hillier, Moulaert, and Nussbaumer (2004), an innovation policy implies in the capacity of regenerating several forms of capital (social, environmental and institutional) to promote development, relying on new governance relationships based not only on one kind of agent, but also in the cooperation among different sort agents.

Another central issue is that one of the basic concepts of innovation lies in its width. The Oslo Manual (OCDE, 1997) outlines, addressing to the degree of novelty, innovation as Minimum, Intermediate or Maximum. The first is linked to what is understood as new to the “company”, the second highlights what is a novelty in a region or country and the third considers what is new to the world.

Regarding innovation in its social kind, Pol and Ville (2009) highlight that the concept of social innovation has been used in juxtaposed ways in different disciplines. In these discussions, it can be granted as the engine for institutional change, as an alternative with social purposes, as an innovation oriented to the common good and as addressing to needs not yet fulfilled by the market.

Comparing the two kinds of innovation previously highlighted, Lundstrom and Zhou (2011) identify some differences between business and social innovation. The former aims at capitalizing knowledge to reach commercial interests, whereas the latter has the commitment with social progress by solving problems where economic resources are scarce. Concerning actors and investors, it is stressed that business innovations are typically invested by companies, despite these organizations may also work with social issues. Furthermore, the government, non-governmental organizations, foundations and individuals can perform social innovations. Regarding the criteria for success, the performance of business innovations is measured through the participation in the market and by profit rates, whereas in social innovation is assessed by the intensity of social improvements and progress.

Howaldt and Schwarz (2010) emphasize that, in as much as bring forward the new paradigm of innovation promoted by chronological changes, transformations concerning the object of innovation have also taken place. This view opposes to the classical technical paradigm from the industrial society, which was immersed in the idea of development.

Taking into account social innovation specifically, Heiskala and Hämäläinen (2007) convey that social innovations are often created as a response to rapid technical-economic changes, which create new social problems not possible to be corrected by prior political mechanisms. This demand tend to be motivated by the search for equity.

To the Center de Recherche sur les Innovations Sociales (CRISES, 2012), social innovation is understood as a process started by social actors to respond to certain aspirations. These goals might be addressing to a need, supplying a solution or being benefitted by an opportunity to change social relationships; transforming a scenario or proposing new cultural guidance for improving life quality or conditions in a community.

Franz, Hochgerner, and Howald (2012) reinforce that social innovation has been ignored as an independent phenomenon, being disregarded as one to be target of social and economic scrutiny. The concept of social innovation seldom appears as a clearly outlined specific term. These authors evidence social innovation as being normally used as a descriptive metaphor in the context of social and technological changes. Neumeier (2012) emphasizes the importance development programs and other incentives have as catalyzers of regional social innovations, taking into account the context of rural development in his analysis. Furthermore, this author conveys the need to approach these initiatives with more depth, paying appropriate attention to the shape these programs are assembled, thus, allowing the creation of sustainable social innovations.

Corroborating with the definitions, characteristics and specificities brought forward, Cajaiba-Santana (2013), social innovations emerge through changes in attitudes, behaviours or perceptions, elements leading to new social practices. This author stresses that these changes do not only occur in the way social agents act or interact with one another, but also through transformations in social life, enabled by the context where these actions happen by the creation of new institutions or social systems. Therefore, what is underlying in social innovation is not the problem to be solved, but the social transformations solving the problem brings.

Dimensions of social innovationCRISES’ members are in the center of a joint effort with civil society and contribute actively to knowledge transference activities, for such, many studies have been performed in partnership with other actors. In addition, the scholars connected to the Center belong to several fields like anthropology, geography, history, mathematics, philosophy, industrial relations, management sciences, economy, political science, sociology and social work. Because of the assertive role CRISES has in the social innovation field, the dimensions proposed in Tardif and Harrisson's research (2005) were chosen to operationalize the identification carried out in this article.

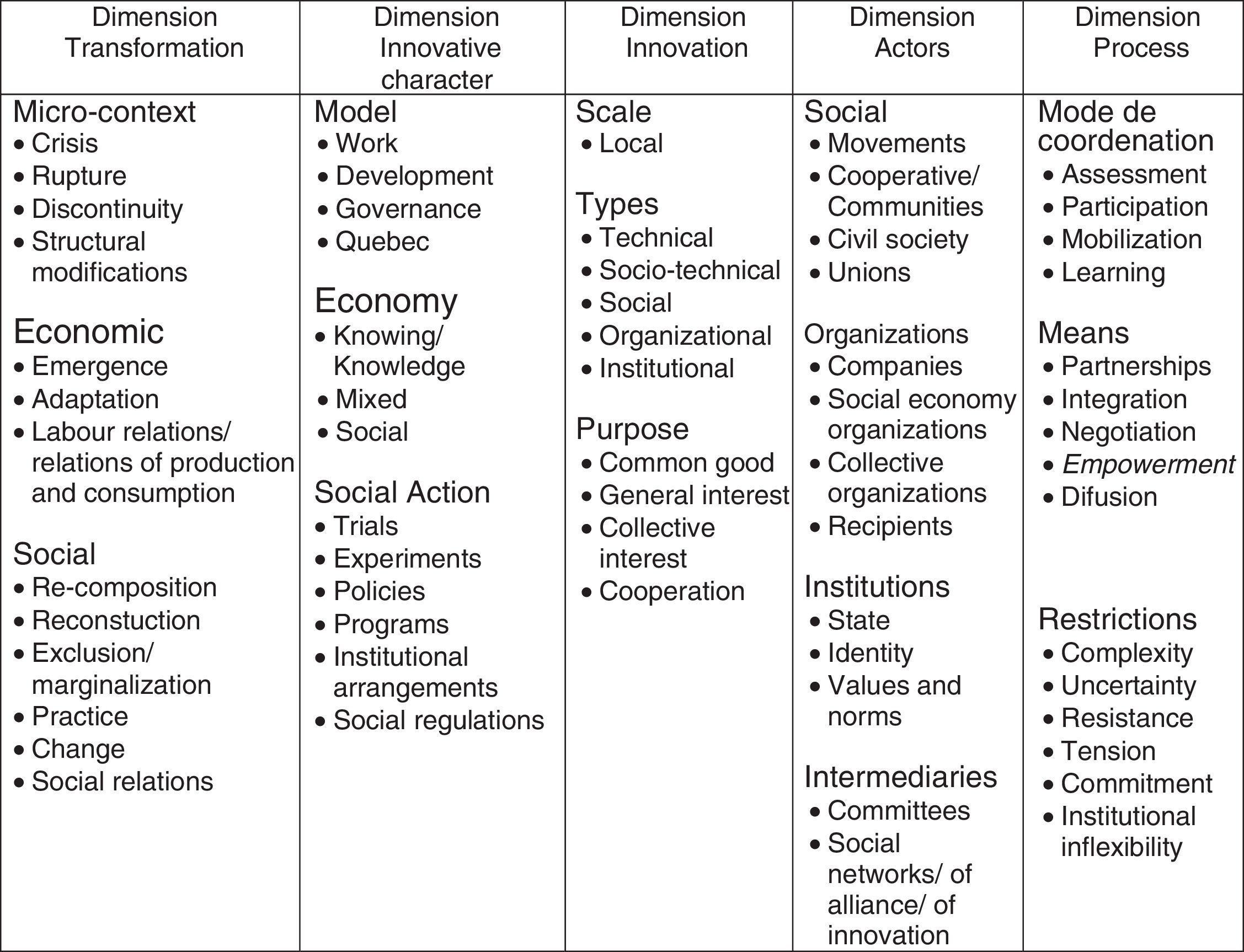

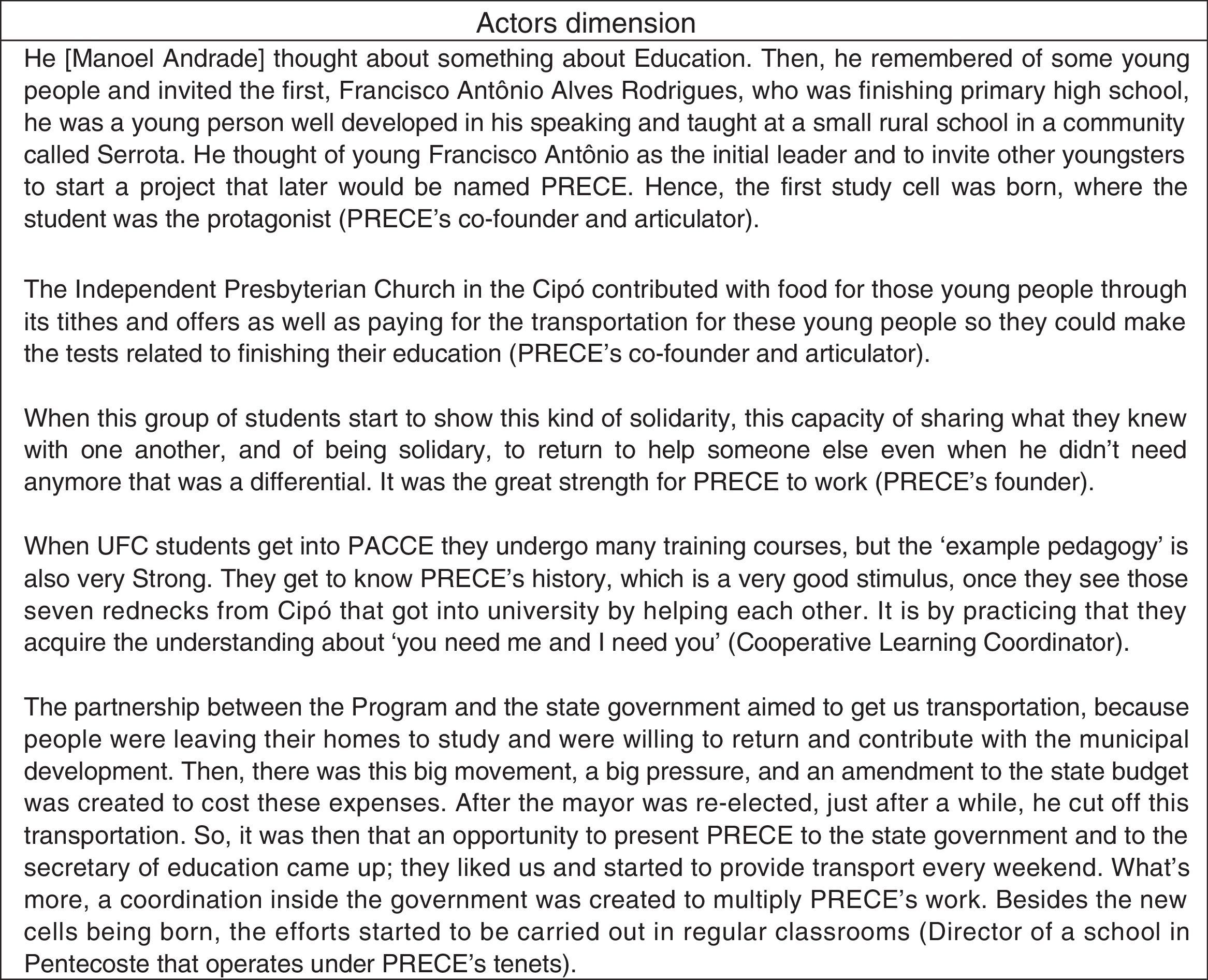

Starting with the analysis of 49 scientific papers published by the Center, Tardif and Harrisson (2005) verified how the integration between researchers from the Center was settled and to what extent these members knew other productions from CRISES and referred to them. The document resulting from the mapping process, besides multiple identifications, introduced the table called “CRISES’ Conceptual Encyclopaedia of Social Innovation”. This table outlines five dimensions for social innovation: Transformation, Innovative Character, Innovation, Actors and Process. In this regard, Maurer (2011) as well as Souza and Silva-Filho (2014) used the term “dimensions” to operationalize elements from the table in distinct case studies.

Fig. 1 displays the “CRISES’ Conceptual Encyclopaedia of Social Innovation”, elaborated based on the study by Tardif and Harrisson (2005). The Encyclopaedia presents five dimensions of social innovation.

CRISES’ conceptual encyclopaedia (dimensions of social innovation). Source: Adapted from Tardif and Harrisson (2005) and Maurer (2011).

The first element, Transformations, connects with the context wherein the social innovation is comprised. This dimension emphasizes macro and micro issues casting influence over the initiative. Crises, ruptures, discontinuities and structural modifications compose the subtopics within this contextual item.

Social innovations rising in the identified context might be influenced by social and economic matters, which may require adjustments or new responses. Such transformations promote initiatives leading to the search for innovative strategies. Transformations regarding concerns about polarization, exclusion and social marginalization will demand answers that may improve the well-being of people affected by such challenges.

Concerning the Innovative Character dimension, Tardif and Harrisson (2005) affirm that innovations are responses to crises and are characterized as novelties in their contexts. These new initiatives represent attempts and experiences in the implementation process. When succeeded, they might be institutionalized and transformed into new labour, development, governance and solidarity economy models.

Analysing the Innovation Dimension, Tardif and Harrisson (2005) divided different experiments of social innovation in five kinds: technical (technological), socio-technical, social, organizational and institutional. These authors affirmed that social innovations are local processes started by different actors aiming to transform their interactions. On the one hand, these actors change their interplay with the organizational and institutional environment. On the other hand, such actors have the objective to neutralize the effects of crises in as much as they try to conciliate different levels of individual and collective interests. These social innovations take place locally and can be guided towards the common good, general or collective interests.

The Actors Dimension emphasizes the collective learning emerging from innovation due to the number of people interested and involved. It is hoped that cooperation amid all actors occur aiming to ensure “good governance” practices. In this dimension, actors such as cooperatives, associations, trade unions and community movements are included. Moreover, organizational actors like companies, social economy and collective organizations are included as well as their beneficiaries. Institutional actors such as the State, identities, values and norms also belong to this group like committees and networks of social alliance to promote innovation also fall into this dimension. Partnership and cooperation are key elements here.

The last element, Process, deals with the dynamics, complexities and uncertainties in relationships between actors. Institutional rigidities constraining the innovative process are also added to this dimension.

Furthermore, the forms of coordination, means (interpreted as relationships established between different parts), and constraints to implementing social innovations, which may influence or reduce the innovative potential of a project are verified in this last dimension. According to Tardif and Harrisson (2005), innovation brings to light the importance of collaboration and participation of different stakeholders. Hence, the final goal in an innovative project is the involvement of all participants and their cooperation throughout the process.

The dimensions composing the table introduced in this section map the path taken by social innovations beginning at the contexts where they are present. These dimensions also overlap relationships, presenting challenges to the implementation and permanence of social innovations.

MethodologyAs Konstantos, Siatitsa, and Vaiou (2013) indicate, socially innovative initiatives are developed in reaction to increasing inequalities as well as to processes of social exclusion, mobilizing different resources. In this regard, understanding such phenomena requires specific methodologies to approach and learn along with the actors, objectives and practices comprised.

The current qualitative research, regarding its nature, is classified as descriptive. The former is carried out to answer a research question with few previous related studies from which information might be collected; this type of research focuses on acquiring familiarity with the area, to investigate it later with more rigour. Among the typical techniques used to do so are the case studies. Whereas the latter, the descriptive research, is interpreted as the one seeking to outline the behaviour of phenomena as well as to identify characteristics of a determined problem (Collis and Hussey, 2005). This case can be also outlined as representative or typical (Yin, 2010), insofar as it aims to capture the conditions of its operationalization, presenting the lessons engendered by the initiative.

Considering these points, the case study of the Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE) was adopted as investigation strategy to define it as a social innovation, relying on the dimensions of analysis presented in Tardif and Harrisson's (2005) table. According to Yin (2010), the case study is the most suitable strategy when analysing contemporary phenomena, included in a specific real life context.

The data were collected through semistructured interviews with eight individuals who are closely linked to PRECE's trajectory and the talks took place in Fortaleza as well as in Pentecoste. These people are: the Director of the Popular Cooperative School of Pentecoste; the Vice-Director of the Popular Cooperative School of Pentecoste, the PRECE's Coordinator of Public Relations, the PRECE's co-founder and articulator, an Educator and articulator, the Director of a school in Pentecoste that operates under PRECE's tenets, the Coordinator of Cooperative Learning and the PRECE's founder (Manoel Andrade – his name appears here because it was mentioned many times in the interviews. Mentioning him in this section will help to understand interviewees’ accounts during the discussion of results). These interviews lasted from 20min to 1h and, following the objectives aimed here, brought forward how PRECE can be regarded as a social innovation.

The information provided was analyzed with the NVivo 10 software for qualitative analysis. As a result, this tool made possible to create “nodes” corresponding to each dimension. Using the content analysis, information comprised in the transcribed interviews were distributed in each dimension (node). According to Bardin (1977), the content analysis technique is composed of a set of methodological instruments that are applied to diversified discourses. The gathering of such techniques absorbs the investigator who seeks hidden elements, latent aspects – what is not apparent – the potential novelties, in other words, the “unsaid” retained in a message. According to the Bardin's (1977) guidelines, three stages comprised analyzing the data: 1) pre-analysis, 2) exploration of material and 3) treatment, inference and interpretation of results. Considering this path, the analysis performed is defined as “thematic” because an “intuitive codification” was performed (Oliveira et al., 2003).

After concluding the distribution process, a new content analysis was done within each node to make emerge relevant information about each dimension, feature that permitted to analyze PRECE understanding the different elements using the dimensions of social innovation, based on the reference table.

Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE)The information in this section was collected from PRECE's and PACCE's websites.2 In 1994, the Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE – Educational Program in Cooperative Cells in Portuguese) was founded by a group of seven youngsters in a rural district called Cipó. This location is part of Pentecoste, a municipality in Ceará, situated in the Brazilian northeast. The group was encouraged by a professor of the Federal University of Ceará to study together, this professor was born in Cipó. Their focus, at first, was to obtain a high school diploma and, later, as the project developed, to take the entrance exams needed to become students at the UFC.

Over time, the program increased its prestige with the surrounding communities, as it achieved results such as having one of its first students and founders approved in the first place for Education at the UFC. In the early 2000s, as a result, more students walked, drove or cycled from near communities to take part in the program. In as much as the program began scaling up, problems appeared and PRECE started to employ new strategies to keep delivering outcomes.

To solve spatial problems, PRECE's founder suggested the students to form study groups in their own communities, spreading the methodology and the idea, which helped the movement to grow even further. Students, who began gathering in places such as community associations, started the Escolas Populares Cooperativas (EPCs – Popular Cooperative Schools in Portuguese). Similarly to PRECE's founders, this new group of students aimed at going to UFC to get a college degree.

PRECE as a whole operates by using a kind of group study called “cells”. These cells are formed by a group of five to seven students who get together to learn more about one subject; the cell member with more background on the issue facilitates the learning. These roles, however, are not static. Although a student holding more knowledge on one topic becomes a facilitator for the rest, such feature does not impede other members to collaborate if they wish or if the group needs their assistance. During the weekends, UFC students who might be former PRECE's members or not, assist these groups as well.

The operationalization of these cells is simple. The need for financial resources is low and most funding comes from projects PRECE approves with funding supporting agencies and foundations.

In spite of its challenges, PRECE has been capable of attaining results such as placing more than 600 students in different universities. Moreover, these youngsters have been moving on to become masters and PhDs. To date, the program has been operating through 15 EPCs in four different municipalities in the Ceará semiarid: Apuiarés, Paramoti, Pentecoste and Umirim.

PRECE's founder, along with the Federal University of Ceará, helped PRECE to become an extension program of the institution in 1998. Such status, at that time, provided transportation for students who were approved and needed to return to their communities. Later, this partnership evolved and gave birth to a bigger UFC extension project operating under theoretical cooperative tenets. The objective, in this case, was to prevent students from dropping out, especially in courses that require deeper mathematical background. In this regard, evasion is a problem because dropouts both lose the chance to get a college degree and make university lose resources coming from the government due to a smaller number of enrolled students.

Because of these efforts, the Programa de Aprendizagem Cooperativa em Células Estudantis (PACCE – Cooperative Learning Program in Student Cells in Portuguese) began in 2009 with the purpose of motivating students to form study groups to help each other, inspired in PRECE's “cells” model. The outcome desired was to reduce evasion indices as well as increase conclusion rates. The Coordenadoria de Formação e Aprendizagem Cooperativa (COFAC – Coordination of Formation and Cooperative Learning in Portuguese) operationalizes the program that is supervised by the Office of Undergraduate Studies at the UFC. Presently, the program has about 250 scholarship students from different campi, and besides receiving training about the methodology, these students are also responsible for organizing cells that have to develop learning projects on a topic of free choice. They are required to perform 12 weekly hours of activities, and in exchange receive R$ 400 (US$ 133.33) during ten months.

Results and discussionThe data collected made possible to identify the presence of the five dimensions comprised in the Tardif and Harrisson's (2005) table. This section introduces the discussion about the data gathered, sustained on interviewees’ lines, which illustrate these dimensions and permit a better comprehension about the case's singularities.

The lines highlighted in this section were sheltered in the corresponding “nodes” created in NVivo 10. Later, the content analysis technique made possible to identify the information about each one of the five nodes, thus, the extracts’ interpretation was directed to such purpose.

A second content analysis allowed reading the extracts, which were also divided and inserted in the nodes. In this sense, the most significant lines for each social innovation dimension can be seen at the next subsections.

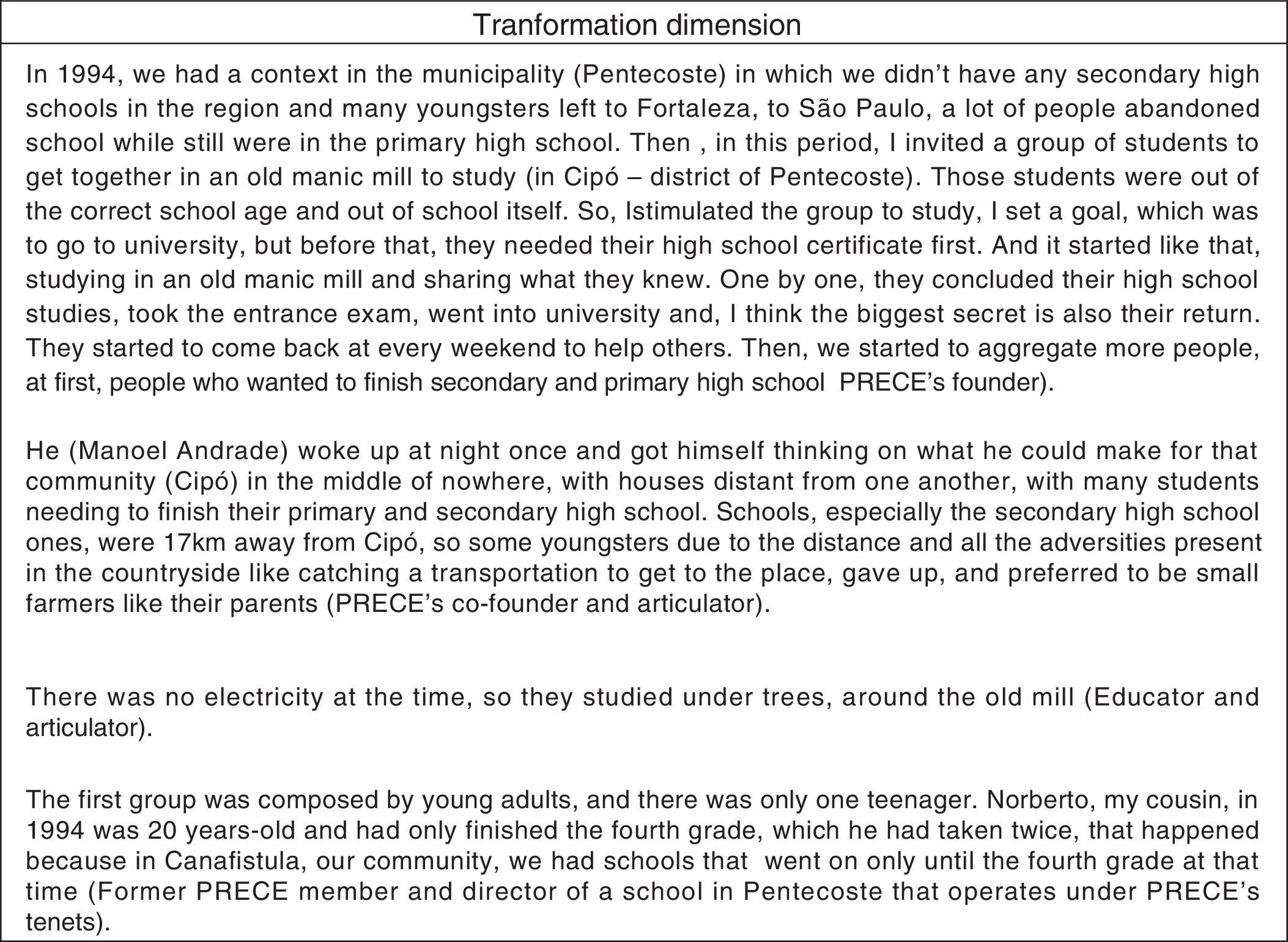

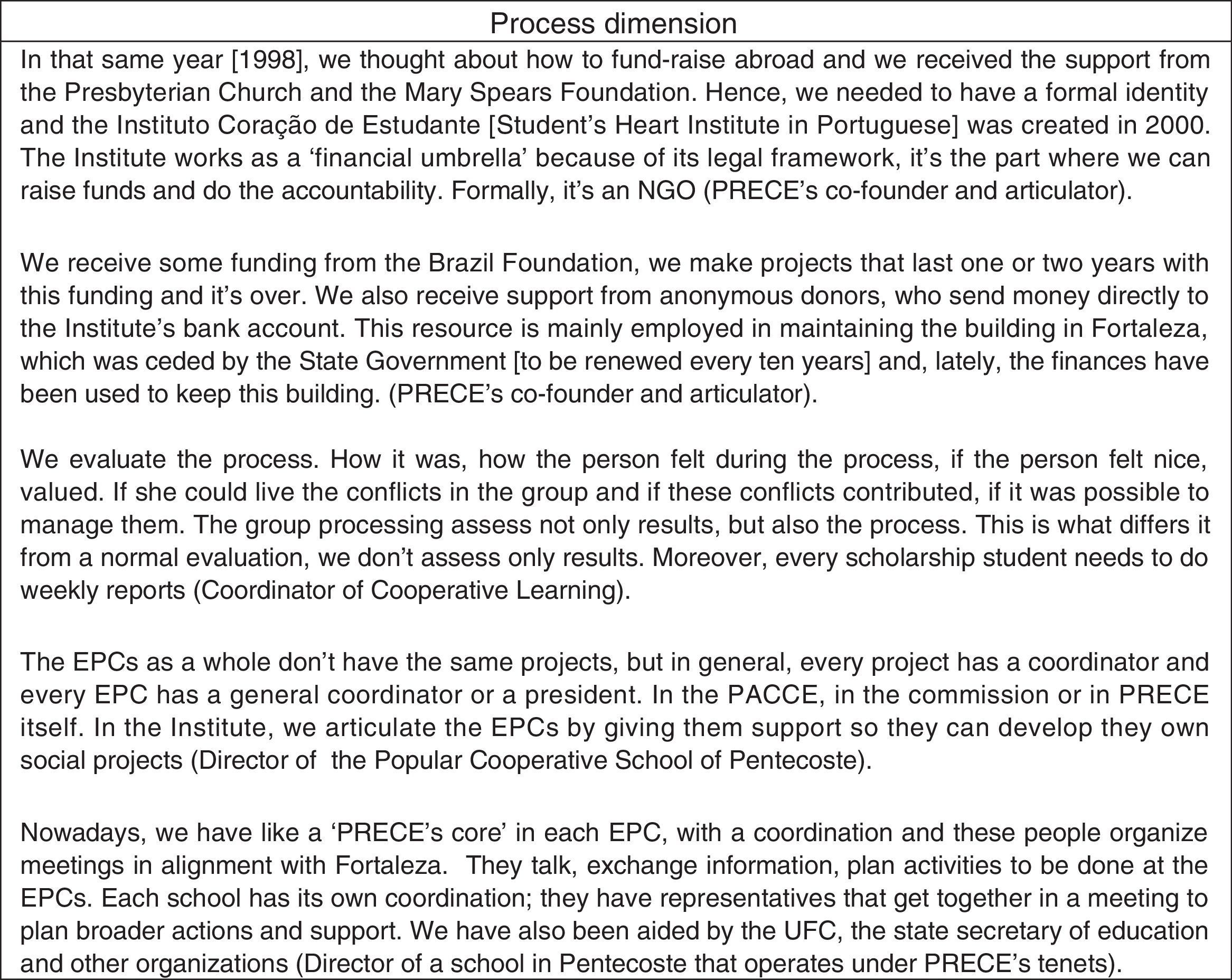

Transformation dimensionAs foregrounded in the PRECE's description, interviewees highlighted the importance of the context wherein the Program was initiated. The limitation young people had, regarding their access to superior education, was a central factor for the PRECE's founder, to seek a way to contribute not only in Cipó, but also in the surrounding communities (Fig. 2).

Considering the economic aspect, the accounts systematically evidenced the lack of financial resources the inhabitants of Cipó had at the time PRECE was conceived. In this poor community, formed by farmers, the few schools available offered until the fourth grade of primary high school. Commuting was an obstacle; problem that made students quit and look for jobs in agriculture as well as in livestock farming like their parents, even though these occupations granted smaller chances for financial autonomy.

Regarding the social issue, young people from the region remained excluded because of their limited schooling; the precarious teaching they could access constrained their capabilities to search for better jobs and income opportunities.

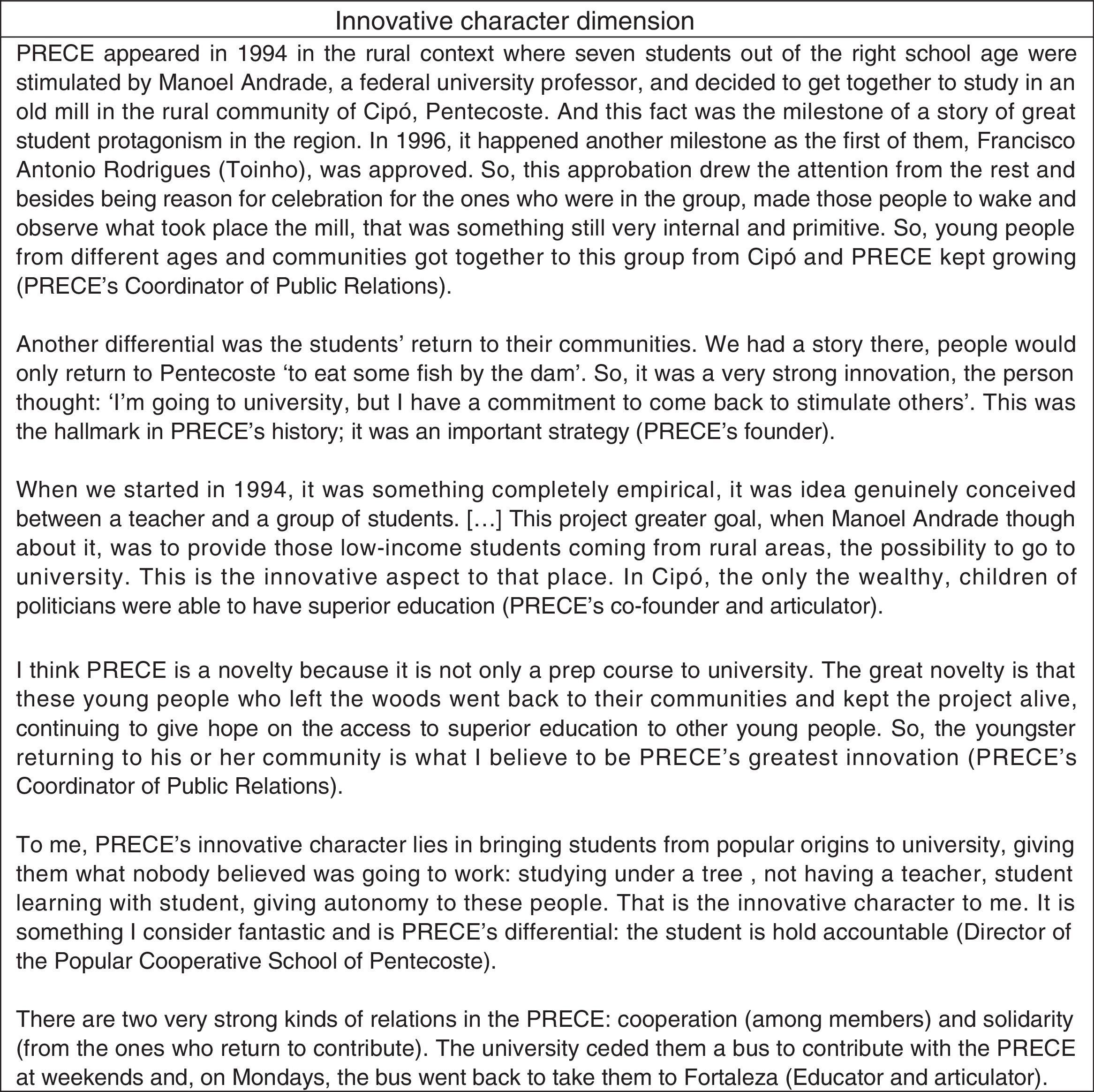

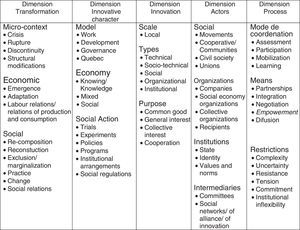

Innovative character dimensionPRECE's teaching model, in which students are responsible for sharing knowledge based on the topic they are more proficient, was outlined as an essential innovative character to the Program's proposal and success (Fig. 3).

Currently, PRECE operates in many communities and its model was adopted as an extension at the Federal University of Ceará and in professional schools of the State Government. To date, the Program has undergone different adjustments and faced many challenges as a new proposal in the region.

It is important to bring forward that experimentation was important to conceive the novel ways to tackle the challenges identified. In addition, it was because of such experiments, as the ones performed in the old manioc mill, that PRECE emerged and went on changing its region.

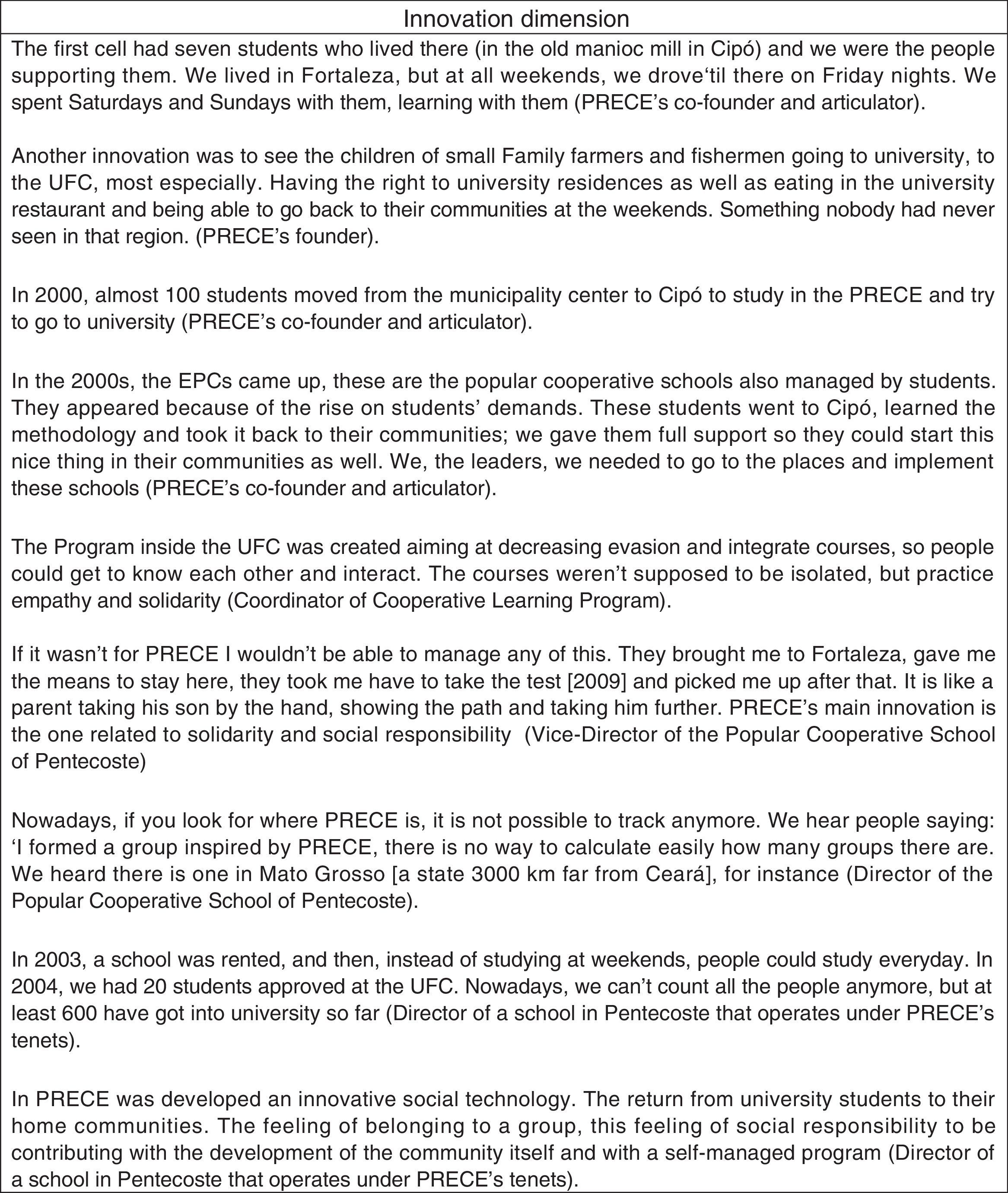

Innovation dimensionPRECE began in Cipó, a district in the municipality of Pentecoste in the semiarid region of Ceará. This community struggled with problems much similar to others in that region. Although it was started in a simple community in the poor countryside, the initiative was able to go beyond its borders. In this regard, PRECE was also acknowledged as an innovative effort in the USA through Professor Manoel Andrade, while he was there studying for his post-doctorate degree and had contact with the Cooperative Learning theory, which was later incorporated to the Program (Fig. 4).

PRECE's fundamental role, at its inception, was to provide poor youngsters the possibility to finish their basic studies and get into public universities. The common good, cooperation and solidarity have been the Program's trademarks, characteristics systematically evidenced in the interviews. The program alumni, known as “precistas”, communicated a feeling of belonging and accountability with the initiative, once they have been motivated to build new possibilities together as well as to help others who were in the same conditions and shared equal needs.

Actors dimensionDuring its creation, different social actors were essential for the Program to endure. Encouraged by Manoel Andrade, students realized they could build a movement that would transform their lives and bring new perspectives for their future. Inhabitants from Cipó as well as Manoel Andrade's relatives got involved in the cause, as they perceived its potential (Fig. 5).

The program also had other essential supporters for its structuration and growth. The church in which Andrade congregated made available part of the resources. Moreover, the assistance provided by the UFC to PRECE's former members was fundamental to enable these students to live in the capital, go back to their communities every weekend to help others.

International supporting organizations such as the Konrad Adenauer and the Brazil Foundations aided the Program. In addition, the Ceará State Government, which has incorporated PRECE's methodology in a prototype school in Pentecoste and granted a space so the Program could operate in Fortaleza, has also provided such assistance.

Finally, several volunteers and formal collaborators believed in the idea's potential and made possible to bring about the project, changing the lives of hundreds and helping so the Program could become a reference in education and cooperative learning in the state of Ceará.

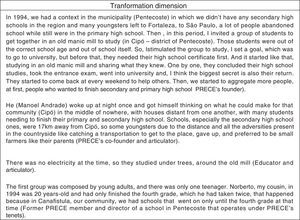

Process dimensionThe processes established to run PRECE have been systematically assessed by different participants, starting by the students, who evaluate the performance of their cells at the end of each day. They consider how learning took place, the roles engaged by each member as well as the wrongs and rights the group performed (Fig. 6).

Besides the processing of information carried out by students themselves, as highlighted in the accounts above, Popular Cooperative Schools hold a coordination supervising these assessments. Conversely, the PACCE has its own means to evaluate what the UFC group is doing and they receive support from a team focused on articulating these evaluations as well as further improvements.

Throughout PRECE's history, there has been much restructuration. Processes needed to be created and adapted so the essence of the Program's proposal could be kept. Therefore, in as much as PRECE grew in visibility and demand, new relationships have been set up and more formalized procedures have become necessary to ensure good results.

Final remarksUnderpinned on the understanding of social innovation as one aiming not at making economic profits, but at improving the well-being of its beneficiaries, this research sought to identify the characteristic multidimensions of a social innovation through the case study method. In this regard, by using table proposed by Tardif and Harrisson (2005) as reference it was possible to identify the presence of their five dimensions for social innovations: Transformation, Innovative Character, Innovation, Actors and Process.

The Programa de Educação em Células Cooperativas (PRECE) emerged as an alternative to change the reality of poor young people and brought forward the search for improving the well-being of these people through innovative initiatives. The innovation conveyed by interviewees is present, especially, in the approach of studying cooperatively without a teacher in the traditional content-centred perspective. As a result, each student has become a protagonist in his education as well as to his peers. Another innovative element is the fact that these youngsters, as they got into university, have returned to their communities and assisted those who wanted to reach the same goals. Therefore, solidarity was evidenced as a fundamental element in the constitution of this social innovation.

In this sense, the interviews supported the elements comprised in the Tardif and Harrisson's (2005) table as such elements were identified in the data. Hence, it is possible to affirm that PRECE is indeed a social innovation.

The case study permitted to explore PRECE's central aspects and describe them through the speech of its founder as well as other members who have followed the project during its trajectory and still act either as coordinators or in other positions, managing the initiative in the necessary ways. Furthermore, this research contributes by foregrounding an initiative that was capable of shaping realities in the Brazilian semiarid, evidencing how such undertaking is constituted as a social innovation.

Nevertheless, the number of interviews might be posed as a research limitation, these talks, however, took place based on interviewees’ availabilities, another limitation, regarding information triangulation, was related to the impossibility to gather other sources of information to the case. Thus, further research can seek other beneficiaries and promote a broader study. Another suggestion for future research lies in trying to qualify PRECE using a different classification for social innovations to check if the Program responds equally to such composition and then compare it to the one performed in this study, as well as the incorporation of other sources of evidence about the case and interviews with beneficiaries. It is believed that another vantage point may facilitate the emergence of other theoretical issues about social innovation.

Although acknowledging its limitations, this study has addressed to its purpose as well as it has socialized an important initiative to the Brazilian northeastern region, besides bringing to light the discussion about social innovation and its capabilities to modify realities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.