Intellectual property is currently understood as a strategic asset of the countries, but not every modality or subcategory it features is well known. The present work addresses the issue by weaving a general initial debate and approaching one of the subcategories of the industrial property: geographical indications. Geographical indications are mechanisms of intellectual property applicable to goods and services characterized by the place where they originated (collected, produced or manufactured), involving environmental, historical, social and cultural specificities, and according to the Brazilian regulation, Geographical indications are divided into two types: indications of origin or appellations of origin. In this manner, it is intended at specifically analyzing functions and impacts assigned to the geographic indications in papers published up to 2015 and available in CAPES’ journal database. In order to do so, it was conducted a comprehensive review with 26 papers (all available on the database in analysis). The results point to two major contributions: the understanding as to the functions and impacts of Geographical indications in the country and the establishment of categories for analysis. According to these, Geographical indications can be designed as system of protection (to the consumer and the farmer); marketing tool (emphasizing the difference from a product or service); rural development mechanism (since it can influence on the generation and maintenance of employment, income distribution, local identity, etc.); and means of preservation (of culture, savoir-faire, and even ingredients).

“The acceleration of the information process and the development of industrial economy have required, since the Renaissance, the creation of a new category of property rights” (Barbosa, 2010, p. 23). If the major objects of trade of the twentieth century were oil, iron and unskilled labor, in the twenty-first century they are information, technology, and knowledge (Shaver, 2010).

Intellectual property (IP) is considered a highly relevant factor in the contemporary context, when the development of a country, region or specific location can be associated with creative and entrepreneurial ability of individuals and organizations (Matias-Pereira, 2011a; Shaver, 2010; Sherwood, 1992; Vieira & Buainain, 2012). Intellectual property rights are not reduced to economic issues of “incentive” and “access”, but imply many other aspects and variables such as relevant social and cultural issues (Basso, 2011; Trentini, 2006). In this manner, it is paramount to understand intellectual property rights and the impacts attributed to them.

Like other developing countries, Brazil has moved toward appreciation and more credible intellectual property (Vieira & Buainain, 2012). Although not so well known by Brazilians (public and private managers, producers and general society) (Mendes & Antoniazzi, 2012; Shaver, 2010), geographical indications (GIs) are included in these instruments. They apply to goods and services characterized by the place where they originated (collected, produced or manufactured), involving environmental, historical, social and cultural specificities. According to the Brazilian regulation (Law n° 9279/1996), are divided into two types: indications of origin (IO) or appellations of origin (AO) (BRASIL, 1996, 2013; BRASIL & MAPA, 2014).1

Despite recent formalization, geographical indications date back to the 4th century BC, since the act of asking for products by the names of the lands where they came from was usual among the ancient Mediterranean peoples (Greeks and Romans) because they learned that products coming from certain places had particular qualities (Faria, Oliveira, & Santos, 2012; Mendes & Antoniazzi, 2012). In Brazil, recent discussion started in the 1990s after the Law of Industrial Property (Law n° 9279/1996).2 However, it was not until the 2000s that geographical indications were registered in the country and, more recently, there is a more intense debate and development of policy and research on the issue. By mid 2015 there were 42 geographical indications registered in Brazil (34 IOs and 8 AOs), where more than 80% of these were registered in the last five years (Medeiros & Passador, 2015). This progress also reflected in more research: in early 2015 there were 45 works of post-graduation (theses or dissertations) about the subject submitted in the country,3 where 40% are also dated from 2011 onwards.

To adopt a geographical indication implies an increase in costs for the producer both for registration and preparation and use of labels and packages (Medeiros, 2015), and it is hoped that these are outweighed by the benefits obtained (Zuin & Zuin, 2009). Geographical indications are essentially an instrument to promote products commercially, but it can generate wealth, add value, protect the producing region and generate development, expand the export of products, strengthen the domestic market, and promote the products and their historical and cultural heritage, among other issues (Castro & Giraldi, 2015). Thus, this study aimed to analyze the functions and impacts attributed to geographical indications in papers published up to 2015 and available in the CAPES Journal Portal. To this end, we made an integrative review of 26 articles (all resulting from the search on the portal with the descriptors “geographical indication,” “indication of origin” and “appellations of origin”) using content analysis. Besides understanding of the impacts attributed to GIs in the Brazilian context, this technique enables the establishment of categories that can be useful for empirical analysis in future work.

In the continuation of this introduction, we present the theoretical framework that includes an explanation as to intellectual property and geographical indications, encompassing definitions and some regulations, followed by the methodological aspects that guided the realization of this work and the steps and descriptors of the comprehensive review. In the sequence, results and discussions are presented. Finally, some considerations are made with regard to work and possibilities for future studies, and the references used are presented.

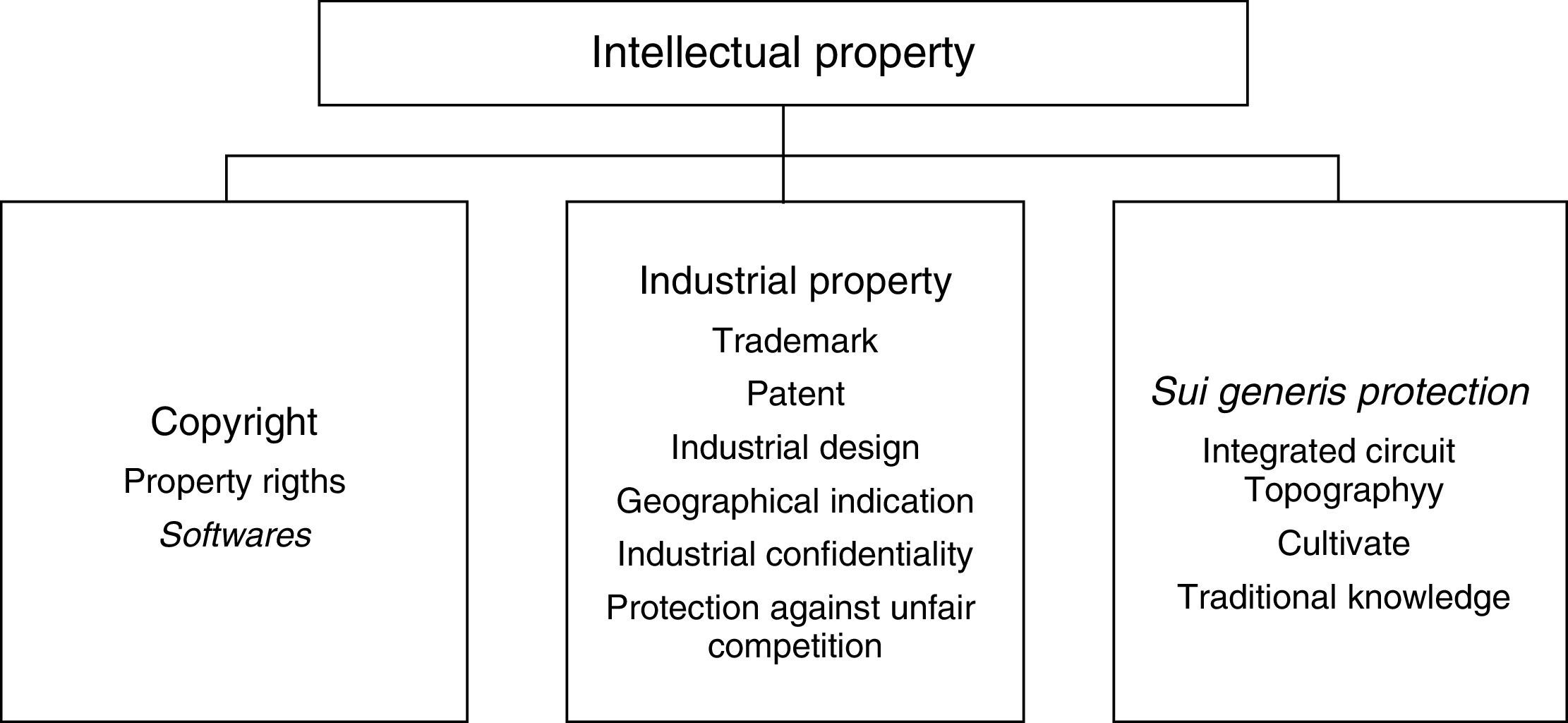

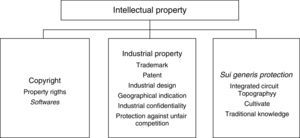

Intellectual property and geographical indicationsAccording to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), intellectual property refers to every creation made by the human mind, and it protects the interests of its creators when offering attributions regarding their creations (WIPO, n.d.). According to Barbosa (2010, p. 10), intellectual property is now described as “a highly internationalized chapter of the Law, including the field of industrial property, copyright and other rights in intangible assets of various kinds.” In this sense, it includes industrial property rights, copyright and savoir-faire. The Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), concluded in Stockholm on July 14, 1967 (Article 2, viii), provides that intellectual property shall include rights relating to literary, artistic and scientific works, performances of performing artists, phonograms and broadcasts, inventions in all fields of human endeavor, scientific discoveries, industrial designs, trademarks, service marks and commercial names and designations, protection against unfair competition, and all other rights resulting from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary or artistic fields (Barbosa, 2010; WIPO, n.d., 2004).

The necessity to enact laws to protect intellectual property is due to the following issues: political visibility (associated with the intrinsic value of the assets and the difficulty to ensure effective protection of property rights of intangible assets); attempt to promote creativity, dissemination and application of its results; promotion of fair trade, and protection to the interests of consumers. These issues can contribute to economic growth (Matias-Pereira, 2011a; Trentini, 2006, 2012; Vieira & Buainain, 2012; WIPO, n.d., 2004). Intellectual property rules determine who can use and control these assets, how and with whom permission (Shaver, 2010).

According to Barbosa (2010), the first legislation on intellectual property in Brazil places the country as one of the four first nations to have legislation on the subject. Dated from 1809, it was a license granted by Dom João VI in relation to patents. Following this initiative, other laws and treaties were established and influenced the legal and regulatory framework currently adopted. Brazilian intellectual property is ruled specifically by the Constitution, international treaties to which the country is a signatory and which have been internalized by the parental rights (Paris Convention Union), General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and Trade-related aspects of Intellectual Property Right, among others.

Previously, intellectual property held to the “existing things”, but over time it encompassed new categories in addition to products, also the rights to the production of information or information that allows the reproduction of products (Barbosa, 2010). Intellectual property in Brazil currently addresses the modalities shown in Fig. 1.

The chart in the middle deals with industrial property and is the most interesting one to this study. In addition to the Constitution and the Treaties, it is worth noting, in this context, Law No. 9279 of 1996, the current industrial property law (IPL) and its amendment (Law n° 10.196/2001). Moreover, industrial property is encouraged by n° 10.973/2004 Law, “Law of Innovation,” and Law of tax incentives n° 11.196/2005, “Good Law”. These last two are to strengthen industrial property, especially industrial creations because they seek to encourage the creation of a suitable environment for research and innovation, and to offer tax incentives for businesses. According to Silveira (2011), IPL has two classes of rights: industrial creations and distinctive signs. While the foundation of the protection of industrial creations is in stimulating new creations by granting temporary legal monopolies, the protection of distinctive signs aims to prevent unfair competition arising from confusing acts,4 and industrial creations originally belong to their authors, whereas distinctive signs – including GIs – are owned by the company (sole or corporation).

The several protection instruments mentioned above have the similarity of being legally registered distinctive signs. However, as mentioned, there are some differences. Geographical indications (appellation of origin and indication of origin) differ from other elements of industrial property, as “they results from a factual situation, which is recognized by the law. This is something that does not happen, for example, in the case of patents and trademarks” (Trentini, 2006, p. 184). It stems from the geographical designation, which includes existing natural and human factors that characterize or make the product well known.

Trentini (2006) clarifies that both trademarks and geographical indications are identifiers and differentiators, but a trademark indicates business origin while GI geographical origin. A product that is granted the right to a GI may also have an individual mark, and hence the prestige of the GI adds to the trademark; this prestige comes from factors both intrinsic and extrinsic to the goods or services such as marketing policies and competition, whereas in the GI, to the geographical environment, as the author points out.

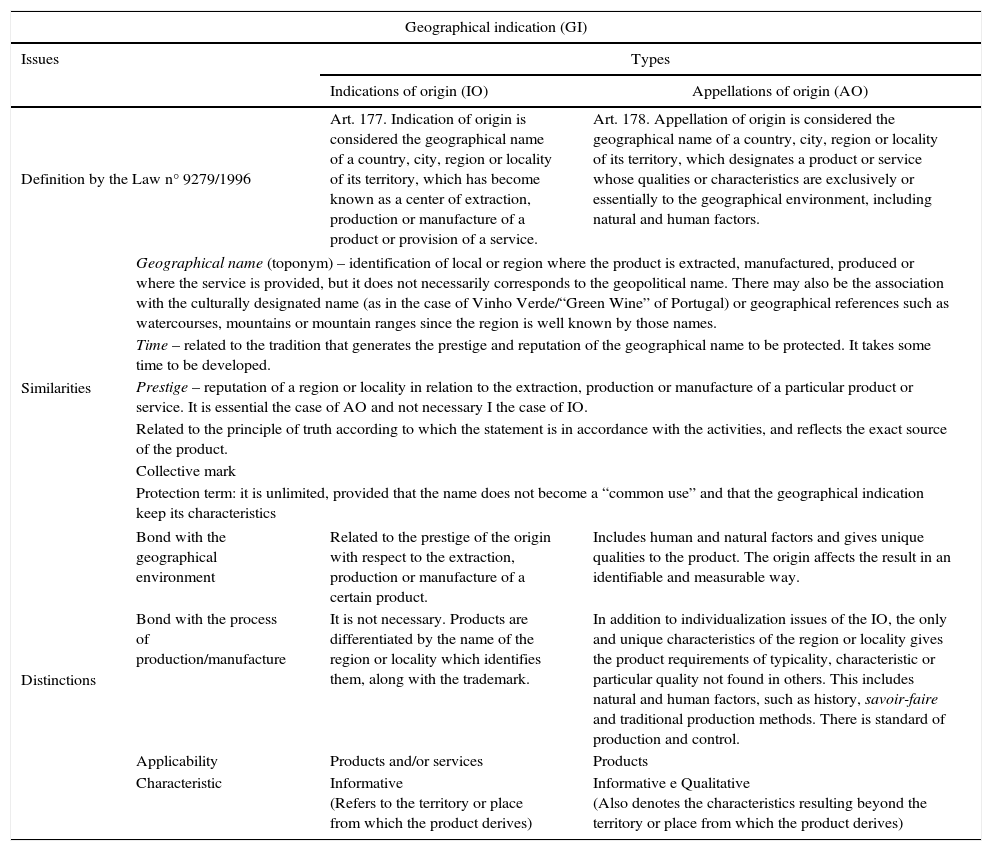

While IO refers to the origin, AO indicates qualities and characteristics of the product or service, then qualifying it. Next, see a table (Table 1) comparing the two signs in order to specify the differences.

Comparison of the types of geographical indications in Brazil.

| Geographical indication (GI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Issues | Types | ||

| Indications of origin (IO) | Appellations of origin (AO) | ||

| Definition by the Law n° 9279/1996 | Art. 177. Indication of origin is considered the geographical name of a country, city, region or locality of its territory, which has become known as a center of extraction, production or manufacture of a product or provision of a service. | Art. 178. Appellation of origin is considered the geographical name of a country, city, region or locality of its territory, which designates a product or service whose qualities or characteristics are exclusively or essentially to the geographical environment, including natural and human factors. | |

| Similarities | Geographical name (toponym) – identification of local or region where the product is extracted, manufactured, produced or where the service is provided, but it does not necessarily corresponds to the geopolitical name. There may also be the association with the culturally designated name (as in the case of Vinho Verde/“Green Wine” of Portugal) or geographical references such as watercourses, mountains or mountain ranges since the region is well known by those names. | ||

| Time – related to the tradition that generates the prestige and reputation of the geographical name to be protected. It takes some time to be developed. | |||

| Prestige – reputation of a region or locality in relation to the extraction, production or manufacture of a particular product or service. It is essential the case of AO and not necessary I the case of IO. | |||

| Related to the principle of truth according to which the statement is in accordance with the activities, and reflects the exact source of the product. | |||

| Collective mark | |||

| Protection term: it is unlimited, provided that the name does not become a “common use” and that the geographical indication keep its characteristics | |||

| Distinctions | Bond with the geographical environment | Related to the prestige of the origin with respect to the extraction, production or manufacture of a certain product. | Includes human and natural factors and gives unique qualities to the product. The origin affects the result in an identifiable and measurable way. |

| Bond with the process of production/manufacture | It is not necessary. Products are differentiated by the name of the region or locality which identifies them, along with the trademark. | In addition to individualization issues of the IO, the only and unique characteristics of the region or locality gives the product requirements of typicality, characteristic or particular quality not found in others. This includes natural and human factors, such as history, savoir-faire and traditional production methods. There is standard of production and control. | |

| Applicability | Products and/or services | Products | |

| Characteristic | Informative (Refers to the territory or place from which the product derives) | Informative e Qualitative (Also denotes the characteristics resulting beyond the territory or place from which the product derives) | |

The two protection modalities may have their differences marked by different discussion trajectories and regulation. While the appellations of origin were firstly coined in the Lisbon Agreement, the indications of origin come from the Madrid Agreement5 (witch also approaches trademarks). The Agreement of Madrid aims mainly at suppressing false indications of origin of goods, whereas the Treaty of Lisbon focuses on denominations such as localities denominations used to designate products from where they originated and whose quality or characteristics are due exclusively or essentially to the geographical environment in which they are inserted (including natural and human factors) (WIPO, n.d.).

Several work groups within WIPO are aimed to discuss the updating of these legal landmarks. It is noteworthy that in May 2015 an international diplomatic conference which led to the adoption of a new record (Geneva Act) of the Lisbon Agreement was held. These minutes authorizes the international registration of geographical indications and allows the adhesion of certain intergovernmental organizations to the Lisbon Agreement (WIPO, 2015).

According to several authors [such as Gonçalves (2008), Trentini (2012), Varella (2005), among other Law scholars], both legal devices generate advantages (to a greater or lesser extent) to the holders of the right. The effects of law arising from the grant of GIs registration, according to Gonçalves (2008, p. 216), are:

- a)

the exclusive use of the recognized geographical name for goods or services designed on the record;

- b)

the right to have a geographical name recognized regardless of the product or service, but in what concerns the same for advertising or marketing purposes;

- c)

The use of expressions: geographical indication, indication of origin or appellation of origin; identifying its products or services listed in the registration, along with the brand;

- d)

The right to make use of legal means to prevent third parties from employing them as a distinctive sign, or other type of sign, identical or similar to the recognized geographical name.

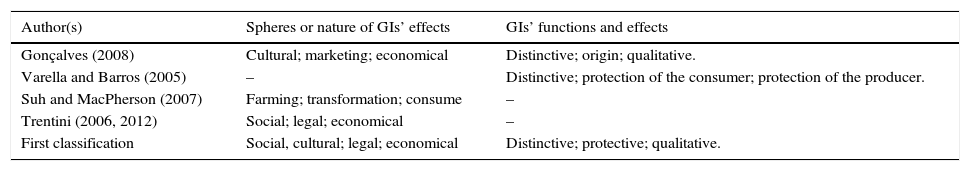

Gonçalves (2008) shows that, due to the above-mentioned rights, GIs have three functions (origin, distinctive and qualitative) and three aspects (cultural, economic and marketing). The origin function refers to the identification of the origin where the products are extracted, and is based on the principle of accuracy; the distinctive function refers to the fact that the geographical name differentiates the product/service of others available on the market; qualitative function, attributed to the geographical name, refers to the unique quality (typical) given because subjective and objective criteria and based on the existence of production and control standards. The cultural aspect refers to the fact that GIs establish the traditional cultural knowledge, to the old production practices repeated and transmitted from generation to generation; the advertising aspect refers to the fact that the distinctive sign can be used to “promote the sale of the product, attracting new customers and helping to conserve the existing ones” (Gonçalves, 2008, p. 68); and finally, the economic aspect refers to the value that satisfies the differentiation role in the market and the reflection of that in the economy and growth of the designated location.

Similarly to Gonçalves (2008), Suh and MacPherson (2007), Trentini (2006, 2012) and Varella and Barros (2005) also divide the functions of the indications in three distinct proposals. Varella and Barros (2005) focus on those involved in proposing that the three objectives are: product distinction (of its originality, typicality and quality); producer protection (maintaining its mode of production and by ensuring that the product is distinguished from others); and protection of consumers (which grants they are buying a well-known product). Suh and MacPherson (2007) approaches the impact of a GI in terms of sectors: primary sector (farming), secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (consumption of the product and by-products mainly due to the increase in tourism). Trentini (2006, 2012), in turn, seems to highlight the nature of the effects. By dealing more specifically with the origin, the author separates the functions in the categories: economic, legal and social.

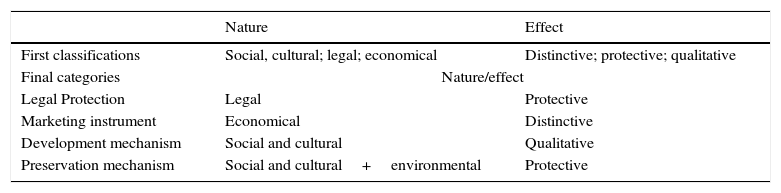

Given this framework, it is important to verify if the studies published show the same aspects or whether there are other indications and/or even more detail of what is included in each of these issues. Table 2 summarizes the issues raised by the authors and the initial classification used in this study.

Conceptual framework regarding the nature and functions of geographical indications.

| Author(s) | Spheres or nature of GIs’ effects | GIs’ functions and effects |

|---|---|---|

| Gonçalves (2008) | Cultural; marketing; economical | Distinctive; origin; qualitative. |

| Varella and Barros (2005) | – | Distinctive; protection of the consumer; protection of the producer. |

| Suh and MacPherson (2007) | Farming; transformation; consume | – |

| Trentini (2006, 2012) | Social; legal; economical | – |

| First classification | Social, cultural; legal; economical | Distinctive; protective; qualitative. |

After the systematic exposition of an integrative review, the analysis results are shown based on this first classification as described in the following section.

Methodological aspectsThe research is a systematized and integrative study aimed to analyze the functions and impacts of geographical indications described in Brazilian studies. This choice is based on the fact that the legislation of Brazil has some differences from other countries (as noted in the previous section), besides featuring a particular environment. The integrative review, in addition to showing an analysis of the knowledge produced, allows the generation of new knowledge through the integration of concepts, opinions and ideas systematically and critically analyzed (Botelho, Cunha, & Macedo, 2011; Mendes, Silveira, & Galvão, 2008).

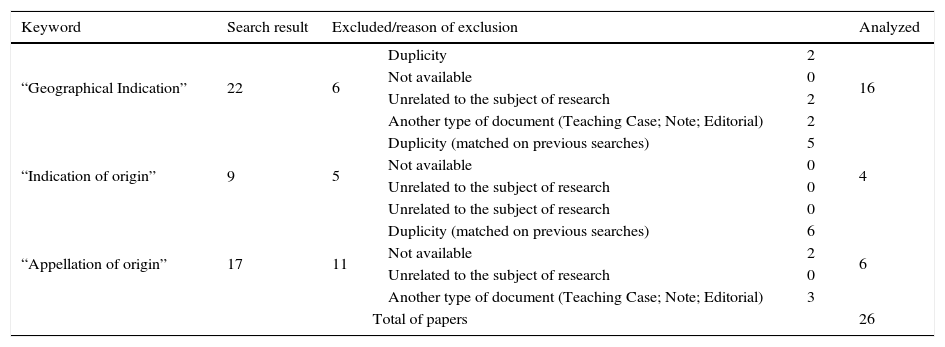

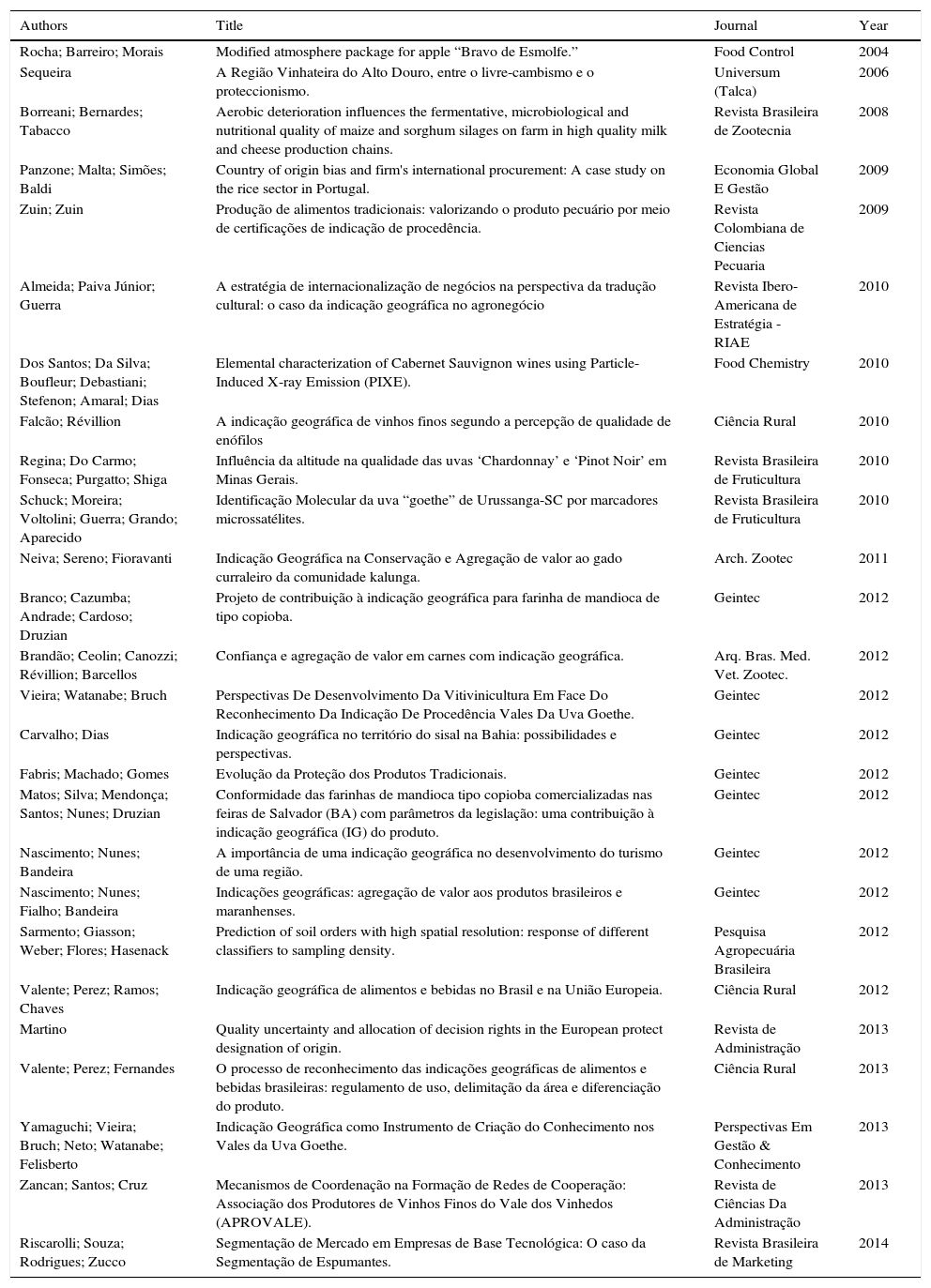

This comprehensive review was based on CAPES’ journals database with no restriction of publication period, area or academic ranking classification, and included 26 articles compiled from searches with the keywords “indication geographical”; “indication of origin” and “appellation of origin”. First, the search word was inserted, and the filter “papers” was applied. However, the filter did not prevent the system from returning some documents that cannot be characterized as this kind of item, and these were excluded. Next, a skimming was made, and it was verified that some works were not related to the subject in focus, but dealt with other issues such as geo-referencing or computer systems that approached geographic data and others. These works were ignored, as well as some works that were listed in more than one search. Thus, 22 out of 48 files were disconsidered. In the search results table, the reference terms are listed in the order they were matched in the systems (Table 3).

Result of the search in CAPES’ journals database.

| Keyword | Search result | Excluded/reason of exclusion | Analyzed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Geographical Indication” | 22 | 6 | Duplicity | 2 | 16 |

| Not available | 0 | ||||

| Unrelated to the subject of research | 2 | ||||

| Another type of document (Teaching Case; Note; Editorial) | 2 | ||||

| “Indication of origin” | 9 | 5 | Duplicity (matched on previous searches) | 5 | 4 |

| Not available | 0 | ||||

| Unrelated to the subject of research | 0 | ||||

| Unrelated to the subject of research | 0 | ||||

| “Appellation of origin” | 17 | 11 | Duplicity (matched on previous searches) | 6 | 6 |

| Not available | 2 | ||||

| Unrelated to the subject of research | 0 | ||||

| Another type of document (Teaching Case; Note; Editorial) | 3 | ||||

| Total of papers | 26 | ||||

The other 26 works (Appendix A) were integrally read. The searches were conducted from May 2014 to January 2015. There was no filter for the publication date, therefore any studies that met the criteria, apart from its novelty, were included. The first paper found, however, is dated from 2004, which highlights the recent academic production regarding the subject in the country.

Those issues were analyzed and grouped into categories by using content analysis because it is a set of methodological tools that apply to extremely diverse speeches (content and continents) (Bardin, 1977). According to Cooper and Schindler (2003, p. 347), the content analysis follows “a systematic process, starting with the selection of a unification scheme.” The first unification scheme proposed was the use of categories created a priori, developed based on literature review (Table 2). Based on the analysis of papers, categories were also created a posteriori, allowing greater detail of the initial categorization and agglutination of nature and effects as listed in the synthesis of Table 4.

Final scheme of the classification resulting from the analysis.

| Nature | Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| First classifications | Social, cultural; legal; economical | Distinctive; protective; qualitative |

| Final categories | Nature/effect | |

| Legal Protection | Legal | Protective |

| Marketing instrument | Economical | Distinctive |

| Development mechanism | Social and cultural | Qualitative |

| Preservation mechanism | Social and cultural+environmental | Protective |

The impacts attributed to the geographical indications mentioned by the authors were clumped together in summary tables within each function group (final categories). In order to develop these groups, it was necessary to understand the conjunction nature/effect and the frame of each impact mentioned by the authors. The following section includes this discussion and synthesis, and also the quantification of papers mentioning each issue. The quantification is a useful technique when pointing out the main factors of impacts. However, some authors may have privileged the exposure of the relevant impacts on the scope of the search, yet glimpsing other attributions.

Analysis and discussionThe compilation of the authors’ knowledge of the texts included in this comprehensive review enabled the composition of four function groups of GIs: legal protection instrument, marketing instrument, development mechanism and preservation mechanism. For each of the major groups, it was elaborated a summarizing table which contains the impacts attributed to the GIs inherent to the group, the authors of the papers that point each impact, the corresponding number of papers, and the approximate percentage that this number of papers represents within the sample. Each block is briefly described and discussed based on the review's authors that point out the relevant effects to these categories. The presentation of the results of this systematic review does not follow a particular order or relevance of the references, but one linkage in order to provide the best understanding.

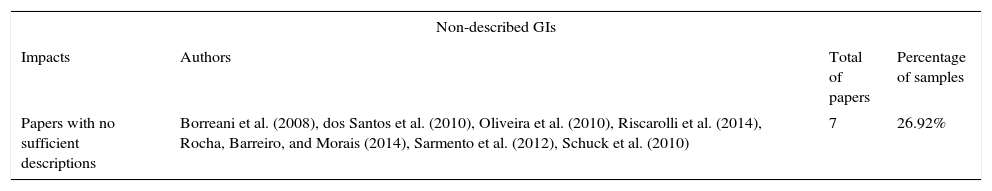

Not every work presents a description of the geographical indications or its functions and impacts (seven of them), and only explicit references were inserted. Thus, more detailing works tend to appear more often than those which present brief descriptions. In addition, there are cases where the geographical indication appeared as a secondary objective, relevance or consequence of the studies and there was no description of the concept or its implications, so it is not possible to make their categorization. These papers are described in Table 5 in order to make explicit all the studies analyzed in this systematic review.

Summary of the systematic review as for the implications of geographical indications – not described GIs.

| Non-described GIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts | Authors | Total of papers | Percentage of samples |

| Papers with no sufficient descriptions | Borreani et al. (2008), dos Santos et al. (2010), Oliveira et al. (2010), Riscarolli et al. (2014), Rocha, Barreiro, and Morais (2014), Sarmento et al. (2012), Schuck et al. (2010) | 7 | 26.92% |

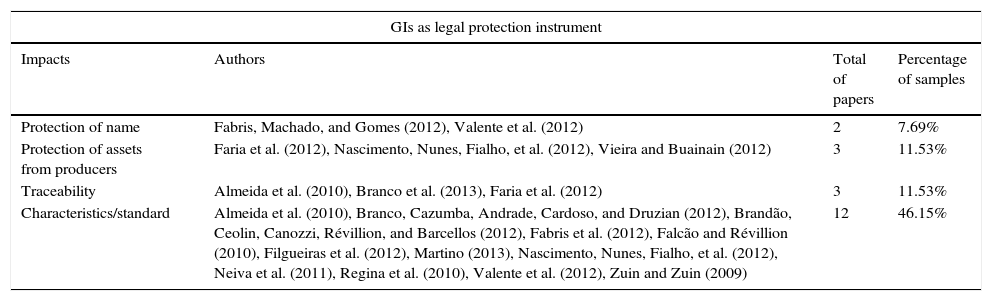

The major question when dealing with geographical indications is that these are legal instruments for protection of industrial property, however, they are not seen only from the perspective of the GI's holder, but also of the consumer, as shown in Table 6. The amount of protected actors was identified in the functions described by Varella and Barros (2005). In all cases, the nature of the protection can be considered legal because even if they indirectly imply health and information aspects, for instance, these aspects are inherent to the consumer's right (BRASIL, 1990).

Summary of the systematic review as for the implications of geographical indications – function: legal protection instrument.

| GIs as legal protection instrument | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts | Authors | Total of papers | Percentage of samples |

| Protection of name | Fabris, Machado, and Gomes (2012), Valente et al. (2012) | 2 | 7.69% |

| Protection of assets from producers | Faria et al. (2012), Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, et al. (2012), Vieira and Buainain (2012) | 3 | 11.53% |

| Traceability | Almeida et al. (2010), Branco et al. (2013), Faria et al. (2012) | 3 | 11.53% |

| Characteristics/standard | Almeida et al. (2010), Branco, Cazumba, Andrade, Cardoso, and Druzian (2012), Brandão, Ceolin, Canozzi, Révillion, and Barcellos (2012), Fabris et al. (2012), Falcão and Révillion (2010), Filgueiras et al. (2012), Martino (2013), Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, et al. (2012), Neiva et al. (2011), Regina et al. (2010), Valente et al. (2012), Zuin and Zuin (2009) | 12 | 46.15% |

As instruments of legal protection, the GIs are characterized as legal protection for consumers and producers. For producers, because they protect the use of their nominal identification and intangible assets, since the major objective of a GI is the protection of products and their geographical name (Valente, Perez, Ramos, & Chaves, 2012). In this sense, they can contribute to the fight against biopiracy and commercial fraud and forgery (Sautier, Biénabe, & Cerdan, 2011). And for consumers, because they ensure traceability (to the extent that the source is emphasized by the GI) and compliance with an established characterization.

The definition and maintenance of a standard can be a concern to those involved, and it is a challenge for the management (Allaire, Casabianca, & Thévenod-Mottet, 2011). The establishment of a standard can also be related to sustainability over time to establish productivity limits and avoid the overloading of the regional biological systems. This kind of choice also impacts the quality of the final product and in maintaining a good public image of these products. These factors also mean the possibility of getting a premium price (Lambert-Derkimba, Minéry, Barbat, Casabianca, & Verrier, 2010).

Generally, the standard to be maintained derives from conventions socially and historically built (traditions) as well as physical, chemical and taste characteristics observed in the products of certain regions. Some academic studies have sought to provide basis regarding the identification and definition of these standards to obtain the record, mainly for the appellations of origin, but also for indications of origin6 (dos Santos et al., 2010; Filgueiras et al., 2012; Mattos, 2011; Regina, Do Carmo, Fonseca, Purgatto, & Shiga, 2010; Sarmento, Giasson, Weber, Flores, & Hasenack, 2012; Schuck et al., 2010). There are those who debate intervening factors that may impact the previously defined characteristics, such as the impact of the type of pasture management on the quality of milk to produce some cheese that holds an AO (Borreani, Bernardes, & Tabacco, 2008).

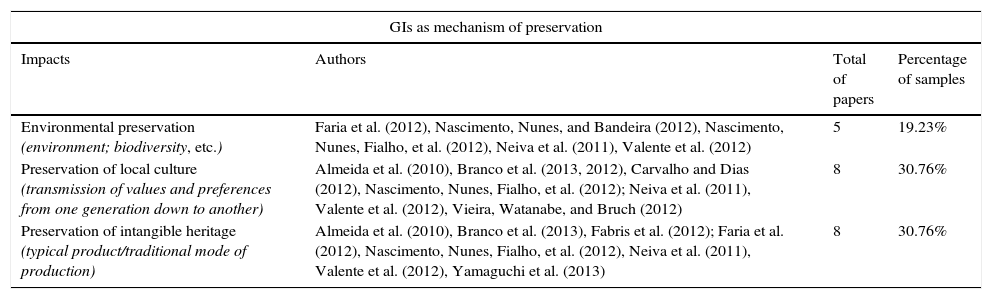

According to the authors listed in Table 7, geographical indications are seen as instruments able to assist the preservation of traditions, savoir-faire (intangible heritage) and environment. It is related to the maintenance of the characteristics that originate from the renowned geographical indications, as well as the preservation of the remaining assets of the producers.

Summary of the systematic review as for the implications of geographical indications – function: preservation mechanism.

| GIs as mechanism of preservation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts | Authors | Total of papers | Percentage of samples |

| Environmental preservation (environment; biodiversity, etc.) | Faria et al. (2012), Nascimento, Nunes, and Bandeira (2012), Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, et al. (2012), Neiva et al. (2011), Valente et al. (2012) | 5 | 19.23% |

| Preservation of local culture (transmission of values and preferences from one generation down to another) | Almeida et al. (2010), Branco et al. (2013, 2012), Carvalho and Dias (2012), Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, et al. (2012); Neiva et al. (2011), Valente et al. (2012), Vieira, Watanabe, and Bruch (2012) | 8 | 30.76% |

| Preservation of intangible heritage (typical product/traditional mode of production) | Almeida et al. (2010), Branco et al. (2013), Fabris et al. (2012); Faria et al. (2012), Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, et al. (2012), Neiva et al. (2011), Valente et al. (2012), Yamaguchi et al. (2013) | 8 | 30.76% |

The most referenced issue (Table 7) was the preservation of intangible heritage and appreciation of culture, although environmental conservation also is referenced. Among scholars that referenced the issue of preservation, there was no mention that the geographical indication acted as a stimulus for the preservation of material heritage (such as architectural ensemble, production sites, or collection of property with artifacts used in production over time). But perhaps this issue is inserted into the development of tourism (impact shown in Table 8) because, in some cases, tourists want to know the locations of production and are interested in the assets related to the holder of the GI, as verified by Medeiros (2015) regarding the indication of origin of the artisanal cheese from Serro.

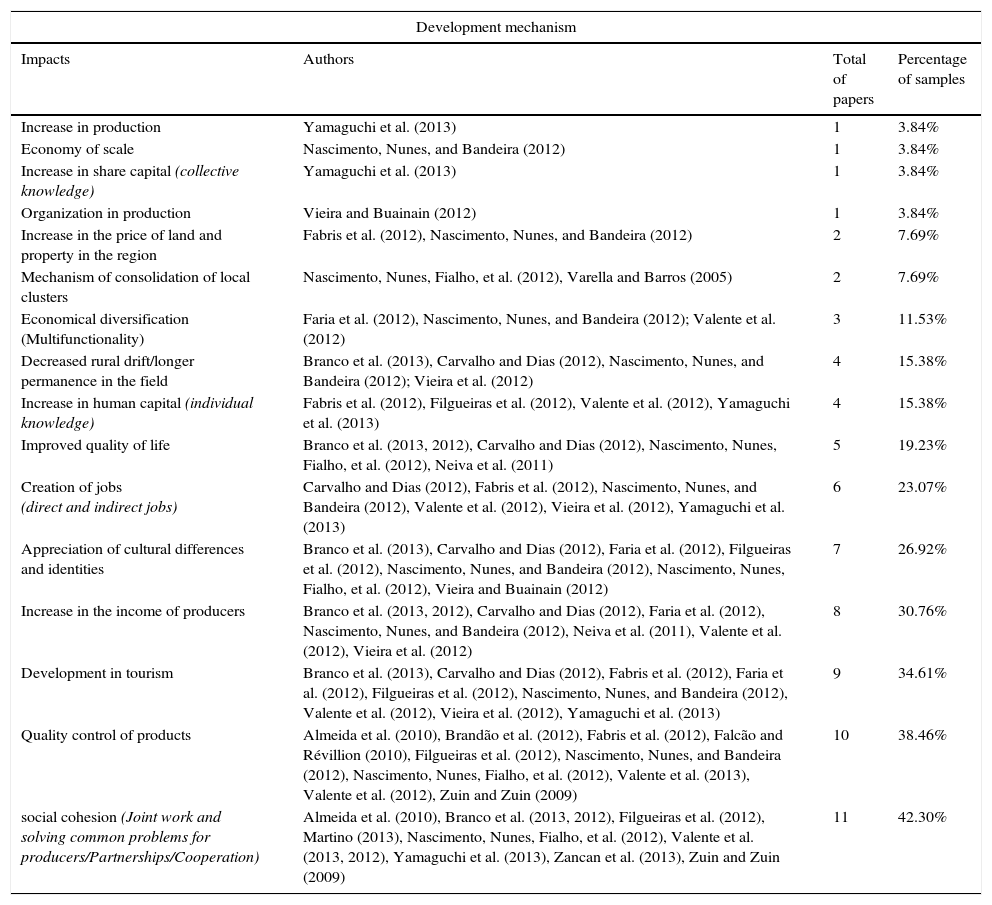

Summary of the systematic review as for the implications of geographical indications – function: development mechanism.

There is questioning whether the use of geographical indications constitutes a tool for rural development and for commercial return (Sautier et al., 2011), and many effects were referenced in both categories. Table 8 shows the references classified as Rural Development Mechanism, and Table 9 as marketing tool.

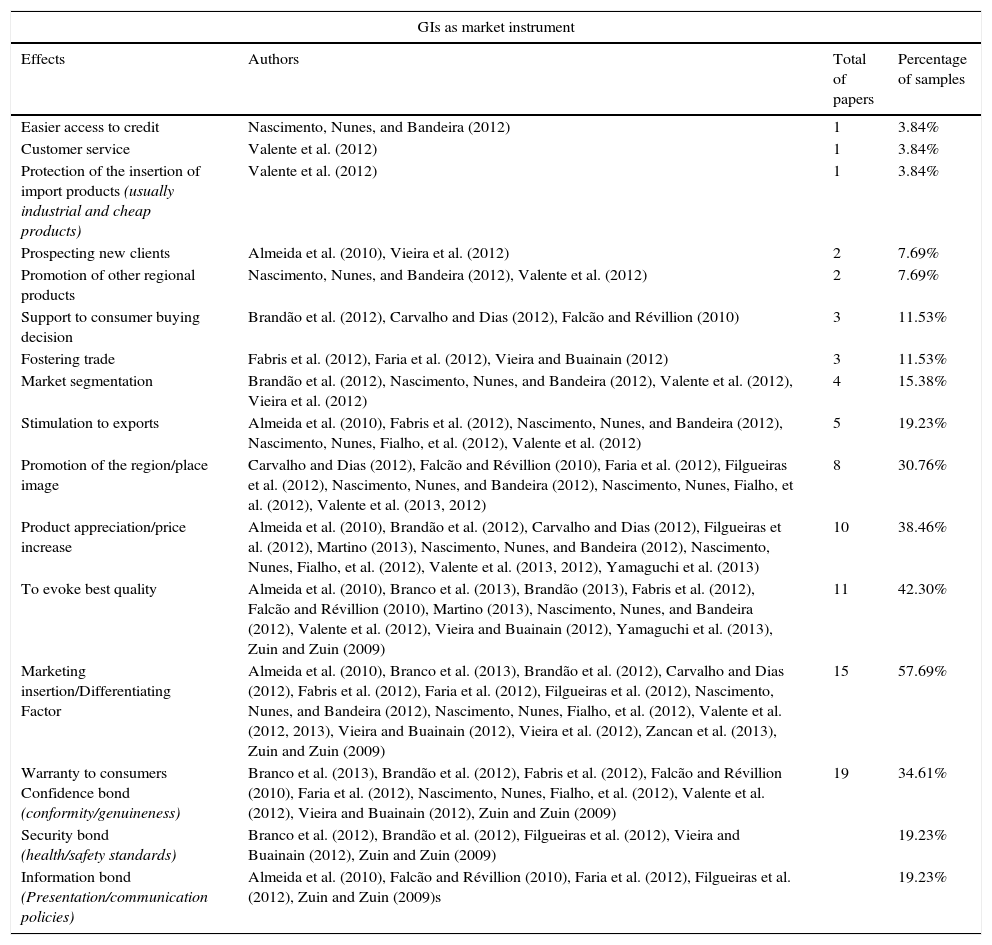

Summary of the systematic review as for the implications of geographical indications – market instrument.

According to Trentini (2006), the idea of quality is inaccurate, subjective and changeable according to the change of time and places. Therefore, geographical indications could evoke specific characteristics linked to a territory, but not designate a high level of quality (Allaire et al., 2011; Trentini, 2006). However, as stated by other authors in this section, this tendency is innate to an economic necessity and to a subjective conception of consumers.

At first, the register of geographical indications was a commercial practice and it is still so (Barjolle et al., 2011; Sautier et al., 2011), however, although they have not been designed for rural development purposes or preservation the cultural and natural heritage, they can become instruments also for this purpose (Sautier et al., 2011). Geographical indications have a cultural dimension since the product characteristics and the manner they are produced, stored, marketed and even consumed are innate in the local community (Belletti & Marescotti, 2011). According to some authors (Belletti & Marescotti, 2011; Sautier et al., 2011), culture is a heritage, and communities should have the right to use it for economic, social and cultural gains. Moreover, registration of geographical indications requires financial investment by the community; therefore, the strategy needs to be profitable to its participants.

The production systems of geographical indications can provide sustainability for rural development: economic sustainability (strengthening the local supply chain and opportunities for diversification and integration of the economic activities in rural areas), social sustainability (cohesion of local actors, empowerment, inclusion, etc.) and environmental sustainability (biodiversity, landscape, land use, etc.) (Belletti & Marescotti, 2011). Regarding economic issues, in general, the authors point out the development of tourism, hospitality, catering, craft and other services as a way of multi-functionality (Branco et al., 2013; Medeiros & Passador, 2015). In what concerns the social aspects, work and collective decisions are highlighted, as well as the establishment and institutionalization of partnerships and the increase of human capital with higher qualifications and demand for expertise (Filgueiras et al., 2012; Zuin & Zuin, 2009). Finally, the environmental aspects are maintained and better used as a basic condition for the existence of geographical features that allowed the registration of geographical indication (Nascimento, Nunes, & Bandeira, 2012; Neiva, Sereno, & Fioravanti, 2011).

In this manner, the exploitation of geographical indications as a means of making economic gains cannot be considered the opposite or not identical to the conception guided in rural development, but as a complement to this. The conception of the development mechanism was separated from the marketing, although they are complementary to each other, due to the approach used in the references made by the authors. In Table 9 the emphasis is in the use of geographical indications given in business development and assessment of higher profits, whereas Table 8 emphases the support to the local community. This design involves economic factors, but also includes social issues. One cannot deny the complementarity of the GI vision as a factor of rural development with the preservation issues mentioned in Table 7, and in order to raise the possibility of future use of the asset, it is necessary to have the maintenance of resources and conditions that allow it.

Geographical indications can generate satisfied producers due to the appreciation of their products and way of life, and also foster the pride and sense of belonging (Nascimento, Nunes, & Bandeira, 2012). This particular identity can be appropriate and strengthened in the development of tourist activities associated with rural areas and with the product (Medeiros & Passador, 2015; Nascimento, Nunes, & Bandeira, 2012).

The registered product is also emphasized, as well as products related to it and the producing region itself. In general, the issues are mentioned both as cause and as result, in an apparent shaping cycle of a positive process of regional development. The joints are seen as essential for the possible articulation of sectors, economies of scale, knowledge transfer, creating innovations and the consolidation and strengthening of productive arrangements in the context of a GI. The existence of some coordination mechanisms with the existence of key actors/leaders was highlighted as important for the formation of these networks for both inter-organizational relationships (Zancan, Santos, & Cruz, 2013).

The great importance given to the market may be inherent in the design of the protective instrument. This may have contributed to the long list of impacts with this bias mentioned in the studies analyzed (Table 9).

As a marketing instrument (Table 9), GIs are understood as: (a) a manner to improve, by their use or marketing, the terms of trade over time (of the product protected by the indication, other products or the region); (b) an instrument to stimulate commerce by delivering products, credit and handling of debts, and (c) a manner to influence consumer behavior. In the latter sense, it is a support to decision-making and influences the perception (before and after consumption).

As several dimensions of quality (of food products’, especially) cannot be identified prior to purchase, consumers form expectations based on their individual perceptions (Falcão & Révillion, 2010). Tregear and Giraud (2011) state that indications can reduce the asymmetry of information between buyers and sellers, thus facilitating and accelerating their decision-making. This comes from the fact that IGs act as “informational shortcuts”, “access to attributes”, guarantee of authenticity, safety and expansion of the quality perception (Brandão, Ceolin, Canozzi, Révillion, & Barcellos, 2012; Falcão & Révillion, 2010; Tregear & Giraud, 2011). Moreover, decisions regarding food consumption are often non-rational, affective or emotional, and the “special” nature of GIs corroborate with this choice. GIs incorporate the symbolic capital and its potential to evoke deep feelings in consumers such as identity, heritage, pride, belonging, dreams and even fantasies (Tregear & Giraud, 2011). Some works that mention the issues of conformity/genuineness, safety and health security, and information (Table 9). Although these issues are discussed, or the advantages given to consumers, who now have an extra security at the time of decision and of consume of products with a geographical indication, or as a marketing opportunity (in the specific case of the communication issue), these issues may be considered inherent in the basic consumer rights. In Article 6 of the Consumer Protection Code (BRASIL, 1990) provides those rights, including the protection of health and safety, the access to clear information, protection against misleading advertising, among other issues. Articles 9 and 10 emphasize the responsibility assumed by the supplier in what concerns health and security, and GIs would be able to support the consumer to have their rights guaranteed, thus acting as an indicator of the perception of those terms that every supplier of product or service is obliged to meet.

The integrated communication applied to registered products may not only inform, but also attract consumers (Falcão & Révillion, 2010; Tregear & Giraud, 2011; Tregear, Kuznesof, & Moxey, 1999). The communication process involves the credibility of the source, the consumer perception ability and, in the case of a product with GI, it may be necessary to carry out research to check the factors perceived by consumers and/or those to be highlighted (Falcão & Révillion, 2010). It is also worth mentioning that the geographical indication registration is not equivalent nor excludes the use of trademarks.7 Certification, collective, and individual marks can coexist with the geographical indication registration and can be disclosed on labels, packaging and other types of media. The same organization can have an individual mark and make use of geographical indications and collective and/or sector marks in order to improve their strategies and position their product on the market (Castro & Giraldi, 2015).

Involving communication, but not restricted to it, there is the process of strategic planning and marketing management that applies not only to the registered product but also to related products and the territory that produces it. Geographical indication may facilitate the marketing of the territory to provide greater visibility of the place (Carvalho & Dias, 2012). Issues such as segmentation, choice of target market, uniqueness and the establishment of a correct marketing mix are also debated (Almeida, Paiva Júnior, & Guerra, 2010; Branco et al., 2013; Brandão et al., 2012; Nascimento, Nunes, Fialho, & Bandeira, 2012; Oliveira, Rubin, & Nunes, 2010).

Approaching these issues requires analysis and definition of strategies so the consumer decides favorably to the product. The better the combination of product characteristics (price, place of distribution, communication, packaging, size, etc.) and the interest segments, the more likely it is to happen (Riscarolli, Souza, Rodrigues, & Zucco, 2014).

According to Brandão et al. (2012), the increased demand for food products with a geographical indication has occurred to meet specific market niches. Uniqueness and the consequent enhancement of the product are also emphasized. Gonçalves (2008, p. 42) points out the issue's relevance within the agribusiness context to explain that there may be a difference between market commodities and market specialties, where there is more added value to the product.

Therefore, product becomes a unique article. Uniqueness, coupled with a perception of higher quality, tends to make the highest monetary value and consequently raises the income of producers (Mendes & Antoniazzi, 2012). The authors state that GIs can facilitate the insertion of small and medium producers, since this uniqueness can raise competition with large producers. Moreover, geographical indication can facilitate the presence of products in the market, allow the charging of higher prices, and promote the stability of demand (Valente et al., 2012).

In addition to marketing perspective, there is a strong idea of product protection and how to apply it. Varella and Barros (2005) observe the perspective of social articulation since it is required collective and often volunteer action to raise the awareness, proposals, implementation and protection of geographical indications. Collective mobilization around the GIs has also been seen as a means to strengthen the supply chain for the benefit of producers and consumers because they can reduce the strength of off-takers and enable to be familiar with all the parties involved from production to consumption (Branco et al., 2013; Varella & Barros, 2005).

Martino (2013) emphasizes the governance and decision-making as subjects to be analyzed in the context of geographical indications. According to the author, the allocation of decision derives from individuals to collective organizations, and it depends on the context of existing control structures and on the degree of formalization, design and implementation of monitoring and control systems, and inter-institutional cooperation.

It is also referenced that the impact of geographical indications depends on the recognition of the specificity of the products, which leads to a better market positioning; and collective mobilization that is needed to define and implement the geographical indications (Réviron & Chappuis, 2011). Therefore, categories cannot be considered when isolated, but as interacting and interdependent elements. Moreover, the simple approval of a GI does not guarantee collective development, for there must be a correlation of favorable forces between the actors, including the State, which evidences and foster the social skills of a community, otherwise, GI may become an instrument of exclusion and inequality among members of the value chain (Valente et al., 2012). Not only protagonism should be encouraged, but the awareness of long-term development and return must be built, so that the GI recognition process is orderly and consistently carried out, focused on future results, and not immediate results, at the risk of frustrating the actors involved (Valente et al., 2012, p. 557).

Although there are several positive impacts, some producers could be dishonest when misleadingly or illegally conducting some activities with the use of geographical indications. The restriction on free trade of products and goods due to the monopoly of a “name” or privilege of some products, as well as unfair trade practices (overpricing, cartel8 and e dumping,9 for instance) (Trentini, 2012). These practices and misuses should be observed by the various stakeholders and especially by the producers who hold geographical indications (Varella & Barros, 2005). It should also be noted that the exceptions mentioned do not refer to normal functioning of the registry, but to its misuse. Moreover, these practices are restrained by the Brazilian system of repression of unfair competition (which immediately protects the entrepreneur) and the antitrust law (which protects the market) (Trentini, 2012).

Final considerationsThe present paper aimed to analyze the functions and impacts attributed to geographical indications as referenced in papers available through the CAPES’ Journal database up to early 2015. It was found 26 works from different areas, and the first one was dated in 2004 (two years after the first Brazilian geographical indication registration). According to these studies, geographical indications can be considered a strategy since they can meet different purposes and involve different actors. They can be protection instruments (to consumer and farmer); marketing instrument (emphasizing the uniqueness of a product or service); rural development mechanism (as it can impact the generation and maintenance of employment, income distribution, local identity, etc.); and means of preservation (traditions, savoir-faire and even ingredients).

The articles analyzed showed different impacts (33) which could be classified within those functions. Inside the function “protection”, the referenced issue was the establishment and/or maintenance of typicality/standard (46.1% of the 26 articles). In “preservation”, there was equal number of references (eight papers, 30.7% out of the total) to the conservation of culture and intangible heritage. In “development”, the most referenced impact was social cohesion (42.3%). Finally, in “marketing”, the implications in highlight were uniqueness (57.6%) and evoked quality (42.3%). In this manner, the most referenced issue is market, which is consistent with the conception of the GIs as a tool of intellectual property.

Although considered positive impacts, the issues herein are characterized as challenges to managers of rural proprieties, to organizations responsible for the registration of any GI, and to public managers because management problems of production, equity, human resources, and marketing, among others, are not unusual. Several other positive aspects were highlighted, and it was also mentioned that the registry itself does not guarantee the achievement of such benefits. Therefore, one of the questions that can be singled out as a topic to be investigated is how to carry out these functions and effects or even how to face the management challenges innate to the desired impacts. One of the best ways to understand it could be through the study of the actions and relationships in cases of success and failure. The categories set out in this work, as well as its sub-categories, can be used in this type of study.

A few works that distinguish the implications of geographical indications according to their type (IO or AO). Perhaps those studies in places where products obtained indication of origin and then appellation of origin may help elucidate whether there are differences and what they are. Bridging this gap could contribute to future requests, and requesters can have a guide to which type of GI to request according to their intended purposes to prevent making two requests, like in some Brazilian cases. They can also give support to works that shed light on specific aspects checking for reflections arising from registered GIs, as developed by Yamaguchi et al. (2013) with respect to how the origin of information may contribute to the creation of knowledge.

Theoretically, there is no better or worse distinction among types, but there is difference among registers (notoriety in the case of IOs and quality bond in the case of AOs), however, there was a study that mentioned that the region was looking for “higher category”. Another gap pointed out in this comprehensive review refers to clarify the difference between various terms used to refer to geographical indications as well as the correct description of their categories.

In the common usage, it is recurrent the use of terms as synonyms of registers of geographical indication although they are not actually equivalent. This also occurred in seven (27%) academic papers analyzed, which met the misuse of the terms such as “label of origin,” “mark of origin”, “geographical indication mark”, “stamp of origin” and “geographical indication of controlled origin”. There were also cases where the use of terms was not incorrect as a synonym, but perhaps could induce the reader to confuse the words: “under the designation of origin label” and “stamp of communication with the market”. Very few papers reference the difference of IO and AO concepts (Valente, Perez, & Fernandes, 2013; Yamaguchi et al., 2013). These misconceptions can be considered limitations to this study, as they may imply in assignment of roles and impacts to GIs that refer to other “seals”. Thus, it is clear that the lack of clarity with respect to the specific sign permeates the academic field, and is necessary, as well as more applied research, the improvement of scientific communication on GI to the society and with the society.

Finally, most of the works comes from previous analyzes of the geographical indication registration process (9 papers), the description of the process itself (4) or the discussion of the potential relating to them (6). So it is emphasized the need for a post-analysis of the process that include results and consumer perception (3), but also of the producers, the impact on other sectors, system organization, description of successful and unsuccessful actions. Besides, a comprehensive review contemplating theses and dissertations on geographical indications already concluded in Brazil is suggested; as well as bibliometric work, and specific or compared case studies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of the papers analyzed in this comprehensive review.

| Authors | Title | Journal | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rocha; Barreiro; Morais | Modified atmosphere package for apple “Bravo de Esmolfe.” | Food Control | 2004 |

| Sequeira | A Região Vinhateira do Alto Douro, entre o livre-cambismo e o proteccionismo. | Universum (Talca) | 2006 |

| Borreani; Bernardes; Tabacco | Aerobic deterioration influences the fermentative, microbiological and nutritional quality of maize and sorghum silages on farm in high quality milk and cheese production chains. | Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia | 2008 |

| Panzone; Malta; Simões; Baldi | Country of origin bias and firm's international procurement: A case study on the rice sector in Portugal. | Economia Global E Gestão | 2009 |

| Zuin; Zuin | Produção de alimentos tradicionais: valorizando o produto pecuário por meio de certificações de indicação de procedência. | Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuaria | 2009 |

| Almeida; Paiva Júnior; Guerra | A estratégia de internacionalização de negócios na perspectiva da tradução cultural: o caso da indicação geográfica no agronegócio | Revista Ibero-Americana de Estratégia - RIAE | 2010 |

| Dos Santos; Da Silva; Boufleur; Debastiani; Stefenon; Amaral; Dias | Elemental characterization of Cabernet Sauvignon wines using Particle-Induced X-ray Emission (PIXE). | Food Chemistry | 2010 |

| Falcão; Révillion | A indicação geográfica de vinhos finos segundo a percepção de qualidade de enófilos | Ciência Rural | 2010 |

| Regina; Do Carmo; Fonseca; Purgatto; Shiga | Influência da altitude na qualidade das uvas ‘Chardonnay’ e ‘Pinot Noir’ em Minas Gerais. | Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura | 2010 |

| Schuck; Moreira; Voltolini; Guerra; Grando; Aparecido | Identificação Molecular da uva “goethe” de Urussanga-SC por marcadores microssatélites. | Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura | 2010 |

| Neiva; Sereno; Fioravanti | Indicação Geográfica na Conservação e Agregação de valor ao gado curraleiro da comunidade kalunga. | Arch. Zootec | 2011 |

| Branco; Cazumba; Andrade; Cardoso; Druzian | Projeto de contribuição à indicação geográfica para farinha de mandioca de tipo copioba. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Brandão; Ceolin; Canozzi; Révillion; Barcellos | Confiança e agregação de valor em carnes com indicação geográfica. | Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. | 2012 |

| Vieira; Watanabe; Bruch | Perspectivas De Desenvolvimento Da Vitivinicultura Em Face Do Reconhecimento Da Indicação De Procedência Vales Da Uva Goethe. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Carvalho; Dias | Indicação geográfica no território do sisal na Bahia: possibilidades e perspectivas. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Fabris; Machado; Gomes | Evolução da Proteção dos Produtos Tradicionais. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Matos; Silva; Mendonça; Santos; Nunes; Druzian | Conformidade das farinhas de mandioca tipo copioba comercializadas nas feiras de Salvador (BA) com parâmetros da legislação: uma contribuição à indicação geográfica (IG) do produto. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Nascimento; Nunes; Bandeira | A importância de uma indicação geográfica no desenvolvimento do turismo de uma região. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Nascimento; Nunes; Fialho; Bandeira | Indicações geográficas: agregação de valor aos produtos brasileiros e maranhenses. | Geintec | 2012 |

| Sarmento; Giasson; Weber; Flores; Hasenack | Prediction of soil orders with high spatial resolution: response of different classifiers to sampling density. | Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira | 2012 |

| Valente; Perez; Ramos; Chaves | Indicação geográfica de alimentos e bebidas no Brasil e na União Europeia. | Ciência Rural | 2012 |

| Martino | Quality uncertainty and allocation of decision rights in the European protect designation of origin. | Revista de Administração | 2013 |

| Valente; Perez; Fernandes | O processo de reconhecimento das indicações geográficas de alimentos e bebidas brasileiras: regulamento de uso, delimitação da área e diferenciação do produto. | Ciência Rural | 2013 |

| Yamaguchi; Vieira; Bruch; Neto; Watanabe; Felisberto | Indicação Geográfica como Instrumento de Criação do Conhecimento nos Vales da Uva Goethe. | Perspectivas Em Gestão & Conhecimento | 2013 |

| Zancan; Santos; Cruz | Mecanismos de Coordenação na Formação de Redes de Cooperação: Associação dos Produtores de Vinhos Finos do Vale dos Vinhedos (APROVALE). | Revista de Ciências Da Administração | 2013 |

| Riscarolli; Souza; Rodrigues; Zucco | Segmentação de Mercado em Empresas de Base Tecnológica: O caso da Segmentação de Espumantes. | Revista Brasileira de Marketing | 2014 |

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.

Barjolle, Sylvander, and Thévenod-Mottet (2011) also indicate that the "origin of products" are designated differently from country to country, and that terms carry different meanings regarding the possibility of use and values assigned to the factors of connection with the territory. The main legal definition internationally adopted are: appeal of origin, protected designation of origin, protected geographical indication, and geographical indication (Barham, 2003; Barham & Sylvander, 2011). In Brazil, GIs are applicable to goods and services, industrial and agricultural, while in European countries, for example, the law applies only to agricultural products, wines and spirits. For further studies, see Valente et al. (2012).

It should be mentioned that there are previous studies of international marketing regarding the effects of the origin of products and/or brands, but no records or certifications. Other ways to communicate information regarding the origin of the product such as “made in” label, the direct suggestion of the brand or company name, indirect suggestion by sound or spelling of the brand or organization name, or the suggestion of the packaging discussed for more than three hundred studies since 1965 (Giraldi & Carvalho, 2006).

According to a search on CAPES and Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations of the Brazilian Institute for Information in Science and Technology held in January 2015.

According to the third paragraph of Article 10a of the Paris Convention, confusing act is understood as any act capable of creating confusion, inducing the public to error regarding a competitor's business or shop, products, characteristics, quantities, possibilities of use, industrial or commercial activities, etc. (WIPO, 1975).

International treaties and agreements on intellectual property are the result of negotiations and consensus among countries in order to ensure the effectiveness of the international intellectual property system. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), which is a United Nations body, manages them. There are three main existing protection systems in this area: the Madrid System for trademarks; Hague System for industrial designs; and Lisbon System for the protection of appellations of origin.

The definition of standard and specific quality is linked to the AOs since their registration is required to prove the specificity of the product in relation to the territory. For the IO, registration is linked to notoriety, but still, characterization and establishment of use regulation is required.

Likely trademarks, geographical Indication, brand names and domain names, among others, are distinctive signs. These signs demonstrate in the market the differences in origin (commercial or geographical), in features or specific qualities. GIs refer to the distinction that is attributed essentially to the geographical origin (BRASIL, 1996). Mark refers to "every distinctive, visually perceptible sign that identifies and distinguishes products and services, as well as certifies their compliance with certain standards or technical specifications" (INPI, n.d.). There can be four types: product, service, collective or certification. Collective are intended to identify products or services of a collectivity represented by a legal entity (association, cooperative, union, consortium, etc.), so they can make use to those who are members of the entity that holds the collective mark fulfilling any conditions and criteria established by it. Certification marks attest conformity of a product or service under certain rules, standards or technical specifications, and used by a third party with the permission/certificate of conformity. In the case of geographical indication there is a delimitation of the area and product, and there is a use regulation. All those who produce the goods or services within the defined area and in accordance with the regulation may use the geographical indication. It should be noted that the regulation of use of a GI is not necessarily verified by a certifying entity, and the entity's responsibility is to establish collective forms to ensure compliance. (BRASIL, 1996; INPI, n.d.; Yamaguchi et al., 2013).

Cartel is an association of competing companies in search of profits higher than those obtained without this agreement. It usually involves price fixing or division of customers and production quotas.

Dumping is also a manner of eliminating competition, but in this case, instead of having the association with the competitor, there is the practice of lower prices in order to derail the competitor's operations.